Richard Wright (author) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Wright

|

|

|---|---|

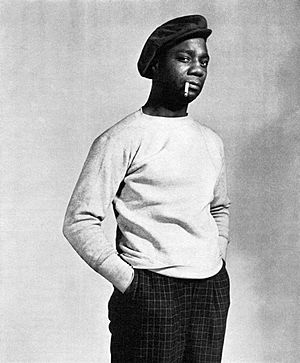

Wright in a 1939 photograph by Carl Van Vechten

|

|

| Born | Richard Nathaniel Wright September 4, 1908 Plantation, Roxie, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | November 28, 1960 (aged 52) Paris, France |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1938–60 |

| Genre | Drama, fiction, non-fiction, autobiography |

| Notable works | Uncle Tom's Children, Native Son, Black Boy, The Outsider |

| Spouses |

Dhimah Rose Meidman

(m. 1939; div. 1940)Ellen Poplar

(m. 1941) |

| Children | 2 |

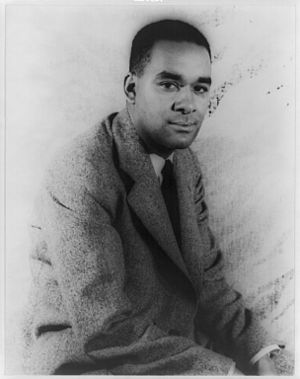

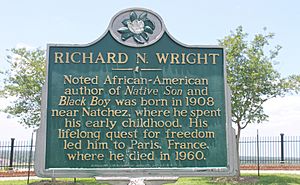

Richard Nathaniel Wright (born September 4, 1908 – died November 28, 1960) was an American writer. He wrote novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction books. Many of his stories focused on issues of race. He wrote about the struggles of African Americans from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. They faced unfair treatment and violence. Many experts believe his writing helped change how people thought about race in the United States.

Contents

Richard Wright's Early Life and School

Richard Wright wrote a book about his early life called Black Boy. It covers his life from 1912 to 1936. Richard was born on September 4, 1908. His birthplace was Rucker's Plantation in Mississippi. His father, Nathan Wright, was a sharecropper. His mother, Ella Wilson, was a schoolteacher. Both of his parents were born free after the Civil War. His grandparents had been enslaved and gained freedom from the war. Both grandfathers fought in the Civil War.

Richard's father left the family when Richard was six years old. He did not see his father again for 25 years. In 1911 or 1912, his mother moved them to Natchez, Mississippi. They lived with her parents there.

Richard went to Howe Institute in Memphis from 1915 to 1916. In 1916, his mother moved with Richard and his younger brother. They went to live with his aunt Maggie and her husband Silas in Elaine, Arkansas. This area was part of the Mississippi Delta, where cotton farms used to be.

After his mother had a stroke, Richard was separated from his brother. He lived briefly with his uncle and aunt in Greenwood, Mississippi. By age 12, he had not completed a full year of school. Soon, Richard, his brother, and mother returned to his grandmother's home. This home was in Jackson, Mississippi, the state capital. He lived there from 1920 to 1925. His grandparents were often angry with him. They beat Richard and his brother.

While living there, he finally attended school regularly. He went to a Seventh-day Adventist school from 1920 to 1921. His aunt Addie was his teacher. After a year, at age 13, he entered Jim Hill public school in 1921. He was promoted to sixth grade after only two weeks. Richard was unhappy in his grandparents' home. His aunt and grandmother tried to force him to pray. They wanted him to build a relationship with God. Wright later threatened to leave his grandmother's home. This was because she would not let him work on Saturday, the Adventist Sabbath. Their strict rules made him dislike religious teachings. This dislike appeared in his writings throughout his life.

At age 15, while in eighth grade, Wright published his first story. It was called "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre." It appeared in the local Black newspaper Southern Register. No copies of this story still exist. In his book Black Boy, he said the story was about a bad guy who wanted a widow's home.

In 1923, Richard did very well in school. He became the class valedictorian of Smith Robertson Junior High School. He graduated in May 1925. He was asked to write a speech for graduation. It was to be given in a public hall. Before graduation, the principal gave him a different speech to read. Richard told the principal that people came to hear the students' own words. He refused to read the principal's speech. The principal threatened him, saying he might not graduate. He also offered Richard a chance to become a teacher. Richard did not want to be called an Uncle Tom. He refused to give a speech written to please white school officials. He convinced everyone to let him read his own words.

In September 1925, Wright signed up for classes at the new Lanier High School. This school was built for Black students in Jackson. Schools were separated by race because of Jim Crow laws. But Richard had to stop attending classes after a few weeks. He needed to earn money to help his family.

In November 1925, at age 17, Wright moved to Memphis, Tennessee. There, he loved to read. He was so hungry for books that he found a clever way to borrow them. He used a library card from a white coworker. He wrote fake notes saying he was picking up books for the white man. This way, Wright could get and read books that were forbidden to Black people. This also gave him access to magazines like Harper's and Atlantic Monthly.

He planned for his mother to join him when he could support her. In 1926, his mother and younger brother moved to Memphis. Soon after, Richard decided to leave the Jim Crow South. He wanted to go to Chicago. His family joined the Great Migration. This was when many Black people left the South. They sought better opportunities in northern and mid-western cities.

Richard Wright's childhood in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas deeply shaped his views on racism in America.

Coming of Age in Chicago

Wright and his family moved to Chicago in 1927. He got a job as a postal clerk. He used his free time to study other writers. He was especially impressed by H. L. Mencken. Mencken saw the American South as a kind of Hell. When Wright lost his job during the Great Depression, he had to go on relief in 1931. In 1932, he started going to meetings of the John Reed Club. This was a literary group that followed Marxist ideas. Wright met and connected with members of the Communist Party. He formally joined the Communist Party and the John Reed Club in late 1933.

In 1933, Wright started the South Side Writers Group. Writers like Arna Bontemps and Margaret Walker were members. Through this group and the John Reed Club, Wright started and edited Left Front. This was a literary magazine. Wright began publishing his poems there in 1934. His first novel, Cesspool, was finished by 1935. Eight publishers rejected it. It was published after his death as Lawd Today (1963). This book was based on his own experiences working at a post office in Chicago.

In January 1936, his story "Big Boy Leaves Home" was accepted for publication. It appeared in the book New Caravan. It was also in the collection Uncle Tom's Children. These stories focused on Black life in the rural American South.

In February 1936, he started working with the National Negro Congress. He spoke at their Chicago meeting. He talked about "The Role of the Negro Artist and Writer in the Changing Social Order." He wanted to create publications, exhibits, and conferences. He also worked with the Federal Writers' Project to help Black artists find work.

In 1937, he became the Harlem editor for The Daily Worker. This job involved gathering quotes from interviews. This left him time for other projects. A year later, Uncle Tom's Children was published. Wright had good relationships with white Communists in Chicago. But he was later treated badly in New York City. Some white party members took back an offer to help him find housing when they learned he was Black. Some Black Communists called Wright a "bourgeois intellectual." Wright was mostly self-taught. He had to leave school after junior high to support his family.

During the Soviet agreement with Nazi Germany in 1940, Wright focused on racism in the United States. He eventually left the Communist Party. This was because they changed their stance against segregation and racism. They joined Stalinists in supporting the US entering World War II in 1941. Wright believed young communist writers should be free to develop their skills. He later wrote about this experience in his essay "I tried to be a Communist." It was published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1944. This essay was part of his autobiography, but it was removed from Black Boy. His relationship with the party became difficult. Wright was threatened and attacked by former comrades.

Richard Wright's Career

In Chicago in 1932, Wright began writing with the Federal Writers' Project. He also joined the American Communist Party. In 1937, he moved to New York. He became the Bureau Chief of the communist newspaper The Daily Worker. He wrote over 200 articles for the paper from 1937 to 1938. This allowed him to write about issues that interested him. He showed what America was like during the Great Depression.

He worked on the Federal Writers' Project guide to New York City, New York Panorama (1938). He wrote the essay about Harlem for the book. He also helped edit a short-lived literary magazine called New Challenge. In 1938, Wright became good friends with writer Ralph Ellison. This friendship lasted for many years. He also won the Story magazine first prize of $500 for his short story "Fire and Cloud."

After winning the Story prize in 1938, Wright put aside his novel Lawd Today. He hired a new literary agent, Paul Reynolds. The Story Press offered Wright's prize-winning stories to the publisher Harper. Harper agreed to publish the collection.

Wright became well-known for his collection of four short stories. It was called Uncle Tom's Children (1938). Some of these stories were based on lynching in the Deep South. The success of Uncle Tom's Children improved Wright's standing with the Communist Party. It also gave him some financial stability. He joined the editorial board of New Masses. By May 1938, good sales allowed Wright to move to Harlem. There, he began writing his famous novel Native Son, which was published in 1940.

Based on his short stories, Wright received a Guggenheim Fellowship. This gave him money to finish Native Son. He rented a room with friends Herbert and Jane Newton. They were an interracial couple and prominent Communists he knew from Chicago.

After it was published, Native Son was chosen by the Book of the Month Club. It was the first book by an African-American author they selected. The main character, Bigger Thomas, is limited by society. He finds his own purpose by doing terrible things. Wright was criticized for showing so much violence in his books. People said he portrayed a Black man in a way that confirmed white people's worst fears. After Native Son was published, Wright was very busy. In July 1940, he went to Chicago. He researched a history of Black people to go with photographs by Edwin Rosskam. In Chicago, he visited the American Negro Exposition with other writers.

Wright traveled to Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He worked with playwright Paul Green to adapt Native Son for the stage. In January 1941, Wright received the important Spingarn Medal. This award was from the NAACP for his achievements. His play Native Son opened on Broadway in March 1941. Orson Welles directed it. It received good reviews. Wright also wrote text for a book of photographs by Rosskam. These photos were mostly from the Farm Security Administration. Their book, Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States, was published in October 1941. It received much praise.

Wright's memoir Black Boy (1945) tells about his early life. It covers his time from Roxie, Mississippi, until he moved to Chicago at age 19. It describes his conflicts with his Seventh-day Adventist family. It also tells about his problems with white employers and feeling alone. The book also shows his journey of learning and thinking. American Hunger, published after his death in 1977, was meant to be the second part of Black Boy. The 1991 Library of America edition finally put the two parts together.

American Hunger describes Wright's time in the John Reed Clubs and the Communist Party. He left the party in 1942, though the book suggests he left earlier. He did not announce his leaving until 1944. In the full version of the book, Wright compared communism's strictness and intolerance to strict religious groups. He disliked Joseph Stalin's Great Purge in the Soviet Union.

Life in France

After a few months in Québec, Canada, Wright moved to Paris in 1946. He became a permanent American living abroad. In Paris, Wright became friends with French writers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. He had met them in New York. He and his wife became very good friends with Simone de Beauvoir.

His interest in Existentialist ideas was shown in his second novel, The Outsider (1953). This book was about a Black American character's involvement with the Communist Party in New York. He also became friends with other American writers living in Paris, like Chester Himes and James Baldwin. His friendship with Baldwin ended badly. Baldwin wrote an essay criticizing Wright's character Bigger Thomas as being too stereotypical. In 1954, Wright published Savage Holiday.

After becoming a French citizen in 1947, Wright traveled through Europe, Asia, and Africa. He used these trips to write many non-fiction books. In 1949, Wright wrote for an anti-communist book called The God That Failed. His essay had been published earlier in the Atlantic Monthly. The FBI watched Wright starting in 1943. This was due to fears of links between Black Americans and communists. In the 1950s, with strong anti-communist feelings, Wright was blacklisted by Hollywood studios. But in 1950, he starred as the teenager Bigger Thomas in an Argentinian film version of Native Son. Wright was 42 at the time.

In 1953, Wright traveled to the Gold Coast. This country, now Ghana, was becoming independent from British rule. Before returning to Paris, he gave a secret report to the U.S. consulate in Accra. He shared what he learned about Kwame Nkrumah, the leader, and his political party. After returning to Paris, Wright met twice with an officer from the US State Department. The officer's report included what Wright learned from Nkrumah's adviser, George Padmore. Padmore believed Wright was a good friend. Wright's book about his African journey, Black Power, was published in 1954.

Historian Carol Polsgrove wondered why Wright did not write much about the growing civil rights movement in the United States during the 1950s. She found that Wright was under "extraordinary pressure" to avoid writing about the US. This was according to his friend Chester Himes. Wright believed that a white magazine would be safer for publishing his essay "I Choose Exile." He thought the Atlantic Monthly was interested, but the essay was never published.

In 1955, Wright visited Indonesia for the Bandung Conference. He wrote about his observations in The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Wright was excited about this meeting of newly independent nations. He gave lectures and interviewed artists and thinkers in Indonesia.

Other books by Wright include White Man, Listen! (1957) and the novel The Long Dream (1958). This novel was made into a play in New York in 1960. It explores the relationship between a man named Fish and his father. A collection of short stories, Eight Men, was published after Wright's death in 1961. These works mainly focused on the poverty, anger, and protests of Black Americans in northern and southern cities.

In February 1959, Wright's agent gave very negative feedback on his 400-page book, Island of Hallucinations. Despite this, Wright planned a new novel in March. By May 1959, Wright wanted to leave Paris and live in London. He felt French politics were too influenced by the United States. The peaceful atmosphere in Paris had been broken by arguments and attacks against Black expatriate writers.

On June 26, 1959, after a party, Wright became ill. He suffered from a severe case of amoebic dysentery. He likely caught it during his 1953 trip to the Gold Coast. By November 1959, his wife found an apartment in London. But Wright's illness and problems with British immigration officials ended his wish to live in England.

On February 19, 1960, Wright learned that the play The Long Dream received bad reviews in New York. The adapter decided to cancel more performances. Wright also had trouble getting The Long Dream published in France. These problems stopped him from finishing Island of Hallucinations.

In June 1960, Wright recorded discussions for French radio. He talked about his books and writing career. He also spoke about race in the United States and the world. He criticized American policy in Africa. In late September, Wright wrote descriptions for record covers. This was to help pay for his daughter Julia's move to Paris for college.

Even with money problems, Wright stuck to his beliefs. He refused to join Canadian radio programs because he suspected American control. He also turned down an invitation to speak at a conference in India. Wright helped Kyle Onstott get his novel Mandingo (1957) published in France.

Wright's last big public speech was on November 8, 1960. It was called "The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States." He argued that American society tried to control Black people who questioned racism. He used the attacks by Communists against Native Son as proof. He also mentioned arguments with James Baldwin and other authors. On November 26, 1960, Wright talked excitedly with Langston Hughes about his work Daddy Goodness. He gave Hughes the manuscript.

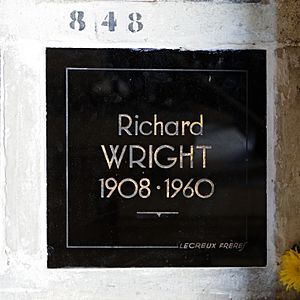

Richard Wright died in Paris on November 28, 1960, at age 52. He was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Many of Wright's works were published after his death. Some of his more powerful passages about race, sex, and politics were cut from his books when they were first published. In 1991, full versions of Native Son, Black Boy, and other works were published. In 1994, his short novel Rite of Passage was published for the first time.

In his last years, Wright loved the Japanese poetic form haiku. He wrote over 4,000 short poems. In 1998, a book called Haiku: This Other World was published. It contained 817 of his favorite haiku. Many of these poems have a hopeful feeling. They deal with feelings of loneliness, death, and nature.

A collection of Wright's travel writings was published in 2001. When he died, Wright left an unfinished book, A Father's Law. His daughter Julia Wright published it in January 2008. A collection of Wright's political works was published. It was titled Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain; and White Man, Listen!.

Richard Wright's Family Life

In August 1939, Richard Wright married Dhimah Rose Meidman. She was a modern-dance teacher. Ralph Ellison was his best man. This marriage lasted only one year.

On March 12, 1941, he married Ellen Poplar. She was a Communist organizer from Brooklyn. They had two daughters: Julia, born in 1942, and Rachel, born in 1949.

Ellen Wright died on April 6, 2004, at age 92. She managed Wright's literary works. She was also a literary agent. Her clients included Simone de Beauvoir and Eldridge Cleaver.

Awards and Honors for Richard Wright

- The Spingarn Medal in 1941 from the NAACP.

- Guggenheim Fellowship in 1939.

- Story Magazine Award in 1938.

- In April 2009, Wright was featured on a U.S. postage stamp. This stamp was part of the literary arts series. It showed a picture of Wright in front of snowy buildings in Chicago. This scene reminded people of Native Son.

- In 2010, Wright was added to the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

- In 2012, a cultural medallion was placed at 175 Carlton Avenue, Brooklyn. This was where Wright lived in 1938. He finished Native Son there.

Richard Wright's Legacy

Black Boy became a best-seller right after it was published in 1945. Some critics were disappointed by Wright's stories in the 1950s. They said his move to Europe made him lose touch with Black Americans.

During the 1950s, Wright became more focused on global issues. He achieved a lot as a public writer and political figure worldwide. However, his creative writing became less strong.

While interest in Black Boy slowed in the 1950s, it remains one of his best-selling books. Since the late 1900s, there has been new interest in it. Black Boy is still an important book. It shows a Black man's search for himself in a racist society. It greatly influenced later Black American writers. These include James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison.

Most people agree that Native Son influenced ideas and attitudes. It was important in the social and intellectual history of the United States in the last half of the 20th century. Writer Amiri Baraka said, "Wright was one of the people who made me conscious of the need to struggle."

In the 1970s and 1980s, scholars wrote critical essays about Wright. Richard Wright conferences were held at universities. A new film version of Native Son was released in December 1986. Some of Wright's novels became required reading in high schools and colleges.

Recent critics have asked for a new look at Wright's later work. They want to consider his philosophical ideas. Paul Gilroy argued that his deep philosophical interests have often been missed.

Wright was featured in a 90-minute film called Soul of a People: Writing America's Story (2009). This film was about the WPA Writers' Project. His life and work in the 1930s are highlighted in the book that goes with the film.

See also

In Spanish: Richard Wright (escritor) para niños

In Spanish: Richard Wright (escritor) para niños

- Richard Thomas Gibson

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |