Rudd Concession facts for kids

|

|

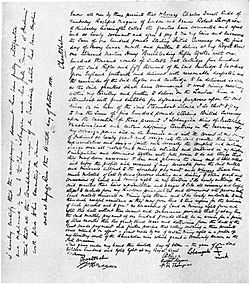

| Signed | 30 October 1888 |

|---|---|

| Location | Bulawayo, Matabeleland |

| Depositary | British South Africa Company (from 1890) |

The Rudd Concession was a written agreement. It gave special rights to mine for minerals in a large area of southern Africa. This area is now part of Zimbabwe.

King Lobengula of Matabeleland signed this agreement. He gave the rights to Charles Rudd, James Rochfort Maguire, and Francis Thompson. These men worked for Cecil Rhodes, a powerful businessman and politician. The agreement was signed on 30 October 1888.

Even though King Lobengula later tried to cancel it, the Rudd Concession was very important. It helped Cecil Rhodes get a special permission, called a royal charter, from the United Kingdom in 1889. This charter allowed Rhodes's British South Africa Company to take control of the land.

In 1890, a group called the Pioneer Column moved into Mashonaland. This started white settlement and rule in the area. The country eventually became known as Rhodesia, named after Cecil Rhodes.

Rhodes wanted to add these lands to the British Empire. He dreamed of building a Cape to Cairo Railway across Africa. Getting the mining rights was a key step. It would help him get the royal charter from the British government. This charter would let his company govern the land between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers.

Rhodes prepared for the agreement in early 1888. He helped arrange a friendship treaty between the British and the Matabele. Then, he sent Rudd's team from South Africa to get the mining rights. Rudd's team raced against another rival, Edward Arthur Maund. After long talks with King Lobengula and his tribal leaders (called izinDuna), Rudd succeeded.

The concession gave Rudd's team the only rights to mine throughout Lobengula's country. It also allowed them to use force to protect these rights. In return, Lobengula would receive weapons and regular payments. In early 1889, the king tried to cancel the document. He said that Rudd's team had tricked him about the terms. The king believed that some rules about the mining activities had been agreed verbally. He tried to convince the British government to say the concession was not valid. He even sent people to meet Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. But his efforts did not work.

After Rhodes and a London group agreed to work together, Rhodes went to London. He arrived in March 1889. His request for a charter gained a lot of support. This led the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, to approve the royal charter. It was officially given in October 1889. Rhodes's Company took over Mashonaland about a year later. Lobengula tried to create a rival agreement in 1891. He gave similar rights to a German businessman named Eduard Lippert. But Rhodes quickly bought this agreement too. Company soldiers took over Matabeleland during the First Matabele War of 1893–1894. King Lobengula died from smallpox soon after, while in exile.

Contents

History of the Agreement

The Matabele People

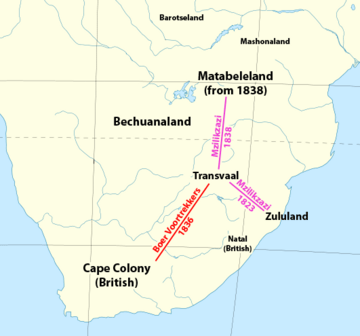

In the 1810s, the Zulu Kingdom was formed in southern Africa. A warrior king named Shaka united many groups. One of Shaka's main leaders was Mzilikazi. But Mzilikazi angered the king and had to leave in 1823. He and his followers moved north-west to the Transvaal. There, they became known as the Ndebele or "Matabele." Both names mean "men of the long shields."

This was a time of war and chaos, called mfecane ("the crushing"). The Matabele quickly became the strongest group in the area. In 1836, they made a peace treaty with the British. But the same year, Boer settlers called Voortrekkers moved into the area. They were moving away from British rule. These new settlers soon defeated Mzilikazi. He had to lead another move north in 1838. The Matabele crossed the Limpopo River and settled in the south-west. This area has been called Matabeleland ever since.

Matabele culture was much like the Zulus'. Their language, Sindebele, was based on Zulu. Matabeleland had a strong military tradition. Men were trained to be disciplined warriors. Tribal leaders, called izinDuna, helped the king (inkosi) with military and civilian matters. A group of warriors was called an impi. The Mashona people lived in the north-east. They were more numerous but militarily weaker. They largely paid tribute to the Matabele.

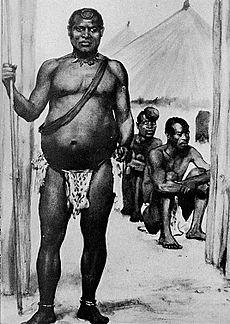

After Mzilikazi died in 1868, his son Lobengula became king in 1870. Lobengula was tall and wise. At first, he welcomed Western businesses. He wore Western clothes and gave mining and hunting permits to white visitors. In return, he received money, weapons, and ammunition.

Because the king could not read or write, white people at his royal village (kraal) in Bulawayo prepared the documents. To make sure the writing was correct, Lobengula had his words translated. Then, another person translated them back to him. Once he was happy, he would sign with his mark. He would also use his royal seal, which showed an elephant. Other white men would then sign as witnesses.

For unknown reasons, Lobengula's attitude changed in the late 1870s. He stopped wearing Western clothes and limited white people's movement. But white people kept coming, especially after gold was found in the South African Republic (Transvaal) in 1886. This started the Witwatersrand Gold Rush. Rumours of even richer gold north of the Limpopo River spread. Miners began to seek agreements from Lobengula to search for gold. Most of these efforts failed. Only the Tati Concession, a small area on the border, had mining operations since 1868.

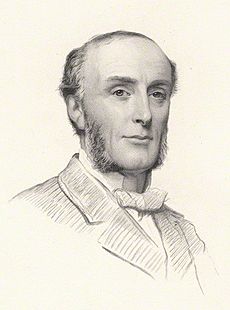

At this time, Cecil Rhodes was the most important businessman and politician in southern Africa. He had arrived from England in 1870, at age 17. Rhodes had become very powerful in the diamond trade. He controlled most of the world's diamond production with help from Charles Rudd and Alfred Beit. Rhodes was also a member of the Cape Parliament.

During the European "Scramble for Africa", Rhodes dreamed of adding lands to the British Empire. He wanted to connect the Cape (southern Africa) to Cairo (Egypt) with a railway. The Boer republics and Lobengula's lands stood in his way. Also, the Zambezi–Limpopo region was not claimed by any European power at the Berlin Conference (1884–85). The Transvaalers, Germans, and Portuguese were all interested in the area. This worried both Lobengula and Rhodes.

The Moffat Treaty

Rhodes started pushing for Britain to take Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1887. He put pressure on important British officials. One was Sir Hercules Robinson, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa. Another was Sidney Godolphin Alexander Shippard, Britain's administrator in Bechuanaland. Shippard, an old friend of Rhodes, soon agreed. In May 1887, he wrote to Robinson, strongly supporting the idea. He called Mashonaland "the most valuable country south of the Zambezi."

However, the Boers were the first to make a deal with Lobengula. Pieter Grobler secured a "renewal of friendship" treaty in July 1887. In the same month, Robinson appointed John Smith Moffat, a missionary, as assistant commissioner in Bechuanaland. Moffat knew Lobengula well. The British hoped he could make the king less friendly with the Boers and more pro-British.

In September 1887, Robinson wrote to Lobengula through Moffat. He urged the king not to grant any agreements to Transvaal, German, or Portuguese agents without asking Moffat first. Moffat reached Bulawayo on 29 November. Grobler was still there. The exact details of the Grobler treaty were not public. Newspapers in South Africa reported that Matabeleland had become a protectorate of the South African Republic. Moffat asked questions in Bulawayo. Grobler denied the reports. The king said it was just a renewal of an old peace treaty.

In Pretoria, another British agent met Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic. Kruger reportedly said his government now saw Matabeleland as under Transvaal "protection and sovereignty." He claimed one part of the Grobler treaty said Lobengula could not make any agreements without Pretoria's approval. Rhodes, Shippard, and Robinson met on Christmas Day. They decided to tell Moffat to investigate. They also wanted him to get a copy of the Grobler treaty. They planned for a formal British-Matabele treaty. This new treaty would stop Lobengula from making more agreements with foreign powers other than Britain.

Lobengula was worried about how people saw his dealings with Grobler. So, he did not want to sign more agreements. Even though he knew Moffat, the king was careful. He was not sure about fully siding with the British. Moffat said the Matabele leaders "may like us better, but they fear the Boers more." Moffat's talks with the king and izinDuna were long and difficult. The missionary presented the British treaty as a renewal of an old agreement from 1836. He told the Matabele that the Boers were misleading them. He said the British proposal was better for the Matabele.

On 11 February 1888, Lobengula agreed. He signed the document. The agreement said the Matabele and British were now at peace. Lobengula would not talk to any country except Britain about diplomatic matters. He also would not "sell, alienate or cede" any part of Matabeleland or Mashonaland to anyone.

The document only described what Lobengula would do. Shippard was unsure about this. He also noted that none of the izinDuna had signed. He asked Robinson if they should negotiate another treaty. Robinson said no. He thought reopening talks so soon would make Lobengula suspicious. Britain's ministers in London saw the treaty's one-sided nature as good for Britain. It did not commit the British government to any specific actions.

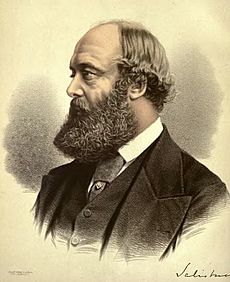

Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister, decided that Moffat's treaty was stronger than Grobler's. Even though it was signed later, the London Convention of 1884 stopped the South African Republic from making treaties with any state except the Orange Free State. Treaties with "native tribes" north of the Limpopo were allowed. But the Prime Minister claimed Matabeleland was too organized to be just a tribe. He said it should be seen as a nation. Because of this, he said the Grobler treaty was not legally valid. London soon allowed Robinson to approve the Moffat agreement. It was announced in Cape Town on 25 April 1888.

For Rhodes, Moffat's agreement was very important. It gave him time to combine his diamond businesses. Lobengula could have moved his people across the Zambezi. But Rhodes wanted to keep the king where he was. This would act as a barrier against Boer expansion. In March 1888, Rhodes bought out his last competitor. He formed De Beers Consolidated Mines. This huge company controlled 90% of the world's diamond production.

Rhodes wanted De Beers to do more than just mine diamonds. He wanted to use the company to "win the north." The company's rules allowed it to do many things. These included banking, building railways, taking over and governing land, and even raising armies. This gave the rich company powers similar to the East India Company. That company had governed India for Britain. Through De Beers and Gold Fields of South Africa, Rhodes had the money and power to build his African empire. But to do this, he needed a royal charter. This charter would allow him to take control of the lands for Britain. To get the charter, he needed a signed agreement from a local ruler. This agreement would give him exclusive mining rights in the lands he wanted.

The Concession Agreement

The Race to Bulawayo

Rhodes faced competition for the Matabeleland mining agreement. George Cawston and Lord Gifford, two London financiers, were also interested. They sent Edward Arthur Maund as their agent. Maund had visited Lobengula before as a British envoy. Cawston and Gifford were based in England. This gave them better connections with the British government. Rhodes was in the Cape. This allowed him to see the situation directly. He also had a lot of money and close ties with colonial officials. In May 1888, Cawston and Gifford wrote to Lord Knutsford, the British Colonial Secretary. They asked for his approval.

Rhodes realized the urgency of getting the agreement during a visit to London in June 1888. He learned about the London group's letter to Knutsford and Maund's appointment. Rhodes understood that the Matabeleland agreement could still go to someone else if he did not act fast. "Someone has to get the country," Rhodes told Rothschild. "I think we should have the best chance." He added, "I have always been afraid of the difficulty of dealing with the Matabele king. He is the only block to central Africa... I have faith in the country, and Africa is on the move."

Rhodes and Beit chose Rudd to lead their new team. Rudd had a lot of experience buying farms from Boers for gold prospecting. Rudd knew little about African customs and languages. So, Rhodes added Francis "Matabele" Thompson. Thompson had worked for Rhodes for years. He managed the living areas for black workers at the diamond fields. Thompson spoke Setswana fluently, a language Lobengula also knew. This meant he could talk directly with the king. James Rochfort Maguire, an Irish lawyer, was the third member. Rhodes had known him at Oxford.

Many people wonder why Maguire was included. Some think he was there to write the document in complex legal language. This would make it hard to challenge. But the agreement was not that complicated. Historian Robert I. Rotberg suggests Rhodes wanted Maguire to add "culture and class" to the trip. This might impress Lobengula and rival groups. The London group had the social standing of Lord Gifford. Rhodes hoped Maguire would balance this. Rudd's team included Rudd, Thompson, Maguire, their Dutch wagon driver J. G. Dreyer, another white man, a mixed-race person from the Cape, an African American, and two black servants.

Maund arrived in Cape Town in late June 1888. He tried to get Robinson's approval for the Cawston–Gifford offer. Robinson was careful in his answers. He supported developing Matabeleland. But he said he could not support Cawston and Gifford exclusively. Not without clear instructions from London. Rudd's team was still getting ready in Kimberley. Maund traveled north and reached the diamond mines in early July. On 14 July, in Bulawayo, agents for Thomas Leask received a mining agreement from Lobengula. It covered all his country and promised half the profits to the king. Leask was upset by this condition. He said the agreement was "commercially valueless." Moffat told Leask that his group did not have the resources to use the agreement. He suggested Leask wait and sell his agreement to whichever big group got a new deal from Lobengula. Rhodes's group, the Cawston–Gifford group, and the British officials did not immediately know about the Leask agreement.

In early July 1888, Rhodes returned from London. He met with Robinson. Rhodes proposed creating a chartered company to govern and develop south-central Africa. He would lead it. It would have powers similar to other British chartered companies. Rhodes said this company would take control of parts of Matabeleland and Mashonaland not used by local people. It would set aside areas for the local population. Then, it would protect and develop these lands. Rhodes said this would protect Matabele and Mashona interests. It would also develop south-central Africa without costing the British government any money.

Robinson wrote to Knutsford on 21 July. He thought London should support this idea. He believed the Boers would accept British expansion better if it came from a chartered company. This would be better than creating a new Crown colony. He also wrote a letter for Rudd's team to carry to Bulawayo. It recommended Rudd and his companions to Lobengula.

Maund left Kimberley in July, well before Rudd's team. Rudd's team, with Robinson's support, was still not ready. They left Kimberley on 15 August. But Moffat, traveling from Shoshong in Bechuanaland, was ahead of both. He reached Bulawayo in late August. The village was full of white people seeking agreements. They tried to impress the king with gifts, but had little success.

Between Kimberley and Mafeking, Maund learned that Grobler had been killed by Ngwato warriors. The Boers were threatening to attack the British-protected Ngwato chief, Khama III. Maund offered to help Khama. He wrote to his employers, saying this might help get an agreement from Khama. Cawston quickly wrote back, ordering Maund to go to Bulawayo at once. But over a month had passed, and Maund had lost his lead over Rudd. The Rudd party ignored a notice from Lobengula. It banned white hunters and concession-seekers. They arrived at the king's village on 21 September 1888, three weeks before Maund.

Negotiations for the Concession

Rudd, Thompson, and Maguire immediately met Lobengula. The king came out and greeted them politely. Through a Sindebele interpreter, Rudd introduced himself and his team. He explained who they worked for and said they came for a friendly visit. He gave the king a gift of £100.

After a few days, Thompson explained their business to the king in Setswana. He said his backers did not want land, unlike the Transvaalers. They only wanted to mine gold in the Zambezi–Limpopo area. Talks happened off and on for weeks. Moffat, who stayed in Bulawayo, sometimes advised the king. He subtly helped Rudd's team. He told Lobengula to work with one large company instead of many small ones. This would be easier to manage. He also told the king that Shippard would visit in October. He advised Lobengula to wait until after that visit to decide.

Shippard arrived in mid-October 1888 with Sir Hamilton Goold-Adams and 16 policemen. The king stopped talks about the agreement to meet with Shippard. The British official told the king that the Boers wanted more land and planned to take over his country. He also supported Rudd's cause. He told Lobengula that Rudd's team worked for a powerful, rich organization supported by Queen Victoria. Meanwhile, Rhodes sent letters to Rudd. He warned that Maund was his main rival. He said it was important to defeat Cawston and Gifford or bring them into Rhodes's group. Regarding Lobengula, Rhodes told Rudd to make the king think the agreement would benefit him. "Offer a steamboat on the Zambezi... Stick to Matabeleland for the Matabele. I am sure it is the ticket."

As October ended, Rudd wanted to return to the Witswatersrand gold mines. But Rhodes insisted he could not leave Bulawayo without the agreement. "You must not leave a vacuum," Rhodes ordered. "Leave Thompson and Maguire if necessary or wait until I can join... if we get anything we must always have someone resident." So, Rudd stayed. He tried hard to convince Lobengula to negotiate directly. But the king kept refusing. Lobengula only agreed to look at the draft document, mostly written by Rudd, just before Shippard was to leave. At this meeting, Lobengula discussed the terms with Rudd for over an hour. Charles Helm, a local missionary, was called to interpret. According to Helm, Rudd made several promises to Lobengula that were not in the written document. These included bringing no more than 10 white men to work, not digging near towns, and that they would follow the king's laws.

After these talks, Lobengula called a big meeting (indaba) of over 100 izinDuna. He presented the proposed terms to them to see what they thought. Opinions were divided. Most younger izinDuna were against any agreement. The king and many older izinDuna were open to Rudd's offer. A mining monopoly by Rudd's powerful backers was appealing. It would stop many small prospectors from bothering them. But some argued for allowing competition to continue. This would make rival miners compete for Lobengula's favor.

For many at the indaba, the most important thing was Matabeleland's safety. Lobengula thought the Transvaalers were stronger fighters than the British. But he knew Britain was more powerful globally. The Boers wanted land. Rudd's group claimed to only want mining and trading rights. Lobengula thought that if he accepted Rudd's offer, he would keep his land. And the British would have to protect him from the Boers.

Rudd offered very generous terms. Few competitors could match them. If Lobengula agreed, Rudd's backers would give the king 1,000 Martini–Henry rifles. They would also give 100,000 rounds of ammunition. Plus, a steamboat on the Zambezi (or £500 cash if the king preferred). And £100 every month forever. The weapons impressed the king more than the money. He had 600 to 800 rifles, but almost no ammunition. This deal would give him many firearms and bullets. This could be very important if there was a conflict with the South African Republic. The weapons might also help him control his own more unruly impis. Lobengula had Helm read the document to him many times. He wanted to make sure he understood it well. None of Rudd's spoken promises were in the written document. This meant they were not legally binding. But the king seemed to think they were part of the deal.

The final talks began at the royal village on the morning of 30 October. The izinDuna and Rudd's team met. The king was nearby but did not attend. The izinDuna asked Rudd and his companions where exactly they planned to mine. They replied they wanted rights covering "the whole country." When the izinDuna hesitated, Thompson insisted, "No, we must have Mashonaland, and right up to the Zambezi as well—in fact, the whole country." According to Thompson, this confused the izinDuna. They did not seem to know where these places were. "The Zambezi must be there," one said, pointing south instead of north. The Matabele representatives then dragged out the talks. Rudd and Thompson announced they were done and stood to leave. The izinDuna were worried and asked them to stay. They did. Then, it was agreed that inDuna Lotshe and Thompson would tell the king about the day's progress.

The Agreement is Signed

After talking with Lotshe and Thompson, the king was still unsure. Thompson asked Lobengula a question: "Who gives a man a spear if he expects to be attacked by him afterwards?" This referred to the Martini–Henry rifles offered. Lobengula was convinced by this idea. He decided to grant the agreement. "Bring me the fly-blown paper and I will sign it," he said. Thompson quickly left to call Rudd, Maguire, Helm, and Dreyer. They sat in a half-circle around the king.

As Lobengula signed his mark on the paper, Maguire said to Thompson, "Thompson, this is the most important moment of our lives." After Rudd, Maguire, and Thompson signed, Helm and Dreyer added their signatures as witnesses. Helm also wrote an endorsement next to the terms.

Lobengula did not allow any of the izinDuna to sign the document. The reason for this is not clear. Rudd thought the king felt they had already been consulted at the day's meeting. So, he did not think they needed to sign. Some historians suggest Lobengula might have thought it would be harder to cancel the document later if his izinDuna had also signed it.

Dispute Over the Agreement

Lobengula's Trip to England

Lobengula told Thompson and Maguire that he was only denying that he had given his country away. He said he would still respect the agreement itself. He asked Maund to go with two of his izinDuna, Babayane and Mshete, to England. They would meet Queen Victoria. Officially, they would give her a letter complaining about Portuguese actions in Mashonaland. Unofficially, they would ask for advice about the situation in Bulawayo. The mission also aimed to see if this white queen, whom the British spoke of, really existed. The king's letter also asked the Queen to send her own representative to Bulawayo. Maund saw a chance to get his own agreement. He was happy to help. But Lobengula remained careful with him. When Maund asked about a new agreement for the Mazoe valley, the king replied, "Take my men to England for me; and when you return, then I will talk about that." Johannes Colenbrander, a frontiersman from Natal, was hired to interpret for the Matabele visitors. They left in mid-December 1888.

Around this time, a group of prospectors tried to get their own mining agreement from Lobengula. The king honored the Rudd Concession. He allowed Maguire to lead a Matabele impi to turn the prospectors away. While Robinson's letter to Knutsford traveled to England, the Colonial Secretary learned about the Rudd Concession from Cawston and Gifford. Knutsford asked Robinson on 17 December if it was true that 1,000 Martini–Henrys were part of the deal. He asked, "If rifles part of consideration, as reported, do you think there will be danger of complications arising from this?" Robinson replied in writing. He included a note from Shippard. Shippard explained how the agreement happened. He said the Matabele were less experienced with rifles than with spears. So, getting rifles would not make them deadly. He also argued it would not be fair to give other chiefs firearms but not Lobengula. He thought a well-armed Matabeleland might stop Boer interference.

Rhodes was surprised by the news of a Matabele mission to London. He tried to downplay the importance of the izinDuna and stop them from leaving Africa. When the envoys reached Kimberley, Rhodes told his friend, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, to invite Maund to their house. Maund was suspicious but came. Rhodes offered Maund money and job benefits to leave the London group. Maund refused. Rhodes angrily said he would have Robinson stop their trip at Cape Town. The izinDuna reached Cape Town in mid-January 1889. They found that Rhodes was right. To delay their departure, Robinson sent messages to London. He said Maund was "mendacious" (lying) and "dangerous." He called Colenbrander "hopelessly unreliable." He also said Babayane and Mshete were not really izinDuna or even headmen. Cawston sadly told Maund by telegram that it was useless to continue while Robinson acted this way.

Rhodes and the London Group Join Forces

Rhodes then arrived in Cape Town to talk with Maund again. His mood was very different. After reading Lobengula's message to Queen Victoria, he said he believed the Matabele trip to England could actually help his plans. This would happen if the London group agreed to combine their interests with his. They would form one big company. He told Maund to send this idea to his employers. Maund thought Rhodes's change of mind was because of his own influence and the threat from the Matabele mission. But actually, the idea to unite came from Knutsford. The month before, Knutsford had suggested to Cawston and Gifford that they would more likely get a royal charter if they joined forces with Rhodes. They had sent a message to Rhodes, who then came back to Maund. The joining of forces ended the long fight between Rhodes and his London rivals. Both sides were happy. Cawston and Gifford could now use Rhodes's money and political power. And Rhodes's Rudd Concession was more valuable now that the London group no longer challenged it.

There was still the issue of Leask's agreement. Rudd's team had learned about it in Bulawayo in late October. Rhodes decided it must be bought. "I quite see that worthless as [Leask's] concession is, it logically destroys yours," he told Rudd. This problem was solved in late January 1889. Rhodes met and settled with Leask and his partners in Johannesburg. Leask received £2,000 cash and a 10% share in the Rudd Concession. He also kept a 10% share in his own agreement with Lobengula. His partners received £300 each per year. In Cape Town, with Rhodes's opposition gone, Robinson changed his mind about the Matabele mission. He sent a message to London. He said further checks showed Babayane and Mshete were headmen after all. So, they should be allowed to sail for England.

Lobengula's Questions

Meanwhile, in Bulawayo, South African newspaper reports about the agreement started arriving in mid-January 1889. William Tainton, a white resident, translated a newspaper clipping for Lobengula. He added his own details. He told the king that he had sold his country. He said the miners could dig anywhere, even in villages. And they could bring an army to remove Lobengula and put a new chief in charge. The king told Helm to read and translate the copy of the agreement that stayed in Bulawayo. Helm did so. He pointed out that none of Tainton's claims were in the text. Lobengula then said he wanted to make an announcement. Helm refused to write it. So, Tainton translated and wrote down the king's words:

This notice was printed in the Bechuanaland News and Malmani Chronicle on 2 February 1889. A large meeting (indaba) of the izinDuna and the white people of Bulawayo was soon called. But Helm and Thompson were not there. So, the investigation was delayed until 11 March. As in the earlier talks, Lobengula did not attend himself. He stayed nearby but did not interfere. The izinDuna questioned Helm and Thompson for a long time. Various white men gave their opinions on the agreement. A group of missionaries helped as mediators. The agreement was criticized not by the izinDuna, but by other white people, especially Tainton.

Tainton and other white opponents argued that the document gave the miners all the minerals, lands, wood, and water. They said it was like buying the whole country. Thompson, supported by the missionaries, insisted the agreement only covered taking out metals and minerals. He said anything else the miners did was covered by the agreement's right "to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure" the mining yield. William Mzisi, a man from the Cape, had been to the diamond fields. He pointed out that mining would need thousands of men, not just a few, as Lobengula thought. He argued that digging into the land meant taking possession of it: "You say you do not want any land, how can you dig for gold without it, is it not in the land?" Thompson was then asked where exactly it had been agreed that the miners could dig. He confirmed that the document allowed them to search and dig anywhere in the country.

Some of the izinDuna saw Helm as suspicious. This was because all white visitors to Bulawayo met with him before seeing the king. This feeling grew because Helm had been Lobengula's postmaster. He handled all mail coming into Bulawayo. He was accused of hiding the agreement's true meaning from the king. He was also accused of purposely lowering the prices traders paid for cattle. But neither of these charges could be proven. On the fourth day of the investigation, two missionaries were asked if exclusive mining rights in other countries could be bought for similar amounts, as Helm claimed. They said no. The izinDuna concluded that either Helm or the missionaries were lying. The missionaries tried to convince Lobengula that honest men do not always agree. But they had little success.

During the investigation, Thompson and Maguire received threats. Maguire, not used to the African bush, caused problems with his habits. One day, he cleaned his false teeth in what the Matabele considered a sacred spring. He accidentally dropped some perfume into it. The angry locals thought he was poisoning the spring. They also claimed Maguire practiced witchcraft and rode hyenas at night.

Rhodes sent the first shipments of rifles to Bechuanaland in January and February 1889. He sent 250 each month. He told Jameson and others to take them to Bulawayo. Lobengula had accepted the money payments from the Rudd Concession. He continued to do so for years. But when the guns arrived in early April, he refused them. Jameson put the weapons under a canvas cover in Maguire's camp. He stayed for ten days, then went south with Maguire, leaving the rifles. A few weeks later, Lobengula dictated a letter to the Queen. He said he had never meant to sign away mineral rights. He and his izinDuna canceled their recognition of the document.

Babayane and Mshete in England

After a long delay, Babayane, Mshete, Maund, and Colenbrander traveled to England. They arrived in Southampton in early March 1889. They went by train to London and stayed at the Berners Hotel. After two days, they were invited to Windsor Castle. The meeting was supposed to be only for the two izinDuna and their interpreter. Maund could not attend because he was a British subject. But Knutsford made an exception for Maund. This was because Babayane and Mshete refused to go without him. The Colonial Secretary said it would be a shame if the visit failed over a small rule. The visitors met the Queen. They gave her the letter from Lobengula and a spoken message.

The izinDuna stayed in London throughout March. They attended many dinners in their honor. One was hosted by the Aborigines' Protection Society. The Society sent a letter to Lobengula. It advised him to be "wary and firm in resisting proposals that will not bring good to you and your people." The diplomats saw many sights in London. These included London Zoo, the Alhambra Theatre, and the Bank of England. Their hosts showed them the spear of the Zulu king Cetshwayo. It hung on a wall at Windsor Castle. They also went to Aldershot to watch military exercises.

Knutsford held two more meetings with the izinDuna. In the second meeting, he gave them the Queen's reply to Lobengula's letter. It mostly contained general promises of goodwill. Satisfied, the visitors sailed home.

Rhodes Wins the Royal Charter

In late March 1889, as the izinDuna were leaving London, Rhodes arrived. He made the joining of his company with Cawston and Gifford's official. To their dismay, the Colonial Office had received protests against the Rudd Concession. These came from London businessmen and humanitarian groups. The Colonial Office decided it could not approve the agreement. This was because it was unclear and Lobengula had announced its cancellation. Rhodes was angry with Maund at first. He blamed him for this. But he later accepted it was not Maund's fault. Rhodes told Maund to go back to Bulawayo. He should pretend to be a neutral adviser. He should try to convince the king to support the agreement again. As a backup plan, he told Maund to get as many new smaller agreements as he could.

In London, as the companies formally joined, Rhodes and Cawston looked for public members for their new company's board. They chose the Duke of Abercorn, a rich Irish nobleman, to lead the company. The Earl of Fife was chosen as his deputy. He was soon to become the Duke of Fife after marrying the Prince of Wales's daughter. The third public member was Albert Grey, a strong supporter of the British Empire. He was already connected to southern Africa. To gain favor with Lord Salisbury, Rhodes gave the Prime Minister's son, Lord Robert Cecil, a position in the proposed company. Horace Farquhar, a well-known London financier, joined the board later.

Rhodes spent the next few months in London. He sought supporters for his cause. These efforts gained public backing from important people. These included Harry Johnston and Lord Balfour of Burleigh. With Grey's help and Lord Salisbury's continued support, Rhodes seemed to be succeeding by June 1889. The merger with the London group was complete. The British government seemed to have dropped its doubts about the Rudd Concession's validity. Opposition to the charter in parliament had mostly stopped. With help from Rhodes's press contacts, like William Thomas Stead, the media began to support the idea of a chartered company for south-central Africa. But in June 1889, just as the Colonial Office was about to grant the royal charter, Lobengula's letter canceling the Rudd Concession arrived in London. He had written it two months earlier.

Maguire, in London, quickly wrote to the Colonial Office. He questioned the letter's truthfulness. He said it lacked the signature of an unbiased missionary. He also wrote to Thompson, who was still in Bulawayo. He asked if there was any sign that the king had been misled when writing the cancellation letter. Around the same time, Robinson's strong attacks on those who opposed the Rudd Concession in parliament led to Lord Salisbury replacing him with Sir Henry Brougham Loch. Rhodes claimed not to be worried. He told Shippard in a letter that "the policy will not be altered." Indeed, by the end of June 1889, Rhodes had gotten his way. Despite Robinson's removal and the stir caused by Lobengula's letter, Lord Salisbury approved the royal charter. This was due to his worries about Portuguese and German expansion in Africa, and Rhodes's efforts in London. Rhodes returned to the Cape victorious in August 1889. In London, Cawston oversaw the final steps for the chartered company's creation.

"My part is done," Rhodes wrote to Maund. "The charter is granted supporting Rudd Concession and granting us the interior... We have the whole thing recognized by the Queen." He added that even if there were problems with King Lobengula, the British would now always recognize them as owning the minerals. They understood that "savage potentates frequently repudiate" (often cancel agreements). A few weeks later, he wrote to Maund again. With the royal charter, "whatever [Lobengula] does now will not affect the fact that when there is a white occupation of the country our concession will come into force provided the English and not Boers get the country." On 29 October 1889, almost exactly a year after the Rudd Concession was signed, Rhodes's company, the British South Africa Company, officially received its royal charter from Queen Victoria. The agreement's legality was now protected by the charter and the British Crown. This made it almost impossible to challenge.

What Happened Next

Taking Over Mashonaland

Hover your mouse over each man for his name; click for more details.

Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in July 1890. He had wide support. He announced that his first goal was to take over the Zambezi–Limpopo area. His Chartered Company had by then formed the Pioneer Column. This was a group of a few hundred volunteers. Their job was to occupy Mashonaland and start developing it. The group included men from all parts of southern African society. Rhodes insisted that several sons of leading Cape families join. Each pioneer was promised 3,000 acres (12 km²) of land and 15 mining claims for their service.

Lobengula quietly agreed to the expedition. His friend Jameson had asked him to. But many of the izinDuna were angry. They saw the column's march as taking Matabele land. The pioneers were led by Major Frank Johnson and the famous hunter Frederick Courteney Selous. They were guarded by 500 British South Africa Company's Police. The pioneers avoided Lobengula's main lands. They went north-east from Bechuanaland, then north. They founded Fort Tuli, Fort Victoria, and Fort Charter along the way. They stopped at the future capital, Fort Salisbury (named after the Prime Minister), on 12 September 1890. They raised the Union Jack flag the next morning.

Running Mashonaland did not immediately make money for the Company. This was partly because of the expensive police force. Rhodes greatly reduced its size in 1891 to save money. There was also a problem with land ownership. Britain recognized the Company's right to minerals in Mashonaland. But it did not recognize its ownership of the land itself. So, the Company could not give land titles or collect rent from farmers.

The Lippert Concession

Edward Renny-Tailyour worked for Eduard Lippert, a businessman from Hamburg. He had been trying to get an agreement from Lobengula since early 1888. Rhodes saw Lippert's actions as unwanted interference. He tried many times to settle with him, but failed. In April 1891, Renny-Tailyour announced a deal with Lobengula. For £1,000 upfront and £500 yearly, the king would give Lippert the only rights to manage lands, set up banks, make money, and trade in the Company's territory.

The truthfulness of this document was questioned. The only witnesses who signed it, besides inDuna Mshete, were Renny-Tailyour's partners. One of them soon said that Lobengula believed he was giving the agreement to "Offy" Shepstone, with Lippert just acting as an agent. So, the Lippert agreement had several possible flaws. But Lippert was still sure he could get a high price for it from the Chartered Company. He asked for £250,000 in cash or shares.

Rhodes, supported by Loch, first called the Lippert agreement a fraud. He called Lippert's local agents enemies of peace. Loch assured Rhodes that if Lippert tried to make his agreement public, he would issue a warning. He would say it violated the Rudd Concession and the Company's charter. He would threaten Lippert's partners with legal action. The Colonial Office agreed with Loch. Rhodes first said he would not pay Lippert's price, calling it blackmail. But after talking with Beit, he decided that refusing to buy out Lippert might lead to long and expensive court cases. They were not sure they would win. Rhodes told Beit to start negotiating.

Lippert's agreement turned out to be a good thing for Rhodes. It included land rights from Lobengula. The Chartered Company did not have these rights. It needed them to be recognized by the British government as legally owning the occupied land in Mashonaland. After two months and several failed talks, Rudd took over the negotiations. He and Lippert agreed on 12 September 1891. The Company would take over the agreement from Lippert. But Lippert had to return to Bulawayo and have Lobengula formally approve it. In return, the Company would give Lippert 75 square miles (194 km²) of land in Matabeleland (with full land and mineral rights). He would also get 30,000 shares in the Chartered Company and other money benefits.

This plan depended on Lobengula still believing that Lippert was working against Rhodes, not for him. Moffat, the missionary, was very troubled by this "palpable immorality" (obvious dishonesty). But he agreed not to interfere. He decided Lobengula was as untrustworthy as Lippert. With Moffat as a witness, Lippert did his part of the deal in November 1891. He got exclusive land rights for a century from the Matabele king. This included permission to set up farms and towns and collect rent. This replaced what had been agreed in April. As planned, Lippert sold these rights to the Company. Then Loch approved the agreement. He was happy that the Company's land rights problem was solved. The Matabele did not know about this trick until May 1892.

Conquest of Matabeleland: The End of Lobengula

Lobengula's weakened Matabele kingdom lived uneasily with Rhodes's Company settlements for about another year. The king was angry that Company officials did not respect his authority. They insisted his kingdom was separated from Company land by a line. They also demanded he stop the traditional raids on Mashona villages by Matabele impis. In July 1893, Matabele warriors began killing Mashonas near Fort Victoria. Jameson, who Rhodes had made Company administrator in Mashonaland, tried to stop the violence. He held a meeting (indaba), but it failed. Lobengula complained that the Chartered Company had "come not only to dig the gold but to rob me of my people and country as well." Rhodes, watching from Cape Town, asked Jameson by telegram if he was ready for war: "Read Luke 14:31".![]() Jameson replied: "All right. Have read Luke 14:31".

Jameson replied: "All right. Have read Luke 14:31".

On 13 August 1893, Lobengula refused to accept the monthly payment from the Rudd Concession. He called it "the price of my blood." The next day, Jameson signed a secret agreement with settlers at Fort Victoria. He promised each man 6,000 acres (24 km²) of farmland, 20 gold claims, and a share of Lobengula's cattle. This was in return for fighting in a war against Matabeleland. Lobengula wrote to Queen Victoria again. He tried to send Mshete to England again. But Loch held the izinDuna at Cape Town for a few days, then sent them home.

After a few small fights, the First Matabele War began in October. Company troops moved on Lobengula. They used their powerful Maxim machine guns to defeat attacks by the much larger Matabele army. On 3 November, as the white soldiers neared Bulawayo, Lobengula burned the town and fled. The settlers began rebuilding on the ruins the next day. Jameson sent troops north from Bulawayo to bring the king back. But this group stopped their chase in early December. This was after the rest of Lobengula's army attacked and destroyed 34 soldiers who had crossed the Shangani River ahead of the main force. Lobengula escaped the Company, but he lived only two more months. He died from smallpox in the north of the country on 22 or 23 January 1894.

Matabeleland was conquered. The Matabele izinDuna all agreed to peace with the Company in late February 1894. Rhodes later paid for the education of three of Lobengula's sons. Many early settlers called the Company's land "Rhodesia." This name became official in May 1895 by the Company, and in 1898 by Britain. The lands south of the Zambezi were called "Southern Rhodesia." Those to the north were divided into North-Western and North-Eastern Rhodesia. These merged to form Northern Rhodesia in 1911.

For 30 years under Company rule, railways, telegraph wires, and roads were built. Thousands of white colonists moved in. Important mining and tobacco farming industries were created. However, this partly changed the traditional ways of life for the black population. Western-style buildings, government, religion, and economy disrupted their lives. Southern Rhodesia, which attracted most settlers and money, started making a profit by 1912. Northern Rhodesia, however, lost millions for the Company until the 1920s. After a vote in 1922, Southern Rhodesia gained responsible government from Britain in 1923. It became a self-governing colony. Northern Rhodesia became a British protectorate the next year.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |