Progress facts for kids

Progress means moving towards a better, more improved, or desired state. When people talk about "progress," they often mean that advancements in technology, science, and how society is organized have made life better for humans. They also believe these advancements will continue to improve our lives. This can happen because people actively work for change, like through social projects or activism, or as a natural part of how societies change over time.

The idea of progress became popular in the early 1800s, especially in social theories about how cultures evolve. Thinkers during the Age of Enlightenment also discussed this idea. Many different political groups have supported social progress, but they often have different ideas about how to achieve it.

Contents

How Do We Measure Progress?

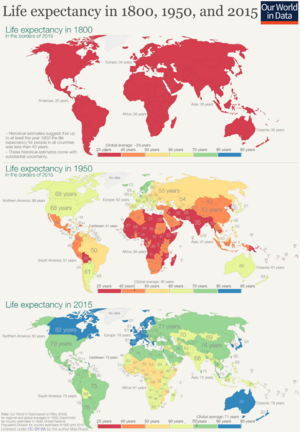

We can measure progress using different signs. These can include economic information, new inventions, changes in political or legal systems, and things that affect individual lives, like how long people live or their risk of getting sick.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth is often used to see how well a country is doing. It's a key number politicians often use to show their success. However, GDP has some problems as a way to measure true progress, especially for developed countries. For example, it doesn't consider damage to the environment or if economic activities can continue for a long time without harming the future.

Wikiprogress is a website set up to share information about how to measure society's progress. It helps people exchange ideas and knowledge. HumanProgress.org is another online place that collects data on different ways to measure how society is improving.

Our World in Data is an online publication from the University of Oxford. It studies how we can make progress against big global problems like poverty, disease, hunger, climate change, war, and inequality. Their goal is to share "research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems."

The Social Progress Index is a tool that measures how well countries meet the social and environmental needs of their citizens. It uses 52 different indicators in three main areas: Basic Human Needs, Foundations of Wellbeing, and Opportunities. These indicators show how well different countries are performing.

Here are some other ways progress can be measured:

- Broad measures of economic progress

- Disability-adjusted life year

- Green national product

- Gender-related Development Index

- Genuine Progress Indicator

- Gross National Happiness

- Gross National Well-being

- Happy Planet Index

- Human Development Index

- Legatum Prosperity Index

- Social Progress Index

- OECD Better Life Index

- Subjective life satisfaction

- Where-to-be-born Index

- Wikiprogress

- World Happiness Report

- World Values Survey

Progress in Science

Scientific progress is the idea that scientists learn more over time. This leads to a growing collection of scientific knowledge. For example, chemists in the 19th century knew less about chemistry than chemists in the 20th century. And 20th-century chemists knew less than chemists today. We expect that chemists in the future will know even more.

From the 1700s to the late 1900s, the history of science was often seen as a steady build-up of knowledge. True theories replaced old, false beliefs. However, some newer ideas, like those from Thomas Kuhn, suggest that science history involves different ideas or "paradigms" competing with each other. These ideas are also influenced by intellectual, cultural, economic, and political trends. Some people disagree with this view, saying it makes scientific progress seem messy and not truly progressive.

It's debated whether other subjects, like history or philosophy, make progress in the same way as science. For instance, today's historians know more about global history than ancient historians like Herodotus. But knowledge can also be lost over time, or what we consider important to know can change.

Social Progress and Fairness

Condorcet, a French thinker, described social progress as including things like the end of slavery, more people learning to read and write (literacy), less inequality between genders, improvements in prisons, and a decrease in poverty. We can measure a society's social progress by how well it meets basic human needs, helps citizens improve their quality of life, and provides opportunities for everyone to succeed.

Social progress often improves when a country's GDP increases. However, other factors are important too. If economic growth and social progress are out of balance, it can slow down further economic progress and even lead to political problems. When social progress lags behind economic growth, political instability and unrest often happen. This also holds back economic growth in countries that don't meet human needs, build strong communities, or create opportunities for their people.

Women's Rights and Progress

Historians have long studied how progress improved the status of women in traditional societies. This topic became important during the Enlightenment and continues today. Thinkers like William Robertson and Edmund Burke in Britain connected ideas about beauty, taste, and morality to the needs of modern societies. They looked at how women were treated in "savage" versus "civilized" societies. This helped shape the idea that the changing role of women was central to modern European civilization.

Experts on ancient history have found that women in the Roman Empire had a somewhat better standing than in ancient Greece. This was because the Roman Empire had better social organization, peace, and laws. In traditional China, women often had a lower status. This led some Chinese reformers in the early 20th century to believe that progress meant completely rejecting old traditions.

Historians Leo Marx and Bruce Mazlish noted that the status of women has "improved markedly" in cultures that adopted the Enlightenment idea of progress.

How Societies Change (Modernization)

Modernization was promoted by classical liberals in the 1800s and 1900s. They wanted to quickly update economies and societies to remove old obstacles to free markets and the free movement of people. During the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, thinkers began to realize that people themselves could change society and their way of life. Instead of believing everything was controlled by gods, people started to think that they made their own society. And because they made it, they could also fully understand it. This led to new sciences that aimed to provide knowledge about society and how to make it better.

This new way of thinking led to progressive ideas, which were different from conservative ones. Social conservatives were doubtful about quick fixes for society's problems. They believed that trying to completely remake society usually made things worse. Edmund Burke was a famous supporter of this view. Later, liberals like Friedrich Hayek shared similar ideas. They argued that society changes naturally, and big plans like the French Revolution or Communism hurt society by removing traditional limits on power.

Scientific discoveries in the 1500s and 1600s influenced thinkers like Francis Bacon, who wrote "New Atlantis." In the 1600s, Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle said that each new age benefits from not having to rediscover what earlier ages already achieved. The ideas of John Locke also supported this and were spread by thinkers like Diderot and Condorcet. Locke greatly influenced the American Founding Fathers. The first full explanation of progress came from Turgot in 1750. For Turgot, progress included not just arts and sciences, but also culture, manners, laws, economy, and society. Condorcet predicted the end of slavery, more literacy, less gender inequality, prison reforms, and less poverty.

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) believed that ideas and education could improve human nature. For those who don't share this belief, the idea of progress becomes less certain.

Alfred Marshall (1842–1924), a British economist, was a supporter of classical liberalism. He was very interested in human progress and what we now call sustainable development. For Marshall, wealth was important because it could improve the physical, mental, and moral health of people. After World War II, many modernization programs in developing countries were based on the idea of progress.

Progress in Different Countries

In Russia, the idea of progress was first brought from the West by Peter the Great (1672–1725). He used it to modernize Russia and make his rule seem right. By the early 1800s, Russian thinkers adopted the idea, but the tsars (emperors) no longer fully accepted it. Four main ideas about progress appeared in 19th-century Russia: conservative, religious, liberal, and socialist. The socialist idea, in the form of Bolshevism, eventually won out.

The leaders of the American Revolution, like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams, were influenced by Enlightenment ideas. They believed progress meant they could create a political system that would benefit everyone. Adams famously wrote that he studied politics and war so that future generations could study mathematics, philosophy, and arts, leading to a better society.

Juan Bautista Alberdi (1810–1884) was an important political thinker in Argentina. He believed economic freedom was key to progress. He encouraged faith in progress but warned Latin Americans against simply copying American and European models. He hoped for progress through immigration, education, and a moderate form of government.

In Mexico, José María Luis Mora (1794–1850) was a leader of classical liberalism after independence. He fought against the power of the army, church, and large landowners. He saw progress as human development through seeking truth and as bringing wealth through new technology. His plan for Mexico included a republican government, widespread public education free from church control, selling church lands, and government control over a smaller military. He also wanted legal equality for native Mexicans and foreign residents. His ideas became key parts of the Mexican Constitution of 1857.

In Italy, the idea that scientific and technological progress would solve human problems was linked to the nationalism that united the country in 1860. The Prime Minister, Camillo Cavour, saw railways as vital for modernizing and uniting Italy. After Italy was formed in 1861, the government worked to speed up modernization and industrialization, especially in the poorer southern regions. They also focused on public education to fight illiteracy and improve health.

In China, the Nationalist party (Kuomintang) in the 20th century supported progress. Later, the Communists under Mao Zedong adopted Western models, but their projects led to huge famines. After Mao's death, the new leaders, like Deng Xiaoping, strongly promoted modernizing the economy using capitalist ideas and Western technology. This was called the "Opening of China."

Among environmentalists, there are different views. Some are optimistic and believe that new designs, social ideas, and green technologies can solve environmental problems. This is called bright green environmentalism. Others are more pessimistic about technology. They warn of coming global crises like climate change and tend to reject the idea of modernity and progress. For example, Kirkpatrick Sale wrote that progress is a myth that only benefits a few, and that environmental disaster is coming. This view is similar to Deep Ecology.

Different Ideas About Progress

Sociologist Robert Nisbet said that "No single idea has been more important than ... the Idea of Progress in Western civilization for three thousand years." He listed five key beliefs of progress:

- The value of the past.

- The greatness of Western civilization.

- The importance of economic and technological growth.

- Faith in reason and scientific knowledge.

- The importance and value of life on Earth.

Sociologist P. A. Sorokin believed that ancient Chinese, Babylonian, Hindu, Greek, and Roman thinkers, who saw social changes as cycles or without a clear direction, were closer to reality than modern thinkers who see progress as a straight line forward. Unlike Confucianism and Taoism, which look for an ideal past, the Judeo-Christian-Islamic traditions believe history has a purpose. This idea was later turned into the concept of progress in modern times. This is why Chinese supporters of modernization have looked to Western models.

Philosopher Karl Popper said that progress wasn't a complete scientific explanation for social events. More recently, Kirkpatrick Sale, who is a neo-luddite (someone who dislikes new technology), wrote that progress is just a myth.

Iggers (1965) said that those who supported progress didn't fully understand how destructive and irrational humans could be. On the other hand, critics of progress misunderstood the role of reason and morality in human behavior.

In 1946, psychoanalyst Charles Baudouin said that modern society still believes the present is better than the past, even while claiming to have given up on the "myth of progress." He argued that people stopped believing in progress but started believing in things that were once just tools for progress. He felt that believing the present is better than the past is only true if you believe in the myth of progress.

Oswald Spengler (1880–1936), a German historian, believed in a cyclical theory of history, where civilizations rise and fall. His book, The Decline of the West, was written in 1920. World War I, World War II, and the rise of totalitarian governments showed that progress wasn't automatic. They proved that technological improvements didn't always lead to democracy or moral improvement. British historian Arnold J. Toynbee (1889–1975) thought that Christianity could help modern civilization overcome its challenges.

The Jeffersonians (followers of Thomas Jefferson) believed that history wasn't finished and that people could start fresh in a new world. They took the idea of progress and made it more American by connecting it to the well-being of ordinary people. They believed people could control their own future and that virtue was important for a republic. They cared about happiness, progress, and wealth.

Historian J. B. Bury wrote in 1920:

To the minds of most people the desirable outcome of human development would be a condition of society in which all the inhabitants of the planet would enjoy a perfectly happy existence....It cannot be proved that the unknown destination towards which man is advancing is desirable. The movement may be Progress, or it may be in an undesirable direction and therefore not Progress..... The Progress of humanity belongs to the same order of ideas as Providence or personal immortality. It is true or it is false, and like them it cannot be proved either true or false. Belief in it is an act of faith.

In postmodernist thought, which became popular from the 1980s, the big claims of modernizers were questioned. The very idea of social progress was re-examined. In this new view, radical modernizers like Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong were seen as dictators whose idea of social progress was deeply flawed. Postmodernists question the ideas of progress from the 1800s and 1900s, from both capitalist and Marxist viewpoints. They argue that both capitalism and Marxism focus too much on technology and money, ignoring inner happiness and peace of mind. Postmodernism suggests that perfect societies (utopias) and terrible societies (dystopias) are actually very similar, both being grand stories with impossible endings.

Some 20th-century writers refer to the "Myth of Progress." This means the idea that the human condition will always get better. In 1932, English doctor Montague David Eder wrote: "The myth of progress states that civilization has moved, is moving, and will move in a desirable direction. Progress is inevitable..." Eder argued that advances in civilization were actually leading to more unhappiness and less control over the environment. Some strong critics of progress say it's still a powerful idea today. British historian John N. Gray (born 1948) concluded:

Faith in the liberating power of knowledge is encrypted into modern life. Drawing on some of Europe's most ancient traditions, and daily reinforced by the quickening advance of science, it cannot be given up by an act of will. The interaction of quickening scientific advance with unchanging human needs is a fate that we may perhaps temper, but cannot overcome... Those who hold to the possibility of progress need not fear. The illusion that through science humans can remake the world is an integral part of the modern condition. Renewing the eschatological hopes of the past, progress is an illusion with a future.

Recently, the idea of progress has been linked to psychology. It's seen as "what helps you move towards the end result of a specific goal."

Old Ideas About Progress

Historian J. B. Bury said that ancient Greek thought often focused on ideas of world-cycles or eternal return. They also believed in a "Golden Age" of innocence that came before, similar to the idea of the "fall of man" in Judaism. Time was often seen as something that made the world worse. Bury gave credit to the Epicureans for having ideas that could lead to a theory of progress. They believed in atomism (the idea that everything is made of tiny particles) and a world without a god interfering.

For them, the earliest condition of men resembled that of the beasts, and from this primitive and miserable condition they laboriously reached the existing state of civilisation, not by external guidance or as a consequence of some initial design, but simply by the exercise of human intelligence throughout a long period.

Robert Nisbet and Gertrude Himmelfarb also said that other Greeks had a notion of progress. Xenophanes said: "The gods did not reveal to men all things in the beginning, but men through their own search find in the course of time that which is better."

The Renaissance (1400s-1600s)

During the Middle Ages, science was largely based on Scholastic (a way of thinking from the Middle Ages) interpretations of Aristotle's work. The Renaissance, from the 1400s to the 1600s, changed thinking in Europe towards a more experimental view, based on Plato's ideas. This sparked a revolution in curiosity about nature and scientific advancement, which then led to technical and economic progress. People also started to see individual potential as an endless journey towards becoming more like God, which paved the way for the idea of humans being able to achieve unlimited perfection and progress.

The Enlightenment (1650–1800)

In the Enlightenment, French historian and philosopher Voltaire (1694–1778) was a strong supporter of progress. He believed that science and reason were the main forces driving society forward.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) argued that progress is not automatic or continuous. It doesn't just mean more knowledge or wealth. Instead, it's a difficult and often accidental journey from a rough state to a civilized one, moving towards an enlightened culture and the end of war. Kant called for education, seeing the education of humanity as a slow process where world history pushes people towards peace through wars, international trade, and people acting in their own enlightened self-interest.

Scottish thinker Adam Ferguson (1723–1816) saw human progress as part of a divine plan. He believed that life's difficulties and dangers pushed humans to develop. The unique human ability to evaluate things led to ambition and the desire for excellence. He thought humans were always striving, and found happiness only in effort.

Some scholars believe that the idea of progress, which became strong during the Enlightenment, was a way of making early Christianity's ideas more worldly, and also a new take on ideas from ancient Greece.

Romanticism and the 1800s

In the 1800s, Romantic critics argued that progress didn't automatically make life better. In some ways, it could make things worse. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) disagreed with the idea of progress because he thought that differences in people's situations were "the best (state) calculated to develop the energies and faculties of man." He believed that if population and food grew at the same rate, humans might never have left a "savage state." He argued that human improvement was shown by the growth of intellect, which helped balance the problems caused by population growth.

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) criticized the idea of progress as a "weakling's doctrine of optimism." He wanted to challenge beliefs like faith in progress, so that strong individuals could rise above the common people. A key part of his thinking was using the ancient idea of "eternal recurrence" (things happening over and over) to challenge the idea of progress.

Iggers (1965) said that in the late 1800s, most people agreed that progress came from a steady increase in knowledge. They believed that scientific ideas were replacing religious or philosophical ones. Most scholars concluded that this growth in scientific knowledge led to the growth of industry and changed warlike societies into industrial and peaceful ones. They also agreed that governments were becoming less controlling, and there was more freedom and rule by consent. There was more focus on large social and historical forces, and progress was increasingly seen as something that happened naturally within society.

Marxist Theory (Late 1800s)

Karl Marx developed a theory called historical materialism. He described the mid-1800s as a time when:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty, and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all which is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.

Marx also described how social progress happens, which he believed was based on how productive forces (like tools and technology) and production relations (how people organize work) interact:

No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.

Marx saw Capitalism as a process of constant change, where growing markets break down all fixed parts of human life. He argued that capitalism is progressive and not against change. Marxism also states that capitalism, in its search for higher profits and new markets, will eventually lead to its own downfall. Marxists believe that in the future, capitalism will be replaced by socialism and eventually communism.

Many supporters of capitalism, like Joseph Schumpeter, agreed with Marx's idea that capitalism is a process of constant change through "creative destruction" (where old ways are destroyed to make way for new ones). However, unlike Marx, they believed and hoped that capitalism could continue forever.

So, by the early 1900s, two opposing ideas—Marxism and liberalism—both believed that continuous change and improvement were possible and desirable. Marxists strongly opposed capitalism, and liberals strongly supported it. But they both agreed on the idea of progress, which says that humans have the power to make, improve, and reshape their society using scientific knowledge, technology, and practical experiments. Modernity refers to cultures that embrace this idea of progress. (This is different from modernism, which was an artistic and philosophical movement that sometimes embraced technology but often rejected individualism or modernity itself.)

See also

In Spanish: Progreso social para niños

In Spanish: Progreso social para niños

- Accelerating change

- Constitutional economics

- Frontierism

- Fordism

- Global social change research project

- Happiness economics

- High modernism

- Leisure satisfaction

- Manifest Destiny

- Money-rich, time-poor

- Moral progress

- New Frontier

- Progressive utilization theory

- Psychometrics

- Social development

- Social change

- Social justice

- Social order

- Social regress

- Sociocultural evolution

- Scientism

- Technocentrism

- Technological progress

- Techno-progressivism