Southern Cross Expedition facts for kids

The Southern Cross Expedition was the first British trip to Antarctica during a time called the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. It happened before the more famous journeys of explorers like Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. This expedition was the idea of Carsten Borchgrevink, an explorer from Norway and England.

This trip was special for many reasons:

- It was the first time anyone spent a whole winter on the Antarctic mainland.

- It was the first time explorers visited the Great Ice Barrier (now called the Ross Ice Shelf) since Sir James Clark Ross explored it in the 1840s.

- It was the first time anyone landed on the surface of the Great Ice Barrier.

- It was also the first time dogs and sledges were used for travel in Antarctica.

Sir George Newnes, a British magazine publisher, paid for the expedition. Borchgrevink's team sailed on a ship called the Southern Cross. They spent the winter of 1899 at Cape Adare, which is on the coast of the Ross Sea. There, they did many scientific studies. However, exploring inland was hard because of the mountains and ice around their base.

In January 1900, the team left Cape Adare on the Southern Cross. They explored the Ross Sea, following the same path Ross took 60 years earlier. They reached the Great Ice Barrier. A small team of three people made the first sledge journey on the Barrier's surface. They set a new record for the Farthest South point ever reached, at 78° 50′S.

When the expedition returned to Britain, it was not welcomed warmly by the geographical experts in London. They were planning their own big Antarctic trip and felt Borchgrevink had gone ahead of them. People also questioned Borchgrevink's leadership and said the scientific results were not enough. Because of this, Borchgrevink never became as famous as Scott or Shackleton. His expedition was soon forgotten compared to the exciting stories of other explorers. However, Roald Amundsen, who was the first to reach the South Pole in 1911, said that Borchgrevink's expedition had removed the biggest challenges for Antarctic travel. He said it opened the way for all the expeditions that followed.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Adventure

Carsten Borchgrevink was born in Norway in 1864. His father was Norwegian, and his mother was English. In 1888, he moved to Australia and worked as a land surveyor. Later, he became a schoolteacher.

Borchgrevink loved adventure. In 1894, he joined a whaling trip that went into Antarctic waters. They reached Cape Adare, which is at the entrance to the Ross Sea. Borchgrevink and some others briefly landed there. They believed they were the first people to step on the Antarctic continent. (Though an American sealer named John Davis thought he had landed in Antarctica in 1821.)

Borchgrevink was sure that Cape Adare would be a great base for an expedition. It had a huge penguin colony, which meant plenty of fresh food and fat for fuel. He thought a future team could stay there for the winter and then explore the inside of Antarctica.

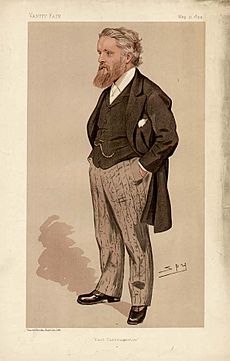

After his trip to Cape Adare, Borchgrevink spent years trying to find money for an Antarctic expedition. He gave a speech in London in 1895, saying he was ready to lead such a trip. But he didn't have much luck at first. The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) was planning its own big trip, the Discovery Expedition (1901–04). The RGS president, Sir Clements Markham, saw Borchgrevink as a foreigner getting in the way of their plans.

But Borchgrevink managed to convince Sir George Newnes, a publisher, to pay for his whole expedition. Newnes paid about £40,000, which was a lot of money back then. This made Markham and the RGS very angry. Newnes asked that Borchgrevink's expedition sail under the British flag and be called the "British Antarctic Expedition." Borchgrevink agreed, even though only two people on his whole team were British.

What the Expedition Hoped to Do

Borchgrevink's main goals for the expedition were scientific and geographical discovery. He also hoped to find new places and make long journeys, maybe even try to reach the South Pole. However, he didn't know yet that their base at Cape Adare would make it hard to explore deep into Antarctica.

The Ship: Southern Cross

For the expedition, Borchgrevink bought a steam whaling ship in 1897. It was built in Norway in 1886 and was named Pollux. Borchgrevink renamed it the Southern Cross. The ship was designed by Colin Archer, who also designed Fridtjof Nansen's famous ship, Fram. The Fram had safely returned from its long journey in the Arctic.

The Southern Cross was a strong ship, 146 feet (44.5 meters) long. It was fitted with special engines for the trip. Even though some people doubted it, the ship did everything it needed to do in the icy Antarctic waters. Sadly, like many old polar ships, it didn't last long after the expedition. It was sold and later sank in 1914, taking all 173 people on board with it.

The Team Members

The team that stayed on land at Cape Adare had ten men. This included Borchgrevink, five scientists, a doctor, a cook, and two dog drivers. Five of them, including Borchgrevink, were Norwegian. Two were English, one was Australian, and the two dog experts were from northern Norway, sometimes called Lapps or "Finns."

One of the scientists was Louis Bernacchi from Tasmania. He studied magnetism and weather. He had planned to join another Antarctic expedition but couldn't. So, he traveled to London and got a spot on Borchgrevink's team.

Bernacchi later wrote about the expedition. He criticized Borchgrevink's leadership but defended the team's scientific achievements. In 1901, Bernacchi went back to Antarctica on Scott's Discovery expedition. Another man from Borchgrevink's team, William Colbeck, also helped Scott's expedition later.

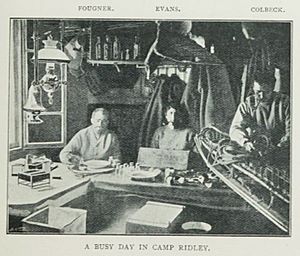

The assistant zoologist was Hugh Blackwell Evans, who had lived on a cattle ranch in Canada. The main zoologist was Nicolai Hanson, a university graduate. The expedition's doctor was Herluf Kløvstad. Other team members included Anton Fougner (scientific assistant), Kolbein Ellifsen (cook), and the two young Sami dog handlers, Per Savio and Ole Must.

The ship's crew had 19 Norwegian officers and sailors, plus one Swedish steward. The captain, Bernard Jensen, was very experienced in navigating icy waters in both the Arctic and Antarctic. He had been with Borchgrevink on an earlier trip in 1894–1895.

The Journey to Antarctica

Life at Cape Adare

The Southern Cross left London on August 23, 1898. Before leaving, the Duke of York (who later became King George V) inspected the ship and gave them a British flag. The ship carried 31 men and 90 Siberian sledge dogs. These were the first dogs ever taken on an Antarctic expedition. After getting more supplies in Hobart, Tasmania, the Southern Cross sailed for Antarctica on December 19.

The ship crossed the Antarctic Circle on January 23, 1899. After being stuck in pack ice for three weeks, they saw Cape Adare on February 16. They anchored close to the shore the next day.

Cape Adare was found by explorer James Clark Ross during his 1839–43 expedition. It has a large triangular beach area below a long point of land. This beach was where Borchgrevink and Bull had briefly landed in 1895. It had one of the biggest Adelie penguin colonies on the whole continent. Borchgrevink had noted in 1895 that there was plenty of space "for houses, tents and provisions." The many penguins would provide food and fuel for the winter.

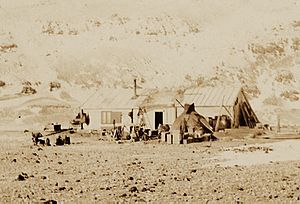

Unloading began on February 17. The dogs and their two Sami handlers, Savio and Must, were the first ashore. They stayed with the dogs and became the first people to spend a night on the Antarctic continent. Over the next twelve days, the rest of the equipment and supplies were brought ashore. Two huts were built: one for living and one for storage. These were the first buildings ever put up on the continent. A third small building was made from extra materials to observe magnetism. The living hut for ten men was small and crowded. Bernacchi later said it was "fifteen feet square, lashed down by cables to the rocky shore." The dogs lived in kennels made from packing cases. By March 2, the base, named "Camp Ridley" after Borchgrevink's mother, was ready. The Duke of York's flag was raised. That day, the Southern Cross left to spend the winter in Australia.

The living hut had a small room for developing photos and another for preparing animal specimens. Light came into the hut through a double-glazed window and a small pane high on the northern wall. Bunks were built around the walls, and a table and stove were in the middle. During the last few weeks of Antarctic summer, the team practiced traveling with dogs and sledges on the sea ice. They also mapped the coastline, collected birds and fish, and hunted seals and penguins for food and fuel. By mid-May, winter began, and outdoor activities mostly stopped.

The Antarctic Winter

Winter was a difficult time. Bernacchi wrote that people became bored and easily annoyed. He said, "Officers and men, ten of us in all, found tempers wearing thin." During this time, Borchgrevink's weaknesses as a leader became clear. Bernacchi said he was "in many respects... not a good leader." Explorer Ranulph Fiennes later described the conditions as "democratic anarchy," meaning there was a lot of dirt, mess, and not much activity.

Borchgrevink wasn't trained in science, and he found it hard to make simple observations. Still, the team kept up their scientific studies all winter. When the weather allowed, they exercised outside the hut. Savio even built a sauna in the snow for fun. They also held concerts with lantern slides, songs, and readings.

There were two dangerous incidents during the winter. Once, a candle left burning by a bunk set the hut on fire, causing a lot of damage. Another time, three men almost died from coal fire fumes while they slept.

The team had plenty of basic food like butter, tea, coffee, fish, cheese, soup, and vegetables. But some complained about not having enough treats. Colbeck noted that "all the tinned fruits supplied for the land party were either eaten on the passage or left on board for the [ship's] crew." There was also a shortage of tobacco.

The zoologist, Nicolai Hanson, became sick during the winter. He died on October 14, 1899, likely from a stomach problem. He was the first person to be buried on the Antarctic continent. His grave was made by blasting a hole in the frozen ground at the top of Cape Adare. Bernacchi wrote: "There amidst profound silence and peace, there is nothing to disturb that eternal sleep except the flight of seabirds." Hanson left behind a wife and a baby daughter he had never met.

As winter ended and spring began, the team got ready for longer journeys using dogs and sledges. But their camp was blocked from the continent's interior by high mountains. Journeys along the coast were dangerous because the sea ice was not safe. These problems greatly limited their exploration. They mostly stayed near Robertson Bay. Here, they found a small island and named it Duke of York Island after the expedition's supporter.

Exploring the Ross Sea

On January 28, 1900, the Southern Cross returned. Borchgrevink and his team quickly left the camp. On February 2, he took the ship south into the Ross Sea. Two years later, members of the Discovery Expedition visited Cape Adare. Edward Wilson wrote that Borchgrevink's team had left in a hurry and left behind "heaps of refuse all around, and a mountain of provision boxes, dead birds, seals, dogs, sledging gear... and heaven knows what else."

The Southern Cross first stopped at Possession Island. There, they found the tin box that Borchgrevink and Bull had left in 1895. Then, they sailed south along the Victoria Land coast. They found more islands, and Borchgrevink named one after Sir Clements Markham, even though Markham had been unfriendly towards the expedition.

Next, the Southern Cross sailed to Ross Island. They saw the volcano Mount Erebus and tried to land at Cape Crozier, near Mount Terror. Here, Borchgrevink and Captain Jensen were almost drowned by a huge wave. This wave was caused by a large piece of ice breaking off the nearby Great Ice Barrier.

Following the path of James Clark Ross from sixty years before, they sailed east along the edge of the Barrier. They found the inlet where Ross had reached his farthest south point in 1843. Their observations showed that the Barrier's edge had moved about 30 miles (50 km) south since Ross's time. This meant their ship was already south of Ross's record. Borchgrevink wanted to land on the Barrier itself. Near Ross's inlet, he found a spot where the ice sloped enough for a landing.

On February 16, Borchgrevink, Colbeck, and Savio landed with dogs and a sledge. They climbed onto the Barrier's surface and traveled a few miles south. They calculated their position as 78°50′S, which was a new Farthest South record. They were the first people to travel on the Barrier's surface. Amundsen later praised them, saying: "We must acknowledge that, by ascending the Barrier, Borchgrevink opened the way to the south, and threw aside the greatest obstacle to the expeditions that followed." Ten years later, Amundsen would set up his base camp, "Framheim," near this same spot before his successful journey to the South Pole.

On its way north, the Southern Cross stopped at Franklin Island, off the Victoria Land coast. They made many magnetic measurements. These showed that the South Magnetic Pole was in Victoria Land, as expected, but further north and west than thought before. The team then sailed for home, crossing the Antarctic Circle on February 28. On April 1, news of their safe return was sent by telegram from Bluff, New Zealand. The dogs were left on Native Island, New Zealand. Many dogs were killed due to rules about animal movement, but a few remained. Ernest Shackleton later bought 9 of these dogs.

What Happened After

The Southern Cross returned to England in June 1900. The welcome was not very warm. People were more interested in the upcoming Discovery Expedition, which was set to sail the next year.

Borchgrevink, however, said his trip was a great success. He believed the Antarctic regions could be like another Klondyke, meaning there were good chances for fishing, sealing, and finding minerals. He had proven that an expedition could survive an Antarctic winter. He had also made several new discoveries. These included new islands in Robertson's Bay and the Ross Sea, and the first landings on Franklin Island, Coulman Island, Ross Island, and the Great Ice Barrier. He also mapped the Victoria Land coast and found the "Southern Cross Fjord" and a good camping spot near Mount Melbourne.

Borchgrevink thought his most important achievement was climbing onto the Great Ice Barrier and traveling to "the furthest south ever reached by man."

Borchgrevink's book about the expedition, First on the Antarctic Continent, was published the next year. The English version was criticized for being too much like a newspaper story and for sounding boastful. Borchgrevink, who was "not known for either his modesty or his tact," went on a lecture tour, but he didn't get a good reception.

Even though many of Hanson's scientific notes disappeared, Hugh Robert Mill called the expedition "interesting as a dashing piece of scientific work." The team had recorded weather and magnetic conditions in Victoria Land for a whole year. They had calculated the location of the South Magnetic Pole (though they didn't visit it). They also collected samples of Antarctica's animals, plants, and rocks. Borchgrevink also claimed to have found new insect and shallow-water animal species.

The geographical groups in Britain and other countries were slow to officially recognize the expedition. The Royal Geographical Society gave Borchgrevink a fellowship, and he later received other medals and honors from Norway, Denmark, and the United States. But the expedition's achievements were not widely known. Markham continued to describe Borchgrevink as tricky and without principles. Amundsen's warm praise was one of the few positive voices.

A late recognition came in 1930, long after Markham had died. The Royal Geographical Society gave Borchgrevink its Patron's Medal. They admitted that "justice had not been done at the time to the pioneer work of the Southern Cross expedition." They also said that the huge difficulties the expedition had overcome were not fully appreciated before. After the expedition, Borchgrevink lived a quiet life, mostly out of the public eye. He died in Oslo on April 21, 1934.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |