Stanislavski's system facts for kids

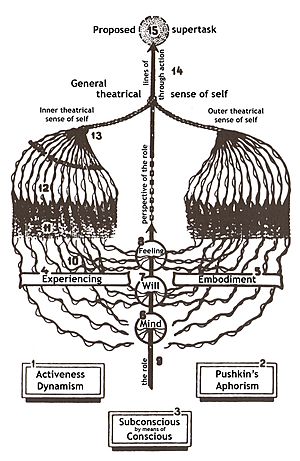

Stanislavski's system is a special way to train actors. It was created by a Russian theatre practitioner named Konstantin Stanislavski in the early 1900s. His system helps actors truly "experience" their roles. This means actors use their conscious thoughts and will to bring out deeper feelings and subconscious actions. When rehearsing, actors look for inner reasons for their character's actions. They also figure out what their character wants to achieve at any moment, which is called a "task."

Later, Stanislavski added more to his system. He focused on physical actions in rehearsals. This became known as the "Method of Physical Action." Instead of just talking about the play, he encouraged actors to improvise scenes. Stanislavski believed that "the best analysis of a play is to take action in the given circumstances."

Stanislavski's ideas became very popular around the world. Many acting teachers, who were his former students, helped spread his system. His writings were translated into many languages. His ideas are now so common that many actors use them without even knowing where they came from.

Contents

Stanislavski's Early Theatre Work

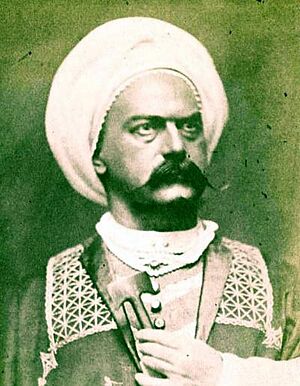

Stanislavski was an amateur actor and director until he was 33. In 1898, he co-founded the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. They wanted to change how plays were staged. Before the MAT, acting was often not very good in Russia. Actors sometimes didn't even learn their lines. They would stand at the front of the stage and speak loudly to the audience. They rarely talked directly to other actors.

Stanislavski's first successful plays were made without his system. He planned everything in detail beforehand, like how each role would be played and where actors would stand. He also started having discussions with the cast to analyze the play. This approach brought success, especially with his realistic plays by Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky. However, Stanislavski was still not happy.

His work on Chekhov's plays helped him develop the idea of subtext (hidden meanings). His experiments with Symbolism made him pay more attention to "inner action." He started focusing on the actor's process and teaching methods. He opened theatre studios, which were like laboratories. Here, he could try out new ways to train actors and experiment with new theatre styles.

Throughout his career, Stanislavski always thought deeply about his acting and directing. His system grew from his efforts to overcome problems he faced in his own performances. A big turning point was a crisis he had in 1906.

Stanislavski eventually put his techniques into a clear, systematic method. It combined ideas from three main influences:

- The Meiningen company, which focused on a director-led, unified, and disciplined approach.

- The Maly Theatre, which focused on realistic acting.

- The realistic staging of Antoine and the independent theatre movement.

Stanislavski first mentioned his system in 1909. That same year, he used it in rehearsals for Ivan Turgenev's play A Month in the Country. Some actors, like Olga Knipper, didn't like being part of his experiments. But Stanislavski insisted, and the MAT officially adopted his system in 1911.

Experiencing a Role as an Actor

A rediscovery of the 'system' must begin with the realization that it is the questions which are important, the logic of their sequence and the consequent logic of the answers. A ritualistic repetition of the exercises contained in the published books, a solemn analysis of a text into bits and tasks will not ensure artistic success, let alone creative vitality. It is the Why? and What for? that matter and the acknowledgement that with every new play and every new role the process begins again.

—Jean Benedetti, acting teacher and Stanislavski's biographer.

Stanislavski's system is about "experiencing a role." This means that as an actor, you should feel things similar to what your character feels. You should do this "each and every time you do it." Stanislavski agreed with actor Tommaso Salvini, who said actors should truly feel what they show, "be it the first or the thousandth" performance.

However, not all emotions are right. The actor's feelings must match the character's experience. Stanislavski saw Salvini as the best example of "experiencing." Salvini believed actors should feel emotions during the actual performance. Another actor, Cocquelin, thought emotions were only for rehearsals.

Stanislavski called his method the "art of experiencing." He compared it to the "art of representation" (where feelings are only for practice) and "hack" acting (where feelings are not used at all). For Stanislavski, "experiencing" means playing "credibly." This means thinking, wanting, and behaving truthfully, like a real human. The actor should feel "as one with" the role.

Stanislavski's method tries to make the actor's will create new things. It also tries to activate subconscious processes indirectly. This helps actors create the inner, psychological reasons for a character's behavior. Stanislavski knew that most performances mix these styles. But he felt "experiencing" should be the main one.

Many years of work led to the exercises that help actors "experience the role." Some of these ideas can be seen in a letter Stanislavski wrote in 1905. He advised Vera Kotlyarevskaya on playing Charlotta in Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard:

- "First, live the role without messing up the words."

- "Imagine Charlotta is engaged. How would she act?"

- "Or, she's fired but finds work in a circus. How does she do gymnastics?"

- "Try different hairstyles and find things in yourself that remind you of Charlotta."

- "Make this German woman speak Russian and notice her speech."

- "Play Charlotta in a dramatic moment. Try to make her cry sincerely."

These exercises help actors prepare for a performance based on experiencing the role. "Experiencing" is the inner, psychological part of a role. It uses the actor's own feelings and personality. Stanislavski believed creating this inner life should be the actor's first goal. He called these training exercises "psychotechnique."

Given Circumstances and the Magic If

When I give a genuine answer to the if, then I do something, I am living my own personal life. At moments like that there is no character. Only me. All that remains of the character and the play are the situation, the life circumstances, all the rest is mine, my own concerns, as a role in all its creative moments depends on a living person, i.e., the actor, and not the dead abstraction of a person, i.e., the role.

Stanislavski's "Magic If" is about imagining yourself in a fictional situation. You think about what you would do if you were really in those circumstances. These circumstances are "given" to the actor by the playwright, director, or other actors. All these details that an actor must use are called the "given circumstances." It's important not to just play yourself. Instead, you put yourself into the character's circumstances.

Actors create imaginary details, like sensory feelings, during preparation and rehearsal. This helps them have a natural, subconscious reaction during the performance. These "inner objects of attention" help create an "unbroken line" of experiencing. This is the inner life of the role. An "unbroken line" means the actor stays focused on the play's fictional world. They don't get distracted by the audience or real-world worries. At first, this "line" might be broken, but it becomes stronger with practice.

When an actor is fully "experiencing" the role, they are completely absorbed in the play. This state is like what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls "flow." Stanislavski called it "I am being." He encouraged this focus by teaching "public solitude" and "circles of attention." These ideas came from meditation techniques like yoga. However, Stanislavski did not want actors to completely believe they were someone else. That would be unhealthy.

Tasks and Actions in Acting

Action is the very basis of our art, and with it our creative work must begin.

An actor's performance is driven by a series of "tasks." A task is a problem in the "given circumstances" of a scene that the character needs to solve. It's often asked as a question: "What do I need the other person to do?" or "What do I want?"

To prepare for a role, actors break their parts into small "bits." Each "bit" changes when a big discovery or decision alters the direction of the action. (Each "bit" or "beat" matches a single motivation or task.)

Stanislavski said a task must be exciting for the actor. It should make them want to act:

- "An actor's tasks must always get his feelings, will, and intelligence involved."

- "The task must help create excitement."

- "Like a magnet, it must pull you in and make you try hard."

- "The task is the reason for creative activity."

- "The task creates the inner reasons that turn into action."

- "The task is the heart of the bit, making the role come alive."

Stanislavski's play A Month in the Country (1909) was a big step in his artistic growth. It was the first play he produced using his system. He broke the MAT's tradition of open rehearsals and prepared this play in private. The cast started by discussing the "through-line" for their characters. This meant their emotional journey and how they change during the play. This production was the first time he analyzed the script's actions into small "bits."

Doing one task after another creates a "through-line of action." This connects all the small "bits" into a continuous experience. This "through-line" leads to a main task for the whole play, called a "supertask" or "superobjective." A performance combines the inner feelings of a role (experiencing) and its outer actions. Both are connected by working towards the supertask.

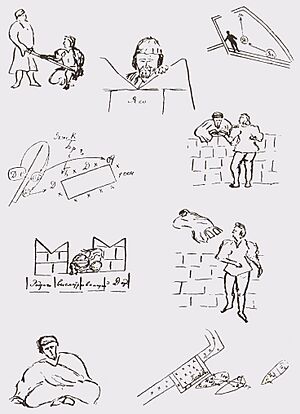

In his later work, Stanislavski focused more on conflicts in plays. He developed a rehearsal technique called "active analysis." In this, actors would improvise these conflicts. In American versions of Stanislavski's system, like in Uta Hagen's Respect for Acting, the things that stop a character from achieving their tasks are called "obstacles."

Method of Physical Action

Stanislavski further developed his system with a more physical way of rehearsing. After his death, this became known as the "Method of Physical Action." He had been working on it since 1916 and first used it practically in the early 1930s. The roots of this method go back to his early work as a director. He always focused on a play's actions. He also explored techniques with Vsevolod Meyerhold and the First Studio of the MAT before World War I. These included improvisation and breaking down scripts into "bits" and "tasks."

Many experts say the Method of Physical Action was a natural next step for Stanislavski. It wasn't a rejection of his earlier work. He first used this approach in rehearsals for Three Sisters and Carmen in 1934, and Molière in 1935.

He reduced discussions at the table. Instead, he encouraged "active analysis," where actors improvised the dramatic situations. Stanislavski believed, "The best analysis of a play is to take action in the given circumstances." He explained:

- "When an actor acts, they slowly gain control over the inner reasons for the character's actions."

- "This brings out the emotions and thoughts that caused those actions."

- "Then, an actor not only understands their part but also feels it."

- "That is the most important thing in creative stage work."

Stanislavski hoped to secure his final legacy by opening another studio in 1935. This was the Opera-Dramatic Studio, where the Method of Physical Action would be taught. This studio fully used the training exercises described in his books. Meanwhile, his earlier work, taught by students from his First Studio, was changing acting in the West. In the USSR, the MAT and Stanislavski's system became official models.

Many actors think his system is the same as the American Method. However, the American Method often focuses only on psychological techniques. Stanislavski's system is more complete. It explores character and action from both the "inside out" and the "outside in." It treats the actor's mind and body as connected. Stanislavski found that some students using "method acting" had mental problems. He encouraged his students to let go of the character after rehearsing.

Theatre Studios and Stanislavski's System

I may add that it is my firm conviction that it is impossible today for anyone to become an actor worthy of the time in which he is living, an actor on whom such great demands are made, without going through a course of study in a studio.

First Studio

The First Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) was a theatre studio Stanislavski created in 1898. He wanted to research and develop his system there. It was a place for teaching and experiments, away from the public. Stanislavski called a theatre studio "a laboratory for the experiments of more or less trained actors." Famous members of the First Studio included Yevgeny Vakhtangov, Michael Chekhov, Richard Boleslavsky, and Maria Ouspenskaya. They all greatly influenced the history of theatre.

Leopold Sulerzhitsky, Stanislavski's assistant, led the studio. He was nicknamed "Suler" by Maxim Gorky. The studio had an intense atmosphere, focusing on experimentation, improvisation, and self-discovery. Until his death in 1938, Suler taught early parts of Stanislavski's system. These included relaxation, concentration, imagination, communication, and emotion memory. In 1923, the company became independent from the MAT and renamed itself the Second Moscow Art Theatre. Stanislavski felt this was a betrayal of his ideas.

Opera Studio

Stanislavski's experience teaching and directing at his Opera Studio greatly influenced his system. He created it in 1918 under the Bolshoi Theatre. Stanislavski worked with his Opera Studio in his house. His brother and sister also helped teach there. It accepted young members from the Bolshoi and students from the Moscow Conservatory. Stanislavski also invited Serge Wolkonsky to teach diction and Lev Pospekhin to teach movement and dance.

Stanislavski wanted to combine the work of Mikhail Shchepkin and Feodor Chaliapin using his system. He hoped that if his system worked for opera, which is very traditional, it would prove his method was universal. From his Opera Studio experience, he developed his idea of "tempo-rhythm."

Between 1919 and 1922, Stanislavski gave 32 lectures to this studio. These were written down by Konkordia Antarova and published in 1939 as On the Art of the Stage. Pavel Rumiantsev, a student, documented the studio's activities until 1932. His notes were published as Stanislavski on Opera.

Opera—Dramatic Studio

Near the end of his life, Stanislavski created an Opera—Dramatic Studio in his apartment. Here, between 1935 and 1938, he taught a major course on his system in its final form.

Stanislavski wanted to make sure his legacy continued. In 1935, he decided to start a new studio. He wrote, "Our school will produce not just individuals, but a whole company." In June, he began teaching a group of teachers his system's training techniques and the Method of Physical Action. His wife, Lilina, also joined the teaching staff. Twenty students were accepted for the dramatic section of the Opera—Dramatic Studio. Classes began on November 15, 1935. One member was Mikhail Kedrov, who later became the artistic director of the MAT.

Jean Benedetti believes the course at the Opera—Dramatic Studio is "Stanislavski's true testament." Stanislavski planned a four-year study program focusing only on technique. The first two years covered material from An Actor's Work on Himself. The next two years covered An Actor's Work on a Role. Once students knew the training techniques, Stanislavski chose Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet for their work on roles. He insisted they work on classics because "in any work of genius you find an ideal logic and progression." He worked with students on their physical actions, through-lines, and rehearsing scenes based on actors' tasks. Benedetti explains, "They must avoid at all costs merely repeating the externals of what they had done the day before."

Stanislavski's Legacy

Many of Stanislavski's former students taught acting in the United States. These included Richard Boleslavsky, Maria Ouspenskaya, and Michael Chekhov. Others, like Stella Adler and Joshua Logan, built careers after short studies with him. Boleslavsky and Ouspenskaya founded the important American Laboratory Theatre (1923–1933) in New York. It was based on the First Studio. Boleslavsky's book Acting: The First Six Lessons (1933) helped spread Stanislavski's ideas in the West. In the Soviet Union, another student, Maria Knebel, continued to develop his "active analysis" rehearsal process, even though it was officially forbidden.

In the United States, one of Boleslavsky's students, Lee Strasberg, helped create the Group Theatre (1931–1940) in New York. With Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner, Strasberg developed Stanislavski's early techniques into "Method acting" (or "the Method"). He taught this at the Actors Studio. Boleslavsky thought Strasberg focused too much on Stanislavski's "emotion memory" technique and not enough on dramatic action.

For five weeks in 1934, Stanislavski worked with Adler in Paris. Adler had problems with her performances. She was surprised that Stanislavski rejected "emotion memory" except as a last resort. He suggested an indirect way to express emotion through physical action. Stanislavski confirmed this focus in discussions with Harold Clurman in 1935. This news had a big impact in the US. Strasberg angrily refused to change his approach. Adler's most famous student was actor Marlon Brando. Many American and British actors inspired by Brando also followed Stanislavski's teachings. These include James Dean, Julie Harris, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel, Dustin Hoffman, Ellen Burstyn, Daniel Day-Lewis and Marilyn Monroe.

Meisner, an actor at the Group Theatre, taught method acting at New York's Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre. He focused on what Stanislavski called "communication" and "adaptation." He named his approach the "Meisner technique." Actors trained in the Meisner technique include Robert Duvall, Tom Cruise, Diane Keaton and Sydney Pollack.

Strasberg, Adler, and Meisner are known for setting the standard of method acting's success. But each emphasized different parts: Strasberg developed the psychological aspects, Adler the social ones, and Meisner the behavioral ones. While each group tried to be different, they all shared basic ideas.

The relationships between these groups were often hostile. Each claimed to be Stanislavski's only true followers. Stanislavski's Method of Physical Action was central to Sonia Moore's efforts to correct the general idea of Stanislavski's system in America.

Experts like Carnicke have analyzed how Stanislavski's system split into psychological and physical parts in both the US and the USSR. She argues for a combination of both. She suggests that some accounts wrongly said Stanislavski completely abandoned emotion memory for a more scientific, physical approach. These accounts, which focused on physical aspects, changed the system to fit Soviet ideas. Similarly, some American accounts reinterpreted Stanislavski's work through Freudian psychoanalysis. Strasberg, for example, called the "Method of Physical Action" a step backward. But just as action was key in Stanislavski's First Studio, emotion memory was still part of his system at the end of his life. He told his directing students:

- "One must give actors various paths."

- "One of these is the path of action."

- "There is also another path: you can move from feeling to action, by first bringing up the feeling."

"Action," "if," "given circumstances," "emotion memory," "imagination," and "communication" are all chapters in Stanislavski's book An Actor's Work (1938). They were all parts of his complete system, which is hard to simplify.

Stanislavski's work didn't have much impact on British theatre before the 1960s. Joan Littlewood and Ewan MacColl were the first to introduce his techniques there. In their Theatre Workshop, Littlewood used improvisation to explore character. She insisted her actors define their character's behavior through a series of tasks. The actor Michael Redgrave also supported Stanislavski's approach in Britain. The first drama school in the country to teach acting based on Stanislavski's system was Drama Centre London. It is still taught there today.

Many other theatre practitioners have been influenced by Stanislavski's ideas. Jerzy Grotowski saw Stanislavski as the main influence on his own theatre work.

See also

- List of acting techniques

- Russian symbolism

- Russian avant-garde

- Twentieth-century theatre

- Ivana Chubbuck

- Ion Cojar

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |