Stó꞉lō facts for kids

Stó꞉lō woman with cedar baskets

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 8,876 (2017) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (British Columbia) | |

| Languages | |

| English, Upriver Halkomelem | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Animism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Coast Salish |

The Stó꞉lō (pronounced "STAW-loh") are a group of First Nations people. They live in the Fraser Valley and lower Fraser Canyon of British Columbia, Canada. They are part of the larger Coast Salish group. The word Stó꞉lō means "river" in their language, Halqemeylem. So, the Stó꞉lō are known as "the river people." People started calling them "the Stó꞉lō" in the 1880s. Before that, they were known by their smaller tribal names, like Matsqui or Sumas.

Contents

Who are the Stó꞉lō People?

The Stó꞉lō have lived in the Fraser Valley for a very long time. Evidence shows people were here between 4,000 and 10,000 years ago. The Stó꞉lō call their traditional land S'ólh Téméxw. The first people in this area were hunter-gatherers. This means they moved around to find food, hunting animals and gathering plants.

Archaeologists have found old settlements. One is in the lower Fraser Canyon, called "the Milliken site." Another is a seasonal camp near the Fraser River's mouth, called "the Glenrose Cannery site." At this camp, people hunted land and sea animals like deer, elk, and seals. They also fished for salmon, eulachon, and sturgeon. Gathering shellfish was also important. Their lives depended on successfully getting food from the land and rivers.

Stó꞉lō elders, who are respected older people, say "we have always been here." They believe their ancestors either came from the sky (Tel Swayel) or from the earth (Tel Temexw). They also tell stories of ancestral animals like the beaver and mountain goat changing into people. Special beings called Xexá:ls (transformers) made the world and its people "right." They created the landscape we see today. The Stó꞉lō feel a deep connection to the land and the Creator through these stories.

A Look at Stó꞉lō History

Ancient Times

People have lived in S'ólh Téméxw for 5,000 to 10,000 years. The Milliken and Glenrose Cannery sites are important examples. Other old sites have been found near Stave Lake and Coquitlam Lake.

Life in the Middle Period

Many more sites exist from about 5,500 to 3,000 years ago. Tools from this time are similar to older ones. A big change was the start of permanent houses. This shows people began to settle down instead of always moving. This shift happened between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago. During this time, people made decorative stone items. Their culture became more complex. The Salish Wool Dog, a special dog breed, also appeared then.

One of Canada's oldest archaeological sites is Xá:ytem, near present-day Mission. A large "transformer stone" named Xá:ytem is at the center of the site. Excavations show two main periods of settlement, one 3,000 years ago and another 5,000-9,000 years ago. Both show evidence of timber-frame houses and advanced social life. The site was later covered by floods.

Near Chehalis, there are structures called the Scowlitz Mounds. These appear to be burial mounds and are being studied. They are unique, so the people who built them might not be direct ancestors of the Stó꞉lō.

Later Ancient Times

This period goes from 3,000 years ago until Europeans arrived. New stone tools like slate knives and chisels show a more specialized society. Houses changed, suggesting families were growing larger. Warfare also became more common.

Meeting Europeans

Spanish and English explorers sailed near the coast in the late 1700s. But they did not reach the Fraser River or Stó꞉lō land directly. The first contact was indirect, through diseases spreading from other Indigenous peoples.

The Impact of Smallpox

The smallpox virus likely reached the Stó꞉lō in late 1782. It might have come from Mexico or, more likely, through trade with Europeans on the coast. It is thought that smallpox killed about 61% of the Stó꞉lō population in just six weeks. Traditional ways of caring for the sick, like gathering around them, may have spread the virus faster. Cleansing sweats and cold baths might have also harmed infected people.

Survivors often had blindness or other disabilities. This made hunting and daily life hard, leading to hunger. Stó꞉lō culture relies on oral traditions, so much important knowledge was lost. It shows the strength of the Stó꞉lō that their culture is still strong today.

By the late 1800s, the Stó꞉lō learned about vaccinations. This helped protect them from smallpox. The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic had less impact on them because many were vaccinated. However, other diseases like measles, mumps, and influenza also caused many deaths.

Early European Settlers

After the smallpox epidemic, the Stó꞉lō met Europeans face-to-face. Simon Fraser explored the Fraser River in 1808. The Hudson's Bay Company built trading posts at Fort Langley (1827) and Fort Yale (1848). Trading with the British changed how the Stó꞉lō lived and interacted with their land.

The Hudson's Bay Company first wanted to trade for furs. But salmon quickly became the main item. Between 1830 and 1849, Fort Langley's salmon purchases grew a lot. The Kwantlen Stó꞉lō moved their main village closer to the fort. This helped them keep their trading position and get protection from rival tribes. The fort helped stop slave raids by northern tribes, but these raids continued for some decades.

Land Changes and Treaties

After Simon Fraser's arrival in 1808, the gold rush began in 1858. Over 30,000 miners came, causing problems for Stó꞉lō communities. Miners moved onto Stó꞉lō land and damaged resources. This led to many arguments over land ownership. Governor James Douglas tried to separate the Stó꞉lō and the miners. This was the start of long land disputes between the Stó꞉lō and settlers.

By 1860, many miners left. More permanent settlers arrived and started farms. No treaties had been signed with the Stó꞉lō. This meant the land settlement did not follow the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This proclamation said that all land from Aboriginal peoples had to be acquired legally through treaties.

No treaties were ever made in British Columbia. Governor Douglas wanted to create them, but the gold rush made it hard. His goal was for the Stó꞉lō to adopt European farming. He hoped they would lease parts of their reserves to non-Aboriginal farmers. While waiting for treaties, he tried to create large Indian reserves. These reserves would be at least 40 hectares (about 100 acres) per family.

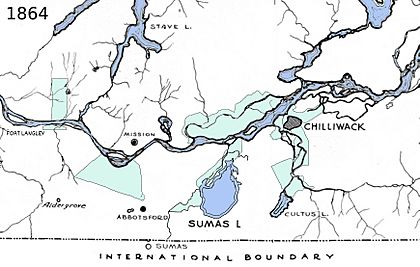

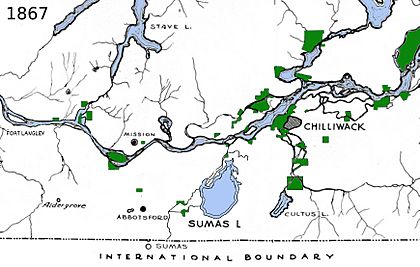

Douglas also promised the Stó꞉lō fair payment for land outside the reserves. The Stó꞉lō helped mark the reserve boundaries. They knew which lands were important, like berry patches and burial grounds. In 1864, Sergeant William McColl was told to create the reserves. He outlined 15,760 hectares (about 39,000 acres) in areas like Abbotsford and Mission. This was a lot of land, but still small compared to what settlers received.

After Douglas retired and McColl died, Joseph Trutch took charge of the reserves. He believed the Stó꞉lō did not need most of the land Douglas promised. Trutch thought land not used for farming was not needed. In 1867, he reduced the reserves by 91%. He sided with settlers who were building homes and farms. Trutch also took away many rights Douglas had given the Stó꞉lō. They could no longer participate in government or buy land outside reserves.

For many years, governments paid little attention to these problems. In 1990, British Columbia recognized that Aboriginal land rights needed to be settled by treaty. They created the BC Treaty Commission to help with these issues.

St. Mary's Residential School

St. Mary's Indian Residential School was a residential school in Mission. It was first run by the Roman Catholic Church and then by the Canadian government. About 2,000 children attended, mostly Stó꞉lō. It opened in 1863 for boys. A girls' section opened in 1868. The school moved in 1882 for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Boys and girls lived separately. They had shared dining halls, laundries, and classrooms. The school focused on Catholic teachings and academics. Later, they taught farming and industrial skills like woodworking and sewing.

Parents could visit and sometimes camped near the school. Students could visit Mission until 1948. When students arrived, they got lockers, beds, and dormitory space. They were checked for lice and given two sets of marked clothes.

Stories about abuse at the school vary. Some accounts say there was no physical punishment in the 1800s. But later, strapping became common, and conditions were very bad for some students.

In 1952, 16 students graduated with high school diplomas. In 1961, students moved to a new government-run school. The old Catholic school closed. By 1985, all buildings of the former schools were gone. The land is now part of Fraser River Heritage Park. A new bell tower, built in 2000, holds the original 1875 bell from Mission. In 2005, the park land was returned to the Stó꞉lō. It is now an Indian reserve called pekw’xe: yles. Twenty-one different First Nations governments use this land.

Stó꞉lō Culture

Language: Halq'eméylem

The traditional language of the Stó꞉lō people is Halq'eméylem. This is the "Upriver dialect" of Halkomelem. It is spoken in areas like Harrison Lake and the Fraser Valley. Halq'eméylem is part of the Coast Salish language family.

While there are 278 fluent speakers of Halkomelem dialects, fewer than five people speak Halq'eméylem fluently. These speakers are very old. Because of this, the language is in danger of disappearing.

In residential schools like St. Mary's, students were not allowed to speak their language. If they spoke Halq'eméylem, they were often punished. This caused many students to lose their language. Today, English is still more common than Halq'eméylem. As fluent speakers pass away, fewer children learn the language at home.

The Stó꞉lō people see their language as a key part of their culture. They are working hard to bring Halq'eméylem back. The Stó꞉lō Shxweli Halqʼeméylem Language Program started in 1994. Its goal was to teach the language to community members. They also wanted to create learning materials in Halq'eméylem.

This program now works with universities in British Columbia. Students can take Halq'eméylem courses at the University of the Fraser Valley, Simon Fraser University, and the University of British Columbia.

The program also uses technology to save the language. They have an online language archive on the First Voices app and website. It includes 1,745 words and 667 phrases in Halq'eméylem.

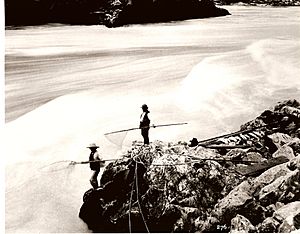

The Importance of Salmon

Coast Salish villages were built near rivers and waterways. This gave them access to water and good salmon fishing spots. Salmon was so important that they had special ceremonies for it. The Stó꞉lō fished in the Fraser River and its smaller rivers, like the Chilliwack and Harrison River. The life cycle of the salmon was a big part of community life. The First Salmon Ceremony, held when the first fish was caught each year, showed how important salmon was.

During the First Salmon Ceremony, the first salmon caught was shared with the community or family. After eating the fish, the bones were returned to the river. This showed respect to the "salmon people." If the ceremony was not done, people believed the fisher would have bad luck. They also thought the salmon run might not be strong.

Salmon was the favorite food of the Stó꞉lō. They believed it gave them energy, while other meats made them feel tired. To have salmon all year, they preserved it. In summer, salmon was wind-dried with salt in the Fraser Canyon. In fall, it was smoked. Traditionally, smoking took a week or two. Today, with fridges, it only takes a few days. Dried salmon was boiled or steamed before eating.

Salmon was also important for trading. When the Hudson's Bay Company set up trading posts, they first wanted beaver furs. But they soon saw the large salmon catches. In August 1829, the Stó꞉lō traded 7,000 salmon to Fort Langley.

Since European settlement, salmon numbers have decreased. This is due to things like the building of the CPR railway, farming, and logging. A newer problem is the growing farmed salmon industry. Farmed salmon can spread lice and diseases to wild salmon. This further harms the already shrinking numbers.

How Stó꞉lō Society Was Organized

Stó꞉lō society had different groups of people. There were the sí꞉yá꞉m (upper classes), ordinary people, and slaves. Slaves were usually captives from enemy tribes. A person's family status was important in Stó꞉lō society. Slaves were treated fairly well, but they could not eat with others at the Longhouse fire. They mainly did daily tasks like gathering food or firewood. The use of slaves ended in the 1800s. There was even a settlement for former slaves called Freedom Village.

The Síyá꞉m (leader) were the most important members of each family. Expert hunters were called Tewit and led during hunting season. Leaders with influence over whole villages were sometimes called Yewal Síyá꞉m (high leaders).

Homes and Shelters

The main type of home for the Stó꞉lō was the longhouse. Some modern longhouses have sloped roofs. But most Stó꞉lō longhouses had a single flat, slanted roof, like the Xá:ytem Longhouse. Whole extended families lived in one longhouse. The building could be made longer as the family grew. Pit houses (or Quiggly hole houses) were also used in earlier times.

Travel and Transportation

The Stó꞉lō built canoes for rivers and lakes. Larger ocean-going canoes were usually gotten through trade with coastal Indigenous people. In the late 1800s, people started using horse and buggy, then trains and cars, instead of water travel.

Growing Up: Adolescence

Traditionally, Stó꞉lō girls had special ceremonies when they reached puberty. A girl would go to a pit lined with cedar branches. She would stay there during the day, only leaving to eat and sleep. Older women would bring her fir branches and tell her to pick off the needles. This was the only work she did. Other women would feed and wash her until her first period ended. This custom was widely practiced until youth were sent to residential schools.

Stó꞉lō Governments Today

The Stó꞉lō have two elected tribal councils: the Sto꞉lo Nation Chiefs Council and the Stó꞉lō Tribal Council. Some bands belong to both councils.

Six bands do not belong to either council. The Chehalis Indian Band is one example. While they are similar in culture and language, they have chosen to be separate from the main Stó꞉lō collective government. Other First Nations in the region, like the Musqueam Indian Band and Yale First Nation, also govern themselves separately.

Bands in the Stó꞉lō Nation Chiefs Council

- Aitchelitz First Nation

- Leq'a:mel First Nation

- Matsqui First Nation

- Popkum First Nation

- Skway First Nation

- Skawahlook First Nation

- Skowkale First Nation

- Squiala First Nation

- Sumas First Nation

- Tzeachten First Nation

- Yakweakwioose First Nation

Bands in the Stó꞉lō Tribal Council

- Chawathil First Nation

- Cheam Indian Band

- Kwaw-kwaw-Apilt First Nation

- Scowlitz First Nation

- Seabird Island First Nation (a group of people from many different Coastal First Nations)

- Shxwʼowʼhamel First Nation

- Soowahlie First Nation

Stó꞉lō Bands Not in a Tribal Council

- Kwantlen First Nation

- Skwah First Nation

- New Westminster Indian Band (a group of people from many different Coastal First Nations)

- Kwikwetlem First Nation

- Union Bar First Nation

- Peters Band

- Katzie First Nation

- Chehalis First Nation

Treaty Negotiations in British Columbia

The Stó꞉lō Declaration was signed in 1977 by twenty-four First Nations. In August 1995, twenty-one of these nations joined the British Columbia Treaty Process as the Sto꞉lo Nation Chiefs Council. Four First Nations later left the process. This left seventeen nations to reach Stage Four of the six-stage process.

In 2005, the nineteen Stó꞉lō First Nations reorganized into two tribal councils. Eleven nations chose to stay in the Stó꞉lō Nation. These include Aitchelitz, Leq'a:mel, Matsqui, Popkum, Shxwhá:y Village, Skawahlook, Skowkale, Squiala, Sumas, Tzeachten, and Yakweakwioose.

Eight other nations formed the Stó꞉lō Tribal Council. These eight members are Chawathil, Cheam, Kwantlen First Nation, Kwaw-kwaw-Apilt, Scowlitz, Seabird Island, Shxw'ow'hamel First Nation, and Soowahlie. These eight nations are not part of the treaty process.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |