Stony corals facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stony corals |

|

|---|---|

|

|

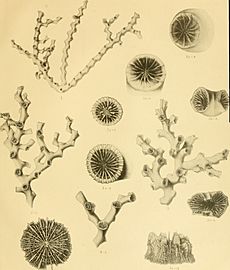

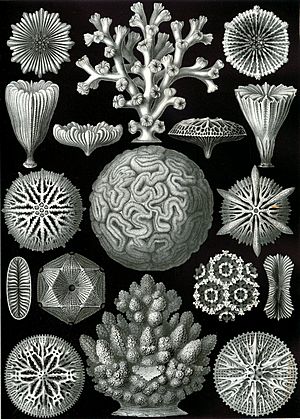

| Scleractinian corals, illustration by Ernst Haeckel, 1904 |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Anthozoa |

| Subclass: | Hexacorallia |

| Order: | Scleractinia Bourne, 1900 |

| Families | |

|

About 35, see text. |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Scleractinia, also known as stony corals or hard corals, are fascinating sea animals that build their own hard skeletons. These animals belong to the group (phylum) Cnidaria, which also includes jellyfish and sea anemones.

Each tiny animal is called a polyp. It has a soft, tube-like body with a mouth at the top, surrounded by a ring of tentacles. While some stony corals live alone, most live together in large groups called colonies.

A colony starts when a single polyp attaches to the seafloor. It begins to release calcium carbonate (the same material that makes up chalk and seashells) to build a protective cup around its soft body. This first polyp then makes copies of itself by budding, and these new polyps stay connected. Over time, they form a large colony with a shared skeleton that can grow to be several meters wide.

The shape of a coral colony depends on the species and where it lives. Factors like water depth and how much the water moves can change its appearance. Many corals in shallow water have tiny algae called zooxanthellae living inside their tissues. These algae give corals their beautiful colors and are very important for their health.

Stony corals are found in oceans all over the world. They are the main builders of coral reefs, which are incredibly important ecosystems for many other sea creatures.

Contents

What Do Stony Corals Look Like?

Stony corals can be found as single individuals or as large colonies made up of thousands of polyps.

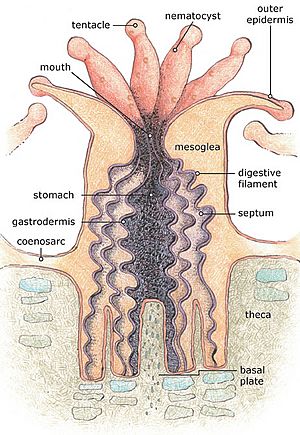

The Polyp's Body

Like their relatives the sea anemones, stony corals are made of tiny animals called polyps. The polyp has a simple, cylinder-shaped body. At the top is a mouth surrounded by tentacles, which are used to catch food. The base of the polyp is what creates the hard skeleton.

The polyp's body has a stomach-like space inside. When it feels threatened, the polyp can pull itself back into its stony cup for safety.

In a colony, all the polyps are connected by a thin layer of living tissue called the coenosarc. This tissue covers the skeleton and allows the polyps to share food and water with each other, working together as one big organism.

The Hard Skeleton

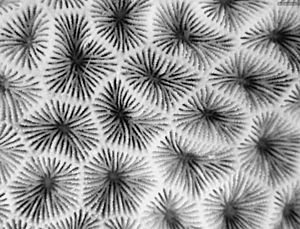

The skeleton that a single polyp builds for itself is called a corallite. It's a stony cup made of aragonite, a form of calcium carbonate. Inside the cup, thin, wall-like plates called septa grow upwards from the base. These septa provide extra support and structure for the polyp.

The skeleton of a stony coral is strong but also lightweight and porous, meaning it has tiny holes in it. This is different from some ancient types of corals that had solid, heavier skeletons.

How Do Corals Grow?

Colonial corals grow when their polyps make copies of themselves through a process called budding.

- Intratentacular budding happens when a new polyp grows from inside the parent polyp's ring of tentacles. This can create the winding, maze-like patterns seen in brain corals.

- Extratentacular budding happens when a new polyp grows from the base of the parent polyp, outside the tentacles. This often results in branching corals, like the staghorn coral (Acropora).

The speed of coral growth varies. Some branching corals can grow about 10 cm (4 in) a year, which is about as fast as human hair grows. Other corals that form massive boulder or plate shapes grow much more slowly, only adding 0.3 to 2 cm (0.1 to 0.8 in) per year. By looking at growth bands in a coral's skeleton, similar to tree rings, scientists can figure out how old it is.

Solitary corals, which live alone, do not bud. They just get bigger over time by adding more material to their skeleton.

Where Do Stony Corals Live?

Stony corals can be found in every ocean on Earth. They are generally divided into two groups based on where they live and what they do.

- Reef-building corals (hermatypic corals) are the corals that create the structure of coral reefs. They usually live in shallow, clear, warm tropical waters where sunlight can reach them.

- Non-reef-building corals (ahermatypic corals) do not form reefs. They can be found in all parts of the ocean, from tropical seas to cold, dark polar waters. Some live at incredible depths, as far down as 6,000 m (20,000 ft).

How Corals Live and Eat

Stony corals have different ways of getting the food they need to survive.

The Role of Algae

Most reef-building corals have a special partnership, called symbiosis, with tiny algae called zooxanthellae. Millions of these algae live inside the coral's tissues.

Through photosynthesis, the algae use sunlight to make food. They share this food with the coral, giving it the energy it needs to grow and build its skeleton. In return, the coral provides the algae with a safe place to live. This teamwork allows reef-building corals to grow much faster than corals without algae.

Catching Food

In addition to the food they get from algae, most stony corals are also hunters. At night, their polyps extend their tentacles to catch tiny floating animals called zooplankton. Some corals with larger polyps can even catch small fish.

Many corals also produce a sticky mucus to trap tiny bits of food floating in the water. They then use tiny hairs called cilia to move the mucus and the food into their mouths.

Corals that live in deep, dark water do not have zooxanthellae. They get all their energy by catching plankton and other food particles from the water.

Life Cycle

Stony corals can reproduce in two main ways: asexually (without a partner) and sexually.

Asexual Reproduction

The most common way corals reproduce asexually is through fragmentation. If a piece of a branching coral breaks off during a storm, it can land on the seafloor, attach itself, and start growing into a whole new colony.

Some corals have a clever survival trick called "polyp bail-out." If the main colony is dying, individual polyps can detach themselves, float away, and settle somewhere new to start a new colony.

Sexual Reproduction

Most stony coral species reproduce sexually by releasing eggs and sperm into the water. This is called spawning. These events are often synchronized with the phases of the moon, with many colonies on a reef releasing their eggs and sperm all at the same time.

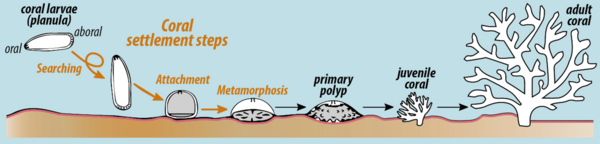

When an egg is fertilized, it develops into a tiny, swimming larva called a planula. The planula drifts in the ocean currents until it finds a suitable hard surface to settle on. Once it attaches, it transforms (metamorphosis) into a polyp and begins to build its skeleton, starting a new colony.

A Brief History of Stony Corals

Scientists are still learning about the ancient history of stony corals. The oldest fossils we have found are from the Middle Triassic period, about 240 million years ago. These early corals were small and lived alone, unlike the massive reef-builders we see today.

It took about 25 million years for stony corals to become major reef-builders. Their success may have been linked to when they first formed a partnership with symbiotic algae.

The ancestors of stony corals are a bit of a mystery. They may have evolved from an anemone-like animal that did not have a skeleton. They are very different from the older rugose corals of the Paleozoic era, which had skeletons made of a different material (calcite) and a different internal structure.

Like the dinosaurs, many coral species were wiped out during the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. However, about 18 groups (genera) survived and evolved into the thousands of species we have today.

How Scientists Group Corals

Figuring out how to group, or classify, stony corals is a big challenge for scientists. In the past, scientists could only study corals found in shallow water. They didn't realize that the same coral species can look very different depending on where it grows.

Originally, corals were classified based only on the shape and structure of their skeletons. However, with modern technology, scientists can now study coral DNA. This genetic information has changed our understanding of how different coral species are related.

Molecular studies have shown that some corals that look very different are actually closely related, while some that look similar are not. Today, scientists use a combination of both skeleton shape and DNA to create a more accurate classification of stony corals.

Conservation

All stony corals (except for fossils) are protected under an international agreement called CITES. This means that trading them internationally is regulated to help protect them from being over-harvested.

Families

The World Register of Marine Species lists the following families in the order Scleractinia. Some species have not yet been placed in a family.

- Acroporidae

- Agariciidae

- †Agathiphylliidae

- Anthemiphylliidae

- Astrocoeniidae

- Caryophylliidae

- Coscinaraeidae

- Deltocyathidae

- Dendrophylliidae

- Diploastreidae

- Euphylliidae

- Flabellidae

- Fungiacyathidae

- Fungiidae

- Gardineriidae

- Guyniidae

- Lobophylliidae

- Meandrinidae

- Merulinidae

- Micrabaciidae

- Montastraeidae

- Mussidae

- Oculinidae

- †Oulastreidae

- Plesiastreidae

- Pocilloporidae

- Poritidae

- Psammocoridae

- Rhizangiidae

- Schizocyathidae

- Siderastreidae

- Stenocyathidae

- †Stylinidae

- Turbinoliidae

- Mussidae accepted as Faviidae

See also

In Spanish: Escleractinios para niños

In Spanish: Escleractinios para niños

- Environmental issues with coral reefs

- Corals of the World, a website by J. E. N. Veron specialized in Scleractinia.

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |