Ming treasure voyages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ming treasure voyages |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

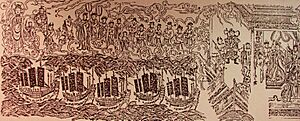

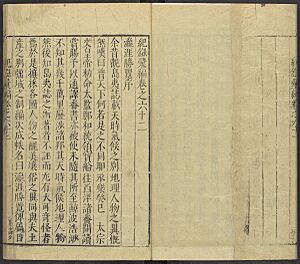

Several of Zheng He's ships as depicted in the Wubei Zhi, dated to the early 17th century

|

|||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭和下西洋 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郑和下西洋 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | [Voyages of] Zheng He down the Western Ocean | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The Ming treasure voyages were amazing sea journeys made by China's huge 'treasure fleet' between 1405 and 1433. The Yongle Emperor decided to build this fleet in 1403. These grand projects led to seven long ocean trips. The ships sailed to islands and coastal lands in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. Admiral Zheng He was chosen to lead these powerful fleets.

Six of these voyages happened during the Yongle Emperor's rule (1402–1424). The seventh trip was during the Xuande Emperor's time (1425–1435). The first three voyages reached Calicut on India's Malabar Coast. The fourth voyage went even further, to Hormuz in the Persian Gulf. In the last three journeys, the fleet traveled to the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa.

China's expedition fleet was very strong and carried many treasures. These trips showed the world China's power and wealth. They brought back many foreign leaders who wanted to be friends with China. During these voyages, the fleet also fought and won battles. They defeated a pirate fleet near Palembang. They captured the Kotte kingdom in Ceylon and beat a ruler in northern Sumatra.

These sea trips brought many countries into China's tributary system. This meant these countries became part of China's influence. China also helped organize a huge sea trade network. This connected many countries economically and politically.

The Ming treasure voyages were managed by eunuchs. Their power depended on the emperor's favor. Other government officials often disagreed with the eunuchs and these voyages. As the voyages ended, these civil officials gained more power. The eunuchs lost influence after the Yongle Emperor died. This made it harder to continue such big projects. Also, local traders didn't like the government controlling all the trade.

During these voyages, Ming China became the top naval power in the region. They showed their strength far to the south and west. Historians still discuss many things about these voyages. For example, why they happened, how big the ships were, and exactly where they went.

Building the Great Fleet

How the Fleet Started

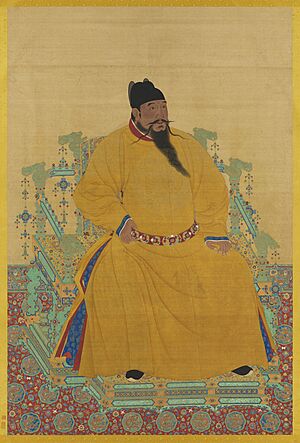

On July 17, 1402, Zhu Di became the Yongle Emperor in Ming China. He inherited a strong navy from his father. He made it even bigger to explore and expand China's reach overseas. Records show that between 1403 and 1419, at least 2,868 ships were built.

In 1403, the emperor ordered provinces like Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang to start building ships. Cities like Nanjing and Suzhou also helped. Under the Yongle Emperor, Ming China expanded its power. The treasure voyages were a big part of this.

The fleet was first called the "foreign expeditionary armada." It included many trading ships, warships, and support vessels. The Longjiang shipyard near Nanjing built many of these ships. This included all the huge treasure ships. Trees from the Min River and Yangtze River were used to build them. Some existing ships were also changed to join the fleet. We know for sure that 249 ships were converted in 1407.

High-ranking officers, like Admiral Zheng He, were eunuchs. Zheng He was a top official before leading the expeditions. The emperor trusted Zheng He greatly. He even gave him blank scrolls with his own seal. This allowed Zheng He to issue imperial orders while at sea. Other main officers were also eunuchs. Most of the crew came from the Ming military, especially from Fujian.

Where the Journeys Began

The Chinese treasure fleet started its voyages from the Longjiang shipyard. They sailed down the Yangtze River to Liujiagang. Here, Zheng He organized the fleet and prayed to Tianfei, the goddess of sailors.

For the next four to eight weeks, the fleet slowly moved to Taiping anchorage in Changle. They waited there for the right winds. These were the northeast winter monsoon winds, usually in December and January. These winds helped the fleet sail through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. They reached the open sea through the Wuhumen ('five tiger passage') in Fujian. The port of Qui Nhon in Champa was always their first stop in a foreign land.

The voyages took the fleet to the Western Ocean. This was the name for today's South China Sea and Indian Ocean during the Ming dynasty. Old maps show the dividing line between the Eastern and Western Oceans was at Brunei.

The first three voyages (1405–1411) followed a similar path. From Fujian, they went to Champa, then across the South China Sea to Java and Sumatra. They sailed up the Strait of Malacca to northern Sumatra to gather the fleet. Then, they crossed the Indian Ocean to Ceylon, and along the Malabar Coast to Calicut. They didn't go further than Calicut on these trips.

For the fourth voyage, the route was extended to Hormuz. In the fifth, sixth, and seventh voyages, the fleet traveled even further. They reached places in the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa. For the sixth voyage, the fleet went to Calicut. From there, smaller groups of ships went to the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa. For the seventh voyage, the fleet went to Hormuz. Again, smaller groups traveled to other places in Arabia and East Africa.

The Journeys Themselves

First Voyage (1405–1407)

In March or April of 1405, Admiral Zheng He and others were ordered to lead 27,000 troops to the Western Ocean. The official order was given on July 11, 1405.

The Yongle Emperor held a big dinner for the crew before their first journey. Officers and crew received gifts based on their rank. They prayed to Tianfei, the goddess of sailors, for a safe and successful trip. In the autumn of 1405, the fleet gathered in Nanjing and was ready to leave. Zheng He and others carried imperial letters and gifts for foreign kings. The fleet stopped at Liujiagang to organize. They prayed to Tianfei again at Changle while waiting for the monsoon winds. Then, they sailed out through the Wuhumen.

The fleet visited Champa, Java, Malacca, Aru, Semudera, Lambri, Ceylon, Quilon, and Calicut. From Lambri, they sailed directly across the Indian Ocean to Ceylon. They arrived at Ceylon's western coast. They left this area because the local ruler, Alakeshvara, was unfriendly.

On their way back in 1407, Zheng He's fleet fought a pirate leader named Chen Zuyi near Palembang. Chen Zuyi had taken control of Palembang and the sea route. The Chinese fleet defeated Chen's pirates. Chen and his helpers were executed when the fleet returned to Nanjing on October 2, 1407. China then appointed a friendly leader in Palembang. This helped secure access to its important port.

After returning, foreign envoys from Calicut, Quilon, Semudera, and other places visited the Ming court. They paid their respects and offered local products as gifts. The Yongle Emperor ordered gifts to be prepared for their kings.

Second Voyage (1407–1409)

The order for the second voyage was given in October 1407. Zheng He, Wang Jinghong, and Hou Xian were in charge.

The fleet left Nanjing in late 1407 or early 1408. They traveled from Nanjing to Liujiagang, then to Changle. From there, they sailed to Champa, Siam, Java, Malacca, Semudera, Aru, Lambri, and various cities in India like Quilon, Cochin, and Calicut. During this trip, the fleet did not stop in Ceylon. Their mission included formally recognizing Mana Vikraan as the King of Calicut. A stone tablet was placed in Calicut to celebrate the friendship between China and India.

On this voyage, China also dealt with a problem in Java. In a civil war there, the King of West Java had mistakenly killed 170 members of a Chinese group. China demanded a large amount of gold as payment. The Javanese king apologized and paid. China accepted and restored friendly relations. The Chinese continued to keep an eye on Java during future voyages.

The fleet returned to Nanjing in the summer of 1409. There's some debate among historians about whether Zheng He himself was on this second voyage. However, one account mentions him visiting Pulau Sembilan in 1409, suggesting he was indeed present.

Third Voyage (1409–1411)

The order for the third voyage was given in early 1409. Zheng He, Wang Jinghong, and Hou Xian were again the leaders.

Zheng He started this voyage in 1409. The fleet left Liujiagang in October or November 1409 and arrived at Changle the next month. They left Changle in January or February 1410, sailing through the Wuhumen. They stopped at Champa, Java, Malacca, Semudera, Ceylon, Quilon, Cochin, and Calicut. They reached Champa in just 10 days. The fleet landed at Galle, Ceylon, in 1410.

On the way back in 1411, the Chinese fleet faced King Alakeshvara of Ceylon. He was causing trouble for nearby countries and ships. The Chinese found the Sinhalese people rude and hostile. They also didn't like that the Sinhalese attacked friendly neighboring countries. Zheng He and 2,000 troops went inland into Kotte. Alakeshvara tried to trap Zheng He and attack the Chinese fleet at Colombo. But Zheng He and his troops invaded Kotte and captured its capital. The Sinhalese army, reportedly over 50,000 strong, tried to fight back but were defeated. Zheng He captured Alakeshvara, his family, and top officials.

Zheng He returned to Nanjing on July 6, 1411. He presented the captured Sinhalese to the Yongle Emperor. The emperor decided to free them and send them home. The Chinese removed Alakeshvara from power. They supported their friend Parakramabahu VI as the new king. After this, the fleet had no more problems visiting Ceylon.

Fourth Voyage (1413–1415)

On December 18, 1412, the Yongle Emperor ordered the fourth voyage. Zheng He and others were again in command.

This expedition took the Chinese treasure fleet to Muslim countries. So, it was important to find good interpreters. Ma Huan joined the voyages for the first time as an interpreter. A mosque in Xi'an records that in 1413, Zheng He found Hasan, who spoke Arabic, to join this voyage.

The fleet left Nanjing in 1413, probably in autumn. They sailed from Fujian in late 1413 or early 1414. Calicut was the furthest west they had gone before, but this time they went beyond it. Records show stops at Malacca, Java, Champa, Semudera, Cochin, Calicut, Hormuz, and the Maldives.

At Java, the fleet delivered gifts from the Yongle Emperor. In return, a Javanese envoy came to China in 1415. They brought gifts and thanked the emperor.

In 1415, on the way back, the fleet stopped in northern Sumatra. Here, Sekandar had taken the throne from Zain al-'Abidin, whom China recognized as the rightful king. Zheng He was ordered to attack Sekandar and put Zain al-'Abidin back in power. Sekandar's forces, said to be "tens of thousands," attacked the Ming forces but were defeated. The Ming forces captured Sekandar, his wife, and child. King Zain al-'Abidin later sent a mission to thank China. This conflict showed China's power and protected trade routes. Sekandar was executed in Nanjing after the fleet returned.

On August 12, 1415, the fleet returned to Nanjing. The Yongle Emperor was away fighting the Mongols. After the fleet's return, envoys from 18 countries came to the Ming court with gifts.

Fifth Voyage (1417–1419)

On November 14, 1416, the Yongle Emperor returned to Nanjing. On November 19, he held a big ceremony. He gave gifts to princes, officials, and ambassadors from 18 countries. On December 28, the ambassadors left, and the emperor ordered the fifth voyage. Its goal was to take the ambassadors home and reward their kings.

Zheng He and others were ordered to escort the ambassadors. They carried imperial letters and gifts. The King of Cochin received special treatment. He had sent gifts to China since 1411. The emperor gave him a special title and called a hill in Cochin "State Protecting Mountain."

Zheng He likely left China in the autumn of 1417. He stopped at Quanzhou to load the ships with porcelain and other goods. Old Chinese porcelain has been found in East African places the fleet visited. The fleet visited Champa, Java, Malacca, Semudera, Ceylon, Cochin, Calicut, Hormuz, Aden, Mogadishu, and Malindi. For Arabia and East Africa, the route was likely Hormuz, then Aden, Mogadishu, and Malindi. Records say Chinese ships reached Aden in January 1419.

On August 8, 1419, the fleet returned to China. The Yongle Emperor was in Beijing. He ordered rewards for the fleet's crew. The foreign ambassadors were received at the Ming court in August or September 1419. They brought amazing animals like lions, leopards, camels, ostriches, zebras, and giraffes. These exotic animals caused a sensation at the Ming court.

In late 1420, the emperor announced that the capital would move to Beijing. He arranged for all foreign envoys to travel to the new capital for a celebration in early 1421.

Sixth Voyage (1421–1422)

On March 3, 1421, the emperor ordered the sixth voyage. Its purpose was to take the envoys of sixteen countries back home. Zheng He was sent with imperial letters and gifts for their rulers.

The envoys were escorted by the fleet. The first stops were likely Malacca and three Sumatran states. The fleet then split into smaller groups at Semudera. All groups went to Ceylon. From there, they separated for different cities in southern India like Cochin or Calicut. The groups then traveled to their own destinations. These included the Maldives, Hormuz, and Arabian states like Aden. Two African states, Mogadishu and Brava, were also visited. The eunuch Zhou Man led a group to Aden.

On their way back, several groups met at Calicut. All groups then met again at Semudera. Siam was likely visited on the return journey. The fleet returned on September 3, 1422. They brought envoys from Siam, Semudera, Aden, and other countries. These envoys traveled overland or by canal to Beijing in 1423.

Some Chinese ships did not return with the main fleet. Records show a Chinese group was received in the capital of the Rasulid Sultanate in January 1423.

The Fleet Stays in Nanjing (1421–1431)

On May 14, 1421, the Yongle Emperor ordered a temporary stop to the treasure voyages. Money and attention shifted to his military campaigns against the Mongols. Between 1422 and 1431, the Chinese treasure fleet stayed in Nanjing. It served as the city's defense.

In 1424, Zheng He went on a diplomatic trip to Palembang. Meanwhile, the Yongle Emperor died on August 12, 1424. His son, Zhu Gaozhi, became the Hongxi Emperor on September 7, 1424. Zheng He returned from Palembang after the emperor's death.

The Hongxi Emperor did not like the voyages. On the day he became emperor, he stopped all future voyages. He kept the treasure fleet in Nanjing for defense. On February 24, 1425, he made Zheng He the defender of Nanjing. He ordered Zheng He to continue commanding the fleet for the city's protection. The Hongxi Emperor died on May 29, 1425. His son, Zhu Zhanji, became the Xuande Emperor. The Xuande Emperor kept his father's arrangements, so the fleet remained in Nanjing.

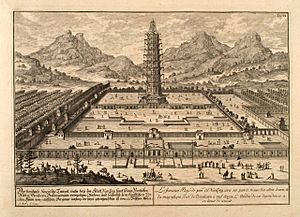

On March 25, 1428, the Xuande Emperor ordered Zheng He to oversee the rebuilding of the Great Bao'en Temple in Nanjing. The temple was finished in 1431. It's possible that money for the temple came from funds meant for the treasure voyages.

Seventh Voyage (1431–1433)

On May 25, 1430, an order was given to prepare for Zheng He and other officials to go to the Western Ocean. On June 29, 1430, the Xuande Emperor issued his orders for the seventh voyage. He wanted to bring back the friendly relations that were strong during the Yongle Emperor's time.

The fleet left Nanjing on January 19, 1431. They arrived at Liujiagang on February 3 and Changle on April 8. They left Changle in December. On January 12, 1432, they sailed through the Wuhumen. They arrived at Vijaya in Champa on January 27 and left on February 12. They reached Surabaya in Java on March 7 and left on July 13. The fleet arrived at Palembang on July 24 and left on July 27. They arrived at Malacca on August 3 and left on September 2. They reached Semudera on September 12 and left on November 2. They arrived at Beruwala in Ceylon on November 28 and left on December 2. They reached Calicut on December 10 and left on December 14. Finally, they arrived at Hormuz on January 17, 1433, and left on March 9.

Hormuz was the furthest west of the main stops on this voyage. Other records say the fleet visited at least seventeen countries. These included Bengal, the Maldives, Aden, Mecca, Mogadishu, and Brava. One account mentions a stop at the Andaman and Nicobar islands in November 1432.

Zheng He is mentioned visiting several places like Mogadishu and Brava. It's not clear if he went to all these places in person. However, the records say he delivered imperial instructions to their kings.

Hong Bao commanded a group of ships that went to Bengal. Ma Huan was with this group. They sailed directly from Semudera to Bengal. In Bengal, they visited Chittagong and the capital Gaur. Then they sailed directly to Calicut. By the time Hong's group arrived, the main fleet had already left Calicut for Hormuz. Ma Huan wrote that Hong sent seven men on a ship to Mecca. They returned a year later with goods and exotic animals like giraffes, lions, and ostriches. Ma Huan was likely one of the people who visited Mecca.

The fleet returned from Hormuz on March 9, 1433. They arrived at Calicut on March 31 and left on April 9. They reached Semudera on April 25 and left on May 1. On May 9, they arrived at Malacca. They reached the Kunlun Ocean on May 28. They arrived at Vijaya on June 13 and left on June 17. The fleet arrived at Taicang on July 7. On July 22, 1433, they arrived in the capital, Beijing. On July 27, the Xuande Emperor gave gifts to the fleet's crew.

The fleet returned with envoys from 11 countries, including Mecca. On September 14, 1433, these envoys came to the court to present gifts.

What Happened Next

The End of the Voyages

During the treasure voyages, Ming China became the strongest naval power in the early 1400s. The Yongle Emperor had extended China's influence over foreign lands. However, in 1433, the voyages stopped. Ming China then turned away from the seas. Admiral Zheng He himself died in 1433 or 1435.

Trade continued to be strong long after the voyages ended. Chinese ships still controlled trade in East Asia. They also kept trading with India and East Africa. But the imperial tributary system and government control over foreign trade slowly weakened. Private trade took its place. The voyages were meant to connect the Ming court directly with foreign states. This helped avoid private traders and local officials who tried to stop overseas trade. When the voyages ended, foreign trade shifted to local authorities. This further weakened the central government's power.

The military and nobles were powerful during the Hongwu and Yongle reigns. But political power slowly moved to the civil government. Because of this, the eunuch group couldn't get enough support for projects that civil officials opposed. These officials were always careful about any attempts by eunuchs to restart the voyages. When China's treasure fleet left, it created a power gap in the Indian Ocean.

Why Did They Stop?

It's not fully known why the Ming treasure voyages completely ended in 1433. Some historians suggest the high costs were a reason. However, others argue that the voyages were profitable and didn't put too much strain on China's treasury. They say the voyages actually made money for the state.

Civil officials disliked eunuchs because they interfered in government. But much of this strong dislike happened after the voyages ended. At that time, eunuchs used their power to get rich and punish critics. So, the conflict between these groups might not fully explain why the voyages stopped. Zheng He himself was respected by many high officials.

Some believe that traditional Confucian ideas caused the voyages to end. They say Confucian beliefs led to a general dislike for overseas trips. However, other historians argue that the criticism was more about the eunuchs gaining too much power. They felt eunuchs shouldn't have duties outside the court. Confucian officials did play a role in stopping the voyages. But they were probably more interested in protecting their own power. The voyages were controlled by their rivals, the eunuchs.

Some historians say that traders and officials, wanting to protect their own money, slowly broke down the system that supported state-controlled sea trade. They also made it harder for private trade with strict rules. Rich and powerful people used their connections in Beijing to stop efforts to bring trade back under government control. They wanted to protect their own business interests.

Another idea is that the voyages stopped because of money disagreements between emperors and civil officials. The Yongle Emperor used money from the national treasuries for his building projects and wars, including the voyages. He controlled the trade income to fund his plans. This increased his power over money matters. Civil officials were asked to raise money for the voyages, but they had no say in the trade income. The emperor had given eunuchs control over trade and its profits. So, the voyages became a target for officials' criticism. Even though the voyages were a small part of the government's budget, they showed a new way of sharing money power. This new way left officials out of the budget process.

In 1435, when the Xuande Emperor died, civil officials gained more power. The new emperor, the Zhengtong Emperor, was only eight years old. Officials used this chance to permanently stop the voyages. They did this in several ways:

- They reduced the power of the imperial navy. Plans for more voyages were canceled. Offices related to sea travel were closed. Seagoing ships were destroyed or changed so they couldn't travel far. Sailors were moved to river transport work.

- They stopped the court from making goods for export. They ended the large-scale production of export products. All eunuchs and officials sent to oversee manufacturing were called back.

- They made it harder for foreigners to visit China. From 1435, officials urged foreign groups to leave China. The court sent them to Malacca and asked them to change ships there. This was different from before, when China would send them all the way home. Transport services for visiting groups stopped. The size of foreign groups was limited, and how often they could visit was reduced. The office that handled overseas visitors was made smaller.

- They limited the eunuchs' power over money. They took over the imperial treasuries from the eunuchs. They also asked the eunuchs to hand over records of overseas products to the government.

Impact of the Voyages

Goals and Results

The Ming treasure voyages had diplomatic, military, and commercial goals. They aimed to control sea trade. They also wanted to bring foreign countries into China's tributary system. The diplomatic part included announcing the Yongle Emperor's rule. It also meant showing China's power over foreign countries. And it provided safe passage for foreign envoys bringing gifts. The emperor may have wanted to show his rule was rightful. He had taken the throne by force.

The Chinese did not want to control land. Their main goal was to control trade and shipping routes. One historian says the voyages tried to balance China's need for sea trade with the government's rules against private trade. They wanted to show China's power over sea commerce. China's economy did not need to take resources from other countries. Trading centers along the sea routes stayed open to other foreigners. They were not taken over. This helped promote international trade.

The voyages changed how the sea trade network worked. They created new connections and routes. This changed international relationships. No other power had controlled all parts of the Indian Ocean before these voyages. Historians say China built friendly tributary relations. Foreign countries worked with China because it benefited them. This included setting up official trading posts overseas. These posts involved local officials and merchants. Large-scale trade happened here between the Chinese and local people. This helped these places become important trade hubs. Ming China promoted new ports to control the sea network. For example, Chinese involvement helped ports like Malacca, Cochin, and Malindi grow. The sea network and its centers, promoted during the voyages, continued to be important for later sea travel and trade. Through the voyages, Ming China got involved in foreign countries' affairs. They supported friendly rulers. They captured or executed rivals. They also threatened unfriendly rulers to make them cooperate. The arrival of the Chinese fleet made countries compete. They all wanted to be friends with the Ming.

The tributary relations during the voyages led to more connections between regions. This was an early step towards globalization in Asia and Africa. The voyages brought the Western Ocean region closer together. It increased the movement of people, ideas, and goods. It created a place for different cultures to meet and talk. This happened on the ships, in Chinese capitals, and at banquets for foreign visitors. People from different countries met and traveled together. For the first time, the sea region from China to Africa was under one powerful empire. This created a diverse space.

Another goal was to keep political and cultural control in the region. Other countries needed to accept China as the main power. They had to be friendly with neighbors and accept the tributary system. Foreign rulers had to show they respected China's superior culture. They did this by paying respects and giving gifts. The Chinese wanted to "civilize" foreign peoples. They wanted to bring them into China's world order. One inscription says they captured or defeated those who resisted Chinese culture. This made the sea routes safe and peaceful.

Diplomatic relations were based on profitable trade and China's strong navy. China's naval power was key. It was not wise to risk punishment from the Chinese fleet. The fleet showed China's power and wealth. It aimed to impress foreign lands. This was done by showing the Ming flag and having a military presence. Also, the Chinese trade was profitable for foreign countries. This encouraged them to cooperate. Even though the Chinese fleet showed military might, they often sent smaller groups of ships. These groups focused on trade to build friendly relations.

One theory, which is very unlikely, says the voyages were to find the dethroned Jianwen Emperor. This reason is mentioned in a later historical work. Another unlikely theory is that the voyages were a response to the Timurid state under Tamerlane. Tamerlane was an enemy of Ming China. But after Tamerlane died in 1405, the new Timurid ruler made peace with China. Both theories are not accepted because there is no strong proof in old records.

Policies and Management

In the Ming court, civil officials were against the treasure voyages. They said the expeditions were too expensive and wasteful. But the Yongle Emperor didn't care about the costs. He was determined to do them. In contrast, the eunuch establishment led the treasure fleet. Civil officials were usually against the eunuchs and the military. This political difference made them oppose the voyages. Also, civil officials criticized the costs of building the fleet. But the emperor was set on building it. Eunuchs usually managed building projects. They supervised the fleet's construction, and the military carried it out. Civil officials also disliked the voyages for cultural reasons. They felt that trade and getting strange foreign goods went against their Confucian ideologies. These expeditions could only continue as long as the eunuchs had the emperor's favor.

The Hongwu Emperor started a ban on private sea trade in 1371. He was worried about the problems sea trade could bring. This policy continued into the Yongle reign. The Yongle Emperor also wanted to control sea trade. He wanted to stop coastal crime and disorder. He also aimed to provide jobs for sailors and traders. He wanted to export Chinese goods and import desired goods. He also wanted to expand the tributary system and show China's power. He made some changes to the tributary system. He encouraged state-run foreign trade. This led to the reopening of maritime offices in Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Ningbo. It also expanded tributary relations. For example, foreign envoys got tax breaks for private trade. The treasure voyages acted as trade missions. They helped the government control sea trade by creating an imperial monopoly. They also brought trade into the tributary system. One historian says there was an idea for foreign policy. It included expanded foreign trade, supported by a strong navy, and shared interests with local friends.

The Yongle Emperor was most interested in the first three voyages. But after moving the capital to Beijing, he focused more on his military campaigns against the Mongols. By the fourth voyage, he wanted to expand trade and diplomacy to West Asia. So, the Chinese looked for Persian or Arabic interpreters, like Ma Huan, to join the fleet. After the capital moved to Beijing, emperors and officials paid less attention to the south and the seas. The Hongxi Emperor wanted to move the capital back to Nanjing. But he died before he could. The Xuande Emperor, who followed him, stayed in Beijing. One historian notes that the voyages might have continued if the capital had moved back to Nanjing. This is because the court would have been closer to where the voyages started and where the ships were built.

The Hongxi Emperor ordered the voyages to stop on September 7, 1424. This was the day he became emperor. He personally disliked the sea expeditions. He had good relations with senior civil officials. He often sided with them when they opposed his father's plans. In particular, Minister of Finance Xia Yuanji was strongly against the voyages. In contrast, the Xuande Emperor went against the general court opinion when he ordered the seventh voyage. He relied on eunuchs during his rule.

People and Organization

The Chinese treasure fleet had many types of ships. Each ship had a special job. The treasure ships were the largest. They were like floating markets, full of products. Each treasure ship had about 500 to 600 men. Smaller ships were used by traders to go ashore. Larger ships stayed anchored in the harbor. Some ships were specifically for carrying water.

The fleet had seven Grand Directors and ten Junior Directors. Grand Directors, like Zheng He, were ambassadors and commanders. Junior Directors were their top assistants. In total, 70 eunuchs led the fleet. Below them were two brigadiers, 93 captains, 104 lieutenants, and 103 sub-lieutenants. There were also judges for military offenses.

The crew also included 180 medical staff. There was a finance officer, two secretaries, and two protocol officers. These protocol officers handled foreign envoys. An astrological officer and four astrologers were also on board. The rest of the crew included petty officers, soldiers, and various workers. These workers included boatmen, buyers, and clerks. Religious leaders from different faiths, like Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam, also served in the fleet.

Records from stone tablets mention Zheng He and Wang Jinghong as the main envoys. Other deputy envoys included Zhu Liang, Zhou Man, Hong Bao, Yang Zhen, Zhang Da, Li Xing, and Wu Zhong. All these envoys were Grand Directors.

For the first voyage, the fleet had 27,800 or 27,870 men. It included 317 ships, with 62 or 63 treasure ships. For the second voyage, the fleet likely had 249 ships. The exact number of treasure ships or crew is unknown.

For the third voyage, records say the fleet had 48 large ships and over 27,000 crew members. These 48 ships were likely treasure ships. They were probably built in 1408. The fleet also had other support ships.

For the fourth voyage, there were 63 treasure ships. They were accompanied by support ships. The crew numbered 28,560 or 27,670 men.

There are no records for the number of ships or crew for the fifth voyage.

For the sixth voyage, 41 treasure ships were ordered in 1419. These were likely used for this voyage. The fleet probably used dozens of treasure ships, each with several support vessels.

For the seventh voyage, records mention over a hundred large ships. These likely included most of the remaining treasure ships, plus support ships. The fleet had 27,550 men. Some ships were named, like Qinghe and Huikang. Others were just numbered.

Military Actions

Before the Ming treasure voyages, there was a lot of trouble at sea. Pirates, bandits, and slave traders caused problems near China's coast and in Southeast Asia. The Chinese treasure fleet had many warships. They protected their valuable cargo and secured the sea routes. They created a strong Chinese military presence in the South China Sea and in trading cities in southern India. The early voyages especially focused on military goals. They made the sea passages safe and strengthened China's position. Even though Zheng He sailed with a military force much larger than any local power, there's no clear proof they tried to control trade by force. However, the huge Chinese fleet would have been a "terrifying sight" for foreign nations. Its presence alone could make states cooperate.

The fleet fought and defeated pirate leader Chen Zuyi in Palembang. They also defeated Alakeshvara's forces in Ceylon and Sekandar's forces in Semudera. These battles brought safety and stability to the sea routes under Chinese control. These enemies were seen as threats. The battles reminded countries along the routes of China's great power. The Strait of Malacca was a very important link to the Indian Ocean. Controlling this area was key for China to be the top power in maritime Asia. It also helped them develop trade relations. Here, the fleet fought pirates to secure the region.

In Malacca, the Chinese actively worked to create a trade center and a base for voyages into the Indian Ocean. Malacca was a small region before the voyages. In 1405, China sent Zheng He with a stone tablet. This tablet made Malacca a country. The Chinese also built a government depot there. This was a fortified camp for their soldiers. It stored goods as the fleet traveled. Records say Siam did not dare to invade Malacca after this. Malacca's rulers, like King Paramesvara, would visit the Chinese emperor in person. In 1431, when a Malaccan representative complained that Siam was blocking tribute missions, the Xuande Emperor sent Zheng He with a strong message for the Siamese king. He told the king to respect his orders, have good relations with neighbors, and not act recklessly.

On the Malabar coast, Calicut and Cochin were rivals. So, the Ming decided to help Cochin. They gave Cochin and its ruler special status. For the fifth voyage, Zheng He was told to give a special seal to Cochin's ruler. He also named a mountain in Cochin the "Mountain Which Protects the Country." He delivered a stone tablet with a message from the Yongle Emperor. As long as Cochin was protected by China, the Zamorin of Calicut could not invade. This avoided military conflict. When the voyages stopped, the Zamorin of Calicut did invade Cochin.

Trade and Diplomacy

The Chinese treasure fleet carried three main types of goods. First, gifts for rulers. Second, items for trade or payment, like gold, silver, and paper money. Third, items China controlled, like musks, ceramics, and silks. It's said that sometimes so many Chinese goods were unloaded in an Indian port that it took months to price them all. In return, Zheng He brought back many tribute goods. These included silver, spices, precious stones, ivory, and exotic animals like ostriches and giraffes.

The imports from the Ming treasure voyages brought many goods that helped China's own industries. For example, there was so much cobalt oxide from Persia that China's porcelain industry had plenty for decades. The fleet also brought back so much black pepper that it became a common item in China. At the same time, large exports during the voyages helped Chinese industries grow and opened up overseas markets.

Imperial messages were sent to foreign kings. They could either accept China's friendship and receive rewards, or refuse and face China's strong military. Foreign kings had to show respect to the Chinese emperor by giving gifts. Many countries became China's friends. The fleet transported many foreign envoys to China and back.

Geography and Society

The Chinese treasure fleet sailed in the warm waters of the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. They depended on the yearly monsoon winds. So, the fleet's navigators carefully planned the voyages based on these wind patterns. For the trip south from Changle in China to Surabaya in Java, the fleet followed the northeast wind. They crossed the Equator, where the wind changes to northwest, and followed that. In Java, they waited for the tropical southeast wind to sail towards Sumatra. In Sumatra, they stopped because the wind changed to a strong southwest wind. They waited until the next winter for the northeast wind. For the trip northwest towards Calicut and Hormuz, the Chinese used the northeast wind. The return journey was planned for late summer and early autumn when the winds were favorable. The fleet left Hormuz before the southwest monsoon arrived. They used the northern wind for the trip from Hormuz to Calicut. For the eastward journey from Sumatra, the fleet used the new southwest monsoon. After passing through the Strait of Malacca, the fleet caught the southwest wind over the South China Sea to sail back to China. Because of the monsoon winds, smaller groups of ships often left the main fleet to go to specific places. The first split was in Sumatra, where a group would go to Bengal. The second split was in Calicut, where ships sailed to Hormuz and other places in the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa. Malacca was the meeting point where all the groups would gather for the final part of the return journey.

On all voyages, the fleet left Sumatra to sail west across the Indian Ocean. Northern Sumatra was an important place for the fleet to anchor and gather. This was before they went through the Indian Ocean to Ceylon and southern India. Its location was more important than its wealth or products. One writer said that Semudera, in northern Sumatra, was the main route to the Western Ocean. He called it the most important gathering port for the Western Ocean. The journey from Sumatra to Ceylon took about two to four weeks without seeing land. The first part of Ceylon they saw was Namanakuli Mountain. Two or three days after seeing it, the fleet sailed south of Dondra Head in Ceylon. After a long time at sea, the fleet arrived at a port in Ceylon, usually Beruwala or sometimes Galle. The Chinese preferred Beruwala. One writer called Beruwala "the wharf of the country of Ceylon."

Calicut was a main destination throughout the voyages. It also served as a transit point for places further west on later voyages. Ming China had good relations with Calicut. This was important as they tried to extend the tributary system to states around the Indian Ocean. One writer described Calicut as the "great country of the Western Ocean." He liked how Calicut's leaders managed trade. Another writer called Calicut the "great harbor" of the Western Ocean countries.

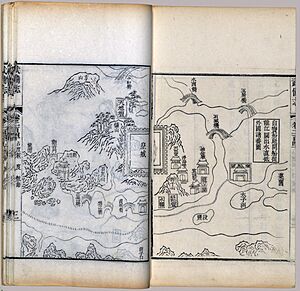

During the Ming treasure voyages, the Chinese fleet gathered a lot of navigation information. This was recorded by the astrological officer and his four astrologers. This information was used to create different types of maps by a special office. This office included the astrological officer, astrologers, and their clerks. They gave the commanders the maps they needed for their journeys. Many copies of these maps were kept in the Ministry of War. Local maritime pilots, Arab records, Indian records, and other Chinese records also likely provided navigation information.

The fleet's navigators and pilots were called huozhang. If they were foreigners, they were called fanhuozhang. They used tools like compasses. These navigators and pilots were mentioned in records for their help in battles. These included battles at Palembang and Ceylon. They also helped in a fight against Japanese pirates.

The Mao Kun map shows the routes the fleet took during the voyages. It's part of a book called the Wubei Zhi. It shows many places from Nanjing to Hormuz and the East African coast. The routes are shown with dotted lines. The map is thought to be from about 1422. It likely combines navigation data from the 1421–1422 expedition. Directions are given by compass points. Distances are given in watches (time periods). It also mentions navigation techniques like depth sounding to avoid shallow waters. And it uses astronomy, especially for the north-south route of Africa. Here, the ship's position was found by looking at the height of stars above the horizon. The Mao Kun map also has four star diagrams. These were used to find the ship's position based on stars and constellations.

Beliefs and Ceremonies

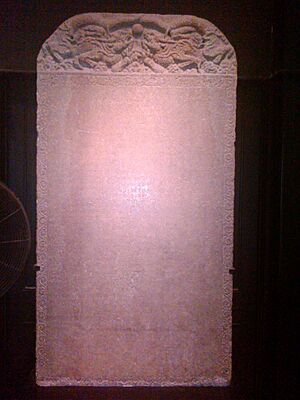

The Chinese treasure fleet's crew believed in Tianfei. She was the "Heavenly Princess," the goddess of sailors. Stone inscriptions at Liujiagang and Changle honored this goddess. They mention the crew seeing Saint Elmo's fire during storms. They believed this was a sign of Tianfei's divine protection. Zheng He and his friends put up these inscriptions at Tianfei's temples in 1431 and 1432. The inscriptions suggest that Zheng He's life was mostly about the treasure voyages. His strong belief in Tianfei was his main faith. These inscriptions are seen as summaries of the voyages.

In Galle, Ceylon, Zheng He set up a three-language inscription on February 15, 1409. The Chinese part praised the Buddha. The Tamil part praised the local god Tenavarai Nayanar (a form of Vishnu). The Persian part praised Allah. Each part lists similar offerings. These included gold, silver, silk, perfumed oil, and bronze ornaments. This inscription shows that the Chinese respected the three main religions in Ceylon.

On September 20, 1414, envoys from Bengal presented a giraffe as a gift to the Yongle Emperor. They said it was a qilin, a mythical creature. But the emperor probably didn't think it was a qilin.

Confucianism shaped how the Chinese viewed the outside world during the voyages. The Chinese did not try to make the places they visited Confucian. This was different from Europeans who tried to spread Christianity. In the Confucian worldview, different religions are recognized. This is because all people can understand heavenly principles through their reason. Confucians believe that societies should develop their own unique ways. This would lead to a peaceful world. They knew that Confucian society had limits. They also believed that human nature is good. This means people have a natural ability to follow heavenly principles. Finally, in Confucian tradition, history is seen as a cycle of order and disorder. This is different from ideas about an end of the world. This gave them a calm way of thinking.

Historical Records

There are several important records from the time of the voyages. These include Ma Huan's Yingya Shenglan, Fei Xin's Xingcha Shenglan, and Gong Zhen's Xiyang Fanguo Zhi. These three books are important because their authors were actually on the expeditions. Ma Huan was an interpreter on the fourth, sixth, and seventh voyages. Fei Xin was a soldier on the third, fifth, and seventh voyages. Gong Zhen was Zheng He's private secretary on the seventh voyage. These three sources describe the politics, economy, society, culture, and religions of the lands visited. Also, the stone inscriptions at Liujiagang and Changle are valuable records. They were written by Zheng He and his friends.

The Ming Shilu (True Records of the Ming) provides much information about the voyages. Especially about the exchange of ambassadors. Zheng He lived during the reigns of five Ming emperors. But he served three directly. He is mentioned in the records of the Yongle, Hongxi, and Xuande reigns. The Taizong Shilu combined the second and third voyages into one. This mistake was repeated in the Mingshi (History of Ming). This led to Zheng He's trip to Palembang in 1424–1425 being wrongly called the sixth voyage. But the Liujiagang and Changle inscriptions clearly separate the second and third voyages. They correctly date the second from 1407 to 1409 and the third from 1409 to 1411.

Many later books also talk about the voyages. These include the Mingshi (1739) and other works from the 1500s and 1600s. Zhu Yunming's Xia Xiyang (Down the Western Ocean) gives a detailed plan of the seventh voyage. Mao Yuanyi's Wubei Zhi (1628) has the Mao Kun map. This map is based on information from the voyages. One record from 1553 says that the plans for the treasure ships had disappeared from the shipyard.

A novel from 1597, Sanbao Taijian Xiyang Ji Tongsu Yanyi, tells a story about Zheng He's adventures. In this novel, Zheng He searches for a sacred imperial seal. The novel describes different types of ships and their sizes. However, historians say this novel is not a reliable historical source.

Some records describe what happened to the official documents about the expeditions. During the reign of the Chenghua Emperor (1465–1487), an order was given to find the documents about the Western Ocean expeditions. But an official named Liu Daxia had hidden and burned them. He said the accounts were "deceitful exaggerations." He felt the expeditions wasted too much money and lives. He believed they brought no real benefit to the state. He thought they were a sign of bad government. He said the records should be destroyed to prevent such things from happening again. Another official was reportedly impressed by this explanation.

Some sources say the records were destroyed to stop a eunuch named Wang Zhi from using them for an invasion of Vietnam. However, some historians doubt Liu Daxia's involvement. They also suggest the documents might have been lost when Beijing was captured by rebels in the 1600s.

Historians also look at records from Southeast Asia. These can give information about the voyages. But their accuracy needs to be checked. Local stories can mix with legends. Arabic sources also provide details. They give dates for the fleet's arrival and events in the Arabian region. They also give information about trade goods. For example, one Arabic text describes Chinese ships reaching Aden in 1419. Another describes a meeting between a Rasulid Sultan and Chinese envoys. This shows how a non-Chinese ruler willingly followed the tribute rules.

Lasting Impact

In 1499, before Vasco da Gama returned from India to Portugal, he heard stories. People said "certain vessels of white Christians" had visited Calicut generations before. He wondered if they were Germans or Russians. After arriving at Calicut, da Gama heard tales of pale, bearded men. They sailed giant ships along the coast many years ago. The Portuguese had found local stories that remembered Zheng He's voyages. But they didn't know these tales were about his fleet. Da Gama's men were even mistaken for the Chinese when they arrived on the East African coast. This was because the Chinese were the last pale-skinned strangers to arrive in large wooden ships.

In the late 1500s, Juan González de Mendoza wrote that it was clear the Chinese had come to the Indies. They had conquered everything from China to the furthest part. He said there was still a strong memory of them. He also mentioned that in Calicut, there were many trees and fruits. Locals said the Chinese brought them when they ruled the country.

Many Chinese people today believe these expeditions followed Confucian ideals. In 1997, Chinese President Jiang Zemin praised Zheng He for spreading Chinese culture. Since 2005, China celebrates its National Maritime Day on July 11. This day marks the 600th anniversary of Zheng He's first voyage.

Today, people often say the voyages were peaceful. They point out there was no land conquest or colonization. But this overlooks the fleet's strong military power. This power was used to show China's strength and promote its interests. In today's Chinese politics, with China's growing sea power, the voyages are used to show a peaceful rise of modern China. By comparing modern China to these historical voyages, it helps build national pride. It shapes national identity and confirms China's maritime identity. It also justifies developing sea power. It presents an image of peaceful development and highlights connections with the world. It also contrasts with the violent nature of Western colonialism. So, the voyages are important in China's promotion of maritime power and soft power diplomacy.