Volta Laboratory and Bureau facts for kids

|

Volta Bureau

|

|

|

|

| Location | 3414 Volta Pl., NW Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Built | (1885) 1893 |

| Architect | Peabody and Stearns |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001436 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | November 28, 1972 |

| Designated NHL | November 28, 1972 |

The Volta Laboratory and the Volta Bureau were important places created by Alexander Graham Bell in Georgetown, Washington, D.C.. Bell is famous for inventing the telephone.

The Volta Laboratory started around 1880. Bell worked there with Charles Sumner Tainter and his cousin, Chichester Bell. They researched telecommunication, phonographs, and other cool technologies.

Later, Bell used money from the Volta Laboratory's success to start the Volta Bureau in 1887. Its goal was to share knowledge and help people who were deaf. The Bureau later joined with another group and is now called the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

Contents

Alexander Graham Bell's Work

The building you see today is a U.S. National Historic Landmark. It was built in 1893 under Bell's guidance. He wanted it to be a hub for information for deaf and hard of hearing individuals.

Bell is best known for getting the first telephone patent in 1876. But he was also a leading figure in educating the deaf. His family had a long history of teaching speech.

Bell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. He moved to Canada in 1870 and then to Boston in 1871. In Boston, he taught at a special school for deaf children. Both his mother and wife were deaf, which deeply influenced his life's work. He became a respected educator.

He also invented many things during this time. These included an improved phonautograph, the multiple telegraph, and, of course, the telephone.

How the Volta Bureau Started

In 1879, Bell and his wife, Mabel Hubbard, moved to Washington, D.C. Mabel had been deaf since she was a child.

The next year, the French government gave Bell the Volta Prize. This was a large sum of money, about US$10,000 in 1879, for inventing the telephone. Bell used this money to create the Volta Fund.

He then founded the Volta Laboratory Association. His cousin Chichester A. Bell and Sumner Tainter joined him. The lab focused on studying, recording, and sending sound.

In 1887, the Volta Laboratory Association sold their sound recording patents. Bell used some of his profits to start the Volta Bureau. He wanted it to be a place "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf."

The Volta Bureau worked closely with the American Association for the Promotion of the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (AAPTSD). Bell was elected president of this group in 1890. The Volta Bureau officially merged with the AAPTSD in 1908. Today, it is known as the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

From Lab to Bureau Building

Bell's early research in Washington, D.C., happened in rented houses. The lab moved a few times. With his associates doing much of the lab work, Bell focused on deafness research. This led him to create the Volta Bureau in 1887.

For a few years, the Volta Bureau was in the carriage house behind Bell's father's home. But the Bureau's work grew so much that Bell needed a bigger space. In 1893, he built a new, special building for it.

This new building was across the street from his father's house. On May 8, 1893, Helen Keller, who was 13 years old, helped break ground for the new building.

The 'Volta Bureau' got its name in 1887 from John Hitz, its first superintendent. Bell also renamed his Volta Fund to the Volta Bureau Fund. He donated a lot of money to organizations helping the deaf.

The building itself is a beautiful neoclassical style. It was designed by Peabody and Stearns of Boston. It became a National Historic Landmark in 1972.

Even after creating the Volta Bureau, Bell continued his scientific work. He built a larger lab in Nova Scotia. Bell always called himself a "teacher of the deaf." But he was also a great inventor and scientist.

In 1895, Bell's father, Alexander Melville Bell, gave all his book copyrights to the Volta Bureau. This helped the Bureau financially. The Volta Bureau continues its important work today as the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

Amazing Lab Projects

The Volta Laboratory Association, or Volta Associates, was officially formed in 1881. It owned the patents for their inventions. The group included Alexander Graham Bell, Charles Sumner Tainter, and Bell's cousin, Dr. Chichester Bell.

In the 1880s, the Volta Associates worked on many projects. At first, they focused on telephone ideas. But then they shifted to improving the phonograph. Here are some of their cool projects:

- the 'intermittent-beam sounder' – used to study sounds and create pure tones (1880).

- the Photophone – a wireless telephone that used light. It was an early version of fiber-optic communication (1880).

- experiments in magnetic recording – trying to record sounds onto electroplated records (1881).

- an artificial respirator called a "vacuum jacket." Bell created it after one of his baby sons died from lung problems (1881).

- the 'spectrophone' – a Photophone version used for spectral analysis with sound (1881).

- an improved induction balance – a metal detector made to try and save President James A. Garfield's life (1881).

- a 'speed governor' for record players (1882).

- the 'air-jet record stylus' – an electric-pneumatic stylus to reduce background noise on records (1885).

- an audiometer – used to help study deafness.

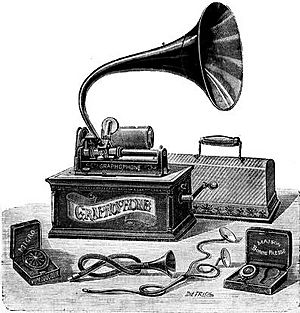

They also made many other important improvements to the phonograph. They even created the name for one of their products – the Graphophone.

Tainter Joins the Lab

Bell met Charles Sumner Tainter, a talented instrument maker. Bell asked Tainter to move to Washington to help start the new laboratory. Bell's cousin, Chichester Bell, also joined them.

Tainter later wrote about setting up the lab:

I packed up all my tools and machines, and... went to Washington. I rented a vacant house... and set it up for our work... We were like explorers in an unknown land... We had to design experimental tools, find materials, and build our own models.

Bell didn't spend all his time in the lab. He suggested ideas and provided money. His associates often got credit for many of the inventions. The lab built different types of phonographs, including disc and cylinder machines. They even made a hand-powered, non-magnetic tape recorder.

These old records and tapes are now at the Smithsonian Institution. They are some of the oldest real sound recordings in the world.

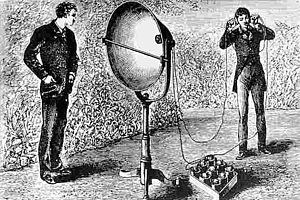

The Photophone: Wireless Light Communication

The Photophone was invented by Bell and Sumner Tainter in 1880. Bell thought it was his most important invention. This device could send sound on a beam of light.

On April 1, 1880, Bell's assistant sent the world's first wireless telephone message to him. It was sent from the Franklin School to Bell's lab window, about 213 meters away. This was a very early step towards fiber-optic communications.

Bell received four patents for the Photophone. He called it his "greatest achievement," even "greater than the telephone."

Bell transferred the Photophone's rights to the National Bell Telephone Company in May 1880. The main patent for the Photophone was issued in December 1880. It was many decades before this technology could be used in real-world products.

Improving Sound Recording and the Phonograph

The Challenge of Early Recording

Bell and his team took Thomas A. Edison's early tinfoil phonograph and made it much better. Edison's machine recorded sound onto tinfoil. It was hard to use, the tinfoil tore easily, and the sound was often distorted. Edison didn't improve it much because he was busy with his electric light system.

Bell, however, loved to experiment. Gardiner Hubbard, Bell's father-in-law, was interested in phonograph technology. Hubbard's company, which owned Edison's patent, was losing money because the machine didn't work well.

So, in 1879, Hubbard convinced Bell to try and improve the phonograph. They decided to create a lab in Washington, D.C.. They also worked on other communication ideas, like sending sound with light, which led to the Photophone.

The Graphophone: A Better Way to Record

By 1881, the Volta Associates had greatly improved Edison's phonograph. Instead of tinfoil, they filled the cylinder's groove with wax. Then, they used a sharp tool to engrave the sound into the wax, not just indent it. This made the sound much clearer.

They sealed their first improved machine in a metal box and put it in the Smithsonian archives in 1881. This was to protect their invention in case of patent disputes.

In 1937, the box was finally opened. A recording was found on the wax-filled cylinder. A voice from the past spoke, quoting Shakespeare: "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy..." The voice also playfully said: "I am a Graphophone and my mother was a Phonograph."

Bell's daughter thought it was her father's voice. But Charles Sumner Tainter later confirmed it was Bell's father, Alexander Melville Bell. This historic recording, unheard since 1937, was played again in 2013 and is now available online.

The machine used a unique way to play back sound: a jet of high-pressure air. Tainter wrote in 1881 that the words could be heard from at least 8 feet away!

Most of the disc machines at the Volta Lab had their discs spinning vertically. This was because they were first tested on a shop lathe.

The Bell and Tainter records used both "lateral cut" (side-to-side waves) and "hill-and-dale" (up-and-down waves) styles. While Emile Berliner is known for the lateral cut Gramophone record in 1887, the Volta associates experimented with both types as early as 1881.

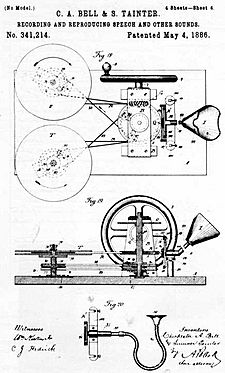

The main difference between Edison's first phonograph and the Bell and Tainter patent of 1886 was how they recorded. Edison indented sound waves on tinfoil. Bell and Tainter engraved them into wax. They always looked for the best materials to get the clearest sound.

Edison eventually had to admit that his "new phonograph," which used wax, copied Bell and Tainter's idea. He even had to get a license from them to make his records.

The Graphophone used a sharp stylus to cut lateral "zig-zag" grooves into wax-coated cardboard cylinders. Edison's machines used up-and-down grooves on tinfoil.

Bell and Tainter's wax-coated cardboard cylinders were much easier to handle and allowed for longer, better-quality recordings. Their Graphophones also used clockwork or electric motors, which were much better than Edison's hand crank. These improvements made the Graphophone's sound quality much better.

Magnetic Sound Recordings

The Volta Lab scientists also experimented with magnetic recording. In 1881, they thought about using a fountain pen with iron ink to trace a spiral line on paper. The ink would become magnetic, and a magnet could then play back the sounds. This idea led to a patent in 1886 for "reproduction, through the action of magnetism, of sounds by means of records in solid substances."

Optical/Photographic Recordings

They also tried optical recordings on photographic plates.

The Tape Recorder

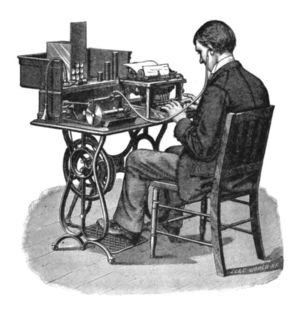

Two of the Volta associates patented a non-magnetic, non-electric, hand-powered tape recorder in 1886. It used a narrow strip of paper coated with beeswax and paraffin.

The machine was made of wood and metal and powered by a hand knob. The tape moved from one reel to another, passing a recording or playback stylus. A sharp stylus, moved by a sound-vibrated mica diaphragm, engraved a groove into the wax. For playback, a dull stylus rode in the groove, and the sound was heard through rubber listening tubes, like a stethoscope.

This machine was never sold commercially. But it's interesting because it looks like later magnetic tape recorders.

Selling the Phonograph Patents

In 1885, the Volta Associates felt their inventions were ready. They applied for patents and looked for investors. They got Canadian and U.S. patents for the Graphophone in 1885 and 1886. The Graphophone was first meant for businesses as a dictation recording and playback machine.

The Graphophone Company was created in 1886 to manage the patents and develop the inventions. One of these inventions became the first Dictaphone.

After demonstrations, businessmen from Philadelphia formed the American Graphophone Company in 1887. This company would produce the machines. The Volta Graphophone Company then merged with American Graphophone. This company later became Columbia Records, which is now part of Sony. Bell received about US$200,000 from this deal. He used $100,000 to fund the new Volta Bureau's research and programs for the deaf.

The Howe Machine Factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, became the first American Graphophone factory. Charles Sumner Tainter supervised manufacturing there. This small factory later became the Dictaphone Corporation.

Jesse H. Lippincott later bought control of American Graphophone and the Bell and Tainter patents. He also bought Edison's company and created the North American Phonograph Company. However, the machines had mechanical problems, and stenographers resisted them. This delayed the Graphophone's popularity until 1889.

The work of the Volta Associates was very important. Their wax recording process was practical, and their machines were strong. This laid the groundwork for successful dictating machines in business. But it took more effort from Thomas Edison, Emile Berliner, and others for the recording industry to become a big part of home entertainment.

Legacy and Impact

In 1887, the Volta Associates sold their sound-recording patents to the American Graphophone Company. Bell used his profits to found the Volta Bureau. He wanted it to be a place "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf." He also used the money for other good works related to deafness. His research on deafness grew so much that it filled a whole room in the Volta Laboratory.

Because of the limited space, Bell built the new Volta Bureau building in 1893. His father helped him with the cost.

Under John Hitz, the Volta Bureau became a top center for research on deafness and teaching methods for the deaf. Bell's Volta Bureau worked closely with the American Association for the Promotion of the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (AAPTSD). Bell was its president. The Volta's research was later included in the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf (now 'AG Bell') when it merged with the AAPTSD in 1908.

The history of the Volta Laboratory became clearer in 1947. Laura F. Tainter, Sumner Tainter's widow, donated ten volumes of his Home Notes to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History. These daily books described the projects at the lab in the 1880s.

In 1950, Laura Tainter donated more historical items. These included Sumner Tainter's autobiography, which detailed his experiences at the lab and factory.

Hearing Bell's Voice

Alexander Graham Bell died in 1922. For a long time, no recordings of his voice were known to exist. But on April 23, 2013, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History made an exciting announcement.

They have a collection of Volta Laboratory materials. Using a special optical scanning technology called IRENE, they could safely play a fragile wax-on-cardboard disc. This disc had preserved the inventor's voice, with his Scottish accent!

Scientists also brought back the voice of Bell's father, Alexander Melville Bell. This was from an 1881 recording on a modified Edison tinfoil cylinder phonograph.

Both Bells helped test some of the Volta Laboratory's experimental recorders. The disc recording is 4 minutes and 35 seconds long. It's mostly a recitation of numbers. It's dated April 15, 1885. It ends with Bell's clear spoken signature: "Hear my voice. ... Alexander. . Graham. . Bell."

A biographer, Charlotte Gray, described Bell's voice. She said it showed his clear speaking style. This was thanks to his father, a famous speech teacher. It also showed his careful way of speaking for his deaf wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard, who relied on lip reading. Gray noted that Bell's British accent was clear. His voice sounded strong and direct, just like the inventor himself, speaking to us from the past.

Location

The Volta Bureau is located at 3417 Volta Place NW in the Georgetown area of Washington, D.C. It's near Georgetown University and close to the Foggy Bottom Metro subway stop.

Laboratory Patents

Here are some of the patents that came from the Volta Laboratory Association's work:

| Patent | Year | Patent name | Inventors |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Patent 229,495 | 1880 | Telephone call register | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 235,496 | 1880 | Photophone transmitter | A. G. Bell C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 235,497 | 1880 | Selenium cells | A. G. Bell C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 235,590 | 1880 | Selenium cells | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 241,909 | 1881 | Photophonic receiver | A. G. Bell C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 243,657 | 1881 | Telephone transmitter | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 289,725 | 1883 | Electric conductor | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 336,081 | 1886 | Transmitter for electric telephone lines | C. A. Bell |

| U.S. Patent 336,082 | 1886 | Jet microphone for transmitting sounds by means of jets | C. A. Bell |

| U.S. Patent 336,083 | 1886 | Telephone transmitter | C. A. Bell |

| U.S. Patent 336,173 | 1886 | Telephone transmitter | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 341,212 | 1886 | Reproducing sounds from phonograph records | A. G. Bell C. A. Bell C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 341,213 | 1886 | Reproducing and recording sounds by radiant energy | A. G. Bell C. A. Bell C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 341,214 | 1886 | Recording and reproducing speech and other sounds | C. A. Bell C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 341,287 | 1886 | Recording and reproducing sounds | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 341,288 | 1886 | Apparatus for recording and reproducing sounds | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 374,133 | 1887 | Paper cylinder for graphophonic records | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 375,579 | 1887 | Apparatus for recording and reproducing speech ... | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 380,535 | 1888 | Graphophone | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 385,886 | 1888 | Graphophone | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 385,887 | 1888 | Graphophonic tablet | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 388,462 | 1888 | Machine for making paper tubes | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 392,763 | 1888 | Mounting for diaphragms for acoustical instruments | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 393,190 | 1888 | Tablet for use in graphophones | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 393,191 | 1888 | Support for graphophonic tablets | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 416,969 | 1889 | Speed regulator | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 421,450 | 1890 | Graphophone tablet | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 428,646 | 1890 | Machine for the manufacture of wax coated tablets ... | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 506,348 | 1893 | Coin controlled graphophone | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 510,656 | 1893 | Reproducer for graphophones | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 670,442 | 1901 | Graphophone record duplicating machine | C. S. Tainter |

| U.S. Patent 730,986 | 1903 | Graphophone | C. S. Tainter |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Laboratorio Volta para niños

In Spanish: Laboratorio Volta para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |