2007 vole plague in Castile and León facts for kids

The 2007 vole plague started in the summer of 2006 in a part of Spain called Castile and León, specifically in the province of Palencia. This problem became very noticeable from the summer of 2007. Tiny rodents, called voles, ruined farm fields, especially those with irrigation. By September 2007, the number of voles went down, and people thought the plague was over. However, many voles were still around for months. It was only the cold winter weather and low temperatures in November and December that finally helped stop the problem.

The common vole (Microtus arvalis) was the animal that destroyed the crops. These voles usually live in Europe and Asia. In Spain, they used to live only in the Cantabrian Mountains. But they started to spread south, away from their natural enemies like birds of prey. Normally, their population was around 100 million. But in the summer of 2007, it's thought they reached at least 700 million! They ruined about 500,000 hectares of crops and caused losses of 15 million euros. People even called them the scourge of Castile because they ate so much.

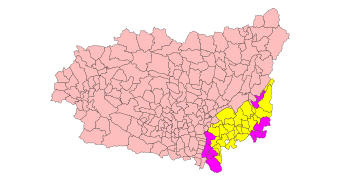

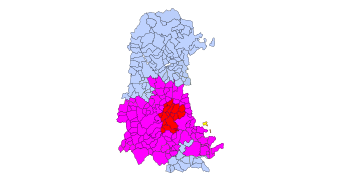

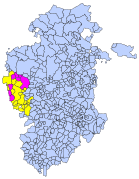

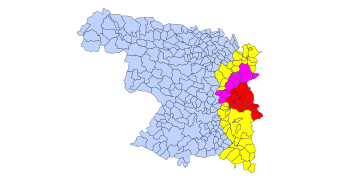

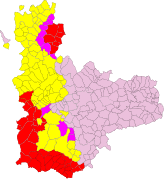

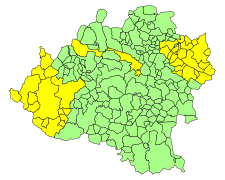

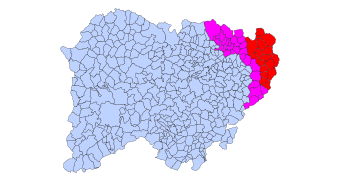

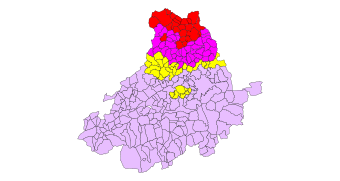

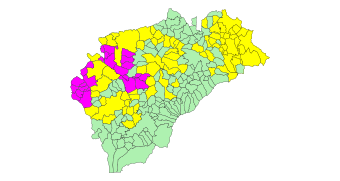

This vole plague affected all of Castile and León. The areas hit hardest were the provinces of Valladolid, Segovia, Palencia, and Zamora. This was especially true in places like Tierra de Campos and near Tierra de Medina, where other provinces like Salamanca and Avila meet. Voles were even found in towns near Portugal.

Contents

What Caused the Vole Plague?

Several things led to this huge increase in voles, which destroyed whole fields of crops like beets, potatoes, onions, and carrots.

Normally, winters in this part of Spain are very cold. But in 2007, temperatures were warmer than usual. There were almost no frosts. When spring arrived, it was also warmer than average. This warm weather helped the voles' population grow very quickly. These animals grow up fast and have many babies several times a year. This made their numbers explode easily.

Another reason for the voles spreading was a complaint from environmental groups in March 2007. They complained to the regional government, the Junta of Castile and León, about the poison being used to stop the early stages of the plague. A farmers' group, ASAJA, blamed the government and environmental groups. They said stopping the early prevention methods led to the big crisis.

Voles can also spread diseases to humans, like tularemia. This can happen through direct contact or by breathing in dust that touched the animals or their droppings. The plague might have caused 42 cases of this disease in the region, according to the government. Another political party, the PSOE, said the number could be as high as 270 cases. Because of this, the government even asked people not to eat wild game during hunting season, fearing they might get sick.

How Many Voles Were There?

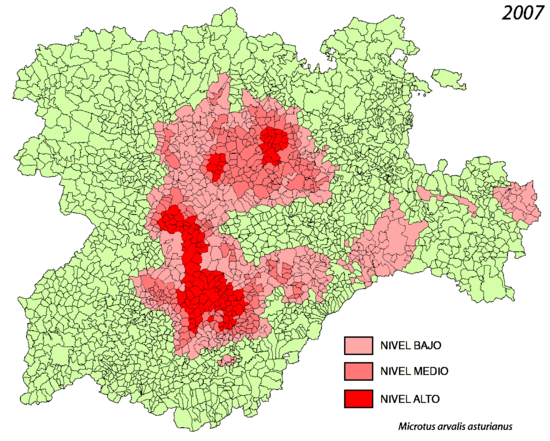

Normally, there are about 5 to 10 common voles in one hectare of land. But during the plague in Castile and León, some areas had up to 1,500 voles per hectare!

The province of Palencia, where the plague started, was the most affected. After that came Valladolid and Zamora. The province of Soria was the least affected.

High concentration Average concentration Low concentration

What Happened Because of the Vole Plague?

When vole populations explode, there are both good and bad effects on nature. For example, their burrows help the soil by adding organic matter like buried plants and their droppings. They also make the soil airy and spongy, which helps water soak in. Some scientists even said that having many voles in Castile and León over the years helped increase the variety of animals in the Douro Valley.

However, there are also harmful effects. One big worry is that voles can carry serious diseases that affect humans and other animals. The common vole is known to carry many diseases. These include viral diseases like rabies and hantavirus, and bacterial diseases like leptospirosis and tularemia. They can also carry protozoa and worms.

Having lots of easy prey helps predators (animals that hunt others) because they have plenty of food. But vole plagues don't last as long as the lives of most predators. So, when voles become scarce, predators might start hunting other animals. This can sometimes affect endangered species. For example, if foxes and martens eat many voles, their numbers grow. But when voles disappear, these predators might then hunt other birds, like grouse.

"Even though grouse breeding improved when there were many mice, it didn't have a lasting effect on their population size. Instead, there were fewer adult western capercaillie after the mouse population spikes. This might be because predators had more babies when mice were plentiful, and then killed more grouse in winter or early in the next breeding season."

For humans, these huge increases in vole numbers are harmful plagues. They cause many problems in different areas: money, fun activities, health, and society. They can even cause public worry, leading to political arguments.

Consequences for Crops

The common vole is thought to be the most damaging animal for farming, not just in Spain, but all over Europe. They mainly eat soft green plant stems, but also leaves and corn. The 2007 plague seemed to start in Tierra de Campos (Palencia) and spread across the region. It's estimated that over 200,000 hectares of land in Castile and León were affected, and losses might have been more than one million euros.

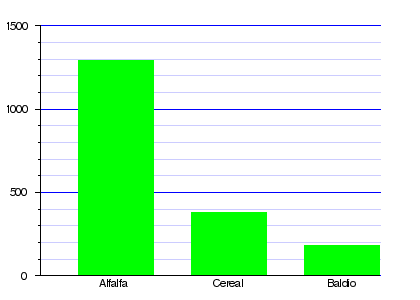

During the sowing season, voles make their homes in ditches and field edges, safe from plows. But after planting, they move into the fields. In cereal fields or pastures, they can create empty patches. In the United States, it was found that if there are about 200 voles per hectare, 5% of alfalfa crops are lost. Since the numbers in Spain were much higher, you can imagine how bad the damage was. In beet fields, they eat the tuber (the root), which makes the whole plant rot quickly. They also chew the stems of sunflowers until they fall. Voles even ate in vineyards, chewing on young shoots. If they damage the base of the vine, it can ruin harvests for years to come. Sometimes, the damage isn't clear until it's too late to fix. Fruit trees also get attacked. Voles chew the bark at the bottom of the trunks, which weakens or kills the trees.

Health Consequences

Rodents make up almost half of all known mammal species. They cause the most problems for humans and carry the most pathogens (germs that cause disease). This is called zoonosis, meaning diseases that can spread from animals to humans. As mentioned, common voles are very good at spreading these diseases, especially when there are many of them. This makes it easier for them to come into contact with people or animals like pets and farm animals.

Many health risks are linked to fun activities. These risks often get less attention than money losses. Plagues often happen during holidays. Many children and teenagers in rural areas saw huge numbers of voles in parks, gardens, and even kitchen gardens in towns. Voles are less aggressive and clumsy than house mice or rats, so people might think they are harmless. It became popular to chase, catch, or kill them for fun. But the danger is real. People can get serious diseases. Also, babies and small children might touch dead voles left on the grass or in sandboxes. Fleas, ticks, and other mites can live on these dead animals for a long time. Many voles also drown in swimming pools or irrigation ponds every night.

Another risk related to fun activities is small game hunting. The regional government had to publish tips to avoid problems from the plague. Before, people didn't worry much about this, thinking it was just a farmer's problem. But the idea of a poisoned dog, a hunter getting tularemia, or even being poisoned by rodenticides caused alarm. There was a lack of planning from both hunting groups and authorities. Everyone started blaming each other.

Government Actions

The regional government, the Junta of Castile and León, was slow to act as the plague spread. This led thousands of farmers to protest in the streets of Valladolid on August 2, asking for solutions.

Since the government wasn't acting, farmers started finding their own ways to fight the voles. They dug ditches and filled them with water so voles would fall in and drown. The town of Villalar de los Comuneros in Valladolid, with its mayor, even designed a plow to destroy vole burrows. But these efforts were not enough.

The first official solutions came late, on August 9, when voles were already in towns. The government allowed burning of stover (leftover crop stalks). The first town to do this was Fresno el Viejo in Valladolid.

The plague also spread to the wine world, causing an estimated 40% loss in grape harvests. This, plus losses in the animal farming sector, put the farming industry in Castile and León in a tough spot. Because of all this, many mayors in the area asked for their regions to be declared disaster zones.

Vole Plagues in Castile and León

Vole "plagues" were almost unknown in Spain until a few decades ago. The naturalist Juan Delibes de Castro said in 1989:

"In Spain, the common vole (Microtus arvalis) populations were very small and found only in certain mountain areas. However, in the last ten years, they have spread greatly, causing significant crop losses."

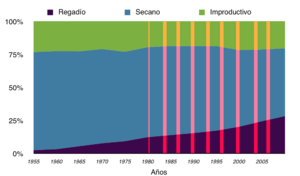

Studies in the 1970s showed this species only in the southern Cantabrian Mountains and in some other mountain ranges. It seems the species might have moved down river valleys where there was a lot of alfalfa. But since the early 1980s, there were reports of common voles in the province of Valladolid. This kind of spread was new for the Spanish Northern Plateau.

Since then, in the Douro valley, there have been huge increases in vole numbers every three or four years. They became a very harmful pest for farming. Normally, there are 5–10 voles per hectare. But during these overpopulation cycles, there were more than 200 voles per hectare. This is a low estimate, as the real numbers are hard to count. In October 1983, one study found up to 1294 voles per hectare in alfalfa fields, 382 in cereal fields, and 182 in badlands.

| Density of voles per hectare |

|

A specialist named Ángel María Arenaz believes it's possible to predict how big a vole problem will be by counting them in winter. If there are more than 50 voles per hectare in January, a dangerous level is likely in summer. But if the number is lower, there's probably no danger. This expert also says that forecasts can be made based on autumn rains: more rain is bad for vole reproduction. To make good predictions for a farming year, regular counts should be done using special traps in alfalfa fields in September, February, May, and August.

As naturalist Juan Carlos Blanco points out, "in Spain there is no information on the subject." We lack good data and don't even know why these population explosions happen, even though they repeat often.

Regarding the 2007 plague, which was one of the worst ever, the regional government provided information based on reports from local farming groups. These are just estimates, as there wasn't a full study. The vole problem was officially declared a plague on March 27.

Some people in rural areas even accused environmental groups of releasing voles from special farms to feed birds of prey. This idea is so strong that it's hard to explain to farmers that the plagues happen naturally. Fernando Franco Jubete explains this belief:

"...voles are creatures made in labs and grown by the millions on secret farms. Then they are released from mysterious SUVs and helicopters to feed birds of prey. So, the guilty ones are those who allow, pay for, and do this: "the Government", "the Environment", "ICONA", "the ecologists"."

It's true that many voles help all kinds of predators, not just their usual enemies like owls, weasels, and black-winged kite. Other general predators like dogs, cats, crows, storks, and herons also benefit. This means these predators hunt fewer other small animals like partridges, quails, and rabbits. But it also means the number of predators grows. Some animals that eat voles, like certain birds of prey, migrate or are not very picky eaters. So, if the voles disappear when these predators leave, there might be no big problem. But for predators that stay in one place, they have to find other food when voles become scarce. This can lead to them hunting more common prey, which is not good for those animals.

A large spread of voles must have started in an area where their population was already big and stable. Something must have made them spread, and they found good ways to move, like new roads or more irrigated fields in river valleys. Once they took over the Douro basin, the alfalfa fields, which they love, became safe places where the plague could start under the right conditions. Here are some ideas about what caused this to happen:

- Some experts think plants might affect how many babies animals have. The amount of land used for irrigation in the Douro Valley has grown a lot in the last 20 years. This is also when pests became more common. Alfalfa and sugar beet are big food sources for voles. However, big changes in population can only be explained by much better living conditions in very specific, non-repeating cases. Also, normally, "mice in large areas... eat only 1–2% of the available food. This is because insects eat much more plant material than these mammals."

- Another idea focuses on predators as a way to control the species. If there aren't enough enemies, their numbers can grow very fast. It's been shown that rodents can multiply hugely when there are few natural enemies. This is also linked to how rich the natural environment is: plagues are worse in poorer ecosystems. The few predators can't stop the population growth at first. But slowly, they react, having more babies and gathering where the voles are. The next year, the many carnivores (hunters) are enough to greatly reduce the vole population. As the voles are almost wiped out, predators have to change their diet. But there usually aren't enough other food sources, so the number of predators slowly goes down over a few years. This brings them back to a low level, which then allows a new vole population explosion.

- It's also suggested that the causes are internal to the voles themselves. Voles might change how they reproduce and behave socially, causing a huge increase or decrease in their population. Rodents have a great ability to reproduce, but this is usually kept in check, so their populations stay stable. Sometimes, though, they reproduce without limits. When this happens, there's tough competition for survival, like for space or food. Many voles might not fit in socially, lack a stable home, or have trouble finding food or reproducing. They are at the bottom of the colony's social ladder. So, internal ways within the population control their numbers. They change scent signals and communication, which mainly affects lower-ranking voles. This increases their stress. Rodents react to stress by making more Adrenaline, which reduces their ability to reproduce and makes them more likely to get the diseases they carry.

It's important to understand the difference between why voles spread from their original mountain environments to the Douro valley (where they weren't seen until the early 1980s) and why their numbers suddenly increase. It's clear that human activities affect vole populations. We unintentionally make their living conditions better by growing their favorite foods or creating good places for them to live. So, the first idea explains how they colonized the Northern Plateau. But it doesn't explain the huge population booms or the regular ups and downs. These are natural cycles caused by internal factors (social behavior) and helped by external ones (food and predators).

How to Control Vole Plagues

To fight any pest, it's important to have as much information as possible about its causes and how it develops. These problems happen all the time, but the same solution doesn't always work. First, you need to know what's causing the damage, then act quickly. However, in Spain, there aren't enough up-to-date studies on voles. People have to use older information or learn from other countries. Also, much of the information online or in the news is often biased or not useful.

According to biologist Juan José Luque-Larena from the University of Valladolid:

"There is a complete lack of strictness, a lot of confusion, and no research. When bird flu appeared, everyone agreed research was needed, but anyone can talk about voles."

Preventing Plagues

A plague that is already very bad is impossible to get rid of completely. At best, you can control the numbers, stop some outbreaks, or reduce the damage. But to truly succeed, you need to prevent it. The first step is to count the number of harmful animals. Vole counts should be done in specific areas that are usually prone to plagues, using approved traps or by observing them.

Counting voles can be the best way to predict how their population will change. For the common vole, if counts in January show less than 50 voles per hectare, there's likely no danger. If the number is higher, especially if the winter is mild, action is needed to prevent a plague.

When food is scarce, using poison (always controlled by authorities) can be very effective. Voles don't have many other food choices, so they will eat the baits. This means poison works much better in winter.

Other good ways to prevent plagues include helping and protecting the voles' natural enemies (birds of prey, weasels, foxes, storks). Birds of prey should be protected by law, and special perches or nesting spots can be set up for them.

For small farms, using plants that voles don't like can help. For example, plants like Stramonium or belladonna are toxic to voles. Rue, squill, fritillaria, and castor bean also work similarly.

Pests are worse in areas where only one type of crop is grown, especially if it's the same crop year after year. So, changing and rotating crops helps control voles. Keeping fields clean and well-maintained is also good, but always respecting the variety of living things. Plowing empty fields deeply, removing weeds from farmlands, ditches, and around trees helps stop voles from spreading. Allowing cows to graze on leftover crop stalks is doubly effective: cattle crush many burrows and clean the ground. Destroying burrows with machines, creating areas without food (like bare land or plastic-covered areas), or using chemical repellents forces voles to gather where traps or poison are placed. In short, the richer the natural environment, the less likely it is to have pests. Good farming and environmental management is the best way to prevent disaster.

Trapping Voles

Catching voles can be very simple because they can't jump or climb well. A common way is to place small containers filled with water near where they feed. The voles fall in and drown. Metal boxes from a French association are also very effective.

However, trapping is mostly useless in large areas. It's only helpful for counting voles or in small, controlled places like parks, gardens, orchards, or swimming pools.

Burning Stover

In 2005, the Spanish government banned burning stover (leftover crop stalks) to prevent fires, following rules from the European Union. After the 2007 vole plague, many farming groups asked for permission to burn stover again to fight the voles. Even though it wasn't fully allowed, the regional government decided to try controlled burning in some specific places to see if it worked. They focused on irrigated areas or regions known for special farm products.

After a few weeks, it became clear that burning the straw didn't get hot enough to kill the voles. The heat only reached the top 10 centimeters of soil, so most voles could hide safely in their burrows.

Some farming groups, like ASAJA, COAG, UCCL, and UPA, supported by engineer Fernando Franco Jubete, believed that burning only a few areas was useless. They thought it needed to be widespread to work, forcing voles into special firebreak areas where chemicals could be used.

Even though burned areas scare voles away (because there's no food or shelter), burning is still bad for other animals and the environment. Any tiny living things in the top 10 cm of soil die, which stops them from helping the soil breathe and become fertile. Sulfur and carbon increase, while nitrogen disappears, meaning more fertilizers are needed to balance the soil. Small animals like reptiles, insects, hares, and birds are greatly affected and almost disappear from burned land. Also, voles simply leave the burned farms and move to other areas, which can spread the problem to less affected places.

Chemical Solutions

Anticoagulant poisons are often used to fight pests like voles. The regional government allowed and even gave out Chlorophacinone. This poison comes in different forms, like liquid, paste, or flavored blocks. The European Commission is still deciding whether to fully approve or ban Chlorophacinone, but for now, it's legal and approved in Spain.

There aren't many studies in Spain on how Chlorophacinone affects different animals. However, studies in the United States show that this poison is more harmful to small mammals than to birds or cattle. But this depends on how much they are exposed to it. Also, Chlorophacinone becomes less toxic when it gets wet. Still, there's a real risk to all kinds of animals, not just rodents. Some birds like bustards, larks, calandra larks, partridges, and ducks are especially sensitive. Among mammals, rabbits and hares were very vulnerable, with over 80% dying. For farm animals, Chlorophacinone was very harmful to lambs, and many died.

In March 2007, when the pest had spread widely in Tierra de Campos (Province of Palencia), the government decided to spread Chlorophacinone grains over 20,000 hectares of land. The poison wasn't used correctly and killed many pigeons, rabbits, larks, wild boars, and other wild or protected birds. Some environmental groups, including WWF/Adena, accused the government of a crime against public health. Most accusations were against the farming service in Palencia. Soon after, other groups like Global Nature Fund and Ecologistas en Acción also complained. The complaint went to the Public Prosecutor's Office, and the Nature Protection Service (SEPRONA) of the Civil Guard started investigating with help from the University of León. A SEPRONA report stated:

"We believe these animals are a risk to public health and should not be eaten by people until the widespread use of this rodenticide stops."

The agricultural engineer, Fernando Franco Jubete, also disagreed with this decision: "Chlorophacinone treatment should never have been approved, it was an ecological disaster that solved nothing... a broad-spectrum chemical product cannot be thrown away everywhere because it causes an ecological disaster."

The secretary general of a farmers' union in Palencia, Domiciano Pastor, explained that they had warned the government since September 2006, but the authorities took too long to respond. Regarding the accidental poisoning of other animals, he added, "There weren't so many deaths, but if the method isn't good, we don't want it to be used."

The End of the Plague

During the winter and early 2008, the vole population in Castile and León returned to normal levels. The regional government, as explained by Silvia Clemente, the Minister of Agriculture, spent about 24 million euros to stop the plague. However, it was later shown that despite the government's efforts, the poisons didn't really control the plague. Instead, the vole population went back to normal on its own. Much of this happened because of the weather, as the mayor of Fresno el Viejo, one of the most affected towns, admitted.

See also

In Spanish: Plaga de topillos en Castilla y León de 2007 para niños

In Spanish: Plaga de topillos en Castilla y León de 2007 para niños

- Integrated pest management

- Rotterdam Convention

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |