Long-toed salamander facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Long-toed salamander |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Ambystoma

|

| Species: |

macrodactylum

|

| Subspecies | |

|

A. m. columbianum |

|

|

|

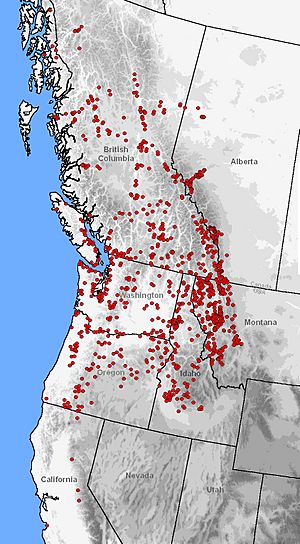

| Distribution of A. macrodactylum (red dots) in western North America | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) is a type of mole salamander. It belongs to the family Ambystomatidae. These salamanders are usually about 4 to 9 centimeters (1.6 to 3.5 inches) long when they are grown. They have a unique look with black, brown, and yellow spots. A special feature is their very long fourth toe on their back feet. Scientists believe this salamander and the blue-spotted salamander came from a common ancestor. This happened when a large ancient sea in North America dried up.

You can mostly find long-toed salamanders in the Pacific Northwest. They live from sea level up to 2,800 meters (9,200 feet) high in the mountains. They can live in many different places. These include rainforests, pine forests, and mountain areas near rivers. They also live in sagebrush plains and alpine meadows. During their breeding time, they live in slow streams, ponds, and lakes. In winter, they hibernate (sleep) to stay warm. They use energy stored in their skin and tail to survive.

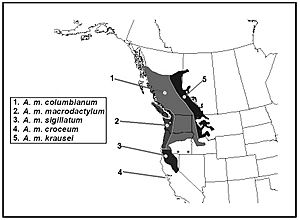

There are five different types, or subspecies, of long-toed salamanders. Each type has its own unique genes and looks. The IUCN says the long-toed salamander is of Least Concern. This means it's not currently in danger of disappearing. However, many human activities, like building and farming, can harm their homes.

Contents

What is a Long-Toed Salamander?

The long-toed salamander is part of the mole salamander family. This family started about 81 million years ago. They are also part of a group called Salamandroidea. This group includes all salamanders that can have internal fertilization. The closest relative to the long-toed salamander is the blue-spotted salamander. That salamander lives in eastern North America.

Appearance and Features

The long-toed salamander has a dark body, usually black. It has a stripe on its back that can be tan, yellow, or olive-green. This stripe might also look like a line of spots. The sides of its body can have small white or light blue spots. Its belly is dark brown or sooty with white flecks.

Eggs and Young Larvae

The eggs of this salamander look like those of the northwestern salamander and tiger salamander. Like many amphibians, their eggs are covered in a clear, jelly-like layer. This lets you see the embryo growing inside. Long-toed salamander eggs do not have green algae, unlike some other salamander eggs. The eggs are about 2 millimeters (0.08 inches) wide.

When they are very young, both in the egg and as new larvae, they have "balancers." These are thin skin parts that stick out from their heads. They help support the head. These balancers fall off later. Then, their outside gills grow bigger. After losing the balancers, their gills look sharp and flared. As they grow, their legs and toes appear, and their gills disappear. This change is called metamorphosis.

Larval Skin and Color

The skin of a larva has black, brown, and yellow spots. Their skin color changes as they grow. This happens because special color cells, called chromatophores, move around. There are three types of these cells: yellow (xanthophores), black (melanophores), and silvery (iridiophores). As the larvae get older, the black cells gather, making the background darker. The yellow cells line up along the spine and on top of the legs. The rest of the body gets silvery spots on the sides and underneath.

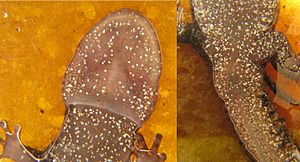

Adult Features

When larvae go through metamorphosis, they grow toes. A fully grown long-toed salamander has four toes on its front legs. It has five toes on its back legs. Its head is longer than it is wide. The long outer fourth toe on its back foot is what gives this salamander its name. The word macrodactylum comes from Greek words meaning "long" and "toe."

Adult salamanders have dark brown, dark gray, or black skin. They have a blotchy stripe of yellow, green, or dull red on their backs. Their sides have dots and spots. Underneath their legs, head, and body, they are white, pinkish, or brown. They have larger white spots and smaller yellow spots. Adults are usually about 4 to 8 centimeters (1.5 to 3 inches) long.

Where They Live

The long-toed salamander is very adaptable. It can live in many different places. These include temperate rainforests, coniferous forests, and mountain areas near rivers. They also live in sagebrush plains, red fir forests, and alpine meadows. You can find adults hiding under logs, rocks, or in small animal burrows in forests. During spring, when they breed, they can be found near the edges of rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds. They often visit temporary pools of water.

This salamander is one of the most widespread in North America. Only the tiger salamander lives in more places. They live from sea level up to 2,800 meters (9,200 feet) high. Their range stretches along the Pacific Coast from Monterey Bay and Santa Cruz, California all the way to Juneau, Alaska. From the Pacific coast, they spread east to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Montana and Alberta.

Life Cycle and Behavior

Eggs and Larvae

Like all amphibians, the long-toed salamander starts as an egg. In colder northern areas, eggs are laid in lumpy groups. They are attached to grass, sticks, rocks, or mud in calm ponds. A single group can have up to 110 eggs. Females put a lot of energy into making eggs. One female can lay up to 264 eggs. Each egg is about 0.5 millimeters (0.02 inches) wide. The eggs are held together by a jelly-like outer layer. In warmer southern areas, eggs are sometimes laid one by one. These egg masses add important nutrients to the water and nearby forests. They also provide a home for tiny water molds.

Larvae hatch from their eggs in two to six weeks. They are born carnivores, meaning they eat meat. They instinctively hunt small invertebrates that move. Their first foods include tiny water crustaceans and tadpoles. As they grow, they eat larger prey. Some larvae even grow bigger heads and become cannibals. They will eat other salamander larvae, even their own siblings, to survive.

Metamorphosis and Young Salamanders

After growing for at least one season (about four months on the Pacific coast), the larvae change. They absorb their gills and metamorphose into young salamanders that live on land. These young salamanders roam the forest floor. Metamorphosis can happen as early as July in low areas. In higher, colder places, larvae might stay in the water for an extra season before changing. They grow bigger before they leave the water.

Adult Life

As adults, long-toed salamanders are often hard to spot. They live mostly underground. They dig, move around, and eat invertebrates in forest soil, rotting logs, small rodent burrows, or rock cracks. Their diet includes insects, tadpoles, worms, beetles, and small fish.

Salamanders can be eaten by garter snakes, small mammals, birds, and fish. An adult salamander can live for 6 to 10 years. The largest ones can weigh about 7.5 grams (0.26 ounces). They can reach about 8 centimeters (3.1 inches) from snout to vent. Their total length, including the tail, can be up to 14 centimeters (5.5 inches).

Seasonal Behavior

The life cycle of the long-toed salamander changes a lot depending on how high up they live and the climate. They usually move to and from breeding ponds when it rains enough. Or when ice melts to fill the ponds. Eggs can be laid in southern Oregon as early as mid-February. In northern Washington, it can be from January to July. In Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta, it's from mid-April to early May.

Adults travel back to the ponds where they were born to breed. Males usually arrive earlier and stay longer than females. Sometimes, you can even see them moving along snow banks on warm spring days. Males look different from females only during the breeding season. Males have a larger, swollen area near their vent (where waste leaves the body).

Breeding Behavior

The time when salamanders breed depends on where they live. Salamanders in lower areas breed in fall, winter, and early spring. Those in higher, colder areas breed in spring and early summer. In high places, they might even enter ponds that still have ice.

Many adult salamanders gather together (more than 20) under rocks and logs near the water's edge. They breed very quickly over a few days. They like to breed in small ponds, marshes, shallow lakes, and other still waters that don't have fish.

Like other mole salamanders, they have a special courtship dance. They rub their bodies together and release special chemicals called pheromones from their chin. Then, the male puts down a "spermatophore." This is a gooey stalk with a packet of sperm on top. He then guides the female to pick up the sperm packet. Males can mate more than once. They might lay up to 15 spermatophores in a few hours.

The courtship dance is similar to other Ambystoma species. Males approach females and grab them from behind their front legs. This is called amplexus. They shake the female. The male rubs his chin on the female's head. The female might struggle at first, but then she calms down. If the female accepts, the male moves forward. He positions his tail over her head, waving the tip. The female follows him. When the male stops and lays a spermatophore, the female moves forward to receive the sperm packet. Females lay their eggs a few days after mating.

Energy and Defense

In some warmer areas, adult salamanders stay active all winter, except during very cold spells. But in colder northern areas, they hibernate during winter. They burrow deep underground, below the frost line. They often gather in groups of 8 to 14. While hibernating, they use energy stored in their skin and tail.

These stored proteins also help them defend themselves. When a long-toed salamander feels threatened, it waves its tail. It then releases a sticky, white, milky substance. This substance is bad-tasting and probably poisonous. Their skin color can also be a warning to predators that they taste bad. This is called aposematism. Their skin colors and patterns vary a lot. They can be dark black to reddish brown with spots or blotches of pale red-brown, pale green, or bright yellow. An adult salamander can also drop part of its tail to escape. This is called autotomy. The tail wiggles, distracting the predator, while the salamander slips away. The ability of their tail to regrow is very interesting to medical scientists.

Conservation Status

The IUCN says the long-toed salamander is of Least Concern. This means it is not in immediate danger. However, many human activities are harming their homes. This has led to new efforts to protect them. Protecting different groups of salamanders is important. This is because they help the environment in many ways. For example, salamanders play a key role in the soil, helping with nutrient cycling in wetlands and forests.

Amphibians like the long-toed salamander are often seen as signs of a healthy environment. This is because they live both in water and on land. Also, their skin is semi-permeable, meaning it can absorb water and oxygen. This means they might be more sensitive to pollution. However, scientists are still studying how much different amphibians are affected by pollution.

Long-toed salamander populations are threatened by habitat loss and division. This happens when their homes are broken up by roads or buildings. Introduced species, like fish put into lakes where they don't naturally belong, also threaten them. For example, introduced goldfish eat salamander eggs and larvae. Increased UV radiation from the sun is another threat. It can cause deformities and reduce their survival.

Forestry and road building can harm salamanders. Roads can make it hard for them to migrate. Places like Waterton Lakes National Park have built special tunnels under roads. These tunnels help salamanders cross safely. Salamanders are also negatively affected by logging if forests don't leave enough protected areas around wetlands where they breed. Some populations near the Peace River Valley have been lost because wetlands were cleared for farming.

The subspecies Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum, also known as the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander, is a special concern. It was protected in 1967 under the US Endangered Species Act. This subspecies lives in a small area in Santa Cruz County and Monterey County, California. Before it was protected, its few remaining populations were threatened by development. This subspecies is unique. It has special skin patterns, a unique tolerance for moisture, and lives only in this small area. Other subspecies include A. m. columbianum, A. m. krausei, A. m. macrodactylum, and A. m. sigillatum.

Subspecies of Long-Toed Salamanders

There are five different subspecies of long-toed salamanders. Scientists tell them apart by where they live and the patterns on their back stripe.

Scientists use DNA to study the different subspecies. This DNA analysis shows slightly different areas for each type. The way populations are spread out and their genetics are linked to the mountains and valleys of western North America. Long-toed salamanders tend to return to the same breeding ponds. This reduces how much they spread to new areas. This also means that different groups of salamanders become more genetically different from each other. Genetic differences are higher in long-toed salamanders than in most other vertebrate animals. Natural barriers like dry lowlands or very cold, high mountains (above 2,200 meters or 7,200 feet) limit their movement.

One study found another type of salamander that came from an area in the Salmon River Mountains, Idaho. About 10,000 years ago, after the last ice age, glaciers melted. This opened a path for these southern salamanders to move north. They now live in the same areas as A. m. krausei and moved north into the Peace River (Canada) Valley.

See also

In Spanish: Salamandra de dedos largos para niños

In Spanish: Salamandra de dedos largos para niños