Arab–Khazar wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Arab–Khazar wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Early Muslim conquests | |||||||

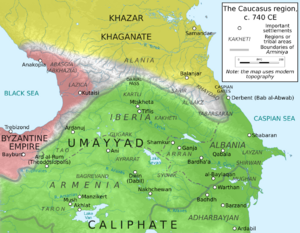

Map of the Caucasus region around 740 CE, after the Second Arab–Khazar War |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rashidun Caliphate (until 661) Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) Abbasid Caliphate (after 750) |

Khazar Khaganate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

The Arab–Khazar wars were a series of fights between the Khazar kingdom and different Arab caliphates. These wars happened in the Caucasus region from about 642 to 799 CE. Smaller local groups also joined in, helping either side.

Historians usually talk about two main periods of fighting: the First Arab–Khazar War (around 642–652) and the Second Arab–Khazar War (around 722–737). There were also smaller attacks and clashes from the mid-600s to the late 700s.

These wars started because the new Rashidun Caliphate wanted to control the South Caucasus (also called Transcaucasia) and the North Caucasus. The Khazars had already been in this area since the late 500s.

The first Arab attack began in 642. They captured Derbent, an important city that guarded the eastern mountain pass along the Caspian Sea. After some smaller attacks, a large Arab army was defeated in 652 near the Khazar town of Balanjar. This ended the first major period of fighting.

Big battles stopped for several decades. Only small raids happened, mostly by Khazars and North Caucasian Huns into the South Caucasus in the 660s and 680s.

The fighting between the Khazars and the Arabs (now under the Umayyad Caliphate) started again after 707. There were occasional raids across the Caucasus Mountains. After 721, the conflict grew into a full-scale war.

Arab generals like al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah and Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik led their armies. They took back Derbent and the southern Khazar capital of Balanjar. But these wins didn't stop the Khazars, who were nomadic. They kept launching big raids deep into the South Caucasus.

In 730, the Khazars launched a huge attack. They badly defeated the Umayyad forces at the Battle of Ardabil, where al-Jarrah was killed. The next year, the Arabs fought back, pushing the Khazars north. Maslama then got Derbent back. It became a major Arab military base.

In 732, Marwan ibn Muhammad (who later became a caliph) took over. For a while, the fighting was smaller. But in 737, Marwan led a massive army north to the Khazar capital, Atil, near the Volga River. After the Khazar ruler, the Khagan, agreed to surrender, the Arabs left.

The 737 campaign marked the end of large-scale wars. Derbent became the northernmost point of the Muslim world. The Muslims controlled the South Caucasus, but the North Caucasus stayed in Khazar hands. The long wars also weakened the Umayyad army. This helped lead to the fall of the Umayyad dynasty in 750, replaced by the Abbasid Caliphate.

After this, relations between Muslims in the Caucasus and the Khazars were mostly peaceful. The Caucasus became a trade route linking the Middle East to Eastern Europe. Peace was broken by two Khazar raids in the 760s and in 799. These raids happened because attempts to arrange marriages between Arab leaders and the Khazar Khagan failed. Smaller fights continued until the Khazar state collapsed in the late 900s. But these later conflicts were never as big as the wars in the 700s.

Contents

Why They Fought: The Caucasus as a Borderland

The Arab–Khazar wars were part of a long history of fights. These fights were between nomadic people from the Pontic–Caspian steppe (large grasslands) and settled people south of the Caucasus mountains.

Two main routes cross these mountains: the Darial Pass in the middle and the Pass of Derbent in the east, along the Caspian Sea. These routes have been used for invasions since ancient times. So, protecting the Caucasus border from attacks by groups like the Scythians and the Huns was very important for empires in the Near East.

People in ancient and medieval Middle Eastern cultures believed that Alexander the Great had built a wall in the Caucasus. This wall was supposed to keep out mythical hordes called Gog and Magog. These were seen as "northern barbarians." If Alexander's wall failed and Gog and Magog broke through, it was believed the world would end.

Starting with Peroz I (ruled 457–484), the rulers of the Sasanian Empire (an ancient Persian empire) built a line of stone forts. These forts protected their border on the Caspian shore. When finished by Khosrow I (ruled 531–579), this wall stretched over 45 kilometers (28 miles). The fortress of Derbent was the most important part of this defense. Its Persian name, Dar-band, means "Knot of the Gates."

The Turkic Khazars arrived in the area of modern-day Dagestan in the late 500s. At first, they were part of the First Turkic Khaganate. After that kingdom fell apart, the Khazars became an independent and powerful group in the northern Caucasus by the 600s. Because they were the newest powerful group from the steppes, some writers in the Middle Ages thought the Khazars were Gog and Magog. They also thought the Sasanian forts at Derbent were Alexander's wall.

Modern historians believe the Khazars first fought in the South Caucasus during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. They were allies of the Byzantine Empire. The Turks attacked Derbent in 627 and joined the Byzantines in attacking Tiflis. Their help was key to the Byzantine victory. For a short time, the Turks controlled parts of the South Caucasus. But after their leader was killed around 630, their control ended. The Khazars then became independent and grew powerful between the 660s and 680s. They defeated another group called Old Great Bulgaria and expanded into the North Caucasus.

Who Fought: The Armies

In the Caucasus, the Khazars met the new Arab caliphate. The Arabs had taken control of the South Caucasus in the 640s during their first wave of early Muslim conquests. The eastern Caucasus became the main battleground. Arab armies wanted to control Derbent (which they called 'Gate of Gates') and the Khazar cities of Balanjar and Samandar. We don't know exactly where these Khazar cities were, but Arab writers called them Khazar capitals. The Khazars later moved their capital further north to Atil to avoid Arab attacks.

The Arab Armies

Like other people in the Near East, the Arabs knew the legend of Gog and Magog. These figures appear in the Quran as Yaʾjuj wa-Maʾjuj. After the Muslim conquests, Arab ideas about the Caucasus changed. They saw it as part of a huge mountain chain that divided civilized lands from a 'Land of Darkness' to the north. This idea came from Persian and possibly ancient Babylonian beliefs.

So, the caliphs (Muslim rulers) soon felt it was their duty to "protect the civilized world from the northern barbarians." This idea was strengthened by the Muslim way of dividing the world. They had the House of Islam (lands ruled by Muslims) and the House of War (lands not ruled by Muslims). The Khazars, who followed their own pagan beliefs, were in the House of War.

While the Byzantines and Sasanians tried to keep the steppe peoples out with forts and alliances, the Arab caliphs wanted to conquer new lands. Their push north threatened the Khazars' independence. Historians say the Muslim caliphate was very focused on its beliefs. It was dedicated to `jihad`, which meant working to establish God's rule on Earth through constant military effort against non-Muslims.

The early Muslim state was set up for expansion. All healthy adult Muslim men could be called to fight. This gave them a huge number of potential soldiers. One historian estimates that around 700 CE, 250,000 to 300,000 men were listed as potential soldiers. This force was spread across the empire. Many soldiers didn't want to fight if there wasn't a good chance of easy victory and loot. But Arab volunteers could also join. This gave the Arabs a clear advantage over their enemies. For example, the Byzantine army at the time had about 120,000 men, though some historians say it was as low as 30,000.

Arab armies had many light and heavy cavalry units. But they mainly relied on their infantry (foot soldiers). Arab cavalry often fought at the start of a battle, then got off their horses to fight on foot. Arab armies would dig trenches and form a wall of spears to stop cavalry charges. This shows how disciplined the Arab armies were, especially the elite Syrian troops. These troops served all the time, not just for specific campaigns. They were a professional, standing army. Their better training and discipline helped them against nomadic groups like the Khazars.

In the 700s, Arab armies often had local forces with them. These forces came from local rulers who were under Arab control. These local rulers had often suffered from Khazar raids themselves. For example, in 732, the prince of Armenia agreed to provide Armenian cavalry to the Arab army for three years.

The Khazar Armies

The Khazars used a strategy common for nomadic groups. Their raids went deep into the South Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia. But these raids were not meant for conquest. Instead, they were a way to test their neighbors' defenses and gather loot. Getting and sharing loot was very important for their tribal groups. For the Khazars, controlling the Caucasus passes was a key goal.

We don't have many details about how Khazar armies were put together or how they fought. The names of Khazar commanders are rarely written down. Even though the Khazars adopted some things from the settled civilizations to their south and had towns, they remained a tribal, semi-nomadic power. Like other steppe societies from Central Asia, they fought in a mobile way, relying on skilled, tough cavalry. Medieval writings often mention the fast movements and sudden attacks of Khazar cavalry. In the few detailed battle descriptions, Khazar cavalry always started the attacks. We don't have records of heavy cavalry, but archaeological finds show they used heavy armor for riders and possibly for horses. We can assume they had infantry (foot soldiers), especially for sieges, even if it's not directly mentioned.

Modern historians say that the Khazars used advanced siege machines. This shows that their military skills were as good as other armies at the time. The less strict organization of the semi-nomadic Khazar state also helped them against the Arabs. They didn't have one main administrative center. If they lost a city, it wouldn't stop their government or force them to surrender.

The Khazar army was made up of Khazar troops and soldiers from their vassal princes and allies. We don't know the total size of their army. Reports of 300,000 men in the 730 invasion are clearly too high. One historian notes that the Khazars "never entered into battle without having a numerical advantage" over the Arabs. This often forced the Arabs to retreat. This suggests the Khazars were good at planning and gathering information about their enemies.

How the Wars Connected to Other Conflicts

The Arab–Khazar wars were also linked to the long struggle between the Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine emperors had close ties with the Khazars, forming an alliance for most of this period. For example, Emperor Justinian II married the Khazar princess Theodora of Khazaria in 705.

The possibility of the Khazars joining with the Byzantines through Armenia was a big threat to the Caliphate. Armenia was close to the Umayyad heartland in Syria. But this didn't happen. Armenia was mostly peaceful, with the Umayyads giving it a lot of freedom. The Byzantines also didn't actively campaign there. Because of the shared threat of Khazar raids, the Umayyads found the Armenians (and their neighbors, the Georgians) willing to help against the Khazars.

Some historians thought the Arabs wanted to attack the Byzantine Empire from the north. But more recent scholars disagree. They say this plan was too ambitious and that the Arabs didn't have enough detailed maps at the time. It's more likely that the Arabs' push north beyond the Caucasus was just part of their general expansion. Local Arab commanders often took opportunities without a big plan, sometimes even against orders from the caliph.

From a strategic point of view, it's more likely that the Byzantines encouraged the Khazars to attack the Caliphate. This would take pressure off their eastern border in the early 700s. Byzantium benefited from Muslim armies being sent north in the 720s and 730s. The Byzantine–Khazar alliance led to another marriage in 733, between future emperor Constantine V and Khazar princess Tzitzak.

Another idea is that the Caliphate wanted to control the northern part of the Silk Road. But this is also debated. Warfare actually decreased when the Silk Road trade grew, after the mid-700s.

The First War and What Happened After

Early Arab Attacks

The Khazars and Arabs first clashed as the Muslims expanded their empire. By 640, after conquering Byzantine Syria and Upper Mesopotamia, the Arabs reached Armenia. Arab and Armenian writings differ on the details, but by 655, Armenian princes had surrendered. Both the Byzantine and Persian parts of Armenia were under Arab control.

Arab rule was briefly overthrown during the First Muslim Civil War (656–661). But after the war, Armenian princes again paid tribute to the new Umayyad Caliphate. The Principality of Iberia made a similar agreement. Only Lazica (on the Black Sea coast) remained under Byzantine influence. Neighboring Adharbayjan was conquered between 639 and 643. Raids into Arran (Caucasian Albania) in the early 640s led to its cities surrendering. Like in Armenia, Arab rule wasn't fully set up until after the First Muslim Civil War.

Arab historians say the first attack on Derbent happened in 642. Abd al-Rahman ibn Rabi'a led the advance. One historian, Al-Tabari, wrote that the Persian governor of Derbent offered to surrender the fortress to the Arabs. He would help them against the Caucasian people if he and his followers didn't have to pay the `jizya` (a tax on non-Muslims). Caliph Umar (ruled 634–644) agreed.

Al-Tabari also says the first Arab push into Khazar lands happened after Derbent was captured. Abd al-Rahman ibn Rabi'a reached Balanjar without losing any men. His cavalry went as far as 800 kilometers (500 miles) north, to al-Bayda on the Volga, the future Khazar capital. Modern scholars question this date and the claim of no Arab losses. From Derbent, Abd al-Rahman launched frequent small raids against the Khazars and local tribes in the following years.

Abd al-Rahman, or his brother Salman, led a large army north in 652. They ignored the caliph's orders to be careful. Their goal was to take Balanjar. The town was attacked for several days. Both sides used catapults. Then, a Khazar relief force arrived, and the people inside the city attacked. This led to a major defeat for the Arabs. Abd al-Rahman and 4,000 of his troops were killed. The rest fled to Derbent or Gilan in northern Iran.

Khazar and Hunnic Raids into the South Caucasus

The Arabs didn't attack the Khazars again until the early 700s. This was because of the First Muslim Civil War and other important conflicts. Even though Arab rule was re-established, the South Caucasus principalities were not fully under Arab control. Their resistance, encouraged by Byzantium, was hard to overcome. For decades after the first Arab conquest, local rulers had a lot of freedom. Arab governors worked with them, and they had their own small armies.

The Khazars avoided large-scale attacks in the south. The last Sasanian shah, Yazdegerd III, asked for their help but got no answer. After the Arab attacks, the Khazars left Balanjar. They moved their capital further north to try and avoid the Arab armies. However, Khazar helpers and troops from other groups fought alongside the Byzantines against the Arabs in 655.

The only recorded fights in the late 600s were a few Khazar raids into the South Caucasus. These areas were loosely under Muslim control. These raids were mainly for plunder, not for conquest. In one raid into Albania in 661–662, the Khazars were defeated by the local prince, Juansher.

A large raid across the South Caucasus in 683 or 685 was more successful. This was also a time of civil war in the Muslim world. The Khazars took much loot and many prisoners. They killed the ruling princes of Iberia and Armenia. At the same time, the North Caucasian Huns also attacked Albania in 664 and 680. In the first attack, Prince Juansher had to marry the Hunnic king's daughter. Historians debate if the Huns acted alone or for the Khazars. Some think the Hunnic ruler was a Khazar vassal. If so, Albania was indirectly ruled by the Khazars in the 680s.

The Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I (ruled 661–680) tried to counter Khazar influence. He invited Juansher to Damascus twice. The 683/685 Khazar raid might have been a reaction to these invitations. Another historian, Thomas S. Noonan, says the Khazars were careful. They avoided direct fights with the Umayyads and only attacked during civil wars. Noonan believes this caution was because the Khazars were busy strengthening their rule in the Pontic–Caspian steppe. They were happy with just bringing Albania into their sphere of influence.

The Second War

Relations between the two powers were quiet until the early 700s. Then, a new and more intense period of conflict began. Around 700, Byzantine power in the Caucasus was weak. The civil war in the Caliphate ended in 693. The Umayyads defeated the Byzantines, who then went through a long period of trouble.

The Arabs began a strong attack against Byzantium. This led to a big attack on the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, in 717–718. At the same time, the Caliphate tightened its control over the Christian areas of Transcaucasia. After a large Armenian rebellion was put down in 705, Armenia, Iberia, and Albania came under direct Arab rule as the province of Arminiya. Only western South Caucasus (modern-day Georgia) remained free from direct control by either side. The two powers now faced each other for control of the Caucasus.

The first Arab advance happened as early as 692/693. An army was sent to secure the pass of Derbent. But the Arab forces soon had to retreat. The conflict started again in 707. Umayyad general Maslama, a son of Caliph Abd al-Malik, led a campaign in Adharbayjan and up to Derbent. Other attacks on Derbent are reported in 708 and 709. But the most likely time for the Arabs to take Derbent back is Maslama's expedition in 713/714.

The Armenian historian Łewond wrote that Derbent was held by the Huns at that time. Another chronicle says 3,000 Khazars defended it. Maslama captured it only after someone showed him a secret underground passage. Łewond also says the Arabs destroyed the walls because they couldn't hold the fortress. Maslama then went deeper into Khazar land, trying to control the North Caucasian Huns (who were Khazar vassals). The Khazar Khagan (ruler) met the Arabs at Tarku. But the two armies didn't fight for several days, except for some single duels. The arrival of Khazar reinforcements forced Maslama to quickly leave his campaign and retreat. He left his camp and equipment behind as a trick.

In response, in 709 or around 715, the Khazars invaded Albania with an army said to be 80,000 strong. In 717, the Khazars raided Adharbayjan in force. Most of the Umayyad army was busy with the siege of Constantinople. Caliph Umar II (ruled 717–720) reportedly could only send 4,000 men to face 20,000 invaders. But the Arab commander Hatim ibn al-Nu'man still defeated and pushed back the Khazars. Hatim returned to the caliph with fifty Khazar prisoners. This was the first time such an event was recorded.

The Conflict Grows

In 721/722, the main part of the war began. Thirty thousand Khazars invaded Armenia that winter. They badly defeated the Syrian army of the local governor in February and March 722.

Caliph Yazid II (ruled 720–724) sent al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah, one of his best generals, north with 25,000 Syrian troops. The Khazars retreated to the Derbent area when they heard he was coming. Al-Jarrah learned that the local Lezgin chief was talking with the Khazars. So, al-Jarrah set up camp and said his army would stay there for days. Instead, he marched all night to Derbent and entered it without a fight.

From Derbent, al-Jarrah sent raiding groups into Khazar territory. His main army then met a Khazar army north of Derbent. The Khazars, led by Barjik (one of the Khazar Khagan's sons), reportedly had 40,000 men. The Arabs won, losing 4,000 men to the Khazars' 7,000. The Arab army moved north, capturing Khamzin and Targhu.

Finally, the Arab army reached Balanjar. The city had been strongly fortified in the mid-600s, but its defenses had been neglected. The Khazars defended their capital by surrounding the citadel with a "wagon fort" of 300 wagons tied together. This was a common tactic for nomadic groups. The Arabs broke through and stormed the city on August 21, 722. Most of Balanjar's people were killed or enslaved. A few, including its governor, fled north. The Arabs took so much loot that each of the 30,000 horsemen (likely an exaggeration) reportedly got 300 gold coins. Al-Jarrah is said to have paid to free the wife and children of Balanjar's governor. Muslim sources also say the governor offered to help the Arabs if he could get his belongings back.

Al-Jarrah's army also took nearby forts and continued north. The strong fortress city of Wabandar, with 40,000 households, surrendered in exchange for tribute. Al-Jarrah wanted to go to Samandar, the next big Khazar settlement. But he stopped his campaign when he learned the Khazars were gathering large forces there. The Arabs had not yet defeated the main Khazar army, which, like all nomad forces, didn't rely on cities for supplies. This force near Samandar and reports of rebellions behind them forced the Arabs to retreat south of the Caucasus. When he returned, al-Jarrah asked the caliph for more troops to defeat the Khazars. This shows how tough the fighting was. The caliph sent good wishes, but no more troops.

In 723, al-Jarrah reportedly led another campaign into Alania through the Darial Pass. Sources say he went "beyond Balanjar," conquering several forts and taking much loot. But there are few details. Modern scholars think this might be a confused account of the 722 Balanjar campaign. The Khazars raided south of the Caucasus in response. But in February 724, al-Jarrah decisively defeated them in a battle lasting several days. The new caliph, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (ruled 724–743), promised to send more troops but didn't. In 724, al-Jarrah captured Tiflis. This brought Caucasian Iberia and the lands of the Alans under Muslim control. These campaigns made al-Jarrah the first Muslim commander to cross the Darial Pass. This protected the Muslim side from Khazar attacks through the pass and gave the Arabs a second way to invade Khazar territory. Al-Jarrah was also the first Arab commander to settle Khazar prisoners as colonists.

In 725, the caliph replaced al-Jarrah with his half-brother Maslama. Maslama's appointment shows how important the caliph thought the Khazar front was. Maslama was a member of the ruling family and one of the empire's best generals. But Maslama stayed in another region, focusing on fighting the Byzantines. Instead, he sent al-Harith ibn Amr al-Ta'i to the Caucasus front. Al-Harith spent his first year making Muslim rule stronger in Caucasian Albania. The next year, Barjik launched a major invasion of Albania and Adharbayjan. The Khazars attacked Warthan with siege machines. Al-Harith defeated them, but the Arab position was clearly in danger.

Maslama took personal command of the Khazar front in 727. He faced the Khazar Khagan himself, as both sides increased their efforts. Maslama attacked, probably with more troops. He took back the Darial Pass and pushed into Khazar territory. He campaigned there until winter forced him to return. His second invasion the next year was less successful. Arab sources say the Umayyad troops fought for thirty or forty days in mud and rain before defeating the Khagan. But Maslama was ambushed on his way back. The Arabs left their baggage and fled through the Darial Pass to safety. After this, Maslama was replaced by al-Jarrah again. Maslama's campaigns didn't get the results he wanted. By 729, the Arabs had lost control of the northeastern South Caucasus and were defending again.

The Battle of Ardabil and Arab Response

In 729/730, al-Jarrah attacked again through Tiflis and the Darial Pass. One historian says he reached the Khazar capital, al-Bayda, but no other source agrees. Modern historians think this is unlikely. Al-Jarrah's attacks were followed by a massive Khazar invasion (reportedly 300,000 men). This forced the Arabs to retreat south of the Caucasus again and defend Albania.

It's unclear if the Khazar invasion came through the Darial Pass, the Caspian Gates, or both. Different commanders are mentioned for the Khazar forces. Arab sources say the invasion was led by Barjik (the Khagan's son). Al-Jarrah apparently spread out some of his forces. He moved his main army to Bardha'a and then to Ardabil. Ardabil was the capital of Adharbayjan. Most Muslim settlers and their families (about 30,000) lived inside its walls. The Khazars attacked Warthan. Al-Jarrah rushed to help the town. He then faced the main Khazar army at Ardabil.

After a three-day battle from December 7 to 9, 730, al-Jarrah's 25,000-man army was almost completely destroyed by the Khazars. Al-Jarrah was killed. Command went to his brother, who couldn't stop Ardabil from being looted. One historian says the Khazars took as many as 40,000 prisoners from the city, al-Jarrah's army, and the surrounding area. The Khazars raided the province freely, sacking Ganza and attacking other places. Some groups reached Mosul in the northern Jazira, close to the Umayyad heartland in Syria.

The defeat at Ardabil was a shock to the Muslims. It was the first time an enemy army had gone so deep into the Caliphate. Caliph Hisham again appointed Maslama to fight the Khazars. Until Maslama could gather enough forces, a skilled military leader named Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi was sent to stop the Khazar invasion. Sa'id went to Raqqa with a special spear and money to recruit men.

The forces he could gather right away were small. But he went to meet the Khazars, possibly ignoring orders to stay on defense. Sa'id met refugees from Ardabil along the way and enlisted them, paying each recruit ten gold coins.

Sa'id was lucky. The Khazars had spread out in small groups after their victory at Ardabil, plundering the countryside. The Arabs defeated them one by one. Sa'id took back Akhlat on Lake Van. Then he moved northeast to Bardha'a and south to help the siege of Warthan. He met a 10,000-strong Khazar army and defeated it in a surprise night attack. Most of the Khazars were killed. He rescued 5,000 Muslim prisoners, including al-Jarrah's daughter. The surviving Khazars fled north, with Sa'id chasing them. Muslim sources record other attacks by Sa'id on very large Khazar armies. In one, Barjik was reportedly killed in a single fight with the Arab general. These stories are probably more like exciting tales than exact history.

Sa'id's unexpected success angered Maslama. Sa'id was removed from command in early 731 by Maslama and put in prison. He was accused of putting the army in danger by disobeying orders. He was released and rewarded only after the caliph stepped in. Historians note that the jealousy between Arab commanders and their frequent changes hurt their war effort. It stopped them from developing a long-term plan to deal with the Khazar problem.

Protecting Derbent

Maslama took command of a large army and immediately attacked. He brought the provinces of Albania back under Muslim control. He reached Derbent, where he found a Khazar garrison of 1,000 men and their families. Leaving al-Harith ibn Amr al-Ta'i at Derbent, Maslama went north. He apparently took Khamzin, Balanjar, and Samandar. But he was forced to retreat after facing the main Khazar army.

The Arabs left their campfires burning and retreated in the middle of the night. They quickly reached Derbent. The Khazars followed Maslama's march south and attacked him near Derbent. But the Arab army fought back until a small, elite force attacked the Khagan's tent and wounded him. The Muslims, encouraged, then defeated the Khazars. The Khazar commander Barjik may have been killed in this battle.

Maslama used his victory to poison Derbent's water supply to drive out the Khazar soldiers. He made the city an Arab military colony. He rebuilt its forts and placed 24,000 troops there, mostly from Syria. Leaving his relative Marwan ibn Muhammad (who later became the last Umayyad caliph) in charge at Derbent, Maslama returned south for the winter. The Khazars went back to their abandoned towns. Maslama's results were not good enough for Caliph Hisham. He replaced his brother in March 732 with Marwan ibn Muhammad.

That summer, Marwan led 40,000 men north into Khazar lands. Accounts of this campaign are confusing. One source says he reached Balanjar and returned with much captured livestock. But the campaign also had heavy rain and mud. This sounds a lot like descriptions of Maslama's earlier trips. Another source says Marwan led a much smaller campaign just north of Derbent. Marwan was more active in the south. He made Ashot III Bagratuni the ruling prince of Armenia. This gave Armenia a lot of freedom in exchange for its soldiers serving in the Caliphate's armies. This special deal shows the Caliphate was having trouble finding enough soldiers. Around this time, the Khazars and Byzantines became closer. They made their alliance formal with the marriage of Constantine V to the Khazar princess Tzitzak.

Marwan's Invasion of Khazaria and the End of the War

After Marwan's 732 trip, a quiet period began. Sa'id al-Harashi replaced Marwan as governor in 733. But he didn't launch any campaigns for two years. This inactivity was likely because the Arab armies were tired. Marwan reportedly criticized the policy in the Caucasus to Caliph Hisham. He suggested he be sent to deal with the Khazars with a huge army of 120,000 men. When Sa'id asked to be relieved due to poor eyesight, Hisham appointed Marwan to replace him.

Marwan returned to the Caucasus around 735. He wanted to strike a decisive blow against the Khazars. But he could only launch local attacks for some time. He set up a new base and his first attacks were against smaller local rulers. Some historians say the Arabs and Khazars made peace during this time. Muslim sources either ignore this or say it was a trick by Marwan to gain time and mislead the Khazars.

Meanwhile, Marwan secured his rear. In 735, he captured three forts in Alania (near the Darial Pass). The Arabs also captured Tuman Shah, a local ruler, who was then put back in charge as an Arab client. Marwan campaigned the next year against another local prince. His castle was sacked, and its defenders killed even after they surrendered. Marwan also brought the Armenian groups who were against the Arabs under control. He then pushed into Iberia. Its ruler fled to the fortress of Anakopia on the Black Sea coast. Marwan attacked Anakopia, but had to leave because his army got sick. His harshness during the invasion of Iberia earned him the nickname "the Deaf" from the Iberians.

Marwan planned a massive campaign for 737 to end the war. He reportedly went to Damascus to ask Hisham for support. One historian says his army had 150,000 men. This included regular troops, volunteers, Armenian soldiers, and servants. Whatever its size, it was the largest army ever sent against the Khazars. He attacked from two directions at once. Thirty thousand men went north along the Caspian coast. Marwan crossed the Darial Pass with the main part of his forces.

The invasion met little resistance. Arab sources say Marwan held the Khazar envoy (messenger) and only released him with a declaration of war when he was deep in Khazar territory. The two Arab armies met at Samandar. Marwan then advanced to the Khazar capital of al-Bayda on the Volga. The Khagan retreated towards the Ural Mountains, but left a large force to protect the capital. This was a very deep push into enemy land. But it wasn't very important strategically. Travelers from the 900s described the Khazar capital as little more than a large camp.

The rest of the campaign is only told by one historian and others who used his work. According to this story, Marwan ignored al-Bayda and chased the Khagan north along the west bank of the Volga. The Khazar army followed from the east bank. The Arabs attacked the Burtas, who were Khazar subjects. They captured 20,000 families (or 40,000 people). The Khazars avoided battle. Marwan sent 40,000 troops across the Volga. The Khazars were surprised in a swamp. Ten thousand Khazars were killed, and 7,000 were captured.

This seems to have been the only major fight between the Arabs and Khazars in this campaign. The Khazar Khagan soon asked for peace. Marwan reportedly offered "Islam or the sword" (convert to Islam or fight). The Khagan agreed to convert to Islam. Two religious experts were sent to teach him about Islamic rules, like not drinking wine or eating pork. Marwan also brought many Slav and Khazar captives south. He resettled them in the eastern Caucasus. Some Slavs were settled in Kakheti, and Khazars in al-Lakz, where they became Muslim. The Slavs soon killed their governor and fled north. Marwan chased and stopped them.

Marwan's 737 expedition was the peak of the Arab–Khazar wars. But its results were small. The Arab campaigns after Ardabil may have stopped the Khazars from fighting more. But the Khagan's agreement to Islam or Arab rule was likely only because Arab troops were deep in his land. This couldn't last. The Arab armies left, followed by Muslim civil wars in the 740s. The Umayyad rule then collapsed. This "left little political pressure to remain Muslim." Even the Khagan's conversion to Islam is questioned by modern scholars. It seems more likely that a minor lord converted to Islam.

The Khagan's conversion is also contradicted because the Khazar court later adopted Judaism. This happened gradually. It was definitely happening by the late 700s. Many scholars believe the Khazar leaders converted to Judaism to show they were different from the Christian Byzantine and Muslim Arab empires. This was a direct result of the 737 events.

What Happened After and the Impact

Whatever truly happened in Marwan's campaigns, fighting between the Khazars and Arabs stopped for more than two decades after 737. Arab military activity continued until 741. Marwan launched repeated expeditions against smaller groups in modern-day Dagestan. These campaigns were more like raids to get loot and tribute to support the Arab army, rather than attempts to conquer permanently.

Despite the Umayyads setting up a stable border at Derbent, they couldn't go any further north. The Khazars resisted strongly. Historians compare the Umayyad–Khazar fight in the Caucasus to the Umayyads' fight with the Franks in the west, which ended at the Battle of Tours. Like the Franks, the Khazars played a key role in stopping the early Muslim conquest.

During the long conflict, the Arabs kept control over much of Transcaucasia. Khazar raids happened, but they never truly threatened Arab control. However, by failing to push the border north of Derbent, the Arabs had reached the limits of their expansion.

Arab control in most of their lands was weak. It was mostly through local princes who had submitted to Muslim rule. This submission was often just in name, unless Arab governors could enforce it by force. Also, people slowly converted to Islam, and it was likely not very deep at first. For about four centuries, the Khazars remained a barrier to Islam expanding further north.

The city of Balanjar is not mentioned after the Arab–Khazar wars. But a group called "Baranjar" was later recorded living in Volga Bulgaria. They were probably descendants of the original tribe from Balanjar who moved there because of the wars. Some historians believe the rise of the Saltovo-Mayaki culture in the steppe region was a result of the Arab–Khazar conflict. This is because Alans from the North Caucasus were resettled there by the Khazars.

Later Conflicts

The Khazars started raiding Muslim territory again after the Abbasid dynasty took over in 750. They went deep into the South Caucasus. By the 800s, the Khazars had regained control of Dagestan almost to Derbent. But they never seriously tried to challenge Muslim control of the southern Caucasus. At the same time, the new Abbasid dynasty's control over its empire was too weak for them to start big attacks like the Umayyads did.

Historians say the "Khazar-Arab Wars ended in a stalemate." This was followed by a gradual coming together that encouraged trade between the two empires. Large amounts of Arab coins found in Eastern Europe suggest that the late 700s marked the start of trade routes. These routes linked the Baltic Sea and Eastern Europe with the Caucasus and the Middle East.

The first conflict between the Khazars and the Abbasids happened because of a diplomatic move by Caliph al-Mansur (ruled 754–775). He wanted to strengthen ties with the Khazars. So, he ordered the governor of Armenia, Yazid al-Sulami, to marry a daughter of the Khagan Baghatur around 760. The marriage happened, but she and her child died during childbirth two years later. The Khagan suspected the Muslims of poisoning his daughter. So, he raided south of the Caucasus from 762 to 764.

Led by the Khwarezmian `tarkhan` Ras, the Khazars destroyed Albania, Armenia, and Iberia. They captured Tiflis. Yazid escaped capture. The Khazars returned north with thousands of captives and much loot. When the deposed Iberian ruler Nerse tried to get the Khazars to fight the Abbasids in 780, the Khagan refused. This was probably because the Khazars had a brief anti-Byzantine policy due to problems in the Crimea. At this time, the Khazars helped Leon II of Abkhazia break free from Byzantine rule.

Peace lasted between the Arabs and Khazars in the Caucasus until 799. This was the last major Khazar attack into the South Caucasus. Historians again say the attack was due to a failed marriage alliance. Georgian sources say the Khagan wanted to marry Shushan, the beautiful daughter of Prince Archil of Kakheti. He sent his general Bulchan to invade Iberia and capture her. Most of central K'art'li was taken. Prince Juansher was captured for several years. Shushan chose to take her own life rather than be captured. The furious Khagan had Bulchan executed.

Arab historians say the conflict was due to plans by the Abbasid governor to marry one of the Khagan's daughters. She died on the journey south. A completely different story is told by another historian. He says the Khazars were invited to attack by a local Arab leader. This was in revenge for the execution of his father, the governor of Derbent. According to Arab sources, the Khazars raided as far as the Araxes River.

Arabs and Khazars continued to clash occasionally in the North Caucasus during the 800s and 900s. But the fighting was local and much less intense than the wars in the 700s. One historian records a period of fighting from around 901 to 912. This might be linked to the Caspian raids of the Rus' (whom the Khazars allowed to cross their lands). For the Khazars, peace on their southern border became more important as new threats appeared in the steppes.

The Caliphate's power also decreased over the 800s and 900s. This allowed local Christian states to become independent. The final breakup of the Abbasid empire in the early 900s also led to the creation of large Muslim kingdoms in the region. The Khazar presence also lessened as their power collapsed in the 900s. They suffered defeats by the Rus' and other Turkic nomads. The Khazar kingdom shrank to its core around the lower Volga. This was far from the Muslim kingdoms of the Caucasus. The last Khazars found safety among their former enemies. One historian records that in 1064, "the remnants of the Khazars, consisting of three thousand households, arrived in Qahtan [somewhere in Dagestan] from the Khazar territory. They rebuilt it and settled in it."