Arthur Eddington facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Arthur Eddington

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Arthur Stanley Eddington

28 December 1882 Kendal, Westmorland, England

|

| Died | 22 November 1944 (aged 61) Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England

|

| Alma mater | University of Manchester Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Arrow of time Eddington approximation Eddington experiment Eddington's affine geometry Eddington limit Eddington number Eddington valve Eddington–Dirac number Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates Eddington stellar model Eddington–Sweet circulation |

| Awards | Royal Society Royal Medal (1928) Smith's Prize (1907) RAS Gold Medal (1924) Henry Draper Medal (1924) Bruce Medal (1924) Knight Bachelor (1930) Order of Merit (1938) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astrophysics |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Academic advisors |

|

| Doctoral students | Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Leslie Comrie Hermann Bondi |

| Other notable students | Georges Lemaître |

| Influences | Horace Lamb Arthur Schuster John William Graham |

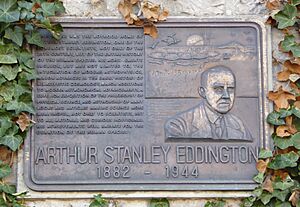

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was a famous English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He also thought deeply about the philosophy of science and helped explain science to everyone. The Eddington limit, which describes the brightest a star can shine, is named after him.

Around 1920, he was the first to guess how stars get their energy. He suggested it was from nuclear fusion, where light atoms combine to make heavier ones. This was a big mystery at the time!

Eddington also helped introduce Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity to the English-speaking world. Many scientific connections were cut during World War I. So, new ideas from German scientists were not well known in England. He even led an expedition to observe a solar eclipse in 1919. This trip helped prove Einstein's theory was right. He became famous for explaining this complex theory in a way that people could understand.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Arthur Eddington was born on December 28, 1882, in Kendal, England. His parents were Quakers. His father was a school headmaster.

Sadly, his father died in 1884 from typhoid. His mother then raised Arthur and his sister with little money. They moved to Weston-super-Mare. Arthur was first taught at home, then went to a preparatory school. There is a special plaque on their old house to remember him.

In 1893, Arthur went to Brynmelyn School. He was a very smart student, especially in math and English. He won a scholarship to Owens College, Manchester, in 1898. This college later became the University of Manchester. He studied physics there for three years. His teachers, Arthur Schuster and Horace Lamb, greatly influenced him. He graduated with top honors in physics in 1902.

Because of his excellent work, he won another scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1902. In 1904, he became the first second-year student to be named Senior Wrangler. This was a very high honor in math. After getting his master's degree in 1905, he started research at the Cavendish Laboratory. This research didn't go well. But soon, he got a job at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. This is where his career in astronomy truly began.

Contributions to Astronomy

In 1906, Eddington became the chief assistant at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. He worked on studying the parallax (how objects seem to shift when viewed from different angles) of a small planet called 433 Eros. He created a new way to analyze the data. This work won him the Smith's Prize in 1907.

In 1913, he became the Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at Cambridge. The next year, he was made the director of the entire Cambridge Observatory. In 1914, he became a fellow of the Royal Society, a very important scientific group. He received the Royal Medal in 1928.

Eddington also studied the inside of stars. He developed the first real understanding of how stars work. He started this in 1916 by looking at Cepheid variable stars. These stars change brightness regularly. He showed that radiation pressure (the push from light) was important to stop stars from collapsing. He figured out the temperature, density, and pressure inside a star.

He also made an important discovery called the mass–luminosity relation. This showed that almost all stars, big or small, act like ideal gases. He believed that stars get their energy from nuclear fusion. This is where light elements like hydrogen combine to form heavier ones like helium. This process releases a huge amount of energy, as described by Einstein's famous equation, E = mc2.

This idea was amazing because fusion and thermonuclear energy were not yet discovered. Also, scientists didn't even know that stars were mostly made of hydrogen. Eddington's paper explained that:

- The old idea that stars got energy from shrinking didn't fit observations.

- Einstein's theory showed that matter could turn into energy.

- Scientists had found that a helium atom weighed slightly less than four hydrogen atoms. This meant if hydrogen turned into helium, energy would be released.

- If a star had just 5% hydrogen, it could explain its energy. (We now know stars have much more hydrogen.)

All these ideas were proven correct later on. His work was published in his 1926 book, The Internal Constitution of the Stars. This book became very important for future astrophysicists.

Debate on Black Holes

Eddington had a famous disagreement with his student, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. Chandrasekhar's work suggested the existence of black holes. At the time, black holes seemed too strange to be real. Eddington found it hard to believe that Chandrasekhar's math could lead to such a wild idea. Eddington was wrong, and black holes are now a key part of astronomy.

Relativity and the Eclipse Expedition

During World War I, Eddington was the secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society. This meant he was among the first to read about Einstein's theory of general relativity. Eddington was one of the few scientists who understood the complex math of this theory. He was also a Quaker and a pacifist. This meant he was interested in a theory from a German physicist, even during wartime. He quickly became the main supporter of relativity in Britain.

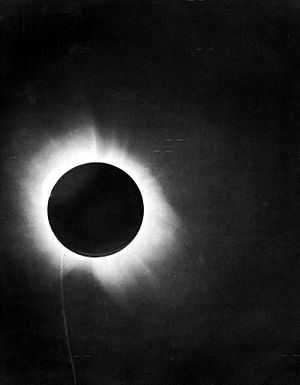

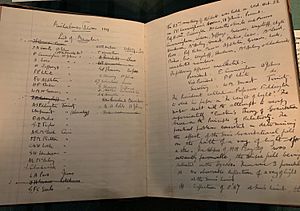

He and Astronomer Royal Frank Watson Dyson planned two expeditions to observe a solar eclipse in 1919. The goal was to test Einstein's theory. Einstein's theory predicted that the Sun's gravity would bend starlight passing near it. This would make the stars appear slightly shifted. Dyson argued that Eddington's skills were essential for this test. This helped Eddington avoid military service during the war.

After the war, Eddington traveled to the island of Príncipe, off the coast of Africa. He took pictures of stars during the eclipse. These stars were normally hidden by the Sun's brightness. When he compared the pictures, he found that the stars' positions had shifted. This shift matched Einstein's predictions.

The news of this confirmation spread worldwide. Eddington then worked to explain relativity to everyone. Some people later questioned the quality of his observations. However, a re-analysis in 1979 using modern tools confirmed his results.

Eddington gave many lectures on relativity. He was known for explaining difficult ideas clearly. His book, The Mathematical Theory of Relativity (1923), was praised by Einstein himself. It was considered the best explanation of the subject.

Cosmology and Fundamental Theory

Eddington also helped develop early models of the universe based on general relativity. He studied how the universe might be changing. He learned about Lemaître's idea of an expanding universe. He also knew about Hubble's work on galaxies moving away from us. Eddington believed that a special constant, called the cosmological constant, was key to how the universe evolved.

From the 1920s until his death, Eddington focused on what he called "fundamental theory." He wanted to combine quantum theory, relativity, and gravity into one big theory. He looked at how different basic constants in physics relate to each other.

He thought that the mass of the proton and the charge of the electron were essential for building a universe. He believed their values were not random. He even suggested a specific value for the fine-structure constant, a key number in physics. This number is sometimes called the Eddington number.

Eddington Number for Cycling

Eddington also created a fun way to measure a cyclist's long-distance achievements. The Eddington number for cycling is the highest number 'E' where a cyclist has ridden at least 'E' miles on at least 'E' different days.

For example, if your Eddington number is 70, it means you have cycled 70 miles or more on at least 70 separate days. Getting a high Eddington number is hard! Eddington's own cycling number was 84. This idea is similar to the h-index used to measure a scientist's research impact.

Philosophy and Popular Writings

Eddington wrote in his book The Nature of the Physical World that "The stuff of the world is mind-stuff." He meant that our understanding of the world comes from our minds. He believed that the physical world and our minds are connected.

Eddington also argued against determinism. This is the idea that everything is already decided. He believed that there is a part of nature that is truly uncertain. This idea is linked to the uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics. He thought this uncertainty meant there was room for human freedom.

Eddington wrote a funny poem about his 1919 solar eclipse experiment:

Oh leave the Wise our measures to collate

One thing at least is certain, LIGHT has WEIGHT,

One thing is certain, and the rest debate—

Light-rays, when near the Sun, DO NOT GO STRAIGHT.

He gave many lectures and radio broadcasts about relativity and quantum mechanics. Many of these were put into books like The Nature of the Physical World. He used humor and stories to make these complex topics easier to understand.

His books were very popular. He talked about how science and religious ideas could fit together. He believed that new physics allowed for personal religious experiences and free will. He did not think science could prove religious ideas, but that they could exist in harmony.

He is sometimes linked to the infinite monkey theorem. In one of his books, he wrote: "If an army of monkeys were strumming on typewriters, they might write all the books in the British Museum." He used this to show that some things are so unlikely they are practically impossible.

His popular writings made him a well-known name in Great Britain.

Death and Legacy

Arthur Eddington died from cancer on November 22, 1944, in Cambridge. He was not married. He was cremated, and his ashes were buried with his mother in Cambridge.

A new area in Cambridge, called Eddington, is named in his honor.

The actor Paul Eddington was a relative of Sir Arthur. Paul once joked about his own struggles with math, saying it was a "misfortune" to be related to "one of the foremost physicists in the world."

Honours

Awards

- Smith's Prize (1907)

- Bruce Medal of Astronomical Society of the Pacific (1924)

- Henry Draper Medal of the National Academy of Sciences (1924)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1924)

- Foreign membership of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (1926)

- Prix Jules Janssen of the Société astronomique de France (French Astronomical Society) (1928)

- Royal Medal of the Royal Society (1928)

- Knighthood (1930)

- Order of Merit (1938)

- Honorary member of the Norwegian Astronomical Society (1939)

- Hon. Freeman of Kendal, 1930

Named after him

- Lunar crater Eddington

- asteroid 2761 Eddington

- Royal Astronomical Society's Eddington Medal

- Eddington mission, now cancelled

- Eddington Tower, halls of residence at the University of Essex

- Eddington Astronomical Society, an amateur society based in his hometown of Kendal

- Eddington, a house (group of students, used for in-school sports matches) of Kirkbie Kendal School

- Eddington, new suburb of North West Cambridge, opened in 2017

Service

- Gave the Swarthmore Lecture in 1929

- Chairman of the National Peace Council 1941–1943

- President of the International Astronomical Union; of the Physical Society, 1930–32; of the Royal Astronomical Society, 1921–23

- Romanes Lecturer, 1922

- Gifford Lecturer, 1927

See Also

In Spanish: Arthur Stanley Eddington para niños

In Spanish: Arthur Stanley Eddington para niños

Astronomy

- Chandrasekhar limit

- Eddington luminosity (also called the Eddington limit)

- Gravitational lens

- Outline of astronomy

- Stellar nucleosynthesis

- Timeline of stellar astronomy

- List of astronomers

Science

- Arrow of time

- Classical unified field theories

- Degenerate matter

- Dimensionless physical constant

- Dirac large numbers hypothesis (also called the Eddington–Dirac number)

- Eddington number

- Introduction to quantum mechanics

- Luminiferous aether

- Parameterized post-Newtonian formalism

- Special relativity

- Theory of everything (also called "final theory" or "ultimate theory")

- Timeline of gravitational physics and relativity

- List of experiments

People

- List of science and religion scholars

Other

- Infinite monkey theorem

- Numerology

- Ontic structural realism