Du Fu facts for kids

| Du Fu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

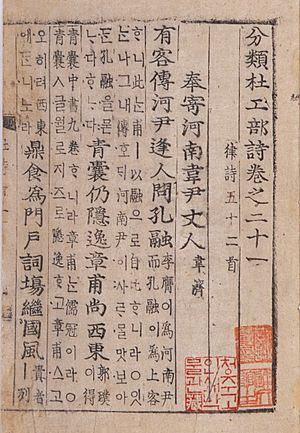

Du's name in Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 杜甫 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 子美 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Art name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 少陵野老 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 杜甫 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | とほ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Du Fu (Chinese: 杜甫; Wade–Giles: Tu Fu; 712–770) was a famous Chinese poet and government official during the Tang dynasty. Many people consider him one of the greatest Chinese poets ever, often mentioned alongside his friend Li Bai. Du Fu really wanted to serve his country as a successful civil servant, which is a person who works for the government.

However, his life, and the whole country, changed drastically because of the An Lushan Rebellion in 755. This was a huge uprising that caused a lot of trouble. After this, Du Fu spent his last 15 years moving around and facing many challenges. Even though he wasn't very well-known to other writers at first, his poems later became very important in both Chinese and Japanese literature. We still have almost 1,500 of his poems today. Chinese experts have called him the "Poet-Historian" and the "Poet-Sage" because his poems often talk about history and wisdom.

Contents

Du Fu's Life Story

To understand Du Fu's poems, it helps to know about his life. This is because Chinese experts believe that an artist's life is closely connected to their art. Also, Du Fu's poems are often short, so knowing the background helps us understand them better.

Growing Up

Most of what we know about Du Fu comes from his own poems. He was born in 712, but we don't know the exact place, only that it was near Luoyang, in Henan province. His grandfather, Du Shenyan, was also a famous poet and politician.

Du Fu's mother passed away soon after he was born. He was partly raised by his aunt. He had an older brother who died young, and also three half-brothers and one half-sister. He often wrote about them in his poems.

As the son of a government official, Du Fu studied hard to become a civil servant himself. This meant learning about Confucian classics, history, and poetry. He said he wrote good poems even as a teenager, but those poems are now lost.

In the early 730s, Du Fu traveled around China. His oldest poem that we still have is from around 735. In that same year, he took an important test called the Imperial examination to become a government official. Surprisingly, he failed! After this, he continued traveling.

His father died around 740. Du Fu could have joined the government because of his father's position, but he chose to let one of his half-brothers have that chance instead. For the next four years, he lived in the Luoyang area, taking care of family matters.

In 744, he met Li Bai for the first time, and they became good friends. This friendship was very important for Du Fu's writing. Li Bai was already a famous poet, and Du Fu looked up to him. Du Fu wrote many poems about Li Bai, but Li Bai only wrote one about Du Fu. They met only once more, in 745.

In 746, Du Fu moved to the capital city, Chang'an, to try and restart his career. He took the civil service exam again, but everyone failed because the prime minister didn't want any new rivals. Du Fu never tried the exams again. Instead, he wrote directly to the emperor several times, asking for a job.

He got married around 752. By 757, he and his wife had five children, but one son died as a baby in 755. Around 754, Du Fu started having lung problems, possibly asthma. This was the start of many health issues he would face. That same year, he had to move his family because of a famine caused by big floods.

In 755, he finally got a small job in the Crown Prince's Palace. But before he could even start, a big war began.

Times of War

The An Lushan Rebellion started in December 755 and lasted for almost eight years. It caused huge problems for China. Millions of people were displaced or killed. During this time, Du Fu moved around a lot because of the wars, famines, and problems with the emperor.

This difficult time actually made Du Fu a better poet. He wrote about what he saw around him: the lives of his family, neighbors, and strangers. He wrote about his hopes and fears during the war. Even when his youngest child died, he focused on the suffering of others in his poems, not just his own sadness.

In 756, Emperor Xuanzong had to leave the capital. Du Fu tried to join the new emperor's court, but rebels captured him and took him to Chang'an. His youngest son was born around this time. Du Fu also got sick with malaria.

He escaped from Chang'an in 757 and rejoined the court. He got a ceremonial job that allowed him to see the emperor. Du Fu was very dedicated and tried to use his position to help. He got into trouble for defending a friend who was wrongly accused. He was arrested but later pardoned.

In 758, he was moved to a less important job as Commissioner of Education. He didn't like this job at all. He wrote in a poem:

束帶發狂欲大叫,

簿書何急來相仍。

I am about to scream madly in the office,

Especially when they bring more papers to pile higher on my desk.

He left this job in 759, probably because he was frustrated. He then spent about six weeks in Qinzhou, where he wrote over sixty poems.

Life in Chengdu

In December 759, Du Fu arrived in Chengdu (Sichuan province). He stayed there for most of the next five years. He had money problems at first, but a friend named Yan Wu, who was a governor, helped him financially.

Despite his money troubles, this was one of the happiest and most peaceful times in his life. Many of Du Fu's poems from this period describe his calm life at his Du Fu Thatched Cottage. In 762, he left the city to avoid a rebellion, but he returned in 764 and became an advisor to Yan Wu.

Final Years

In 762, the government took back Luoyang, Du Fu's birthplace. In 765, Du Fu and his family sailed down the Yangtze, planning to go back home. They traveled slowly because Du Fu was very sick. He had poor eyesight, couldn't hear well, and was generally old and unwell.

They stayed in Kuizhou for almost two years. This time was very important for his poetry. He wrote 400 poems here in his unique, later style. In 766, a new governor, Bo Maolin, supported Du Fu and hired him as his unofficial secretary.

In 768, Du Fu continued his journey and reached Hunan province. He passed away in November or December 770, at 58 years old. His wife and two sons survived him.

One expert described Du Fu as "a loyal son, a loving father, a generous brother, a faithful husband, a loyal friend, a dutiful official, and a patriotic citizen."

Here is one of Du Fu's later poems, "To My Retired Friend Wei" (Zēng Wèi Bā Chǔshì 贈衛八處士). It talks about friends being separated for a long time, which was common for officials who often moved:

人生不相見, It is almost as hard for friends to meet

動如參與商。 As for the Orion and Scorpius.

今夕復何夕, Tonight then is a rare event,

共此燈燭光。 Joining, in the candlelight,

少壯能幾時, Two men who were young not long ago

鬢髮各已蒼。 But now are turning grey at the temples.

訪舊半為鬼, To find that half our friends are dead

驚呼熱中腸。 Shocks us, burns our hearts with grief.

焉知二十載, We little guessed it would be twenty years

重上君子堂。 Before I could visit you again.

昔別君未婚, When I went away, you were still unmarried;

兒女忽成行。 But now these boys and girls in a row

怡然敬父執, Are very kind to their father's old friend.

問我來何方。 They ask me where I have been on my journey;

問答乃未已, And then, when we have talked awhile,

兒女羅酒漿。 They bring and show me wines and dishes,

夜雨翦春韭, Spring chives cut in the night-rain

新炊間黃粱。 And brown rice cooked freshly a special way.

主稱會面難, My host proclaims it a festival,

一舉累十觴。 He urges me to drink ten cups—

十觴亦不醉, But what ten cups could make me as drunk

感子故意長。 As I always am with your love in my heart?

明日隔山嶽, Tomorrow the mountains will separate us;

世事兩茫茫。 After tomorrow—who can say?

Du Fu's Health

Du Fu is one of the first people in history known to have diabetes. In his later years, he also suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, a lung disease. He died on a ship on the Yangtze River when he was 58 years old.

Du Fu's Amazing Poems

Experts who study Du Fu's poems often talk about his strong connection to history, his sense of right and wrong, and how incredibly skilled he was at writing.

Poems About History

Since the Song Dynasty, people have called Du Fu the "poet saint" (詩聖, shī shèng). His most historical poems talk about military strategies, or how well the government was doing. He also wrote poems giving advice to the emperor.

He also wrote about how the difficult times he lived in affected him and ordinary people. This gives us information that isn't usually found in official history books. Du Fu's political ideas came from his feelings, not just calculations. He believed people should be less selfish and do what they are supposed to do.

Moral Messages in Poetry

Another common name for Du Fu is "poet sage" (詩聖, shī shèng). This is like calling him a wise philosopher, similar to Confucius. One of his earliest poems, The Song of the Wagons (around 750), describes the suffering of a soldier forced to join the army. Du Fu continued to write about the hardships of soldiers and regular people throughout his life.

Even though Du Fu often mentioned his own problems, his famous kindness actually included himself. He used his own small struggles to make the bigger picture of suffering seem even more important. Du Fu's kindness helped him write about many new topics in poetry that people hadn't written about before. He wrote about everyday life, calligraphy, paintings, animals, and even other poems.

How Du Fu Wrote So Well

Du Fu's work is special because of how varied it is. Chinese experts use a term that means "complete symphony" to describe his work, comparing him to Confucius. One early writer, Yuan Zhen, said in 813 that Du Fu "combined in his work qualities that previous men had shown only one by one."

Du Fu mastered all the different types of Chinese poetry. He made great improvements or wrote amazing examples in every form. His poems also use many different styles of language, from simple and everyday words to more complex and literary ones. This variety can even be seen within a single poem. Du Fu wrote more about poetry and painting than any other writer of his time. He wrote eighteen poems just about painting.

His writing style changed as he grew and adapted to his surroundings. His early poems were more traditional, but he really found his voice during the rebellion. Poems from his time in Qinzhou are simple and reflect the desert landscape. His Chengdu poems are light and observant. The poems from his later years in Kuizhou are very deep and powerful.

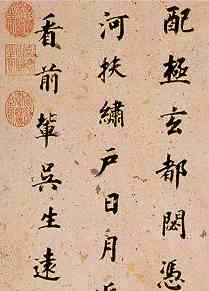

Although he wrote in all poetic forms, Du Fu is most famous for his lǜshi, which is a type of poem with strict rules for its form and content. Here's an example:

窈窕清禁闥,

罷朝歸不同。

君隨丞相後,

我往日華東。

Leaving the Audience by the quiet corridors,

Stately and beautiful, we pass through the Palace gates,

Turning in different directions: you go to the West

With the Ministers of State. I, otherwise.

冉冉柳枝碧,

娟娟花蕊紅。

故人得佳句,

獨贈白頭翁。

On my side, the willow-twigs are fragile, greening.

You are struck by scarlet flowers over there.

Our separate ways! You write so well, so kindly,

To caution, in vain, a garrulous old man.

About two-thirds of Du Fu's 1,500 surviving poems are in this lǜshi form, and he is considered the best at it. His best lǜshi poems use the required parallel lines to add meaning, not just as a technical rule. It's amazing how naturally he used such a strict form.

Du Fu's Lasting Influence

Many literary experts believe Du Fu's writings are among the greatest of all time. His language is very rich and uses all the hidden meanings of words, which is why it's hard to translate perfectly.

During his lifetime and right after his death, Du Fu wasn't widely famous. This might be because his writing style was new and daring for his time. There are only a few mentions of him by other writers from that period, and they describe him as a friend, not as a perfect poet. He also wasn't included much in poetry collections back then.

However, as one expert noted, Du Fu "is the only Chinese poet whose influence grew with time." His poems became more popular in the 9th century. Later, in the 11th century during the Song Dynasty, Du Fu's reputation reached its peak. He became known as the most important poet representing Confucianism in Chinese culture.

His influence grew because he could bring together different ideas. People who liked traditional ways were drawn to his loyalty to the government. People who wanted change liked his concern for the poor. Writers who liked traditional styles admired his technical skill, while those who liked new ideas were inspired by his creativity. In modern China, Du Fu's loyalty to the state and care for the poor are seen as early signs of nationalism and socialism, and he is praised for using simple, everyday language.

Du Fu's popularity became so great that it's hard to measure his influence, much like how hard it is to measure Shakespeare's influence in England. It was almost impossible for any Chinese poet not to be influenced by him. While there was never another Du Fu, many poets followed parts of his style: Bai Juyi cared for the poor like Du Fu, Lu You showed patriotism, and Mei Yaochen wrote about daily life. More generally, Du Fu's work changed the lǜshi poem form from just word games into a way to express serious ideas, setting the stage for all future writers in that style.

One publisher said that Du Fu "has been called China's greatest poet, and some call him the greatest non-epic, non-dramatic poet whose writings survive in any language."

Impact on Japanese Literature

Du Fu's poetry had a huge impact on Japanese literature, especially during the Muromachi period and on scholars and poets in the Edo period. This includes Matsuo Bashō, who is considered the greatest haiku poet. Even in modern Japanese, the term Saint of Poetry (詩聖, shisei) usually refers to Du Fu.

Until the 13th century, the Japanese preferred the poet Bai Juyi. But then, a Zen master named Kokan Shiren (1278–1346) praised Du Fu highly. His students and their students continued to spread Du Fu's poetry. Soon, Du Fu's poems were often mentioned in Japanese literature.

During the Edo period (1624–1643), a Chinese book of comments on Du Fu's poems became very popular in Japan. This book made Du Fu famous as the greatest of all poets. Matsuo Bashō, the famous haiku poet, was also greatly influenced by Du Fu. In his masterpiece, Oku no Hosomichi, he quotes Du Fu's poem "A Spring View" and many of his own haiku have similar words and themes. It is said that when Bashō died, a copy of Du Fu's poetry was found with him, showing how much he valued it.

Translating Du Fu's Poems

Translating Du Fu's poems into English has been a challenge because of his unique style. As translator Burton Watson said, "There are many different ways to approach the problems involved in translating Du Fu, which is why we need as many different translations as possible." Translators have to make sure the formal rules of the original poems don't sound awkward in English. They also have to deal with the many complex hints and references in his later works.

Some translators, like Kenneth Rexroth, use very free translations. They try to hide the parallel lines and simplify the references. Other translators try to keep more of the original poetic forms. Vikram Seth uses English rhymes, while Keith Holyoak tries to match the Chinese rhyme scheme. Both keep the lines separate and some of the parallel structure.

Burton Watson tries to follow the parallel lines very closely, expecting the English reader to get used to the Chinese style. He also explains the references in the later poems with many notes. Other translators like Arthur Cooper and David Hinton have also published selected poems. In 2015, Stephen Owen published a complete translation of Du Fu's poetry in six volumes, with the original Chinese text next to the English.

See also

In Spanish: Du Fu para niños

In Spanish: Du Fu para niños