Evolution of Hawaiian volcanoes facts for kids

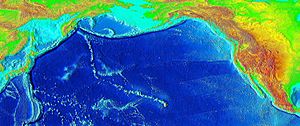

The Hawaiian Islands are home to fifteen volcanoes. These volcanoes are the youngest in a long line of over 129 volcanoes. This chain stretches 5,800 kilometres (3,600 mi) across the North Pacific Ocean. It is called the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain. Hawaii's volcanoes rise about 4,600 metres (15,000 ft) from the ocean floor to reach sea level. The biggest one, Mauna Loa, is 4,169 metres (13,678 ft) tall. These volcanoes are called shield volcanoes. They are built up by many layers of lava flows. This makes them wide with gentle slopes, growing a little bit at a time.

Hawaiian islands go through different stages as they grow and then wear away. An island's stage depends on how far it is from the Hawaii hotspot.

Contents

- How Hawaiian Volcanoes Form

- Underwater Start: The Preshield Stage

- Building Up: The Shield Stages

- Slowing Down: Postshield Stage

- Wearing Away: Erosional Stage

- Waking Up Again: Rejuvenated Stage

- Truly Dead: Extinct Stage

- Coral Ring: Atoll Stage

- Flat-Topped Underwater Mountains: Guyot Stage

- Other Patterns

- Similarities Elsewhere

How Hawaiian Volcanoes Form

The Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain is very long and has many volcanoes. It's split into two parts. The older part is the Emperor Seamount Chain, and the younger part is the Hawaiian Ridge. You can easily see a "V" shape where they meet on maps. The volcanoes get younger as you move southeast. The oldest volcano found is 81 million years old. The bend in the chain happened about 43 million years ago. For comparison, the oldest main Hawaiian island, Kauaʻi, is just over 5 million years old.

These volcanoes are formed by a "hotspot." This is a super hot spot deep inside the Earth that sends up magma. This magma then becomes lava when it reaches the surface. The Pacific Plate (a huge piece of Earth's crust) slowly moves northwest. As it moves, each volcano moves away from the hotspot. The age and location of the volcanoes show us how the Pacific Plate has moved over time. The big bend 43 million years ago shows a major change in the plate's direction.

When volcanoes first erupt deep underwater, they create pillow lava. This lava looks like rounded pillows. When eruptions happen in shallow water, they often produce volcanic ash. Once a volcano grows tall enough to be above water, its lava flows become ropey pāhoehoe and blocky ʻAʻā lava.

Scientists have learned a lot about how these volcanoes grow by watching eruptions and studying rocks. Modern tools like special underwater studies and advanced monitoring have helped even more.

Other things also affect how volcanoes grow and shrink. The land can sink because of the volcano's huge weight. Changes in sea level, especially during the Ice Age, also caused big changes. For example, Maui Nui, which was once one big island with seven volcanoes, split into five islands because of the land sinking. Heavy rainfall from trade winds also wears down the volcanoes. Sometimes, large parts of the volcanoes can collapse into the ocean.

Underwater Start: The Preshield Stage

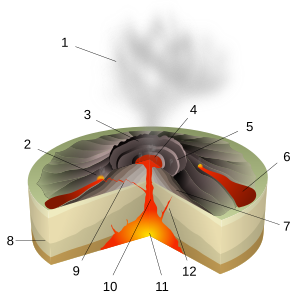

When a volcano starts to form near the Hawaiian hotspot, it begins in the submarine preshield stage. "Submarine" means underwater. During this stage, eruptions are not very often and don't produce a lot of lava. The volcano is steep and usually has a bowl-shaped caldera at its top. It also has two or more rift zones, which are cracks where lava can erupt. The lava erupted here is a type called alkali basalt.

Because the volcano is underwater, the lava forms pillow lava. This lava cools very quickly when it touches the cold ocean water, forming rounded shapes. The water pressure also stops the lava from exploding. This stage is thought to last about 200,000 years. The lava from this stage makes up only a tiny part of the volcano's final size. As time goes on, eruptions become stronger and happen more often.

The only Hawaiian volcano currently in this stage is Lōʻihi Seamount. Scientists believe it is moving into the next stage. All older volcanoes have had their preshield lavas covered by newer lavas. So, most of what we know about this stage comes from studying Lōʻihi.

Building Up: The Shield Stages

The shield stage is when the volcano grows most of its size, about 95% of its total mass. It also gets its wide, gently sloping "shield" shape during this time. This is when the volcano erupts most often. This stage has three phases: submarine, explosive, and subaerial.

Underwater Growth: Submarine Phase

As eruptions become more frequent, the lava changes. The volcano keeps erupting pillow lava. Calderas form and fill up at the top, and the rift zones stay active. The volcano builds itself up towards sea level. This phase ends when the volcano is just below the surface of the water.

Again, Lōʻihi Seamount is the only volcano currently transitioning into this phase.

Big Splashes: Explosive Phase

This phase is called "explosive" because of the reactions that happen when lava meets water. It starts when the volcano just breaks the surface of the ocean. The pressure from being underwater is gone, and the lava now touches air. Lava and seawater mix, creating a lot of steam. This change also makes the lava break into small pieces, forming volcanic ash. These explosive eruptions happen on and off for hundreds of thousands of years. Calderas keep forming and filling, and rift zones are still active. This phase ends when the volcano is tall enough (about 1,000 metres (3,000 ft) above sea level) that the lava no longer mixes with seawater.

Above Water: Subaerial Phase

Once the volcano is tall enough to be mostly out of the water, the subaerial stage begins. "Subaerial" means above air. During this stage, the explosive eruptions become much less common. The eruptions become gentler. The lava flows are a mix of pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā. This is when the volcano gets its low, wide "shield" shape, like a warrior's shield lying on the ground. Eruptions happen very often and produce a lot of lava. About 95% of the volcano's total size forms during this stage, which lasts about 500,000 years.

The sides of these growing volcanoes can be unstable. Large landslides can happen. At least 17 major landslides have occurred around the main Hawaiian islands. This stage is well-studied because all recent eruptions on the island of Hawaii have come from volcanoes in this phase.

Mauna Loa and Kīlauea volcanoes are currently in this active stage.

Slowing Down: Postshield Stage

As the volcano finishes its shield stage, it enters the postshield stage. The type of lava changes, and eruptions become a bit more explosive. Research shows that the eruption rates of these volcanoes started to slow down between 600,000 and 400,000 years ago.

Lava in this stage covers the volcano with a different type of rock. These lavas are often thick and pasty ʻaʻā flows, along with a lot of cinder. Calderas stop forming, and the rift zones become less active. The new lava flows make the volcano's slopes steeper because the ʻaʻā lava doesn't flow all the way to the base. These lavas often fill and overflow the caldera. Eruptions slowly decrease over about 250,000 years. Eventually, they stop completely, and the volcano becomes dormant (sleeping).

Mauna Kea, Hualālai, and Haleakalā volcanoes are in this stage.

Wearing Away: Erosional Stage

After the volcano becomes dormant, erosion takes over. The volcano starts to sink into the ocean floor because of its huge weight. It also loses height. Meanwhile, rain wears down the volcano, creating deep valleys. Coral reefs grow along the shoreline. The volcano becomes a worn-down version of its former self.

Kohala, Māhukona, Lānaʻi, and Waiʻanae volcanoes are examples of volcanoes in this stage.

Waking Up Again: Rejuvenated Stage

After a long time of being dormant and eroding, a volcano might become active again. This is its final stage, called the rejuvenated stage. During this stage, the volcano erupts small amounts of lava very rarely. These eruptions can be millions of years apart. The lava is usually a type called alkalic. This stage often happens between 0.6 and 2 million years after the volcano started eroding.

Koʻolau Range, West Maui, and Kahoʻolawe volcanoes are in this stage. However, because eruptions are so rare in this stage, erosion is still the main force shaping the volcano.

Truly Dead: Extinct Stage

After the rejuvenated stage, the volcano is too far from the hotspot to get new magma. This means it will never erupt again. The volcano continues to sink into the ocean and gets deeply eroded. This can lead to large collapses of its original structure. The volcano has no magma left inside and is truly dead.

West Molokaʻi, Kaʻena Ridge, Waiʻaleʻale, Niʻihau, and Kaʻula volcanoes are in this stage.

Coral Ring: Atoll Stage

Eventually, erosion and sinking break the volcano down until it is at sea level. At this point, the volcano becomes an atoll. An atoll is a ring of coral and sand islands surrounding a calm lagoon. All the Hawaiian islands west of the Gardner Pinnacles in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are now atolls.

Flat-Topped Underwater Mountains: Guyot Stage

Atolls form because of the growth of tropical marine organisms like coral. So, atolls are only found in warm tropical waters. As the Pacific Plate carries the atoll into colder waters, the coral cannot grow anymore. The volcano then sinks or erodes below sea level and becomes a coral-capped underwater mountain. These flat-topped underwater mountains are called guyots. Most of the volcanoes west of Kure Atoll and in the Emperor Seamount chain are now guyots or seamounts.

Other Patterns

Not all Hawaiian volcanoes go through every single stage. For example, Koʻolau Range on Oʻahu was hit by a huge landslide long ago. It skipped the postshield stage and went dormant after its shield stage before becoming active again. Some volcanoes never even made it above sea level. It's not known what stage the underwater volcano of Penguin Bank is in.

Similarities Elsewhere

Recent research on other underwater mountains, like Jasper Seamount, has shown that this Hawaiian volcano life cycle model also applies to volcanoes in other parts of the world.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |