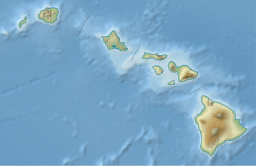

Kohala (mountain) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kohala |

|

|---|---|

Kohala volcano as seen from Mauna Kea

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,480 ft (1,670 m) |

| Prominence | 2,600 ft (790 m) |

| Naming | |

| Language of name | Hawaiian |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Hawaiian Islands |

| Topo map | USGS Kamuela |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | >1,000,000 years |

| Mountain type | Shield volcano, Hotspot volcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain |

| Last eruption | About 120,000 years ago |

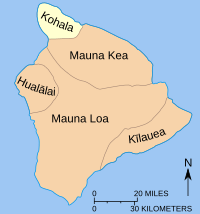

Kohala is the oldest of the five volcanoes that form the Big Island of Hawaii. It's about one million years old! This volcano is so ancient that it even recorded a flip in Earth's magnetic field 780,000 years ago.

Scientists believe Kohala rose above sea level over 500,000 years ago. Its last eruption was around 120,000 years ago. Kohala covers an area of 606 square kilometers (234 sq mi). It has a volume of 14,000 cubic kilometers (3,400 cu mi). This means it makes up almost 6% of the Big Island.

Kohala is a shield volcano. It has many deep gorges carved into it. These gorges were formed by thousands of years of erosion. Unlike other Hawaiian volcanoes, Kohala has a unique foot-like shape. About 250,000 to 300,000 years ago, a huge landslide happened. It destroyed the volcano's northeast side. This slide reduced its height by over 1,000 meters (3,300 ft). The debris traveled 130 kilometers (81 mi) across the sea floor. This massive landslide might be why the volcano looks like a foot.

Marine fossils have been found high up on the volcano's side. They were too high to be left by normal ocean waves. Studies showed these fossils were deposited by a giant tsunami. This tsunami happened about 120,000 years ago.

Because Kohala is so far from any big landmass, its ecosystem is special. It has many unique plants and animals. Efforts are being made to protect this ecosystem. They want to keep out invasive species. Farmers have grown crops, especially sweet potato, on the volcano's leeward side for centuries. The northern part of the island is named after the mountain. It has two districts: North and South Kohala. King Kamehameha I, the first King of the Kingdom of Hawaii, was born in North Kohala. This was near Hawi.

Contents

Understanding Kohala's Geology

How Kohala Formed

Scientists have studied how fast lava built up on Kohala. This suggests the volcano is about one million years old. It likely rose above sea level more than 500,000 years ago. Around 300,000 years ago, the volcano's eruptions slowed down. At this point, erosion started wearing it down faster than new lava could build it up. This led to Kohala slowly shrinking and sinking into the ocean.

The oldest lava flows we can still see are almost 780,000 years old. It's hard to know Kohala's original size and shape. This is because lava from nearby Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa has covered its southeast side. However, scientists believe Kohala was once about twice its current size.

Kohala is so old that it recorded a magnetic polarity reversal. This is when Earth's magnetic poles switch places. This event happened 780,000 years ago. Lava flows from the top 140 meters (460 ft) of rock show normal polarity. This means they were laid down within the last 780,000 years.

Between 250,000 and 300,000 years ago, a huge landslide hit Kohala. Debris from this slide was found 130 kilometers (81 mi) away on the ocean floor. The landslide was 20 kilometers (12 mi) wide at the coast. It reached all the way to the volcano's summit. This event caused Kohala to lose 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) in height. The famous sea cliffs along Kohala's coast are proof of this disaster. They show the top part of the ancient landslide debris.

Kohala is thought to have last erupted 120,000 years ago. However, some lava samples have been found that seem younger. Two samples from Waipiʻo Valley were dated to 60,000 years old. Other samples from the west side were measured at 80,000 years old. Scientists are still debating these younger dates.

In 2004, marine fossils were found 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) inland at the base of the volcano. A research team found that a huge tsunami had deposited these fossils. They were 61 meters (200 ft) above the current sea level. The fossils and nearby rock were dated to about 120,000 years old. This timing matches a big landslide from nearby Mauna Loa. Researchers think this underwater landslide caused the giant tsunami. The tsunami then swept up coral and other sea life. It left them on Kohala's western side.

How Kohala is Built

Kohala had two active rift zones. These are common features of Hawaiian volcanoes. The two ridges were active during both the volcano's early and later stages. One rift zone goes under Mauna Kea. It then reappears further southeast. This is shown by studies of lava samples.

Geologists have divided the volcano's lava flows into two main groups. The younger Hawi Volcanic layers formed in the volcano's later stage. The older Pololu Volcanics formed during its shield-building stage. The Hawi rock is mostly 260,000 to 140,000 years old. It is made of types of lava called hawaiite and trachyte.

The forest-covered summit of Kohala has many cones. These cones produced lava from its two rift zones between 240,000 and 120,000 years ago. Kohala finished its main shield-building stage 245,000 years ago. It has been shrinking ever since. Scientists believe it last erupted about 120,000 years ago. Kohala is now in a stage where it is being worn down by erosion.

The United States Geological Survey says Kohala is a low-risk area. It is in zone 9, which is the safest zone. The area where Kohala meets Mauna Kea is zone 8. This is because Mauna Kea has not erupted for 4,500 years.

Kohala, like other shield volcanoes, has gentle slopes. This is because the lava that formed it was very runny. However, its northwest coast has some of the tallest sea cliffs on Earth. The volcano's unique foot-like shape and other features are likely due to the ancient landslide. The northeast coast has a noticeable indentation across 20 kilometers (12 mi) of shoreline.

There are small faults near the main summit caldera. They run parallel to the northern coast. These faults might have been caused by the sudden release of stress during the landslide.

Water on Kohala Mountain

Mauna Kea causes trade winds to go around it. This increases wind over the Kohala ridge. This also causes a lot of rain to fall on Kohala's northeastern slope. The rainy side of Kohala mountain has many deep stream valleys. These valleys cut into the volcano's sides. North of Kohala's summit, the volcano's rift zone divides rainfall. Water flows southeast into Waipiʻo Valley or northwest into Honokane Nui Valley.

When the volcano was active, sheets of magma called dikes pushed up through the rift zone. As these dikes rose, they created cracks and faults. These faults formed horsts and grabens (fault blocks). In the rainiest area, these faults stop rainwater from flowing straight down the mountain. Instead, the water flows sideways. It then empties into the back of the largest valleys, like Waipiʻo and Honokane Nui.

The drier, northwestern side of Kohala has few stream valleys. This is due to the rain shadow effect. The main trade winds bring most rain to the northeastern side. Kohala's seven rainy valleys are Waipiʻo, Waimanu, Honopue, Honokea, Honokane Iki, Honokane Nui, and Pololu. The size of the valleys shows how much water they collect. Waipiʻo, the largest, once drained Waimanu Valley too.

The depth of the valley walls at the coast ranges from 300 meters (980 ft) at Waipiʻo Valley Lookout. It goes up to over 500 meters (1,600 ft) in Honopue. Then it shrinks to less than 150 meters (490 ft) at Pololu Lookout. Deeper inside the mountain, all valleys have sheer walls over 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) high. Many amazing waterfalls tumble over these cliffs. Some, like Hi'ilawe Falls in Waipiʻo Valley, drop over 300 meters (980 ft) in one fall.

The volcano was still active when these valleys formed. Later lava flows covered the north and northwest parts of Kohala. They often flowed into Pololu Valley. Seafloor maps show that Pololu Valley extends past the coast. It then ends at what might be the edge of the great landslide.

The dikes near the summit are important for the water table. Hawaiian lava is very porous. Rainwater easily soaks into it. This creates a large layer of fresh water underground. Dikes are dense rock walls that trap this groundwater. This means rainwater gets held in these dike "reservoirs" above sea level.

Most of Kohala's summit groundwater ends up in Waipiʻo or Honokane Nui. This huge amount of water causes a lot of water erosion. This makes the valley walls often collapse. This speeds up how fast the valleys grow. This abundance of surface water led to the first of Kohala's irrigation "ditches." The Upper Hamakua Ditch was first used to transport sugarcane. Later, other ditches tapped into springs for larger farms.

Kohala's Unique Ecosystem

The natural habitats in Kohala change a lot over a short distance. Rainfall goes from less than 5 inches (130 mm) a year near the coast to over 150 inches (3,800 mm) near the summit. This is a distance of only 11 miles (18 km). The coast has remnants of dry forests. Near the summit is a cloud forest. This type of rainforest gets much of its moisture from "cloud drip." These large cloud forests cover Kohala's slopes. This biome is rare. It has a lot of the world's rare and endemic (found nowhere else) species. The soil at Kohala is rich in nitrogen. This helps plant roots grow well.

The happy combination of small trees, bushes, ferns, vines, and other forms of ground cover keep the soil porous and allow the water to percolate more easily into underground channels. The foliage of the trees breaks the force of rain and prevents the impact of soil by raindrops. A considerable portion of the precipitation is let down to the ground slowly by this three-story cover of trees, bushes, and floor plants and in this manner the rain, falling on a well-forested area, is held back and instead of rushing down to the sea rapidly in the form of destructive floods, is fed gradually to the springs and to the underground artesian basins where it is held for use over a much longer interval...

The forest is located across the path of the trade winds. This causes frequent cloud formation and lots of rain. So, the rainforests on Kohala are very important for the island's groundwater supply. People have known for a long time how important Kohala's ecosystem is for water flow.

Before humans arrived, wildlife on Kohala was isolated. It was over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) from the nearest big landmass. Plants and animals arrived by wind, storms, or floating on the ocean. Only about 2,000 successful ancestors made it to Kohala. These then evolved into about 8,500 to 12,500 unique species. This means a very high number of species here are found nowhere else on Earth. Only about 2.5% of the world's rainforests are cloud rainforests. This makes it a truly special habitat.

The mountain supports about 155 native species. These include vertebrates, crustaceans, mollusks, and plants. Many types of fungi, liverwort, and mosses also add to the variety. Up to a quarter of the plants in the forest are mosses and ferns. These plants help capture water from clouds. They also create tiny homes for invertebrates and amphibians.

Kohala is also home to several bogs. These are wet, spongy areas within the cloud forests. Bogs form in low areas where clay in the soil stops water from draining. This water builds up and makes it hard for woody plants to grow. Kohala's bogs have sedges, Sphagnum mosses, and oha wai plants.

The same isolation that created Kohala's unique ecosystem also makes it fragile. Invasive species are a big threat. Alien plants like kahili ginger and strawberry guava push out native species. Before humans settled here, many major organisms like conifers and rodents never reached the island. So, the ecosystem never developed defenses against them. This leaves Hawaii vulnerable to damage from hoofed animals, rodents, and predation.

Kohala's native rainforest has a thick layer of ferns and mosses on the ground. These act like sponges, soaking up rain and sending it to underground aquifers. When feral animals like pigs trample this layer, the forest loses its ability to hold water. Instead of refilling the aquifer, it causes severe loss of topsoil. Much of this soil then washes into the ocean.

Human History on Kohala

There is proof of ancient farming on Kohala's leeward slopes. From 1400 to 1800, the main crop grown here was sweet potato. Farmers also grew yams, taro, bananas, sugarcane, and gourds. Sweet potatoes grow best with 30 to 50 inches (76 to 130 cm) of rain per year. Kohala's rainfall varies a lot. Also, strong winds cause soil erosion. Ancient farmers built earthen banks and stone walls to protect their crops. This technique could reduce wind by 20-30 percent.

Farmers also built stone paths that divided the farmed land. These structures are special because few like them have survived. In the late 1800s, the leeward slopes of Kohala were used for sugarcane plantations. By 1883, steam locomotives were used to move sugarcane from fields to mills and then to boats. Several plantations on the mountain joined to form the Kohala Sugar Company by 1937. At its busiest, the company had 600 employees. It farmed 13,000 acres (53 sq km) of land. It could produce 45,000 tons (99,000,000 lb) of raw sugar each year. The company finally closed in 1975.

Kohala has a very complex water system. In the early 1900s, people built irrigation channels. These channels captured water from higher elevations. They then sent it to the large sugarcane industry. In 1905, the Kohala Ditch was finished. It was a huge network of flumes and ditches, 22 miles (35 km) long. Building it took 18 months and cost 17 lives. Today, ranches, farms, and homes use this ditch. Part of the ditch was a tourist attraction. But it was damaged by the 2006 Kiholo Bay earthquake.

The Hawaii County Department of Water Supply uses streams from Kohala for the island's water. As demand grew, deep wells were added. These wells channel groundwater for homes. In 2003, the Kohala Watershed Partnership was formed. This group of landowners and state managers helps protect the Kohala watershed. They especially work to fight invasive species.

Another project is The Kohala Center. This is a non-profit group for research and education. It was created to offer learning and job chances related to Hawaii's nature and culture. The center's goal is to use the Big Island as a "research and learning laboratory for humanity." The land around Kohala is divided into two districts: North Kohala and South Kohala. The beaches, parks, golf courses, and resorts in South Kohala are known as "the Kohala Coast."

King Kamehameha I, the first King of the unified Hawaiian Islands, was born near Upolu Point. This is the northern tip of Kohala. The site is part of the Kohala Historical Sites State Monument. The original Kamehameha Statue stands in Kapaʻau. Copies are in Honolulu and Washington, D.C..

See also

In Spanish: Kohala para niños

In Spanish: Kohala para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |