Fanny Bullock Workman facts for kids

Fanny Bullock Workman

|

|

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Fanny Bullock |

| Main discipline | Mountaineer |

| Other disciplines | Cartographer, travel writer, explorer |

| Born | January 8, 1859 Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | January 22, 1925 (aged 66) Cannes, France |

| Career | |

| Notable ascents |

|

| Famous partnerships | William Hunter Workman |

| Family | |

| Spouse |

William Hunter Workman

(m. 1882) |

| Children | 2, including Rachel |

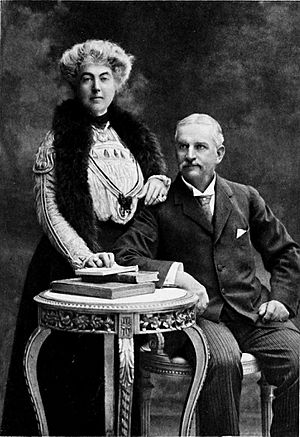

Fanny Bullock Workman (born January 8, 1859 – died January 22, 1925) was an American explorer, writer, and mountaineer. She was especially known for her adventures in the Himalayas. Fanny was one of the first professional female mountaineers. She explored new places and wrote exciting books about her journeys.

Fanny set several women's altitude records for climbing. She wrote eight travel books with her husband, William Hunter Workman. She was also a strong supporter of women's rights and women's suffrage, which meant women's right to vote.

Fanny came from a rich family and went to the best schools for girls. She also traveled a lot in Europe. When she married William Hunter Workman, she gained even more advantages. After learning to climb in New Hampshire, Fanny traveled the world with her husband. They used their wealth to explore Europe, North Africa, and Asia.

The Workmans had two children, but Fanny was not a typical mother for her time. They left their children with schools and nurses. Fanny saw herself as a "New Woman" who could do anything a man could. The Workmans started their travels by cycling through Switzerland, France, Italy, Spain, Algeria, and India. They rode thousands of miles, sleeping wherever they could find shelter. They wrote books about each trip. Fanny often wrote about the lives of women she met. Their early cycling books were more popular than their mountaineering books.

After their cycling trip in India, the couple went to the Western Himalaya and the Karakoram for the summer. There, they discovered high-altitude climbing. They returned to this unexplored region eight times over the next 14 years. Even without modern climbing gear, the Workmans explored many glaciers and climbed several mountains. Fanny eventually reached 23,000 feet (7,000 m) on Pinnacle Peak. This was a new altitude record for women at the time.

They planned long expeditions but sometimes had trouble getting along with local workers. Coming from a wealthy American background, they didn't always understand the local people. This made it hard to find and work with reliable porters, who carried their gear.

After their trips to the Himalaya, the Workmans gave talks about their travels. They were invited to speak at important societies. Fanny Workman became the first American woman to lecture at the Sorbonne in Paris. She was also the second woman to speak at the Royal Geographical Society in London. She received many awards from European climbing and geography groups. Fanny was seen as one of the best climbers of her time. She proved that women could climb at high altitudes just as well as men. She helped break down gender barriers in mountaineering.

Contents

Early Life and First Climbs

Fanny Workman was born on January 8, 1859, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Her family was very rich and well-known. Her father, Alexander H. Bullock, was a businessman and a governor of Massachusetts. Fanny was the youngest of three children. She was taught by private teachers and later went to finishing schools in New York City, Paris, and Dresden.

Even when she was young, Fanny didn't like being limited by her wealthy background. She loved adventure. She wrote stories about brave women who explored mountains. In one story, a girl runs away to Grindelwald and becomes an excellent climber. This story showed Fanny's own love for travel, mountains, and women's rights.

In 1879, Fanny returned to the United States. On June 16, 1882, she married William Hunter Workman. He was 12 years older than her and also from a rich, educated family. They had a daughter, Rachel, in 1884.

William introduced Fanny to climbing after they married. They spent many summers in the White Mountains in New Hampshire. There, Fanny climbed Mount Washington (6,293 feet or 1,918 metres) many times. Climbing in the northeastern United States helped Fanny improve her skills alongside other women. Unlike European clubs, American climbing clubs in the White Mountains allowed women members. They encouraged women to climb. This helped create a new image of American women as both home-loving and athletic. Fanny loved this idea. By 1886, women sometimes outnumbered men on hiking trips in New England. This early experience helped shape Fanny's strong belief in women's rights. She spoke openly about women's rights more than any other famous climber of her time.

Both Fanny and William didn't like living in Worcester. They wanted to live in Europe. After both their fathers died, leaving them a lot of money, the couple took their first big trip to Europe. They toured Scandinavia and Germany.

Moving to Europe and Cycling Adventures

In 1889, the Workman family moved to Germany. William said it was for his health, but he got better very quickly. Their second child, Siegfried, was born in Dresden. Fanny chose not to follow the usual roles of a wife and mother. Instead, she became an author and adventurer. She lived a very active life that was different from what was expected of women in the 1800s.

As a feminist, Fanny believed that women could be equal to or even better than men in tough activities. She showed what the "New Woman" could achieve. The Workmans often left their children with nurses while they went on long trips. In 1893, Siegfried died from illness. After his death, Fanny became even more determined to explore. She saw her bicycle tours as a way to be free from traditional family duties. She could focus on her own interests and goals. They even missed their daughter Rachel's wedding in 1911 because they were exploring in the Karakoram.

Together, the Workmans explored the world. They wrote eight travel books about the people, art, and buildings they saw. They knew their books were important contributions to travel writing. Their mountaineering books didn't say much about the local cultures in remote areas. But they included beautiful descriptions of nature and detailed facts about glaciers for scientists. Fanny and William added scientific details to impress groups like the Royal Geographical Society. Fanny also thought science would make her more respected as a climber. However, this sometimes made their books less popular with general readers. Fanny wrote most of these travel books herself. In them, she often wrote about the difficulties women faced wherever she traveled.

Fanny was a strong supporter of women's rights. She used her travels to show her own abilities and to highlight the unfairness other women lived with. Their books sometimes described the local people as "exotic" or "primitive." But at other times, they showed that the local people saw them in a similar way. This suggests the Workmans were sometimes aware of their own biases.

Between 1888 and 1893, the Workmans took bicycle tours in Switzerland, France, and Italy. In 1891, Fanny became one of the first women to climb Mont Blanc. She was also one of the first women to climb the Jungfrau and the Matterhorn. Her guide for the Matterhorn was Peter Taugwalder, who had been on the first successful climb of that mountain. In 1893, the couple decided to explore beyond Europe. They went to Algeria, Indochina, and India. These longer trips were Fanny's idea.

Their first long tour was a 2,800-mile (4,500 km) bicycle trip across Spain in 1895. Each of them carried 20 pounds (9.1 kg) of luggage. They rode about 45 miles (72 km) a day, sometimes up to 80 miles (130 km). They later wrote Sketches Awheel in Modern Iberia about their trip. In it, they called Spain "rustic, quaint, and charming." In Algerian Memories, Fanny focused on the beauty of the countryside. But she also pointed out how women were treated badly in Algerian society.

Adventures in India

The Workmans' trip to India, Burma, Ceylon, and Java lasted two and a half years. It began in November 1897. They covered 14,000 miles (23,000 km) in total. Fanny was 38 and William was 50 at the time. They bicycled about 4,000 miles (6,400 km) from the very south of India to the Himalaya in the north. To make sure they could get supplies, they rode along main roads near railways. Sometimes, they had to sleep in railway waiting rooms if there was no other place. They carried very few supplies, including tea, sugar, biscuits, cheese, canned meats, water, pillows, blankets, writing materials, and first-aid kits. At the northern end of their trip, they left their bicycles and hiked over mountain passes between 14,000 feet (4,300 m) and 18,000 feet (5,500 m).

The trip was very tough. They often had little food or water. They dealt with many mosquitoes and fixed up to 40 bicycle tire punctures a day. They sometimes slept in places with rats. Fanny Workman's book about the trip focused on the ancient buildings they saw, rather than the local cultures of the time. Mrs. Workman wrote about India, "I have wheeled through much enchanting scenery... But I have never cycled 1200 miles in a country so continuously beautiful." The Workmans knew a lot about India's history for Westerners of their time. They had read important Indian epics before their trip. They wanted to learn about the culture that created these stories. They spent more time learning about ancient history than talking with people living there.

Challenges with Local Helpers

In the summer of 1898, the couple decided to escape the heat. They explored the western Himalaya and Karakoram. They planned to explore the area around Kanchenjunga in Sikkim next. Then, they wanted to travel to the mountains near Bhutan. But they faced many problems, including difficult paperwork and bad weather.

The biggest problems were with hiring local helpers, called porters. They hired 45 porters and bought supplies for mountain travel. But costs went up quickly when people heard about the wealthy Americans. They couldn't leave until October 3, and cold weather was coming. The Workmans often complained in their writings about the porters. They said the porters were hard to work with and refused to walk more than five miles (8.0 km) per day. Three days into their journey, the Workmans reached snow. The porters refused to work in such cold conditions and made everyone return to Darjeeling.

The Workmans always had trouble with porters. They needed local porters to carry their heavy gear because they couldn't carry enough supplies for a multi-month trip themselves. They had to transport tents, sleeping bags, camera equipment, scientific tools, and a lot of food. The porters were often unsure about the whole adventure. Local people rarely climbed mountains and were not used to taking orders from a woman. This made Fanny's job difficult. The Workmans tried to solve these problems by being bossy. Some historians say the Workmans were "victims of their own faults." They were too impatient and didn't try to understand the porters. They were criticized by the British for being uncaring and unskilled in how they treated the Indian people.

Mountaineering in the Himalayas

After their first trip to the Himalaya, the Workmans became fascinated with climbing. Over 14 years, they traveled to the area eight times. At that time, the region was almost completely unexplored and unmapped. Their trips were made without modern lightweight gear, freeze-dried food, sunblock, or radios. On each trip, they explored, surveyed, and took photos. They then wrote reports about what they found and created maps. The couple shared duties. One year, Fanny would plan the trip, and William would work on scientific projects. The next year, they would switch roles.

After their first trip and the porter problems, the Workmans hired Matthias Zurbriggen. He was the best and most experienced mountain climbing guide at the time. So, in 1899, with 50 local porters and Zurbriggen, the Workmans began to explore the Biafo Glacier in the Karakoram. But dangerous crevasses (deep cracks in the ice) and bad weather made them change plans. They went to the Skoro La Glacier and the unclimbed peaks around it instead. They reached Siegfriedhorn, an 18,600-foot (5,700 m) summit that Fanny named after her son. This gave Fanny an altitude record for women at the time.

Next, they camped at 17,000 feet (5,200 m) and climbed a higher peak of 19,450 feet (5,930 m). They named it Mount Bullock Workman. From there, they saw a far-off mountain and realized it was K2, the second-highest mountain in the world. Fanny Workman may have been the first woman recorded to have seen it. Finally, they climbed Koser Gunge (20,997 feet or 6,400 metres). This gave Fanny her third altitude record in a row. It was very challenging. They had to hire new porters, set up a new base camp, and stay overnight at about 18,000 feet (5,500 m). In the morning, they climbed a 1,200 feet (370 m) wall and faced strong winds. During the final climb to the top, Fanny's fingers were so numb she couldn't hold her ice ax. One of the porters left them. Fanny was a "slow, relentless, and intrepid" climber. She was able to climb so high because she was very persistent and didn't get altitude sickness. At the start of the 20th century, she didn't have special equipment like pitons or carabiners.

Fanny Workman quickly published stories about her climbs, like an article in the Scottish Geographical Magazine. She wrote a long book about this trip called In the Ice World of the Himalayas. Fanny tried to include scientific information and experiments. She even said her modified barometer was better than others. But scholars weren't impressed and noted her lack of scientific knowledge. However, popular reviewers enjoyed the book. One reviewer said, "We have no hesitation in saying that Dr. and Mrs. Workman have written one of the most remarkable books of travel of recent years."

In 1902, the Workmans returned to the Himalaya. They became the first Westerners to explore the Chogo Lungma Glacier, starting in Arandu. They hired 80 porters and took four tons of supplies. But their explorations were limited by almost constant snow and a 60-hour storm. In 1903, they hiked to the Hoh Lumba Glacier with guide Cyprien Savoye. They also tried to climb a nearby mountain they called Pyramid Peak (later renamed Spantik). They camped the first night at 16,200 feet (4,900 m) and the second at 18,600 feet (5,700 m). A sick porter made them camp the third night at 19,355 feet (5,899 m) instead of 20,000 feet (6,100 m). They eventually left him behind. They climbed a 22,567-foot (6,878 m) peak, giving Fanny a new altitude record. William and a porter climbed towards the sharp peak that was their goal. But he stopped a few hundred feet from the top. He realized they couldn't get down to a safe height before altitude sickness became a problem.

After returning from their travels, the Workmans gave lectures all over Europe. Fanny lectured in English, German, or French, depending on the audience. At one talk in Lyon, France, 1000 people filled the hall, and 700 were turned away. In 1905, Fanny became the second woman to speak at the Royal Geographical Society. Her talk was even mentioned in The Times newspaper.

The Workmans returned to Kashmir in 1906. They were the first Westerners to explore the Nun Kun mountain group. For this trip, the couple hired six Italian porters from the Alps, 200 local porters, and Savoye returned as their guide. The Workmans spent the night higher than any previous mountaineers. They stayed at 20,278 feet (6,181 m) on top of Z1 on Nun Kun, at what they called "Camp America."

Pinnacle Peak and Altitude Record

From 20,278 feet (6,181 m), at the age of 47 in 1906, Workman climbed up to Pinnacle Peak (22,735 feet or 6,930 metres). This was a smaller peak in the Nun Kun group of the western Himalaya. It was her greatest climbing achievement. The fact that she "climbed the mountain at all, without modern equipment and wearing her large skirts, shows her ability and determination." She set an altitude record for women that would stand until 1934.

Workman strongly defended her Pinnacle Peak altitude record against anyone who claimed to have climbed higher. Especially against Annie Smith Peck. In 1908, Peck claimed a new record with her climb of Peru's Huascarán. She thought it was 23,000 feet (7,000 m). However, she was wrong about the mountain's height and exaggerated distances she couldn't measure. Workman was so competitive that she paid a team of French surveyors $13,000 to measure the mountain's elevation. It was actually 22,205 feet (6,768 m), which confirmed Fanny's record. Fanny was determined to be the best woman climber. She also kept very careful records to prove her achievements.

Hispar and Siachen Glaciers

In 1908, the Workmans returned to the Karakoram. They explored the 38-mile-long (61 km) Hispar Glacier. They went from Gilgit to Nagir over the Hispar pass (17,500 feet or 5,300 metres). Then they went onto the 37-mile-long (60 km) Biafo Glacier to Askole. Their total journey across these glaciers was another record. Fanny became the first woman to travel across any Himalayan glacier of this size. They were the first to explore its many side glaciers. The maps made by their Italian porters helped map the region for the first time. They recorded how high altitude affected the body. They also studied glaciers and ice formations. They took weather measurements, including altitude data.

The Workmans' exploration of the Rose Glacier and the 45-mile-long (72 km) Siachen Glacier in Baltistan in 1911 and 1912 was their most important achievement. This was because it was the widest and longest subpolar glacier in the world. At the time, it was also the least explored and hardest to reach glacier. For two months, the Workmans explored the 45-mile glacier. They climbed several mountains and mapped the area. They spent the entire time above 15,000 feet (4,600 m). The highest point was Indira Col, which they climbed and named. On this trip, one of their Italian guides fell into a crevasse and died. Fanny was lucky to escape. The others were very shaken but decided to continue. Fanny led them across the Sia La pass (18,700 feet or 5,700 metres) near the start of the Siachen Glacier. They went through an area no one had explored before to the Kaberi Glacier. This exploration and the book they wrote about it were among her greatest accomplishments.

As she wrote in her book, Two Summers in the Ice-Wilds of Eastern Karakoram, she organized and led this trip. She wrote that her husband was with her as a photographer and glacier expert, but she was the main leader. At one 21,000-foot (6,400 m) plateau, Fanny held up a "Votes for Women" newspaper. Her husband took a famous picture of her. They had trained Alpine guides and surveyors with them. Their contributions made sure that their map of the Siachen Glacier was accurate and remained useful for many years.

Later Life and Legacy

After their 1908–12 trip, the couple stopped exploring. They focused on writing and lecturing, mainly because World War I started in 1914. Workman became the first American woman to lecture at the Sorbonne in Paris. She was also one of the first women to become a member of the Royal Geographical Society. She earned this honor because her writings included scientific observations about glaciers and other natural features. She also received awards from 10 European geographical societies. She was eventually chosen as a member of the American Alpine Club, Royal Asiatic Society, and other important climbing and exploration groups. She was very proud of these achievements and listed them on the title pages of her books.

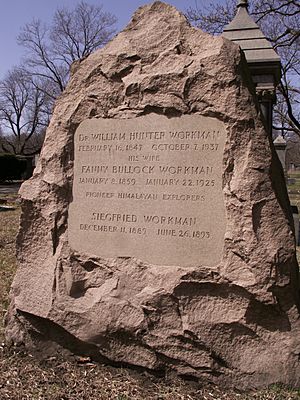

Workman became ill in 1917 and died after a long illness in 1925 in Cannes, France. Her ashes were buried in Massachusetts. They are now with her husband's ashes under a monument in Worcester, Massachusetts' Rural Cemetery. The monument reads "Pioneer Himalayan Explorers." In her will, she left $125,000 to four colleges for women: Radcliffe, Wellesley, Smith, and Bryn Mawr. These gifts showed her lasting interest in helping women advance. They also showed her belief that women were equal to men.

Women in Climbing

Along with Annie Smith Peck, Fanny Workman was known as one of the most famous female climbers in the world in the early 1900s. Their friendly competition showed that women could climb in the most remote and difficult places on Earth. Women had climbed regularly in the Alps since the 1850s. But in the Himalayas, mountaineering was mostly done by wealthy English men. No other women climbed in the Himalaya until after World War I. By then, better equipment and organization had changed the risks and difficulties of expeditions.

Workman was a strong feminist and supported women's suffrage (the right to vote). She wanted her readers to understand how her achievements showed the potential of all women. In her writings, Workman described herself as "questioning or breaking the rules of Victorian female behavior." She proved that women were strong enough to succeed outside the home. She showed how easily she could handle tough physical activities. This included cycling long distances in hot places or climbing mountains in cold temperatures and high altitudes. Workman challenged a world mostly for men. Her obituary in the Alpine Journal hinted at the challenges she faced. It said that some people might have felt it was strange for a woman to enter the world of exploration, which had long been only for men.

However, some experts suggest that gender discrimination was more obvious in everyday life than in high mountains. In high places, like the Himalaya, women climbers could feel more equal and powerful. If they chose, they could be just as sporty or competitive as the men. One writer described Workman as "an aggressive, determined, and uncompromising American traveler" from the turn of the century. She was "one of the first women to work as a professional mountaineer and surveyor." She wrote about her expeditions with her husband to the most remote parts of the Himalaya. She was a strong supporter of women's right to vote. She made it clear that she saw herself as a role model for other women travelers and mountaineers.

Because of the money Workman left in her will, Wellesley College offers a $16,000 fellowship named after Fanny Workman. It helps Wellesley graduates study any subject in graduate school each year. Bryn Mawr also set up a Fanny Bullock Workman Traveling Fellowship. It is given to Ph.D. students in Archaeology or Art History when funds are available.

Exploring the Himalaya

The many books and articles written by the Workmans are "still useful" today, especially for their photos and drawings. However, their maps are "misleading and not always reliable." One evaluation says that while the Workmans were good at describing weather, glaciers, and how high altitudes affected people, they were not good at mapping land features.

The Workmans were among the first climbers to understand that the Himalaya offered the ultimate climbing challenge. Their explorations helped change mountaineering from a tough hobby into a serious, competitive sport. Some historians say that while the Workmans were brave explorers and climbers, they also liked to promote themselves. In their eagerness for fame, they sometimes made their achievements sound more original or important than they were. However, other experts say that the few recent stories about Fanny Workman tend to downplay her achievements. But people at the time thought highly of the Workmans. They were the first Americans to explore the Himalaya in depth. They helped break the British control over Himalayan mountaineering.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Fanny Bullock Workman para niños

In Spanish: Fanny Bullock Workman para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |