Geology of the Falkland Islands facts for kids

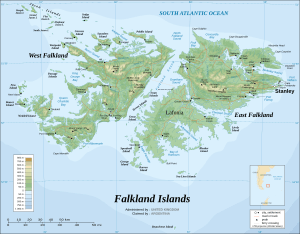

The geology of the Falkland Islands is all about the rocks and landforms that make up these islands. The Falkland Islands sit on a part of the Patagonian continental shelf. Long, long ago, this shelf was part of a huge ancient continent called Gondwana. About 400 million years ago, Gondwana started to break apart. The land that would become the Falkland Islands drifted away from what is now Africa. Scientists have explored the seabed around the islands and found signs of oil. Serious oil exploration began in 1996.

Contents

How the Falkland Islands Formed

Ancient Times: Supercontinents and Ice Ages

The story of the Falkland Islands began over a billion years ago, long before they looked like islands. From the very start, the Falklands have been connected to South America. Rocks deep underground show that the land beneath the Falklands and southern Patagonia formed between 2.1 billion and 1 billion years ago. Since then, these two areas have moved together as one big piece of Earth's crust. They were even next to each other when they were part of an even older supercontinent called Rodinia.

About 290 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period, a huge ice age covered the area. Giant glaciers moved across the land, scraping and carrying rocks. These rocks were left behind as piles of moraines and glacial till. When these glacial sediments turned into stone, they formed the rocks we now call the Fitzroy Tillite Formation in the Falklands. You can find identical rocks in southern Africa, which shows how connected these lands once were.

Breaking Apart: The Mesozoic Era

During the Mesozoic Era, the supercontinent Gondwana broke into many smaller pieces. The piece that held the Falkland Islands first separated from southeastern Africa. This piece then rotated almost 180 degrees! The very old rocks at the center of Gondwana, over a billion years old, can still be found in the Falklands today. These are part of the Cape Meredith complex.

As Gondwana pulled apart, cracks formed in the land. Sand and mud filled these cracks and later hardened into rock. You can see these same rock layers in places like South Africa, western Antarctica, and Brazil. In the Falkland Islands, these layers are known as the West Falkland Group.

About 200 million years ago, powerful forces continued to tear Gondwana apart. Hot, liquid rock called basalt pushed into the cracks between the layers of sediment. When this basalt cooled and hardened, it formed long, wall-like structures called dikes. You can still see these dikes cutting through the oldest rock layers in the southern part of East Falkland and in South Africa.

These powerful forces also created mountains. Part of a mountain chain now forms Wickham Heights on East Falkland. It stretches west through West Falkland into the Jason Islands. A large basin, or dip in the land, also formed and filled with sediments carried by rivers and wind. As these layers of sand and mud hardened, they created the rocks of the Lafonia Group in the Falklands. These rocks are similar to those found in southern Africa's Karoo basin.

Understanding the Falklands' Rocks

The oldest rocks in the Falklands are gneiss and granite from the Cape Meredith complex. Scientists have dated these rocks to be about 1.1 billion years old. You can see them in the cliffs at the southern end of West Falkland. These rocks are like the ancient core of the Gondwana supercontinent. They are very similar to rocks found in South Africa and Antarctica.

On top of these old gneiss and granite rocks are layers of quartzite, sandstone, and shale or mudstone in West Falkland. The way these rocks are layered, with patterns like cross-bedding and ripple marks, shows that they were formed in shallow water, like a river delta. In the Falklands, the ancient currents mostly flowed north. This is very similar to rock formations in South Africa where currents flowed south. This comparison helps prove that the land block containing the islands has rotated over time. Some rocks in central West Falkland even contain fossils of ancient sea creatures that lived in shallow water.

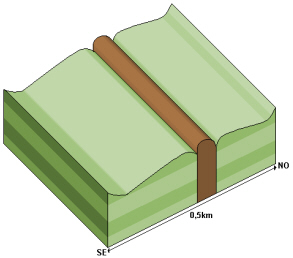

Basalt Dikes and Their Story

The flat area of Lafonia is made of sandy rocks from the Lafonia Group. In some places, vertical basalt dikes cut through these sediments. When the softer surrounding rock wears away, the harder dike is left standing, like on Lively Island. In West Falkland, there are also dikes that cut through the West Falkland Group rocks. However, these dikes are less stable and have eroded away. The only sign they were there are long, straight depressions in the ground. Around these depressions, you can see evidence that the surrounding rock was "baked" by the hot liquid basalt when it pushed through.

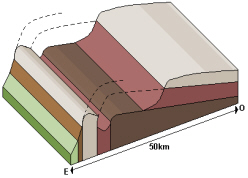

Folding of the Land

Most of the rock layers in West Falkland and its smaller islands are slightly tilted. This tilt varies depending on the type of rock. Harder quartzites, like those at Port Stephens and Stanley, are more resistant than the softer sandy rocks of the Fox Bay Formation. The Hornby Mountains, near Falkland Sound, have been pushed up and folded by powerful forces. Here, the layers of the West Falkland Group, Fitzroy Tillite, and Lafonia Group are tilted almost vertically.

On East Falkland, where the West Falkland Group rocks are found, the layers are very bent and twisted. They are tightly folded with very steep or vertical dips. The soft rocks near the Fox Bay Formation erode easily. But the very hard quartzites are much more resistant. They have created a rugged landscape with steeply tilted rock layers along the mountain chain on East Falkland, stretching from Stanley west to Wickham Heights.

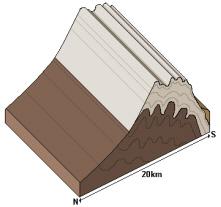

Ice Ages and Weathering

The effects of the last ice age, which happened between 25,000 and 15,000 years ago, are still visible on the islands. The tops of the hills have been exposed to a lot of freezing and thawing. Also, the strong winds in the region carry sand grains. These sand grains act like a sandblaster, eroding rocks most at about one meter above the ground. This unique pattern of erosion can be seen on the higher parts of West Falkland where the quartzites of the Port Stephens Formation are exposed.

During the last glaciation, snow built up year after year and formed glaciers in some sheltered areas. These glaciers changed the landscape on the eastern mountain slopes, which were protected from the strong westerly winds. Glaciers likely formed on the eastern slopes because the climate might have been very dry, or the strong winds prevented them from forming elsewhere.

Another sign of glaciation on East Falkland are the bowl-shaped basins called glacial cirques on Mount Usborne. On West Falkland, there are cirques on Mount Adam and in the Hornby mountains. Several of these cirques now hold small ponds called tarns.

Piles of rock and debris called moraines are also left behind by glaciers. In the Falklands, these are usually found only at the opening of the cirques. However, in one valley, a moraine extends about 3 kilometers from where the ice likely started. These moraines are different from the widespread stone runs, which are formed by different processes related to freezing and thawing.

The large boulders in the stone runs are pieces of quartzite that have been broken down repeatedly by weathering, possibly by a combination of freezing and thawing and changes in temperature. They are found mainly in the Port Stanley Beds and, to a lesser extent, in the Port Stephens Formation. If you dig into a stone run, you'll see that the top parts of the rocks are a different color from the bottom parts. This is because rainwater has whitened the exposed stones, making them light grey. Below ground, where they are protected from erosion, the rocks have an orange color from iron oxide.

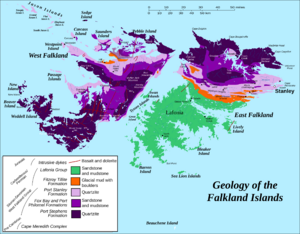

Geological Map of the Falkland Islands

This table shows the different rock layers found in the Falkland Islands, from oldest to newest:

| Age | Formation | What it's made of |

|---|---|---|

| Jurassic | Intrusive dikes | Basalt and dolerite (volcanic rocks) |

| Carboniferous-Permian | Lafonia Group | Sandstone and mudstone |

| Fitzroy Tillite Formation | Glacial mud and boulders | |

| Silurian-Devonian (West Falkland Group) |

Port Stanley Formation | Quartzite (very hard rock) |

| Fox Bay and Port Philomel Formations | Sandstone and mudstone | |

| Port Stephens Formation | Quartzite | |

| Precambrian | Cape Meredith Complex | Gneiss and granite (very old, hard rocks) |

Oil and Gas Exploration

Searching for Oil and Gas Reserves

The area where companies are looking for petroleum (oil and gas) near the Falkland Islands is in the sea north of the islands. It covers a huge area of 400,000 square kilometers and has several rock basins from the Mesozoic era. After using special sound waves to map the underground layers, six test wells were drilled. Five of these wells found samples of petroleum. However, none of them found enough oil to be worth drilling for commercially.

According to studies by geologists, the oil is found about 2,700 meters below the sea. The main rocks that create oil are even deeper, below 3,000 meters. Scientists believe that more than 60 billion barrels of oil might have been created naturally in the North Falkland Basin. This is based on studies of rock samples and assumes a thick layer of oil-producing rock. Even with more careful estimates, a significant amount of oil could exist. For example, in a smaller area, over 11.5 billion barrels of oil could be present.

The brown sediments found in lakes are similar to some of the richest oil-producing rocks in the world, found in the Junggar basin in China. Calculations suggest that the rocks in the North Falkland basin have the second-highest potential for producing oil, after the Junggar basin.

However, even though the wells show that there are rocks that can produce oil, they also show that many of the target rock layers are made of volcanic material. These rocks have low porosity, meaning they don't have many tiny spaces to store large amounts of oil. This is expected because there was a lot of volcanic activity to the west when these sediments were forming.

History of Oil Exploration

Geological surveys of the Falklands began in the late 1970s. Two companies used seismic surveys to map the seafloor around the islands. The data looked promising for drilling, but the island government wasn't ready to give out drilling licenses. At that time, most oil drilling in British waters was happening in the North Sea. Some limited surveys continued, but they stopped completely after the Falklands War in 1982.

In 1992, the Falkland Islands government hired the British Geological Survey to restart geological work. After an initial study showed several promising basins north, south, and east of the islands, the first drilling licenses were given out in 1996. Seven companies agreed to drill. Six test wells were drilled as planned during the first five years.

Along with geological data, environmental information was also collected during the drilling. Investigations into oil reserves in the Falklands have continued, but large-scale oil extraction has not yet started. A new drilling program began in February 2010, and more drilling has happened since then.

How Oil Forms in the North Falkland Basin

Oil exploration has found that the North Falkland Basin has rocks that can create over 102 kilograms of hydrocarbons (oil and gas) per tonne of rock. Even though a large part of this rock layer is not yet fully "mature" (meaning it hasn't produced all the oil it can), it can still generate hydrocarbons below 2,000 meters deep. The rocks that produce the most oil are found at about 3,000 meters deep.

Scientists estimate that the basin could have generated up to 60 billion barrels of oil. Below the main oil-producing rock layer, there is a sandstone layer about 100 meters thick with good porosity (up to 30%). This means it could store oil. However, very few wells have drilled deep enough into this zone to fully explore it.

The lack of high pressure in the basin suggests that any oil produced might have moved sideways. This oil could be trapped in other rock formations deeper down or to the side of the source rock. These deeper rocks, with their low porosity, could act like a seal, keeping the oil trapped unless there are faults (cracks) that cut through them.

See also

In Spanish: Geología de las islas Malvinas para niños

In Spanish: Geología de las islas Malvinas para niños

- Drainage basin

- Depression (geology)

- Geological fold

- Geologic unit

- Lithostratigraphy

- Maturity (geology)

- Paleontology

- Palynology

- Petroleum geology

- reflection seismology

- Sequence stratigraphy

- Sedimentary basin

- Structural basin

- Stone runs