Hugo Grotius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hugo Grotius

|

|

|---|---|

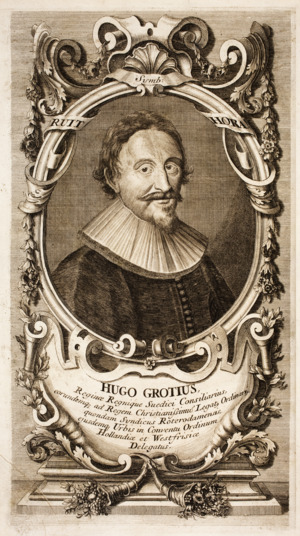

Portrait of Hugo Grotius

by Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, 1631 |

|

| Born | 10 April 1583 |

| Died | 28 August 1645 (aged 62) Rostock, Swedish Pomerania

|

| Alma mater | Leiden University |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Natural law, humanism |

| Academic advisors | Justus Lipsius |

|

Main interests

|

Philosophy of war, international law, political philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Theory of natural rights, grounding just war principles in natural law, governmental theory of atonement |

|

Influences

|

|

Hugo Grotius (born April 10, 1583 – died August 28, 1645) was a very important Dutch thinker. He was a humanist, diplomat, lawyer, and writer. He is famous for helping to create international law. This is the set of rules that countries agree to follow when dealing with each other.

Grotius was a child genius. He started studying at Leiden University when he was only eleven years old. Later, he was put in prison in Loevestein Castle because of his involvement in political arguments in the Dutch Republic. But he managed to escape! He hid inside a chest of books. After his escape, he lived in France for many years, where he wrote some of his most important books.

His ideas about international law, especially about war and peace, are still studied today. He also wrote about the idea of rights, saying that rights belong to people, not just to things.

Contents

Early Life and Amazing Talent

Hugo Grotius was born in Delft, a city in the Netherlands, during a time of war called the Eighty Years' War. His father, Jan Cornets de Groot, was a smart man who loved to learn. He made sure Hugo had a great education from a young age.

Hugo was a true child prodigy. He went to Leiden University when he was just eleven years old! There, he learned from some of the smartest people in Europe. By the time he was 16, he had already published his first book.

In 1598, when he was 15, he went on a special trip to Paris with a Dutch leader named Johan van Oldenbarnevelt. The King of France, Henri IV, was so impressed that he called Grotius "the miracle of Holland." After this, Grotius became a lawyer in The Hague and later the official historian for the Dutch government.

In 1608, he married Maria van Reigersberch. They had seven children together.

Working as a Jurist and Lawyer

The Netherlands was at war with Spain. Even though Portugal was allied with Spain, it wasn't officially at war with the Dutch. In 1603, Grotius's cousin, Captain Jacob van Heemskerck, captured a Portuguese merchant ship called the Santa Catarina near Singapore.

This capture caused a big problem. Some people thought it was wrong to take the ship, and the Portuguese demanded their cargo back. Grotius was asked to write a legal defense for why the Dutch could keep the ship.

His work led to a famous book called Mare Liberum (which means The Free Seas), published in 1609. In this book, Grotius argued that the sea should be open to everyone. He said that all countries should be free to use the seas for trade and travel. This idea was very important for the Dutch, who had a strong navy and wanted to trade all over the world.

However, England, another powerful trading nation, disagreed. They believed that countries could claim parts of the sea as their own. Despite this, Grotius's idea of "freedom of the seas" became very influential and is still important for international waters today.

Life in Paris and Key Works

After his escape from prison, Grotius moved to Paris, France, in 1621. The French king gave him money to live there. He stayed in France for most of the next 23 years.

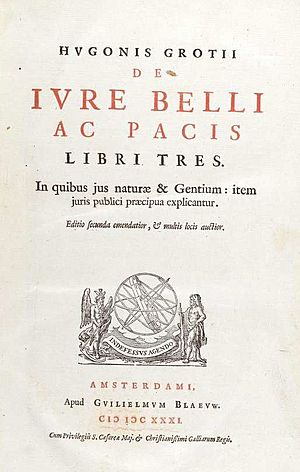

In 1625, while in Paris, Grotius published his most famous book: De jure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace). This book was dedicated to the French King, Louis XIII. It was a huge effort to create rules for how countries should act during wars and how they could achieve peace.

He also wrote a book in Latin called De veritate religionis Christianae (On the Truth of the Christian Religion). He had started writing this as a poem while in prison.

In 1634, the powerful country of Sweden asked Grotius to be their ambassador to France. He accepted and spent ten years in this important role. His job was to help negotiate an end to the Thirty Years' War, a major conflict in Europe. During this time, he also wrote many texts about uniting Christians.

On the Law of War and Peace

Grotius lived during a time of many wars, like the Eighty Years' War and the Thirty Years' War. He was very worried about how much conflict there was between nations and religions. His most important book, De jure belli ac pacis libri tres (On the Law of War and Peace: Three books), tried to set rules for these conflicts.

This book, published in 1625, laid out principles of natural law. These are basic rules that Grotius believed applied to all people and nations, no matter their local customs. The book is divided into three parts:

- Book I: Discusses what war is and when it can be considered fair or "just." He argued that war is only right in certain situations.

- Book II: Identifies three main reasons for a "just war": self-defense, getting back what was wrongly taken, and punishment. He looked at many different situations to see if these reasons applied.

- Book III: Explores the rules that should be followed once a war has started. Grotius famously argued that all sides in a war must follow these rules, even if they believe their cause is right.

Natural Law and Its Impact

Grotius's idea of natural law was very important in the 17th and 18th centuries. He believed that nature was God's creation, so natural law had a religious basis. He thought that moral rules from the Old Testament, like the Ten Commandments, were still valid and helped explain natural law. He said that God's word and natural law could not contradict each other.

His ideas influenced many other thinkers, like John Locke. Through these philosophers, Grotius's thinking helped shape important events like the Glorious Revolution in England and the American Revolution.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1644, Queen Christina of Sweden called Grotius back to Stockholm. He traveled there in difficult winter conditions. In the summer of 1645, he decided to leave Sweden.

On his way back, Grotius was caught in a shipwreck. He washed ashore in Rostock, Germany, very ill. He died on August 28, 1645. His body was brought back to his home country and buried in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft.

Grotius's personal motto was Ruit hora, which means "Time is running away." He is said to have said, "By understanding many things, I have accomplished nothing" as his last words.

His influence faded for a while, but his ideas became popular again in the 20th century, especially after World War I. Today, he is still seen as one of the most important thinkers in the history of international law. He helped create the idea that countries should follow rules and agreements, not just force, when dealing with each other.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hugo Grocio para niños

In Spanish: Hugo Grocio para niños

- Coenraad van Beuningen

- Emer de Vattel

- English school of international relations theory

- International waters

- 9994 Grotius - an asteroid named after Hugo Grotius