Hebron glass facts for kids

Hebron Glass (which in Arabic is called zajaj al-Khalili) is a special type of glass made in Hebron. This city in Palestine has been famous for its glassmaking for a very long time, going all the way back to when the Romans ruled the area. Even today, there's a part of Hebron's Old City called the "Glass-Blower Quarter," and Hebron glass is still a popular thing for tourists to see and buy.

In the past, glassmakers used local materials like sand from nearby villages, a chemical called sodium carbonate (from the Dead Sea), and special powders like iron oxide and copper oxide to add color. But now, they often use recycled glass instead. Making Hebron glass is a family tradition, and the special techniques are kept secret and passed down through generations. Only a few Palestinian families run the glass factories, which are located just outside the city. They make many beautiful things, including glass jewellery like beads, bracelets, and rings. They also create stained glass windows and glass lamps. However, because of the conflict in the region, it has become harder to make and sell Hebron glass.

Contents

A Look Back: The History of Hebron Glass

The art of making glass in Hebron started during the time of the Romans in Palestine, between 63 BCE and 330 CE. Back then, the ancient Phoenician glass industry, which was along the coast, began to shrink. So, the glassmaking skills moved inland, especially to Hebron. We know this because glass items from Hebron, dating back to the 1st and 2nd centuries, have been found and are now in museums.

Glass in Famous Buildings

Hebron glass was used in important buildings. For example, stained glass windows made in Hebron in the 12th century can be seen in the building over the Cave of the Patriarchs, which was a church during the Crusader times. Another famous example is the stained glass windows that decorate the Dome of the Rock in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Many Christian travelers who visited Hebron in the Middle Ages wrote about its glassmaking. Between 1345 and 1350, a monk named Niccolò da Poggibonsi said that "they make great works of art in glass." Later, in the late 1400s, a German friar named Felix Faber visited Hebron. He described walking through a street where many different craftspeople worked, but especially glassmakers. He noted that they made glass that wasn't clear, but "black, and of the colors between dark and light."

Some experts believe that the way Hebron glass is made today probably started around the 13th century CE. This matches what visitors like Felix Fabri saw. Other ideas suggest that the techniques might have come from the Venetian glass tradition, or that they were already in Hebron during the Crusades and were even taken back to Europe from there, possibly originally from Syria.

What Was Made and Where It Went

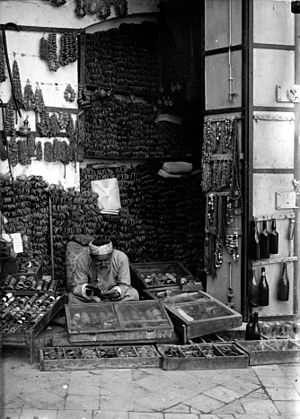

The glass factories in Hebron mostly made useful items. These included cups and plates for eating and drinking, and lamps that used olive oil or later, petrol. But they also made jewellery and accessories. Bedouins from places like the Negev desert and Sinai were the main buyers of the jewelry.

However, many expensive Hebron glass items were also sent far away. They traveled by camel caravans with guards to Egypt, Syria, and Transjordan. By the 16th century, there were special places in al-Karak (Jordan) and Cairo (Egypt) just for selling Hebron glass.

Hebron Glass in Recent Centuries

The glass industry was a major employer and brought a lot of money to its owners. It was well-known throughout the Arab world. Travelers from Western countries in the 18th and 19th centuries also wrote about Hebron's glass industry. For example, Volney wrote in the 1780s that they made "great quantity of coloured rings, bracelets... and a variety of other trinkets, which are sent even to Constantinople."

In the early 1800s, Ulrich Jasper Seetzen noted that about 150 people worked in the glass industry in Hebron. Later, in 1844, Robert Sears mentioned that Hebron's people made glass lamps that were sent to Egypt.

Later in the 19th century, the production of Hebron glass decreased. This was because of competition from cheaper glass products imported from Europe. Still, Hebron glass items continued to be sold, especially to poorer people, often by traveling Jewish traders from the city. Hebron glass ornaments were even shown at the World Fair of 1873 in Vienna. A French report from 1886 said that glassmaking was still an important way for Hebron to earn money, with four factories making a lot of money each year.

Today, glassblowing continues in three factories. These are located outside the old part of the city, between Hebron and the nearby town of Halhul. They mostly make useful household items and souvenirs. Two of these factories are owned by the Natsheh family. Their products are displayed in large halls near the factories.

Hebron glass attracts both local and international tourists. However, due to ongoing problems with exporting goods, fewer tourists, and limits on Palestinian freedom of movement after the Second Intifada, the industry has faced difficulties. Some experts, like Nazmi al-Ju'bah, believe the future of the Hebron glass industry is uncertain under these conditions.

How Hebron Glass is Made

Hebron glass was traditionally made using sand from the village of Bani Na'im, which is east of Hebron. They also used sodium carbonate from the Dead Sea. But today, the main material used to make Hebron glass is recycled glass.

The exact way Hebron glass is made is a secret. Only a few Palestinian families who run the factories know the full process. They pass these skills down through generations by teaching their children as apprentices. One master glassmaker said, "You can learn to play the 'oud (a musical instrument) at any age, but unless you begin [glasswork] as a child, you will never become a master."

The glassblowing technique used is very old. Molten (melted) glass is taken out of a hot furnace on the end of a long iron pipe. The glassblower then blows into the pipe, and a metal tool called a kammasha is used to shape the glass. The glass is put back into the furnace to be heated again and reshaped. Finally, it's taken off the pipe and placed in a cooling room to harden slowly.

Hebron Glass Jewellery

Glass beads for jewellery have been made in Hebron for a long time. Blue beads and glass beads with 'eyes' (called owayneh) were made to be used as amulets. People believed these were especially good at protecting against the evil eye, which is a belief that someone can cause harm with a jealous look.

In the collections of the British Museum, there are several glass necklaces that were made in Hebron during the Mandate period or even earlier. Besides necklaces made of blue and green beads, and 'eyes' beads, there are also beads shaped like small hands, called a Hamsa. This represents the hand of Fatimah, the daughter of the prophet Muhammad. Most of a woman's jewellery was given to her when she got married. In the early 1920s, in a village called Bayt Dajan, a glass bracelet (ghwayshat) made in Hebron was considered a necessary part of a bride's trousseau (the special clothes and items a bride brings to her marriage).

Hebron Trade Beads

In 1799, an English traveler named William George Browne wrote about the making of "Coarse glass beads...called Hersh and Munjir" in Palestine. The "Munjir" (or Mongur) were large beads, while the Hersh (or Harish) were smaller. These Hebron glass beads were used for trade, especially exported to Africa from the early to mid-19th century.

These beads spread throughout West Africa. In Kano, Nigeria, they were sometimes ground down on the edges to make the round beads fit together better on a string. Because of this, they became known as "Kano Beads," even though they were not originally made in Kano. By the 1930s, their value had gone down. In 1937, a person named A. J. Arkell wrote that Sudanese women were selling the beads "for a song" to Hausa traders in Darfur.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Vidrio de Hebrón para niños

In Spanish: Vidrio de Hebrón para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |