Henry Cavendish facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Cavendish

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 10 October 1731 |

| Died | 24 February 1810 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Peterhouse, Cambridge |

| Known for | Discovery of hydrogen Measuring the Earth's density (Cavendish experiment) |

| Awards | Copley medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry, physics |

| Institutions | Royal Institution |

Henry Cavendish (born 10 October 1731 – died 24 February 1810) was an important English scientist. He was a brilliant chemist and physicist who did many experiments and developed new ideas.

Cavendish is famous for discovering hydrogen gas, which he called "inflammable air." He also figured out that this "inflammable air" combined with another gas to form water. Later, another scientist, Antoine Lavoisier, gave hydrogen its modern name.

He was a very shy person but known for being super accurate in his work. He studied things like the air we breathe, different gases, how water is made, and the rules of electricity. He also calculated the density (how heavy something is for its size) and mass (how much "stuff" is in something) of the Earth. His famous experiment to measure the Earth's density is now called the Cavendish experiment.

Contents

Early Life and Science Journey

Henry Cavendish was born in Nice on October 10, 1731. His family was living there at the time. His mother, Lady Anne de Grey, passed away when Henry was almost two years old. His father, Lord Charles Cavendish, raised Henry and his younger brother.

From age 11, Henry went to a private school near London. When he was 18, he started studying at the University of Cambridge. He left after three years without getting a degree, which was common back then. After that, he lived with his father in London and soon had his own laboratory.

Henry's father was also interested in science and was part of the Royal Society in London. In 1758, he started taking Henry to meetings and dinners there. By 1760, Henry became a member himself and attended regularly. He didn't get involved in politics like his father, but he loved science. He was very active in the Royal Society's council.

Because he was so good with scientific tools, he helped check the instruments used for weather and at the Royal Greenwich Observatory. His first important paper, called Factitious Airs, came out in 1766. He also helped with other big science projects, like observing the transit of Venus (when Venus passes in front of the Sun). In 1773, he became a trustee of the British Museum and spent a lot of time there. Later, he joined the Royal Institution and helped with experiments in its lab.

Chemistry Discoveries

Around the time his father passed away, Cavendish started working closely with Charles Blagden. This partnership helped Blagden in the science world, and Blagden helped keep other people from bothering the shy Cavendish. Cavendish didn't publish many books or papers, but he achieved a lot. Many of his ideas about mechanics, optics, and magnetism were found in his notes later.

Cavendish was one of the "pneumatic chemists," who studied gases. He found that a special, very flammable gas, which he called "Inflammable Air," was made when certain acids reacted with certain metals. This gas was hydrogen. Cavendish correctly guessed that water was made of two parts hydrogen.

Even though others had made hydrogen gas before, Cavendish is usually given credit for realizing it was a basic element. In 1777, he discovered that air breathed out by animals turns into "fixed air" (carbon dioxide). He also made carbon dioxide by mixing alkalis with acids. He collected these gases and measured how much they dissolved in water and how heavy they were. He also checked if they could burn. For his work, he received the Royal Society's Copley Medal.

In 1783, Cavendish wrote about measuring the "goodness" of gases for breathing. He invented a new tool, a eudiometer, which gave the best results of its time. He also showed that pure water could be made by burning hydrogen in "dephlogisticated air" (which we now know is oxygen). Cavendish thought that burning hydrogen caused water to form from the air. Some scientists believed hydrogen was a substance called "phlogiston."

In 1785, Cavendish studied the air we breathe. He got very accurate results. He mixed hydrogen and ordinary air in specific amounts and then exploded them with an electric spark. He also did an experiment where he removed both oxygen and nitrogen from an air sample. He noticed a tiny bubble of gas was left over, about 1/120th of the original nitrogen volume. He concluded that "common air consists of one part of dephlogisticated air [oxygen], mixed with four of phlogisticated [nitrogen]."

About 100 years later, two British physicists, William Ramsay and Lord Rayleigh, discovered a new gas called argon. They realized that this inert gas was the "problematic residue" Cavendish had found. Cavendish hadn't made a mistake; he was just incredibly precise! He used very accurate tools and methods, repeated his experiments, and accounted for any errors. The balance he used was one of the most precise of its time.

Cavendish used the older "phlogiston theory" in chemistry for a while. But in 1787, he was one of the first scientists outside France to switch to Antoine Lavoisier's new "antiphlogistic theory," which is closer to modern chemistry. Cavendish also had his own ideas about heat. He believed heat was caused by the movement of tiny particles. He even developed a theory of heat that included the idea of conservation of energy, long before it was officially named.

Measuring the Earth's Density

After his father died, Henry bought a new house in London and another house in Clapham Common, south of London. He kept most of his books in the London house. But he kept most of his scientific tools and did most of his experiments at Clapham Common.

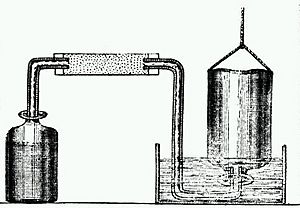

His most famous experiment, published in 1798, was to figure out the density of the Earth. This is now known as the Cavendish experiment. The equipment he used was a special balance called a torsion balance. It was designed by another scientist, John Michell, who died before he could use it. The equipment was sent to Cavendish, who finished the experiment in 1797–1798 and shared his results.

The machine had two small lead balls (about 1.6 pounds each) hanging from a bar. There were also two much larger, stationary lead balls (350 pounds). Cavendish wanted to measure the tiny force of gravitational attraction between them. He made sure the equipment was in a separate room with outside controls and telescopes. This way, he could make observations without disturbing the delicate setup with temperature changes or air currents.

Using this setup, Cavendish measured how much the balance twisted due to the attraction between the balls. From this, he calculated the Earth's density. He found that the Earth's average density is 5.48 times greater than water. This result is very close to what scientists believe today, being within 1 percent of the accepted number!

Cavendish's work helped other scientists find accurate values for the gravitational constant (a number used in gravity calculations) and the Earth's total mass. While his experiment is often described as measuring G or the Earth's mass, Cavendish's main goal was to find the Earth's density.

Electrical Studies

Cavendish's experiments with electricity and chemistry began when he lived with his father. Like his ideas about heat, Cavendish's detailed theory of electricity used math and was based on very precise experiments. He even worked with a colleague, Timothy Lane, to create an artificial "torpedo fish" that could give electric shocks. This showed that the shocks from real torpedo fish were caused by electricity.

He published some of his ideas about electricity in 1771. He showed that if electric force followed a certain rule (getting weaker the further away you are), then extra electric charge would sit on the outside surface of an electrified ball. He proved this with experiments. Cavendish kept working on electricity, but he didn't publish much more about it.

Most of Cavendish's electrical experiments weren't known until about a century later. In 1879, James Clerk Maxwell looked through Cavendish's notes and published them. Many of Cavendish's discoveries were later credited to other scientists because he hadn't published them himself. These included ideas like electric potential (which he called "degree of electrification"), an early unit for capacitance (how much charge something can hold), and the relationship between electric potential and current (now known as Ohm's law). He also discovered rules for how current divides in parallel circuits and the inverse square law of electric force (now called Coulomb's law).

Later Life and Legacy

Cavendish passed away in Clapham on February 24, 1810. He was one of the wealthiest men in Britain at the time. He was buried in the church that is now Derby Cathedral. A road in Derby is named after him.

Cavendish was a very shy person who didn't like being around many people. He preferred to speak to only one person at a time, and only if he knew them and they were male. He didn't talk much, always wore old-fashioned clothes, and didn't seem to have many close friends outside his family. He was seen as quite unusual. He even communicated with his female servants using notes! Some stories say he had a special back staircase built in his house just to avoid seeing his housekeeper, because he was especially shy around women.

His main social activity was the Royal Society Club, where members ate dinner before weekly meetings. Cavendish rarely missed these meetings, and other scientists respected him greatly. However, his shyness meant that if someone tried to talk to him, they might get a quiet reply or just see him quickly leave to find a quieter spot.

Because he was so private and didn't publish much of his work, many of his amazing discoveries were not known until long after his death. In the late 1800s, James Clerk Maxwell went through Cavendish's papers and found many observations and results that others had later been given credit for. These included ideas like Ohm's law and Charles's Law of gases. He also had a detailed "mechanical theory of heat" that was only fully understood in the 21st century.

Cavendish did his famous Earth density experiment in a small building in the garden of his Clapham Common home. His neighbors would point out the building and tell their children that it was "where the world was weighed." To honor Henry Cavendish's achievements, and thanks to money given by his relative, William Cavendish, the University of Cambridge's physics laboratory was named the Cavendish Laboratory by James Clerk Maxwell.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Henry Cavendish para niños

In Spanish: Henry Cavendish para niños

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |