History of Belize (1506–1862) facts for kids

Belize is a country on the east coast of Central America, located southeast of Mexico. Long ago, it was home to indigenous peoples who bravely fought against the Spanish to protect their way of life and culture.

Contents

Ancient Maya and the Arrival of Europeans

The amazing Maya were living in Belize when Europeans first arrived in the 1500s and 1600s. We know from old records and archaeological digs that several Maya groups lived in the area we now call Belize.

The borders of Maya lands back then were different from today's country lines. Some Maya provinces stretched across what is now Belize, Mexico, and Guatemala. For example, the Maya province of Chetumal covered northern Belize and southern Mexico. In the south, near Guatemala, lived the Mopan Maya and the Manche groups. Central Belize was home to the province of Dzuluinicob, which meant "land of foreigners." Its main town was Tipu, located near modern Benque Viejo del Carmen.

In the early 1500s, Spanish explorers like Juan De Solís sailed along the coast of Belize. Later, Hernán Cortés conquered Mexico in 1519. Spain quickly sent expeditions to nearby countries, and the Spanish began conquering Yucatán in 1527.

When Cortés traveled through southwestern Belize in 1525, he found Manche Maya settlements. Later, in the 1600s, the Spanish forced these Maya to move to the Guatemalan Highlands. The Spanish also faced strong resistance from the Maya in Chetumal and Dzuluinicob. Many Maya fled to Belize to escape the Spanish. However, they brought diseases like smallpox and yellow fever with them, which, along with malaria, sadly wiped out many native people.

In the 1600s, Spanish missionaries from Yucatán traveled up the New River. They built churches in Maya towns like Tipu, hoping to convert and control the people. Tipu was an important Maya site for a very long time, even during the Spanish conquest, until 1707.

Even though the Spanish conquered Tipu in 1544, it was too far from their main centers to control easily. Thousands of Maya fled from Yucatán to the south in the late 1500s. The people of Tipu rebelled against Spanish rule. Tipu was important because it was close to the Itzá people in Guatemala. In 1618 and 1619, two Franciscans built a church in Tipu to convert the Maya. But by 1638, Tipu began resisting Spain again. By 1642, the entire Dzuluinicob province was in rebellion. Many Maya towns were abandoned, and about 300 families moved to Tipu, making it the center of the rebellion. By the 1640s, Tipu had over 1,000 people.

During this time, pirates became common along the coast. In 1642 and 1648, pirates attacked Salamanca de Bacalar, the Spanish government's base in southern Yucatán. This led to Spain losing control over the Maya provinces of Chetumal and Dzuluinicob.

From 1638 to 1695, the Maya around Tipu were free from Spanish rule. But in 1696, Spanish soldiers used Tipu to control the area and support missionaries. In 1697, the Spanish conquered the Itzá. In 1707, they forced the people of Tipu to move near Lago Petén Itzá. This was when British settlers became more interested in the area.

Spain and Britain Fight for Control

In the 1500s and 1600s, Spain tried to control all trade and settlements in its New World colonies. But other European powers like the Dutch, English, and French wanted a piece of the action. They used smuggling, piracy, and war to challenge Spain. In the early 1600s, these countries moved into areas where Spain was weak, like small islands and uncharted coasts. Later, England took Jamaica in 1655. This island became a base to support English settlements along the Caribbean coast.

In the early 1600s, on the coast of Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula, English buccaneers (pirates) started cutting logwood. This wood was used to make a dye for the wool industry. Legend says that a buccaneer named Peter Wallace, or "Ballis," settled near the Belize River around 1638, giving the river its name. (However, some believe the name comes from the Maya word belix, meaning muddy-watered.) English buccaneers also used the tricky coastline to attack Spanish ships. Some of these buccaneers might have been refugees from Spanish attacks on other islands. By the 1650s and 1660s, buccaneers stopped attacking Spanish logwood ships and started cutting their own wood. Logwood became the main reason for English settlement for over a century.

A treaty in 1667, where European powers agreed to stop piracy, encouraged buccaneers to become logwood cutters and settle down. The 1670 Godolphin Treaty between Spain and England confirmed England's control over lands and islands it already held in the Western Hemisphere. But the treaty didn't name specific places, so ownership of the coast between Yucatán and Nicaragua was still unclear. Conflicts continued between Britain and Spain over Britain's right to cut logwood and settle. In 1717, Spain kicked British logwood cutters out of the Bay of Campeche. This made the growing British settlement near the Belize River even more important.

The first British settlers lived a rough life. Captain Nathaniel Uring, who was shipwrecked there in 1720, said the British were "a rude drunken Crew, some of which have been Pirates." He found it hard to live among them, hearing "little else to be heard but Blasphemy, Cursing and Swearing."

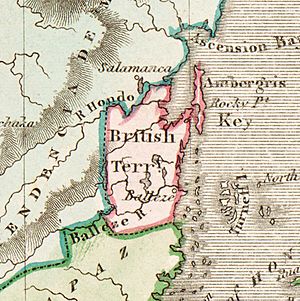

During the 1700s, Spain attacked the British settlers many times. In 1717, 1730, 1754, and 1779, the Spanish forced the British to leave. However, the Spanish never settled the area themselves, and the British always returned to expand their trade. After the Seven Years' War in 1763, the Treaty of Paris allowed Britain to cut and export logwood but said Spain still owned the land. There was no clear agreement on where the logwood cutters could work. The Spanish town of Bacalar in Yucatán, rebuilt in 1730, became a base for attacks against the British. When war broke out again in 1779, the Spanish attacked the British settlement, which was abandoned. The Treaty of Versailles in 1783 again allowed the British to cut logwood between the Hondo and Belize rivers. By then, the logwood trade had slowed down, and mahogany became the main export. So, the settlers asked for a new agreement.

Early Self-Government and Powerful Landowners

The British government didn't want to set up a formal government in the settlement. They feared it would anger Spain. But the settlers, on their own, started holding yearly elections for magistrates to create their own common law rules as early as 1738. In 1765, Admiral Sir William Burnaby from Jamaica visited the settlement. He wrote down and expanded their rules into a document called Burnaby's Code. When settlers returned in 1784, the governor of Jamaica appointed Colonel Edward Marcus Despard as superintendent to oversee the settlement.

The Convention of London, signed in 1786, allowed British settlers, called Baymen, to cut and export logwood and mahogany. This area stretched from the Hondo River in the north to the Sibun River in the south. However, the convention did not allow the Baymen to build forts, create any form of government, or start large farms (plantations). Spain still owned the area and could inspect the settlement twice a year.

The Convention also required Britain to leave its settlement on the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua. Over 2,000 settlers and their slaves from there arrived in Belize in 1787. This greatly increased the British presence. The new settlers often disagreed with the older settlers about land rights and social status.

The last Spanish attack on the British settlement happened in 1798, during the Battle of St. George's Caye. Field Marshal Arturo O'Neill, the Spanish governor of Yucatán, led about thirty ships and 2,500 men. They attacked the British colonists. After several small fights and a two-and-a-half-hour battle on September 10, the British pushed the Spanish away. This was Spain's last attempt to control the territory or remove the British.

Even though treaties banned local government and large farms, both activities grew. By the late 1700s, a small group of wealthy settlers controlled the economy and politics. These settlers claimed about four-fifths of the land allowed by the Convention of London. They did this through rules called location laws, which they passed in the Public Meeting, their first legislature. These same wealthy men also owned about half of all the slaves in the settlement. They controlled trade, taxes, and businesses. A group of magistrates, chosen from among themselves, handled both executive and judicial duties, even though executive actions were forbidden.

The powerful landowners didn't like anyone challenging their control. Colonel Edward Marcus Despard, the first superintendent, was suspended in 1789 because the wealthy cutters challenged his authority. When Superintendent George Arthur tried to break the "monopoly" of the rich cutters in 1816, he only partly succeeded. He declared that all unclaimed land now belonged to the crown, but he still allowed the existing landowners to keep their large holdings.

Slavery in Belize, 1724–1825

Even though cutting logwood was a small operation, settlers brought in slaves to help. Slavery in Belize was mainly for cutting timber, first logwood and then mahogany, because treaties didn't allow large plantations. This meant slavery here was different from other places. The first mention of African slaves in Belize was in 1724. A Spanish missionary said the British had recently brought them from Jamaica and Bermuda. In the late 1700s, about 3,000 slaves lived in Belize, making up three-quarters of the total population. Most slaves were born in Africa, likely from areas like the Bight of Biafra, the Congo, and Angola. The Eboe (Ibo) people were very common; one part of Belize Town was even called Eboe Town. At first, many slaves kept their African traditions. But slowly, a new Creole culture began to form.

White settlers were a minority, but they held all the power and wealth. They controlled the main economic activities like trade and timber. They also controlled the government and legal system. This meant British settlers had a big influence on the development of Creole culture. Missionaries from the Anglican, Baptist, and Methodist churches also helped to reduce and suppress African cultural heritage.

Cutting timber was seasonal work. Workers had to spend months in temporary camps in the forest, away from their families in Belize Town. For logwood, settlers only needed one or two slaves. But when the trade shifted to mahogany in the late 1700s, settlers needed more money, land, and slaves for bigger operations. After 1770, about 80 percent of all male slaves over ten years old cut timber. Huntsmen found the trees. Then, axmen cut them down while standing on platforms high off the ground. Other slaves cared for the oxen that pulled the huge logs to the river. During the rainy season, settlers and slaves floated rafts of logs downriver to be prepared for shipment. Huntsmen and axmen were highly skilled and valued slaves. Because small groups of slaves worked together, there was less need for close supervision. Unlike other plantations, there were no whip-wielding drivers in Belize.

Domestic slaves, mostly women and children, cleaned houses, sewed, washed clothes, cooked, and raised children. Some slaves grew food to sell or to help their owners save money on imported food. Other slaves worked as sailors, blacksmiths, nurses, and bakers. However, few slaves had highly skilled jobs. Young people often started by serving their masters, learning to obey. Then, most young women continued in domestic work, while young men became woodcutters. This limited their opportunities after slavery ended in 1838.

Life for slaves, though different from plantations elsewhere, was still very hard. A report in 1820 spoke of "extreme inhumanity" against them. The settlement's chaplain reported "many instances, of horrible barbarity." Slaves in small, scattered groups could escape more easily if they were willing to leave their families. In the 1700s, many escaped to Yucatán. In the early 1800s, many ran away to Guatemala and Honduras. Some runaways formed communities, like one near the Sibun River, which offered safety to others. When freedom could be found by running into the bush, revolt was not always the first choice. Still, there were many slave revolts. The last one in 1820 was led by two black slaves, Will and Sharper. They had been treated very harshly by their owner and "certainly had good grounds for complaint."

The small group of white settlers kept control by dividing the slaves from the growing population of free Creole people. Free Creoles had some privileges but couldn't be military officers, jurors, or magistrates. Their economic activities were also limited. They could only vote if they owned more property and had lived in the area longer than white people. Despite this, many free black people showed loyalty to British ways. When other British colonies started giving free black people more rights, the Colonial Office threatened to dissolve the Baymen's Public Meeting unless they did the same. So, on July 5, 1831, "Coloured Subjects of Free Condition" were given civil rights, a few years before slavery was fully abolished.

By the time slavery ended in 1838, society was very structured by race and class. The act to abolish slavery in British colonies, passed in 1833, aimed to avoid big social changes. It created a five-year transition period. The act also gave slave owners two benefits: a system of "apprenticeship" where former slaves had to work for their masters without pay, and money for the former slave owners for their "loss of property." These measures made sure that most people, even after being legally freed in 1838, still depended on their former owners for work. These owners still controlled all the land. Before 1838, a few rich people controlled the settlement and owned most of the people. After 1838, this small group of powerful people continued to control the country for over a century. They did this by limiting access to land and by making freed slaves dependent on them through wage advances and company stores.

The Garifuna People Arrive

A new group of people, the Garifuna, arrived in the early 1800s, just as the settlement was dealing with the end of slavery. The Garifuna are descendants of Carib peoples and Africans who had escaped slavery. They had fought against British and French rule in the Lesser Antilles until the British defeated them in 1796. After putting down a rebellion on Saint Vincent, the British moved between 1,700 and 5,000 Garifuna across the Caribbean to the Bay Islands (now Islas de la Bahía) off Honduras. From there, they moved to the coasts of Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and southern Belize. By 1802, about 150 Garifuna had settled in the Stann Creek area (now Dangriga) and were fishing and farming.

More Garifuna came to Belize after being on the losing side of a civil war in Honduras in 1832. Many Garifuna men soon found work cutting mahogany alongside slaves. By 1841, Dangriga, the largest Garifuna settlement, was a busy village. The American traveler John Stephens described the Garifuna village of Punta Gorda as having 500 people and growing many different fruits and vegetables.

The British treated the Garifuna as if they didn't own the land they lived on. In 1857, the British told the Garifuna they had to get leases from the crown or risk losing their homes and lands. The 1872 Crown Lands Ordinance created special areas called reservations for the Garifuna and the Maya. The British stopped both groups from owning land and saw them only as a source of cheap labor.

Changes in Government, 1850–1862

In the 1850s, the superintendent and the wealthy landowners fought for power. At the same time, international agreements led to big changes in Belize's government. In the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850, Britain and the United States agreed to help build a canal across Central America. They also agreed not to colonize any part of Central America. The British thought this only applied to new colonies. But the United States, especially after President Franklin Pierce took office in 1853, argued that Britain had to leave the area, based on the Monroe Doctrine. Britain gave up its claims to the Bay Islands and the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua. But in 1854, Britain created a formal constitution and a legislature for its settlement in Belize.

The Legislative Assembly of 1854 was supposed to have eighteen elected members. Each member had to own property worth at least £400. The assembly also had three official members appointed by the superintendent. Voters also had to own property or earn a certain salary, which meant only wealthy people could vote. The superintendent could delay or dissolve the assembly, propose laws, and approve or reject bills. This meant the legislature was more for discussion than for making real decisions. The Colonial Office in London became the real power. This shift was made stronger in 1862 when the Settlement of Belize in the Bay of Honduras was officially declared a British colony called British Honduras. The crown's representative was then called a lieutenant governor, who reported to the governor of Jamaica.

See also

In Spanish: La Baliza (Nueva España) para niños

In Spanish: La Baliza (Nueva España) para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |