History of Fairbanks, Alaska facts for kids

Fairbanks, the second-largest city in Alaska, began as a trading post on August 26, 1901. A man named E.T. Barnette set up this post on the south bank of the Chena River. Even though people had lived in this area since the last ice age, a permanent town didn't start until the early 1900s.

When gold was found near Barnette's trading post, his temporary stop became a permanent settlement. Many miners rushed to the area, and buildings quickly appeared around his post. In November 1903, the people living there voted to officially create the city of Fairbanks. Barnette became the first mayor, and the city grew fast as thousands arrived during the Fairbanks Gold Rush to search for gold.

By the time of World War I, most of the easy-to-reach gold was gone. Fairbanks' population dropped as miners moved to new gold finds. But then, the Alaska Railroad was built, bringing in heavy equipment. This helped miners dig for more gold. Huge gold dredges were built north of Fairbanks, and the city grew in the 1930s as gold prices went up during the Great Depression. Another big boost came in the 1940s and 1950s. Fairbanks became a key spot for building military bases during World War II and the early years of the Cold War.

In 1968, a huge oil field was found at Prudhoe Bay Oil Field in northern Alaska. Fairbanks became a supply center for this oil field and for building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. This brought a boom to the city, bigger than anything since its founding. It also helped Fairbanks recover from the terrible 1967 Fairbanks Flood. Fairbanks became a government hub in the late 1960s with the creation of the Fairbanks North Star Borough, with Fairbanks as its main city. A drop in oil prices in the 1980s caused a tough time for Fairbanks. But the city slowly got better as oil prices rose in the 1990s. Tourism also became very important for Fairbanks' economy, and both tourism and the city continue to grow, even as oil production slows down.

Contents

Fairbanks Before the City

Even though there wasn't a permanent Native village where Fairbanks is now, Athabascan Indians used this area for thousands of years. Scientists found an old Native camp at the University of Alaska Fairbanks that is about 3,500 years old. From what they found, experts believe Native people used the area for hunting and fishing during different seasons. Also, even older sites, about 10,000 years old, were found at nearby Fort Wainwright. Arrowheads found at the university site matched ones from Asia. This helped show that early humans came to North America across a land bridge.

The first recorded trip into the Tanana Valley and along the Tanana River didn't happen until 1885. But historians think Russian and Hudson's Bay Company traders explored the lower parts of the Tanana and possibly the Chena River in the mid-1800s. In 1885, Henry Tureman Allen from the U.S. Army led the first recorded trip down the Tanana River. He mapped the mouth of the Chena River along the way.

In July 1897, news of the Klondike gold strike reached Seattle, Washington. This started the famous Klondike Gold Rush. Thousands of people boarded steamships to head north to the goldfields. Some travelers sailed around Alaska and up the Yukon River to Dawson City. This was easier than the hard overland journey.

One of these adventurers was E.T. Barnette. He planned to open a trading post at Tanacross, Alaska. This was where the Valdez-Eagle Trail crossed the Tanana River. He hired a steamboat called the Lavelle Young to carry him and his supplies. They started their trip upriver in August 1901. After turning into the Tanana from the Yukon, the steamboat ran into shallow water. After going upstream about 15 miles (24 km) into the Chena River, the boat got stuck again. The captain didn't want to go back downstream with a heavy load. So, he unloaded Barnette's cargo on August 26, 1901. Barnette was not happy about it.

Barnette started building a cabin at a spot he called "Chenoa City." He sold supplies to two prospectors, Felix Pedro and Tom Gilmore, who were in the area. Barnette traded for furs. Then he traveled to Valdez by dog team with his wife and three other men. The mountain pass they used was later named Isabel Pass after Barnette's wife. From Valdez, he went to St. Michael. There, he built another steamboat, the Isabelle, and began sailing up the Yukon in August 1902. He still planned to move his supplies to Tanacross. But when he arrived back at his trading post on the Chena River, he changed his mind. Felix Pedro had found gold!

How Fairbanks Began

Before Barnette traveled upriver with the Isabelle, he met Judge James Wickersham in St. Michael. Wickersham was a federal judge for a huge area of Alaska. Wickersham was impressed with Barnette and his plan for a trading post. He suggested Barnette name his settlement Fairbanks, after Charles W. Fairbanks, a powerful Senator from Indiana. Barnette liked the idea. He said, "If we ever needed help from the government, we would have a friend who could help us." When Barnette heard about Pedro's gold find, he decided to use the name Fairbanks for the settlement on the Chena River instead of his planned Tanacross store. He convinced the people with him to agree.

When Barnette and the Isabelle's crew heard about Pedro's discovery, they quickly left the boat and the settlement. They rushed to stake claims on creeks and likely gold spots about 12 miles (19 km) north. This was near the mountain and creek Pedro named after himself. Staking a claim was simple. Each man could pick a certain amount of land. They marked it with posts at each corner. Each claim had to be officially recorded. Barnette declared himself the temporary recorder until an official one arrived. Most men also reported their claims at the official office in Circle. To get more land, Barnette had legal permission to act for several relatives in Ohio. He staked claims in their names, giving him control over a large part of the gold-rich land.

News of Pedro's discovery spread in the months after Barnette arrived in September 1902. In December, Barnette wrote to a friend that 1,000 people had left Nome for Fairbanks. He expected half of Dawson City to arrive before spring. In January 1903, Barnette's cook, Jujiro Wada, arrived in Dawson City with news of the gold. On January 17, 1903, the Yukon Sun newspaper had a big headline: "RICH STRIKE MADE IN THE TANANA." This caused miners from the Yukon to rush to Fairbanks. It was the first big gold rush in the settlement's history.

The Gold Rush Boom

When miners from Nome, Dawson, and other places arrived in the Tanana Valley, they were often disappointed. Hundreds of claims were staked, but none were as good as Pedro's first discovery. Those had been taken by the Isabelle crew and other early arrivals. Also, some men, like Barnette, had legal rights to claim land for others. This meant they could make many claims. One newspaper reported that one man claimed 144 plots of 20 acres (81,000 m2) each. Around Barnette's trading post, town lots were claimed for $2.50 each. There was tough competition for the best spots. At the mouth of the Chena River, a rival settlement called Chena started. Land speculation was wild in Chena, and claims were often stolen. People sometimes used firearms to protect their land.

Historians estimate that by spring 1903, between 700 and 1,000 men arrived in the Tanana Valley. This put a huge strain on Barnette's food supplies. Prices quickly went up. Miners complained about Barnette charging $12 for a bag of flour and making them buy whole cases of canned food. They gathered outside his store and demanded lower prices, threatening to burn it down. Barnette said he had armed men inside. Both sides reached a compromise. Soon after, Barnette left south with his wife by dog team. He planned to find investors to buy more supplies.

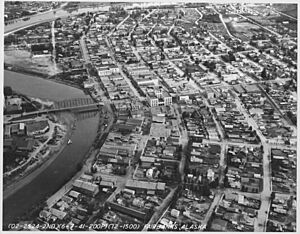

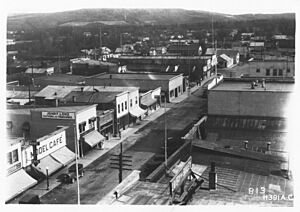

In April, Judge Wickersham arrived. He was looking for a place for the courthouse, jail, and government offices for the Third District courts. He later described Fairbanks as "A half-dozen new squat log structures, a few tents ... a small clearing in the primitive forest." Wickersham looked at Chena as a possible site, but he chose Fairbanks. This was partly because Barnette's partner, Frank Cleary, gave Wickersham a valuable piece of land. Wickersham asked Cleary to name the two main streets Cushman and Lacey, after U.S. Representatives.

Wickersham estimated 500 people in town, while another count said 1,000. There were 387 houses being built, six saloons, and no churches. Before spring, Wickersham published the first newspaper, the Fairbanks Miner, using a typewriter. It sold seven copies at $5 each. But even as Wickersham's courthouse was being built, unhappy miners were leaving. Hundreds left on rafts downriver or on steamers to Dawson City. By June 1903, cabins on city lots were selling for as little as $10. Meanwhile, Barnette sold two-thirds of his store to the Alaska Commercial Company. He also arranged for a post office to be set up in his settlement.

In fall 1903, the flow of miners leaving the Tanana Valley stopped. This was because major gold strikes were made north of Fairbanks. The gold was deeper than in the Klondike, and it took time to dig to it. At Cleary Creek, miner Jesse Noble found what became the richest gold vein in Alaska. Getting the gold out was slow because there was almost no heavy machinery to remove the dirt above the gold layers. The gold discoveries of 1903 reversed the trend of people leaving. By Christmas 1903, there were between 1,500 and 1,800 miners in the valley. Another food shortage happened in the winter of 1903. It was only helped by the food Barnette had brought in after his trip.

Despite the food shortage, more buildings were constructed. The Northern Commercial Company built a store to replace Barnette's cabin. Wickersham recorded many businesses, including 500 houses and 1,200 people. To manage the growing population, the settlement voted on November 10, 1903, to officially become a town. The vote passed, and Barnette was sworn in as the city's first mayor the next day.

Fairbanks Becomes a City

Barnette's first act as mayor was to ask the federal government to sell its military food supplies from nearby posts. This helped with the food shortage. Other actions followed: licensing a telephone company, setting up garbage collection, fire protection, and a one-room school (which closed later that winter due to lack of money). Barnette used his position to give long-term contracts for city services to his family members. His brother-in-law, James W. Hill, got a 25-year contract to provide electricity, drinking water, and steam heat to the city. In 1904, Barnette arranged for regular supply shipments to Fairbanks, and the town kept growing. Besides the local telephone system, Fairbanks was connected to the outside world by the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System. This system was extended from Eagle to Nome in 1903 and passed through Fairbanks.

Gold production jumped from $40,000 in 1903 to $600,000 in 1904, and then to $6 million in 1905. This growth and the rising population led to more activity. Barnette opened the town's first bank on September 9, 1904. A month earlier, two Catholic priests built the town's first church, Immaculate Conception Church. Also in 1904, railroad construction began in Fairbanks and Chena. Low water on the Chena River prevented steamboats from reaching Fairbanks. So, a railroad line was built from the Tanana River at Chena to Fairbanks and the mines north of town. Construction of the Tanana Mines Railroad (later the Tanana Valley Railroad) finished in Fairbanks on July 17, 1905. Two new banks opened in 1905, as did the city's first greenhouse and a new $10,000 bridge across the Chena River. In June 1905, the bridge caused the biggest flood in the young city's history. A bridge upstream collapsed, and the wreckage got caught in the new bridge, blocking the river. The river rose, flooding the town. The bridge had to be dynamited to stop the flood. The next year, a fire destroyed most of Fairbanks, causing an estimated $1.5 million in damage. The town was quickly rebuilt. The town's first hospital, St. Joseph's, was built on the north bank of the Chena. Because the hospital was run by a Catholic religious group, Immaculate Conception Church was later moved across the Chena River and placed next to the hospital. In 1907, Barnette's bank had to close temporarily due to a financial crisis and legal problems. A new school was built, which held 150 students. Other schools were built on the north side of the Chena River, which was separate from the main town.

In 1908, the U.S. Army Signal Corps built a radiotelegraph tower in town. This replaced the cable telegraph system to Valdez and Seattle. The 176-foot (54 m) tower was the tallest structure in town for many years. In 1909, Fairbanks' gold production reached its highest point at over $9.5 million. The town saw its first library open that year. The Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, the city's longest-running newspaper, also began publishing.

Bad investments caused the bank founded by Barnette to fail in January 1911. At that time, it held over $1 million in deposits from Fairbanks residents. In Fairbanks, many people believed Barnette had taken money from the bank. Even though he was found guilty of only one of 11 charges against him, Barnette had a bad reputation in Fairbanks. For years afterward, Fairbanks newspapers called any robbery "Barnetting" the subject.

The accusations against Barnette were big news in a town that usually had very little crime.

Fairbanks' Decline

In 1911, the Fairbanks Commercial Club, a group of businesses, created the slogan "Fairbanks, Alaska's Golden Heart." This slogan is still the city's motto today. In that year, Fairbanks had over 3,500 people, making it the largest city in Alaska. Thousands more lived in mining camps outside the city. But 1910 marked the start of a decline for Fairbanks. That year, less than $6 million in gold was produced. By 1911, production was half of what it had been in 1909. By 1918, it was only ten percent of the 1909 total. This drop in gold production caused businesses to close. Stores that sold to miners closed, as did those that supported the mines directly. World War I caused a further decline as young men from the town were drafted and sent overseas. The war also had economic effects. A local judge later said the war "set Fairbanks back by 10 years" because it stopped construction and sent men away. After the war, the 1918 flu pandemic was very bad in Alaska. It killed between 2,000 and 3,000 people in the territory. By 1923, the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner estimated fewer than 1,000 people lived in the city, and almost none in the mining camps outside town.

Stopping the Decline

Even though Fairbanks was declining, two big projects helped lessen the worst effects of the post-gold rush slowdown: the building of the Alaska Railroad and the creation of the University of Alaska.

The Alaska Railroad

In 1906, an expert predicted that a railroad link to the ocean would allow gold miners to bring in heavy equipment. This would help them process large amounts of lower-grade ore. He said it would make living cheaper for miners and allow them to work on land that couldn't be mined before. Eight years later, the U.S. Congress approved $35 million to build the Alaska Railroad system. News of this funding caused celebrations among Fairbanks residents. They hoped its construction would greatly help the local economy.

In 1917, the Alaska Railroad bought the Tanana Valley Railroad, which had struggled during the war. The railroad line was extended westward. It reached the town of Nenana and met a construction team working north from Ship Creek, which was later renamed Anchorage. Until the railroad was finished and coal from Healy became available, Fairbanks burned wood for heating and electricity. In 1913, the town burned between 12,000 and 14,000 cords of wood. The Northern Commercial Company, which owned the power plant, burned 8,500 cords by itself.

President Warren G. Harding visited Fairbanks in 1923. He was there to hammer in the ceremonial final spike of the railroad at Nenana. The rail yards of the Tanana Valley Railroad were changed for use by the Alaska Railroad. Fairbanks became the northern end of the line and its second-largest depot.

The University of Alaska

One year before President Harding's visit, the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines opened. Today, it's known as the University of Alaska Fairbanks. It started with just six students. The idea for the school came from James Wickersham, who had become Alaska's representative in Congress. In 1915, Wickersham got a bill approved to fund the college. After the bill passed, he traveled to Fairbanks. He chose a site on a hill four miles (6.4 km) west of Fairbanks. This area is now called College, Alaska and is often seen as part of Fairbanks. On July 4, 1915, he laid the cornerstone for the school, even though he didn't have official permission yet.

The school's site was just north of the U.S. Agricultural Experimental Station (Tanana Valley). This was a farm created in 1907 by Charles Christian Georgeson. The farm was a project by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to see if farming was possible in Interior Alaska. By 1916, a year after the University of Alaska was founded, the experimental farm employed 20 people. As mining slowed down in Fairbanks, some miners started farming. Under the Homestead Act, many miners applied for land from the government and set up farms around the city. A 1919 survey found 94 homesteads within six miles (9.7 km) of Fairbanks. It also listed two tungsten mills and 16 gold mills.

Farming in the area was encouraged by food shortages in the winters of 1913, 1915, and 1916. Fairbanks businessmen also supported farming. Wickersham provided more funding for the experimental farm. The Tanana Valley Railroad gave free grain seeds from a Swedish experimental farm. William Fentress Thompson, the editor of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, often wrote articles supporting more farming. Important Fairbanks businessmen formed the Alaska Loyal League, a group that encouraged farming. Farmers also created the Tanana Valley State Fair in 1924 to show off their farming success. It is Alaska's oldest state fair and still runs today. Despite these efforts, farming in Fairbanks had limited success. A farmers' bank, started in 1917 to give loans for equipment, closed two years later. And while the Alaska Railroad made it cheaper to ship tractors and other farm equipment, it also brought a steady supply of food shipments to Fairbanks. In 1929, Alaska farms only met about 10 percent of the state's food needs. By 1931, the University of Alaska had grown so much that the experimental farm became part of the school.

The Dredging Era

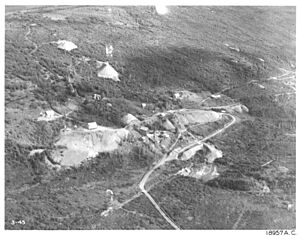

After the Alaska Railroad was finished, it became affordable to bring in heavy equipment. This allowed the building of gold dredges to work the large amounts of lower-grade gold ore left after the Fairbanks Gold Rush. A great example of this is the Davidson Ditch. This was a 90-mile (140 km) water channel built between 1924 and 1929 to provide water for gold dredging. The Fairbanks Exploration Company (FE Co.), a part of a larger mining company, built both the water channel and many of the dredges that used its water to process ore. Large-scale dredging began in 1928, and FE Co. became the town's biggest employer. It built the largest power plant in Alaska to provide electricity for the dredges. It also built pumping stations to supply them with water from the Chena and other rivers.

In 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt set the price of gold at $35 per ounce. This price increase encouraged more mining and protected Fairbanks from the Great Depression. When Roosevelt called for a "bank holiday" to help with the depression, Fairbanks banks said they didn't need one. Large-scale dredging reached its peak in 1940, when 209,000 ounces of gold were produced in the Fairbanks area. After World War II started for the United States, the government closed most gold-mining operations. They were considered not essential to the war effort.

In 1932, Fairbanks' two-story school, built in 1907, burned down. A new, $150,000 three-story concrete art deco building was suggested as a replacement. After much debate, a $100,000 bond measure was approved in 1933. On January 22, 1934, the new school opened. It had space for about 500 students. But the town's growth required it to be updated and expanded in 1939 and 1948.

Paving Fairbanks' Streets

Until 1938, Fairbanks did not have paved streets. The town's dirt roads turned to dust in summer and thick mud in spring and fall. This caused problems as Fairbanks' population grew in the 1930s. In 1937, the mayor of Fairbanks, E. B. Collins, suggested using a federal grant and city money to pave the roads. But voters turned him down. The next year, he tried again and was successful. By 1940, the first 0.25 miles (0.40 km) of paved road were finished.

Aviation Takes Off

Around the time the Alaska Railroad was completed and the dredging era began, Alaska's aviation industry started to grow. The first airplane flight in Alaska happened in Fairbanks on July 4, 1913. A barnstormer flew from a field south of town. The aircraft had been shipped from Seattle. The pilot later tried to sell the plane, but no one bought it. Alaska's first commercial aircraft didn't arrive until June 1923. That's when Noel Wien began flying a Curtiss JN-4 on mail routes between Fairbanks and isolated communities. From Fairbanks, Wien became the first person to fly to Anchorage and cross the Arctic Circle in an airplane.

Because Alaska had limited roads and railways, the government saw the benefits of air travel. In 1925, the government allowed spending up to $40,000 per year on airfield construction. Between that year and 1927, over 20 airfields were built. By 1930, Alaska had over 100. In Fairbanks, airplanes flew from a field that was also used as a baseball diamond. In 1931, the city bought the field, added facilities, and named it Weeks Field. By the late 1930s, there were over four dozen airplanes in the town of about 3,000 people. This gave Fairbanks the reputation of having the most airplanes per person in the world. Because Fairbanks is located halfway between New York City and Tokyo, it became a very important stop on the first around-the-world flights. Wiley Post's 1933 solo flight around the world stopped in Fairbanks, as did Howard Hughes' 1938 effort.

Military flights also used Fairbanks as a base. In 1920, the first flight from the rest of the United States to Alaska used Fairbanks as a base. In 1934, a group of Martin B-10 bombers flew from Washington, D.C. to Fairbanks. This was supposedly to show that long-range bombers could be deployed. But in reality, the bombers flew photo missions to find locations for military airfields to be built in Alaska.

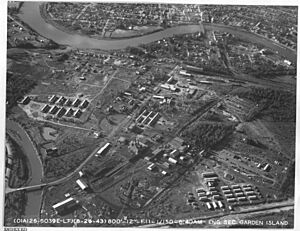

The Military Era

In his last public speech, U.S. Army General Billy Mitchell said, "I believe that, in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world... I think it is the most important strategic place in the world." That year, Congress passed a law to create a new airbase in Alaska for cold-weather testing and training. A survey team visited Fairbanks in 1936. In 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an order setting aside 6 square miles (16 km2) of public land east of Fairbanks for the new airbase. It was named Ladd Army Airfield after Army pilot Arthur Ladd. Construction began in summer 1939, just a few days before Germany invaded Poland to start World War II. The first runway was finished in September 1940, and the base was officially opened then, even before most of the buildings were complete.

In the first winter after the opening, soldiers practiced flying and working on aircraft in very cold conditions. Over 1,000 workers, mostly hired from outside Alaska, worked on the project through 1941. Even with these outside workers, the construction effort caused almost no unemployment in Fairbanks. This created a high demand for workers. Fairbanks' economy grew, and the city's second radio station, KFAR, began broadcasting on October 1, 1939. Hangars and base buildings were finished in summer 1941. But the second winter of cold-weather testing was interrupted by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

World War II in Fairbanks

Fairbanks learned about the attack on Pearl Harbor from civilian shortwave radio operators. They passed the news to the U.S. Army base. Over 200 civil defense volunteers immediately signed up. Their work included organizing a town blackout, blocking town airfields, and making emergency plans to evacuate the town if attacked. In June 1942, the invasion of the Aleutian Islands and the bombing of Dutch Harbor made the war's impact on Fairbanks stronger. Ladd Field's cold-weather testing team was broken up, and its soldiers were sent to strengthen Alaska's defenses in other places.

During summer 1942, more soldiers arrived in Fairbanks to replace those who had moved. Fairbanks residents were asked to work at Ladd Field. The U.S. Army believed Alaskans were best at working in cold weather. After gold mining was stopped during the war, the Army rented FE Co. offices and took supplies from Fairbanks businesses. Wartime demand and the draft caused a big shortage of workers in Fairbanks. Supplies of various foods and products were also interrupted, beyond the wartime rationing in the rest of the country. Crime also increased. Because the U.S. Army was in charge of Alaska during the war, all newspapers and letters to and from Fairbanks were checked by censors.

To help with shortages and supply the war effort, the U.S. Army and the Canadian government began building the Alaska Highway. This highway connected the Canadian road network to Alaska's Richardson Highway and Fairbanks. The highway was finished in fall 1942, and regular traffic began in 1943. As work on the highway happened, war supplies were already reaching Fairbanks by air. The Northwest Staging Route, a chain of airfields, ended at Fairbanks. Starting in February 1942, supply aircraft began landing in Fairbanks to support the war effort in Alaska. In summer 1942, talks between the United States and the Soviet Union led to an extension of the Lend-Lease program to Russia. Using the Northwest Staging Route, aircraft were flown from Great Falls, Montana, to Ladd Field. At Ladd Field, the aircraft were given to Soviet pilots, who flew them to Nome and then to the Soviet Union. Fairbanks was chosen as a transfer location because it was safer from potential Japanese attacks than Nome.

Starting in fall 1942, many Soviet soldiers arrived in Fairbanks to work with the U.S. soldiers already there. The huge Lend-Lease effort required more facilities to be built in and near Fairbanks. Ladd Field expanded, and the U.S. Army post grew until it met the city limits of Fairbanks. The University of Alaska, which had most of its students drafted, provided office and dorm space for U.S. and Soviet soldiers. Its professors also helped the war effort with special Russian language classes. Russian airmen often shopped at Fairbanks stores. They bought many consumer goods that were not available in their home country. To meet demand when Ladd Field couldn't be used due to fog, an airfield now known as Eielson Air Force Base was built southeast of Fairbanks. Although there were some disagreements between Soviet and U.S. soldiers and civilians, Lend-Lease operations in Fairbanks continued until the end of the war. When Lend-Lease ended in September 1945, 7,926 aircraft and tons of cargo had been transferred to Soviet officials in Fairbanks.

Fairbanks in the Cold War

By fall 1945, Ladd Field had grown to almost 5,000 military personnel and many acres of runways and buildings. Even with a short quiet period as the U.S. Army sent soldiers home after World War II, activity in Fairbanks stayed high as the Cold War began. The population of the Fairbanks area grew by 240 percent between 1940 and 1950. Then it doubled between 1950 and 1953. This growth put a lot of pressure on the city's services. Schools, water, power, sewer, and telephone systems were all overloaded by new arrivals and expansion. New neighborhoods grew around Fairbanks, and the city started adding them to its official area. In 1952, the city's boundaries grew from 1.3 square miles (3.4 km2) to 2.4 square miles (6.2 km2), with another 1 square mile (2.6 km2) added soon after. More than a dozen new housing areas filled the space between Fairbanks city limits and College. The city's border moved westward until it met the college town's limit. The growing town paused to remember its beginnings with the Golden Days Festival. This week-long celebration of Fairbanks history started to mark the 50th anniversary of the discovery of gold. The annual festival continues today.

The University of Alaska also grew during this time. In 1946, Congress approved money to build a Geophysical Institute to study Arctic things like the aurora borealis (Northern Lights). The institute was created in 1949. It helped the university grow as the GI Bill also boosted the number of students. Elementary education also improved. The Fairbanks Independent School District was created in 1947. It collected school taxes from areas outside the city that sent students to Fairbanks' school. The Golden Valley Electric Association, an electrical cooperative, was founded in the 1940s. It provided electricity to areas outside Fairbanks city limits. In 1953, it bought the FE Co. power plant that served Fairbanks. It provided electricity to many customers, from Fairbanks' second radio station, KFRB, to the town's largest farm, Creamer's Dairy.

A new airport opened on October 15, 1951. It replaced Weeks Field, which had been surrounded by the town's growth, including Denali Elementary School, the town's first new school since the 1930s. The new Fairbanks International Airport began serving DC-6 planes. These cut travel time from Seattle to six hours from eight. The new airport also attracted an over-the-pole test flight by Scandinavian Airlines System. But the airline eventually chose Anchorage as a refueling point for flights from Stockholm to Tokyo. Ground transportation also got better in Fairbanks. A major program to pave downtown roads began in 1953. The goal was to pave 30 blocks. New military facilities appeared around Fairbanks and further away. The Haines-Fairbanks 626-mile (1,007 km) long 8-inch (20 cm) petroleum products pipeline was built between 1953 and 1955. The city was a staging area for building the Distant Early Warning Line, the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System at Clear Air Station, and several Nike Hercules air defense missile batteries.

The first tall buildings were built in Fairbanks during this time. The eight-story Northward Building and the 100-foot (30 m) Hill Building (later Polaris Building) were built in the first half of the 1950s. The first traffic lights were installed during the same period. Fairbanks' first television station, KTVF Channel 11, began broadcasting on February 17, 1955. The city's first dedicated high school, Lathrop High (originally Fairbanks High), also began operating in 1955. In the next four years, four new elementary schools opened. This took the pressure off Main School, which became Main Junior High School.

Alaska Becomes a State

During the 1950s, people in Alaska pushed for the territory to become a state. Alaskans couldn't vote in presidential elections and had a local government with limited powers. Efforts to convince federal lawmakers to pass a statehood bill had little success. So, important officials decided to write a state constitution. This would show Alaska was ready to become a state. On November 8, 1955, 55 elected representatives gathered at the University of Alaska. They began writing a state constitution. The debates lasted over two months and created a lot of excitement in Fairbanks. The debates were broadcast on Fairbanks radio, and the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner published daily reports on the convention's progress. On February 5, 1956, the representatives signed the constitution in front of 1,000 people who filled the University of Alaska gymnasium. The building where they met was later named Constitution Hall.

On June 30, 1958, the U.S. Senate voted 64 to 20 to accept Alaska as a state. This news caused huge celebrations in Fairbanks. Residents set off fireworks, and an unplanned parade went down Cushman Street, the city's main road. An attempt to dye the Chena River gold in celebration accidentally turned it green. The celebration ended when residents used weather balloons to lift a 30-foot (9.1 m) wide wooden star, painted gold and marked with "49," into the air. The balloons lifted it, then drifted into power lines, causing a 16-minute power outage across the city.

President Dwight Eisenhower officially signed Alaska into the United States on January 3, 1959. This put the Alaska constitution into effect. The new state's constitution called for the creation of local borough governments to help manage the new state. Fairbanks and other areas were not eager to add another layer of government. In 1963, the Alaska Legislature passed a law that required the eight most populated areas of the state to form organized boroughs by 1964. Students from Fairbanks schools chose "North Star" as the Fairbanks' borough's name. The Fairbanks North Star Borough officially began on January 1, 1964.

The years after statehood saw the military boom continue to boost Fairbanks' economy and the city's growth. Fairbanks International Airport's runway was made longer to 11,500 feet (3,500 m) to handle jet aircraft. The George Parks Highway was built from Fairbanks to Anchorage and Denali National Park, encouraging tourism. Homes were built on the hills north of Fairbanks for the first time. Roads were repaved and smoothed, and sidewalks replaced dirt paths. However, this growth came with a cost. Many of the original buildings from Fairbanks' founding were torn down for "urban renewal." The very first home built in Fairbanks was demolished.

In 1960, the U.S. Air Force planned to close Ladd Airfield and move its operations to nearby Eielson Air Force Base and Elmendorf Air Force Base near Anchorage. When this decision was announced, almost everyone in Fairbanks opposed it. Although the Air Force stuck to its decision to move out of the base, the U.S. Army took over the post on January 1, 1961, and renamed it Fort Wainwright.

The arts scene in Fairbanks also grew during this time. The Fairbanks Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1959, and the Fairbanks Drama Association was created in 1963. The Alaska Goldpanners baseball team was founded in 1959 as the city's first professional sports team. The next year, the Goldpanners hosted their first annual Midnight Sun Baseball Game. This tradition had been happening since 1905 and continues today under the Goldpanners. Throughout the 1960s, Fairbanks became much more like small towns in the rest of the U.S. as communications, transportation, and utilities improved.

The Great Flood of 1967

In 1967, Alaska celebrated 100 years since the United States bought it from Russia. To celebrate, Fairbanks residents built A-67 (later Alaskaland and now Pioneer Park). This was a theme park celebrating the history of Fairbanks and Alaska. Located away from downtown Fairbanks, it features pioneer cabins, historic exhibits, and the steamer SS Nenana. This was one of the steamboats that traveled Interior Alaska rivers during the gold rush era. The summer fair that opened the park in July 1967 was attended by U.S. Vice President Hubert Humphrey. But it had problems with rain, money issues, and low attendance.

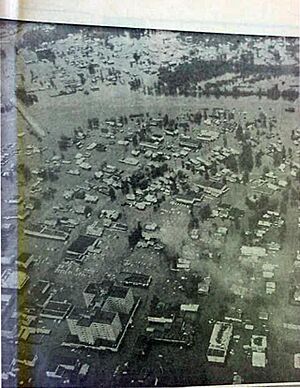

One month after Alaska's centennial celebration, the worst disaster in Fairbanks' history happened. In July 1967, Fairbanks received 3.34 inches (8.5 cm) of rain. This was almost double the average for July. Then, between August 11 and August 13, Fairbanks and the Tanana Valley had the heaviest rainfall ever recorded. In the 24 hours before noon on August 12, 3.42 inches (8.7 cm) of rain fell. The average rainfall for the entire month of August is 2.20 inches (5.6 cm). In August 1967, 6.20 inches (15.7 cm) fell on Fairbanks and the Tanana Valley.

The huge amount of rain turned the Chena River into a raging flood. On August 14, it went past flood stage and kept rising. Because no water monitoring equipment had been installed upstream of Fairbanks, residents didn't know how big the flood would be. All day and night on August 14, the water rose. It flooded the A-67 site. Volunteers allowed water to fill the hold of the SS Nenana to keep it from floating away and damaging buildings. In downtown Fairbanks, hundreds of volunteers built a sandbag dike around St. Joseph's Hospital, but it didn't work. As the water went over the emergency dike, doctors, nurses, and patients moved to the University of Alaska on College Hill.

The university, which is built on high ground, became an evacuation point and emergency shelter for thousands of flood refugees. The university's civil defense director expected between 700 and 800 people to take shelter. But between 7,000 and 8,000 showed up as the water rose through August 14 and 15. They crowded into facilities designed for just over 1,000 students. A helipad was set up in a parking lot, and helicopters from Eielson Air Force Base brought supplies to the refugees. Fairbanks' power plant was flooded. So, the university relied on its own power plant to provide electricity for the refugees. When the rising water threatened to flood the plant, hundreds of refugees gathered to build barriers and pump out the plant's basement.

The flood had a massive impact on Fairbanks. Four people were killed, and the damage was in the hundreds of millions of dollars. It helped push the city's last farm, Creamer's Dairy, into bankruptcy. It also forced the closure of St. Joseph's Hospital. Fairbanks residents responded to the problems with courage. The annual Tanana Valley State Fair was delayed but not canceled. Seven thousand dollars were raised to buy Creamer's Dairy and turn it into a bird sanctuary. KTVF, one of the few businesses with flood insurance, rebuilt its studio and became the first Fairbanks TV station to broadcast in color, four months after the flood. When two votes to build a government-run hospital were turned down by Fairbanks voters, residents raised $2.6 million from private donations and $6 million from the state and federal government to build Fairbanks Memorial Hospital.

After the flood, the U.S. Congress passed the Flood Control Act of 1968. This provided money to build the Chena River Lakes Flood Control Project on the Chena River upstream of Fairbanks. The project was built between 1973 and 1979. It diverts the Chena River into the Tanana River when the Chena rises too high. A chain of dikes was built along the Tanana River to prevent high water from that river from flooding Fairbanks from the south. Many businesses received low-interest federal loans to rebuild, which they did quickly. In 1969, Fairbanks was one of 11 cities honored as an "All-America City" by Look magazine and the National League of Cities. This was in honor of its success in recovering from the flood.

The Oil Boom

On March 12, 1968, an oil drilling team found oil near Prudhoe Bay, about 400 miles (640 km) north of Fairbanks. This discovery of the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field caused a huge boom in Fairbanks. It was the closest city to the oil field. After failed attempts to transport oil by sea tankers and airplanes, the oil companies decided to build a pipeline. Plans were ready to go forward, but legal challenges stopped the project in 1970. One set of challenges, from Alaska Native groups in the pipeline's path, was settled by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971. Thirteen major Alaska Native corporations and many smaller ones were created to manage the money and land given by the federal government under this act. In 1972, Fairbanks became the main office for Doyon, Limited, the largest of these corporations.

Fairbanks' economy, which had a brief boom after the oil discovery, slowed down as legal challenges continued. The challenges ended when the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act was approved in late 1973. When pipeline work began in early 1974, it caused a boom in Fairbanks unlike anything since the city's founding. Alyeska Pipeline Service Company alone spent an estimated $800,000 a day in Fairbanks. The city housed the construction headquarters on Fort Wainwright. Tens of thousands of workers poured into the city. This strained the economy, services, and public works. The population of the Fairbanks North Star Borough increased by 40 percent between 1973 and 1976. The number of businesses in the area doubled during the same period.

This population increase caused many problems. The Municipal Utilities Service, which ran telephone service, ran out of phone numbers. The waiting list for phone connections grew to 1,500 people. Demand for electricity was so high that the power company told homeowners to buy generators to deal with frequent power dips. Home prices skyrocketed. A home that sold for $40,000 in 1974 was bought for $80,000 in 1975. Rent for homes and apartments also went up sharply due to rising prices and demand from pipeline workers. Two-room log cabins with no plumbing rented for $500 per month. One two-bedroom home housed 45 pipeline workers who shared beds on a rotating schedule for $40 per week.

The soaring prices were driven by the high salaries paid to pipeline workers who were eager to spend their money. These high salaries caused a demand for higher wages among non-pipeline workers in Alaska. Businesses not related to the pipeline often couldn't keep up with the demand for higher wages, and job turnover was high. Yellow Cab in Fairbanks had an 800 percent turnover rate. A nearby restaurant had a turnover rate of over 1,000 percent. Many jobs were filled by high school students promoted beyond their experience. To meet the demand, Lathrop High School ran in two shifts: one in the morning and one in the afternoon. This allowed students to also work eight hours a day. More wages and more people meant higher demand for goods and services. Waiting in line became a normal part of life in Fairbanks. The Fairbanks McDonald's became the second highest-selling McDonald's in the world, only behind the recently opened Stockholm store. Alyeska and its contractors bought in large amounts from local stores. This caused shortages of everything from cars to tractor parts, water softener salt, batteries, and ladders.

By 1976, after the city's residents had dealt with a rise in crime, overloaded public services, and many new people unfamiliar with Alaska customs, 56 percent said the pipeline had changed Fairbanks for the worse. In downtown Fairbanks, overcrowding, traffic problems, and drunken behavior by pipeline workers caused businesses to move to malls built away from downtown. New shopping centers like Gavora Mall and Bentley Mall away from the city center led to the construction of highways that bypassed downtown Fairbanks.

Fairbanks After the Boom

| 1910 | 3,541 |

| 1920 | 1,155 |

| 1930 | 2,101 |

| 1940 | 3,455 |

| 1950 | 5,771 |

| 1960 | 13,311 |

| 1970 | 14,711 |

| 1976 | 34,554 |

| 1980 | 22,645 |

| 1985 | 27,099 |

| 1990 | 30,843 |

| 1995 | 32,384 |

| 2000 | 30,224 |

| 2008 (Est.) | 35,132 |

Pipeline construction ended in 1977. This began a slow decline in Fairbanks' economy. The loss of construction spending was mostly balanced by state spending. Taxes on oil flowing through the pipeline were used for low-interest loans, grants, and business help. This poured money into the city. To encourage businesses to return to downtown Fairbanks, the city tore down many of the bars popular with pipeline workers. It tried to attract a hotel or major business to the location. This effort was not successful, and the land remained empty until the late 1990s. Redevelopment of the Fairbanks airport was more successful. A new terminal built in 1984 was used until 2009.

With the help of grants and funding, cultural events and organizations grew in Fairbanks. The Fairbanks Light Opera Theatre was created in 1970. Groups like the Fairbanks Concert Association and the Northstar Ballet were also started around the same time. Fairbanks' largest arts event, the Summer Arts Festival, began in 1980 and continues today.

Sports facilities also benefited from the state funding. The Big Dipper Ice Arena, a converted airplane hangar moved from Tanacross in 1969, had a $5 million renovation in 1981. This allowed it to host the Arctic Winter Games the next year. In 1979, the University of Alaska built the Patty Center, the first full indoor ice arena in Interior Alaska. The same year, the school started an NCAA Division I hockey team.

Wien Air Alaska, which had its headquarters in Fairbanks, was the state's largest private employer. But it went out of business in 1983. This shutdown cost hundreds of jobs in Fairbanks. This was a sign of more problems to come. In 1986, Saudi Arabia increased oil production, and oil prices dropped sharply. Alaska banks failed, construction stopped, and many bankruptcies and home foreclosures happened. A common practice in Fairbanks was for workers to leave their house keys at local banks before flying out of Alaska. This made the foreclosure process faster. Although an expansion of Fort Wainwright helped the construction industry during this time, Fairbanks lost about 3,000 jobs between 1986 and 1989. The U.S. Army's 6th Infantry Division was stationed at Fort Wainwright in late 1987. But it was reduced to a single brigade and renamed in 1993.

This period in the city's history also had some good moments. To celebrate the 25th anniversary of Alaska statehood, the city ordered a 25-foot (7.6 m) sculpture of an Alaska Native family. It was meant to represent "Alaska's first family." The statue is the main feature of Golden Heart Plaza, which was opened in 1986 on the south bank of the Chena River in downtown Fairbanks. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II briefly met in Fairbanks. This happened because their two separate visits to Asia would cross over Alaska at the same time. About 10,000 people attended their meeting. It was the largest gathering of people in Fairbanks' history.

Modern Fairbanks

As oil prices rose in the 1990s, Fairbanks' economy improved. The city also got a boost from the return of gold mining in the area. The Fort Knox Gold Mine north of Fairbanks opened in 1997 after several years of development. Another gold project is likely to be developed in the next ten years. The same year Fort Knox Mine opened, Alyeska moved 300 jobs from Anchorage to Fairbanks. This made Fairbanks the base of its operations for the first time in many decades.

The U.S. military remains a large presence in Fairbanks. The U.S. 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team of the 25th Infantry Division is based at Fort Wainwright. Eielson Air Force Base remains a training and logistics hub for the U.S. Air Force. In 2009, the U.S. Army announced it was thinking about basing 1,000 more soldiers at Fort Wainwright because it has plenty of space.

Utilities and other services have also changed a lot since 1990. Fairbanks Memorial Hospital was renovated and expanded in 1976, 1985, 1995, and 2000. In 2009, the hospital opened a new heart care center during its latest expansion. Bassett Army Hospital on Fort Wainwright had a $132 million renovation in 2005. To meet the demand for a convention center and large sports arena, the city paid for the construction of the Carlson Center. This is a 5,000-seat arena that opened in 1990. In 1996, the city of Fairbanks sold its utilities to a private company. About $74 million from the sale was put into a savings account called the Fairbanks Permanent Fund. This fund is invested and managed like the Alaska Permanent Fund, but residents do not receive any income from it.

Images for kids

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |