History of Schleswig-Holstein facts for kids

The history of Schleswig-Holstein tells the story of this region from ancient times until it became the modern state of Schleswig-Holstein.

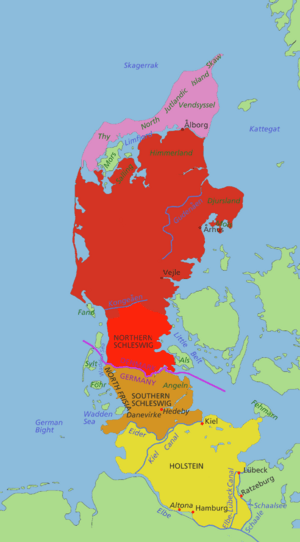

The Jutland Peninsula is a large piece of land in Northern Europe. Today's Schleswig-Holstein is at its base. The area called Schleswig is also known as Southern Jutland (Sønderjylland). Old stories suggest that Jutland was split into a northern and southern part, with the Kongeå River as the border.

Evidence from old digs and Roman writings shows that the Jutes lived in the Kongeå region and further north. The Angles lived where the towns of Haithabu and Schleswig later appeared. The Saxons lived in Western Holstein, and Slavic Wagrians lived in Eastern Holstein. Later, the Danes settled in Northern and Central Schleswig during the Viking age. The Northern Frisians arrived in Western Schleswig around the year 900.

Contents

After the Dark Ages Migrations

After many Angles moved to the British Islands in the 5th century, the land of the Angles became more connected with the Danish islands. This likely happened through Danes moving in. Later, contacts also grew between the Danes and people in the northern part of the Jutland peninsula.

Looking at place names today, the southern border of the Danish language seemed to follow the Treene river, along the Danevirke (an old wall), and then from the Schlei river to Eckernförde. The West coast of Schleswig was where the Frisian language was spoken.

After Slavic people moved in, the eastern part of modern Holstein was settled by Slavic Wagrians.

Nordalbingia and Wagria

Besides northern Holstein and Schleswig, which were home to Danes, there were also Nordalbingia in Western Holstein and Wagria in Eastern Holstein.

Nordalbingia was one of the four main areas of the medieval Duchy of Saxony. It included Dithmarschen, Holstein, and Stormarn.

The Wagri or Wagrians were a Slavic tribe living in Wagria (eastern Holstein) from the 9th to 12th centuries. They were part of the Obodrites group.

Conquest of Nordalbingia

In the Battle of Bornhöved (798) in 798, the Obodrites, led by Drożko, teamed up with the Franks. They defeated the Nordalbingian Saxons.

After this defeat, where the Saxons lost 4,000 people, 10,000 Saxon families were moved to other parts of the empire. Areas north of the Elbe river (Wagria) were given to the Obodrites. However, the Danes soon attacked the Obodrites. Only with help from Charlemagne were the Danes pushed back from the Eider river.

Danes, Saxons, Franks Fight for Control

As Charlemagne expanded his empire in the late 8th century, he met a Danish army. They successfully defended Danevirke, a strong defensive wall across the south of the territory. A border was set at the Eider River in 811.

The Danes' strength came from three things:

- Good fishing.

- Fertile land for farming and pastures.

- Taxes and customs from the market in Haithabu. This market was important because all trade between the Baltic Sea and Western Europe passed through it.

The Danevirke was built just south of a road where boats and goods had to be pulled for about 5 kilometers between a Baltic Sea bay and a small river connected to the North Sea. Here, in the narrowest part of southern Jutland, the important trading market of (Haithabu or Hedeby) was set up. It was protected by the Danevirke wall. Hedeby was located on the Schlei inlet, across from what is now the City of Schleswig.

The wealth of Schleswig, shown by amazing old finds, and the taxes from Haithabu, were very tempting. A separate kingdom of Haithabu was started around the year 900 by the Viking leader Olaf. But Olaf's son was killed in battle against the Danish king, and his kingdom disappeared.

The southern border changed several times. For example, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto II took over the region between the Eider river and the Schlei inlet from 974 to 983. This area was called the March of Schleswig, and it encouraged German settlement. Later, Haithabu was burned by Swedes. The situation became stable under King Sweyn Forkbeard (986–1014), but attacks on Haithabu continued. Haithabu was finally destroyed by fire in 1066. As a writer named Adam of Bremen reported in 1076, the Eider River was the border between Denmark and the Saxon lands.

For a long time, the land north of the Elbe river was a battleground for Danes and Germans. Danish experts point to Danish place names north of the Eider and Danevirke as proof that most of Schleswig was once Danish. German experts, however, say it was always "Germanic" because Schleswig became its own duchy in the 13th century and was influenced from the south. The Duchy of Schleswig, or Southern Jutland (Sønderjylland), was a Danish fief (land given in exchange for loyalty). But it was often quite independent from Denmark, much like Holstein. Holstein was a fief of the Holy Roman Empire. The border between Schleswig and Holstein was often seen as the border of the Holy Roman Empire.

12th Century

The Earl Knud Lavard, son of a Danish king, became Duke of Southern Jutland. His son became the Danish king. Later, a branch of the royal family received Southern Jutland (Slesvig) as their own territory. This duchy helped pay for the royal princes. Rivalries over who would be king and the duchy's desire for independence led to long fights between the Dukes of Schleswig and the Kings of Denmark from 1253 to 1325.

At that time, the Holy Roman Empire expanded north. It put the Schauenburg family in charge of Holstein as counts, under German rule. Knud Lavard had also gained parts of Holstein for a while, which caused conflict with Count Adolphus I (Schauenburg). Both wanted to expand their power and control the Wagrian tribe. Count Adolphus II, son of Adolphus I, took over and created the County of Holstein in 1143, with borders similar to today. Holstein became Christian, many Wagrians were killed, and the land was settled by people from other areas. Soon, Holsatian towns like Lübeck and Hamburg became strong trading rivals on the Baltic Sea.

13th Century

Adolphus II (1128–1164) managed to take back the Slavic Wagri lands and founded the city of Lübeck to control them. Adolphus III (died 1225) received Dithmarschen from the emperor. But in 1203, he had to give Holstein to Valdemar II of Denmark. This was confirmed by the emperor and the pope, which made the nobles in Holstein angry.

In 1223, King Valdemar and his oldest son were kidnapped by Count Henry I, Count of Schwerin. They were held captive for several years. Count Henry demanded that Valdemar give up the land he had taken in Holstein 20 years earlier. Danish messengers refused, and Denmark declared war. The war ended with a Danish defeat in 1225, and Valdemar had to give up his conquests to be released.

Valdemar was freed in 1226 and asked the Pope to cancel his promise, which the Pope did. In 1226, Valdemar attacked the nobles of Holstein and had some early success.

On July 22, 1227, the armies fought at Bornhöved in Holstein in the second Battle of Bornhöved. This battle was a big win for Adolphus IV of Holstein. During the battle, troops from Dithmarschen left the Danish army and joined Adolphus. In the peace that followed, Valdemar II gave up his lands in Holstein for good, and Holstein was permanently secured for the house of Schauenburg.

King Valdemar II, who still held the former imperial land north of the Eider, made Schleswig a duchy for his second son, Abel, in 1232. Holstein, after Adolphus IV died in 1261, was split into several smaller areas by his sons and grandsons.

14th Century

The connection between Schleswig and Holstein grew stronger in the 14th century. The ruling class and settlers moved into the Duchy of Schleswig. Local lords in Schleswig wanted to keep Schleswig independent from Denmark and strengthen its ties to Holstein within the Holy Roman Empire. This desire for independence continued for centuries.

The rivalry between the kings of Denmark and the dukes of Schleswig was costly. Denmark had to borrow a lot of money. The Dukes of Schleswig were allied with the Counts of Holstein, who became the main lenders to the Danish Crown.

When King Eric VI of Denmark died in 1319, Christopher II of Denmark tried to take the Duchy of Schleswig. But Valdemar's guardian, Gerhard III, Count of Holstein-Rendsburg, pushed back the Danes. Gerhard helped Duke Valdemar become King of Denmark (as Valdemar III in 1326). In return, Gerhard himself received the Duchy of Schleswig. King Valdemar III was seen as a usurper because he was forced to sign the Constitutio Valdemaria (June 7, 1326). This document promised that The Duchy of Schleswig and the Kingdom of Denmark must never be united under the same ruler. This was the first time Schleswig and Holstein were united, though only under the same person.

In 1330, Christopher II got his throne back. Valdemar III of Denmark gave up his kingship and returned to being Duke of Schleswig. As a reward, Gerhard received the island of Funen. In 1331, war broke out between Gerhard and King Christopher II, ending in a Danish defeat. Denmark was left without a king between 1332 and 1340. Gerhard was killed in 1340 by a Dane.

In 1340, King Valdemar IV of Denmark began his long effort to reclaim his kingdom. He succeeded in regaining control of many parts of Denmark but failed to get Schleswig. Its ducal line remained mostly independent.

This was a time when almost all of Denmark was controlled by the Counts of Holstein, who held different parts of Denmark as payment for their loans. King Valdemar IV started to get his kingdom back piece by piece. He married Helvig of Schleswig, the sister of his rival. The son of Duke Valdemar V of Slesvig, Henry, was given the Duchy in 1364. But he could not get back more than the northernmost parts because he couldn't repay the loans. With him, that line of dukes ended. The true holder of the lands was the count of Holstein-Rendsburg.

In 1372, Valdemar Atterdag turned his attention to Schleswig and conquered Gram and Flensburg. Southern parts of Schleswig had been mortgaged to German nobles by Duke Henry I, Duke of Schleswig (died 1375), the last duke of that line. The childless Henry gave his rights to King Valdemar IV in 1373. However, the German nobles refused to let the king repay the mortgage.

In 1374, Valdemar bought large areas of land in the province. He was about to start a campaign to conquer the rest when he died on October 24, 1374. Duke Henry I died shortly after in 1375. When the male lines in both the kingdom and the duchy ended, the counts of Holstein-Rendsburg took over Schleswig. The nobles quickly gained more control of the Duchy, stressing that it was independent of the Danish Crown.

In 1386, Queen Margaret I of Denmark, daughter of Valdemar IV, gave Schleswig as a hereditary fief to Count Gerhard VI of Holstein-Rendsburg. He had to promise loyalty to her son King Oluf. Gerhard eventually gained control of all of Holstein except for a small part. This merging of power marks the beginning of the union of Schleswig and Holstein.

15th Century

Gerhard VI died in 1404. Soon after, war broke out between his sons and Eric of Pomerania, Margaret's successor on the Danish throne. Eric claimed South Jutland as part of Denmark. This claim was formally recognized by the Emperor in 1424. But it wasn't until 1440 that the fighting ended. Count Adolphus VIII, Gerhard VI's son, was given the hereditary duchy of Schleswig by Christopher III of Denmark.

In 1409, King Eric VII of Denmark forced the German nobles to give him Flensburg. War started in 1410, and Eric conquered Als and Ærø. In 1411, the nobles took Flensburg back. In 1412, both sides agreed to let a count from Mecklenburg settle the dispute. He gave the city to Denmark, and Margaret I of Denmark took control. She died in Flensburg shortly after from the plague.

In 1424, Emperor Sigismund ruled that Schleswig rightfully belonged to the King of Denmark. He based this on the fact that the people of Schleswig spoke Danish, followed Danish customs, and saw themselves as Danes. Henry IV, Count of Holstein-Rendsburg, protested and refused to accept the decision.

In 1425, war started again. In 1431, pro-German citizens opened the gates of Flensburg, and a German noble army marched in. In 1432, peace was made, and Eric recognized the lands the German nobles had taken.

In 1439, the new Danish king Christopher III bought the loyalty of count Adolphus VIII of Holstein-Rendsburg. He gave him the entire Duchy of Schleswig as a hereditary fief, but still under the Danish crown. When Christopher died eight years later, Adolphus helped his nephew Count Christian VII of Oldenburg get elected to the Danish throne.

When Adolphus died in 1459 without children, his family line in Holstein-Rendsburg ended. The nobles of Holstein did not want Schleswig and Holstein to be separated, as this would cause economic problems.

So, King Christian I of Denmark (Adolphus's nephew) was easily elected as both duke of Schleswig and count of Holstein-Rendsburg. In 1460, the nobles agreed to elect him to prevent the two provinces from separating. Christian I had to promise that Schleswig and Holstein-Rendsburg would remain united "forever undivided." This was the first time Holstein was passed down through the female line.

The Treaty of Ribe was a statement made by King Christian I of Denmark. It allowed him to become count of Holstein-Rendsburg and regain the Danish duchy of Schleswig. It also gave the nobility the right to rebel if the king broke the agreement. For Holstein-Rendsburg, the King of Denmark became its count but could not make it part of Denmark. It remained part of the Holy Roman Empire.

For Schleswig, which was a Danish fief, the arrangement seemed strange, as the Danish king became his own vassal. But the nobles saw this as a way to prevent too much Danish control and to keep Holstein from being divided. This agreement meant that Schleswig would not follow later Danish laws, though the old Danish law code remained in use there.

Finally, in 1472, the emperor confirmed Christian I's rule over Dithmarschen and elevated him from Count to Duke of Holstein. This made Holstein a direct part of the Empire. In the next hundred years, Schleswig and Holstein were often divided among heirs. Instead of making South Jutland part of Denmark, Christian preferred to keep both provinces united.

An important change was the slow introduction of German administrators in Schleswig. This led to a gradual German influence in southern Schleswig. This German influence didn't really take hold until the late 1700s.

Schleswig-Holstein soon had a better education system than Denmark and Norway. The German nobility in Schleswig and Holstein was large, and education provided many people for government jobs. In the 16th and 17th centuries, educated people from Schleswig-Holstein were hired for government positions in Norway and Denmark. This meant that Denmark's government became partly German in the centuries before the 1800s.

Early Modern Age

16th and 17th Centuries

The German influence in southern Schleswig became stronger after the Protestant Reformation. This was promoted by Duke Christian III in the duchies after he became co-ruling duke in 1523. After Christian became King of Denmark and Norway, he made Lutheranism the official religion in all his lands in 1537. The Duchy of Holstein adopted its first Lutheran Church rules in 1542.

With Lutheranism, the High German language was used in churches in Holstein and southern Schleswig. Even though many people there spoke Danish, North Frisian, or Low Saxon, High German started to replace these local languages.

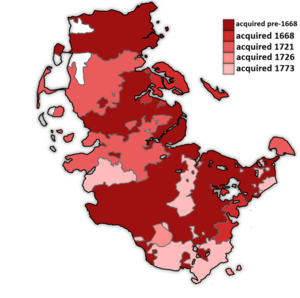

After Christian III secured his rule, he agreed to share power in the duchies with his younger half-brothers in 1544. Christian III, John II the Elder and Adolf divided the income from the Duchies of Holstein and Schleswig. They did this in a special way, assigning revenues from specific areas to each brother, while other taxes were collected together and then shared. This made the duchies look like a patchwork quilt, preventing them from becoming truly separate new duchies. The three rulers shared power. They also conquered Dithmarschen in 1559, dividing it into three parts.

Adolf, the third son, started the House of Holstein-Gottorp family line. This family's name comes from their palace at Gottorp. John II the Elder had no children, so his line ended. The Danish kings and the Dukes of Schleswig and Holstein at Gottorp ruled both duchies together.

In 1564, Christian III's youngest son, John the Younger, also received a share of the income from Holstein and Schleswig. His family line, the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg, did not share in the actual rule. They were only dukes in name. John the Younger's grandsons further divided this income.

When John II the Elder died in 1580, his share was split between Adolf and Frederick II, increasing the royal share. This complicated division of income tied both duchies together, despite their different legal ties to the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark. In 1640, the Schauenburg family line ended, and the County of Holstein-Pinneberg became part of the royal share of the Duchy of Holstein.

During the Thirty Years' War, relations between the Duke and the King got worse. In 1658, after the Danes invaded Swedish territory, the Duke worked with the Swedes. This almost destroyed the Danish Kingdom. Peace treaties stated that the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp was no longer a vassal of the Danish Crown in Schleswig. Frederick III, duke from 1616 to 1659, made it so that his oldest son would inherit everything. His full control over his Schleswig lands was confirmed by his son-in-law Charles X of Sweden in 1658 and later by the Treaty of Oliva. Denmark finally accepted this in 1689.

Christian Albert's son Frederick IV (died 1702) was again attacked by Denmark. But he had a strong supporter in King Charles XII of Sweden, who secured his rights in 1700. Frederick IV was killed in battle in 1702. In 1713, the regent broke the duchy's neutrality to help Sweden. Frederick IV of Denmark used this as an excuse to remove the duke by force. Holstein was returned to him by the Treaty of Frederiksborg in 1720. The next year, King Frederick IV was recognized as the sole ruler of Schleswig.

18th Century

After Sweden lost its influence on Holstein-Gottorp in 1713, Denmark could again control all of Schleswig. The Holstein-Gottorp dukes lost their lands in Schleswig but remained independent dukes in their part of Holstein. This was confirmed in the Treaty of Frederiksborg in 1720. The frustrated duke sought support from Russia and married into the Russian imperial family in 1725.

When her nephew, Duke Charles Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp, became Tsar Peter III of Russia, Holstein-Gottorp came under the rule of the Russian Emperor. This caused a conflict over land claims between Russia and Denmark.

Peter III threatened war with Denmark to get his family's lands back. But before any fighting started, his wife, Catherine II, took control of Russia. Empress Catherine changed Russia's position. She withdrew her husband's threat and even made an alliance with Denmark in 1765. In 1767, Catherine gave up Russia's claims in Schleswig-Holstein. This was confirmed by her son in 1773 with the Treaty of Tsarskoye Selo. Schleswig and Holstein were then united once more under the Danish king (Christian VII), who now received all of Holstein.

19th Century

When the Holy Roman Empire was abolished in 1806, Holstein became part of Denmark, though not officially. Under the Danish prime minister, many reforms were made in the duchies. For example, torture and serfdom (a system where people were tied to the land) were ended. Danish laws and money were introduced, and Danish became the official language for talking with Copenhagen.

The situation changed after 1806. While Schleswig stayed the same, Holstein and Lauenburg became part of the new German Confederation. This made the Schleswig-Holstein question unavoidable. Germans in Holstein, inspired by new national feelings, wanted to be treated as part of Germany. They were encouraged by Germans in Schleswig. But the Danes also had strong national feelings. This led to a crisis, made worse by the fact that the king had no male heirs for both the kingdom and the duchies.

The Duchy of Schleswig was originally part of Denmark. But in medieval times, it became a fief under the Kingdom of Denmark. Holstein was a fief of the Holy Roman Empire. Schleswig and Holstein have belonged to Denmark, the Holy Roman Empire, or been almost independent at different times. However, Schleswig was never part of the Holy Roman Empire or the German Confederation before 1864. For centuries, the King of Denmark was both a Danish Duke of Schleswig and a Duke of Holstein within the Holy Roman Empire. Since 1460, both were ruled by the Kings of Denmark. In 1721, all of Schleswig was united under the King of Denmark. European powers confirmed that future Danish kings would automatically become Duke of Schleswig.

The duchy of Schleswig was legally a Danish fief and not part of the Holy Roman Empire or the German Confederation. But the duchy of Holstein was a Holy Roman fief and a state of the German Confederation. The King of Denmark had a seat in the German Confederation because he was also Duke of Holstein and Duke of Lauenburg.

Schleswig-Holstein Question

The Schleswig-Holstein question was the name for all the complicated issues in the 19th century about how Schleswig and Holstein related to the Danish crown and the German Confederation.

From 1806 to 1815, Denmark claimed Schleswig and Holstein as part of its monarchy. This was not popular with the German population in Schleswig-Holstein. After the Napoleonic wars, a German national awakening led to a strong movement in Holstein and Southern Schleswig. They wanted to unite with a new Germany, which ended up being led by Prussia.

A big debate in the 19th century was about the old, unbreakable union of the two duchies. Danish National Liberals claimed Schleswig as part of Denmark. Germans claimed both Holstein (a German Confederation member) and Schleswig. The history of Schleswig and Holstein became very important in this political issue.

King Frederick VII of Denmark had no children, which helped the German unification movement. Also, the old Treaty of Ribe said the two duchies must never be separated. But a counter-movement grew among Danes in northern Schleswig and Denmark. They said Schleswig had been a Danish fief for centuries. They wanted the Eider River, the historic border, to mark the border between Denmark and Germany. Danish nationalists wanted to make Schleswig part of Denmark, separating it from Holstein. German unity supporters wanted to keep Schleswig linked to Holstein, taking Schleswig away from Denmark and into the German Confederation.

The Danish Succession

When Christian VIII became king in 1839, it was clear that the main male line of his family would soon end. The king's only son had no children. Since 1834, the question of who would inherit had been debated. Germans thought the solution was clear: the Danish crown could be inherited by women, but in Holstein, only men could inherit. So, if Christian VIII had no male heirs, the succession would go to the Dukes of Augustenburg.

Danes, however, wanted the king to declare that the monarchy was indivisible and would pass to a single heir. Christian VIII agreed to some extent in 1846. He said that the royal law of succession applied to Schleswig. But for Holstein, he couldn't make such a clear decision. The independence of Schleswig and its union with Holstein were clearly stated. An appeal by Holstein to the German Federal Assembly was ignored.

On January 28, Christian VIII announced a new constitution. It kept the local independence of different parts of the country but united them for common purposes. The duchies demanded that Schleswig-Holstein become a single state within the German Confederation.

First Schleswig War

In March 1848, these differences led to an uprising by German-minded assemblies in the duchies. They wanted independence from Denmark and closer ties with the German Confederation. Prussia sent its army to help the uprising, driving Danish troops from Schleswig and Holstein.

Frederick VII, who became king in January, said he had no right to deal with Schleswig this way. He gave in to the Danish party and announced a liberal constitution for Schleswig. Under this, Schleswig would keep its local independence but become part of Denmark.

A liberal constitution for Holstein was not seriously considered in Copenhagen. Holstein's politicians wanted the Danish constitution to be removed, not just in Schleswig but also in Denmark. They also demanded that Schleswig immediately join Holstein and become part of the German Confederation.

The rebels set up a temporary government in Kiel. The duke of Augustenburg went to Berlin to get help from Prussia. Prussia saw this as a chance to improve its image. So, Prussian troops marched into Holstein.

This war between Denmark and the duchies (with Prussia's help) lasted three years (1848–1850). It ended when the major European powers pressured Prussia to accept the London Convention of 1852. Under this agreement, the German Confederation returned Schleswig and Holstein to Denmark. Denmark promised not to tie Schleswig more closely to Denmark than to Holstein.

In 1848, King Frederick VII of Denmark promised a liberal constitution for Denmark. Danish nationalists wanted this constitution to apply to Danes (and Germans) in Schleswig. They also demanded protection for the Danish language in Schleswig, as German had become more dominant there.

Nationalists in Denmark wanted to make Schleswig (but not Holstein) part of Denmark.

On April 12, 1848, the German federal assembly recognized the temporary government of Schleswig. It ordered Prussia to enforce its decisions. The new temporary government respected the two main languages in Schleswig.

But the German movement and Prussia had not considered the European powers. These powers were against any breakup of Denmark. Even Austria, a German Confederation member, refused to help. Swedish troops helped the Danes. Nicholas I of Russia warned Prussia's king about the risks. Great Britain threatened to send its fleet to keep things as they were.

Frederick William ordered his troops to leave the duchies. The general refused, saying he was under the German Confederation's command. This led to negotiations breaking down. Prussia was caught between German demands and European threats.

On August 26, 1848, Prussia signed an agreement that mostly met Danish demands. Holstein appealed to the Frankfurt Parliament, which supported them. But it became clear that the temporary German government could not enforce its views, and the agreement was ratified.

This agreement was just a temporary truce. The main issues remained unsolved. In London, Denmark suggested separating Schleswig from Holstein, with Schleswig having its own constitution under the Danish crown. Great Britain and Russia supported this. On January 27, 1849, Prussia and the German Confederation accepted this. But negotiations failed because Denmark refused to give up the idea of an unbreakable union with the Danish crown. On February 23, the truce ended, and on April 3, the war restarted.

The principles Prussia was supposed to enforce were:

- That Schleswig and Holstein were independent states.

- That their union was unbreakable.

- That inheritance was only through the male line.

At this point, the tsar pushed for peace. Prussia decided to take matters into its own hands.

On July 10, 1849, another truce was signed. Schleswig was to be run separately under a mixed group. Holstein was to be governed by a representative of the German Confederation. A solution seemed far away. Danes in Schleswig still wanted female succession and union with Denmark. Germans wanted male succession and union with Holstein.

In 1849, the Constitution of Denmark was adopted. This made things more complicated. Many Danes wanted the new democratic constitution to apply to all Danes, including those in Schleswig. The constitutions of Holstein and Schleswig were controlled by the old Estates system, which gave more power to wealthy landowners, who were mostly German.

So, two government systems existed in the same state: democracy in Denmark, and the old Estates system in Schleswig and Holstein. The three parts were governed by one cabinet. This cabinet had liberal Danish ministers who wanted reforms and conservative Holstein ministers who opposed reforms. This stopped new laws from being made. Also, Danish opponents feared that Holstein's presence in the government and its membership in the German Confederation would lead to more German interference in Schleswig or even in Danish affairs.

In Copenhagen, the King and most of the government wanted to keep things as they were. Foreign powers like Great Britain, France, and Russia also supported this. They did not want a weaker Denmark or Prussia gaining Holstein (with its important naval harbor of Kiel and control of the Baltic entrance).

In April 1850, Prussia suggested a final peace based on returning to the situation before the war. Palmerston thought this was meaningless. The emperor Nicholas, angry with Prussia's weakness, intervened again. He saw the duke of Augustenburg as a rebel. Russia had guaranteed Schleswig to Denmark. If the Danish king couldn't deal with rebels in Holstein, Nicholas said he would intervene.

The threat was made stronger by the European situation. Austria and Prussia were almost at war. The only hope to stop Russia from helping Austria was to solve the Schleswig-Holstein question as Russia wanted.

After the First Schleswig War

A peace treaty was signed between Prussia and Denmark on July 2, 1850. Both sides kept their previous rights. Denmark was happy because the treaty allowed the King to restore his power in Holstein.

Danish troops then marched in to control the rebellious duchies. But while fighting continued, negotiations among the powers went on. On August 2, 1850, Great Britain, France, Russia, and Norway-Sweden signed an agreement. Austria later joined. They all agreed to restore the Danish monarchy's unity. The temporary Schleswig government was removed.

The Copenhagen government tried to reach an understanding with the people of the duchies in May 1851. On December 6, 1851, it announced a plan for the monarchy's future. This plan was based on equal states with a common government. On January 28, 1852, a royal letter announced a united state. This state would keep Denmark's basic constitution but give more power to the duchies' parliaments. Prussia, Austria, and the German Federal Assembly approved this. The question of who would inherit the throne was next. Only the Augustenburg succession issue made agreement impossible. On March 31, 1852, the duke of Augustenburg gave up his claim for money.

Another factor that hurt Danish interests was the rising power of German culture and conflicts with German states like Prussia and Austria. Schleswig and Holstein would surely become a battleground between Denmark, Prussia, and Austria.

The Danish government was worried because King Frederik VII was expected to have no son. Under Salic law (which some claimed applied to Holstein), the possible Crown Princess would have no legal right to Schleswig and Holstein. Danish citizens in Schleswig were afraid of being separated from Denmark. They protested against the German influence and demanded that Denmark declare Schleswig an integral part of Denmark. This angered German nationalists.

Holstein was part of the German Confederation. Annexing all of Schleswig and Holstein to Denmark would not be allowed by the Confederation. This gave Prussia a good reason to go to war with Denmark. Prussia could please nationalists by "freeing" Germans from Danish rule and enforce German Confederation law.

After Russia and others gave up their rights, Charlotte, sister of Christian VIII, and her son transferred their rights to his sister Louise. She, in turn, transferred them to her husband, Prince Christian of Glücksburg. On May 8, 1852, this arrangement was approved by major powers in London.

On July 31, 1853, Frederick VII of Denmark approved a law settling the crown on Prince Christian and his male heirs. The London agreement, while supporting Denmark's unity, stated that the German Confederation's rights in Holstein and Lauenburg would not be affected. It was a compromise and left the main issues unsolved. The German Federal Assembly was not in London, and German states saw the agreement as an insult. Danes were also not fully satisfied.

On February 15 and June 11, 1854, Frederick VII announced special constitutions for Schleswig and Holstein. These gave the local assemblies limited powers.

On July 26, 1854, Frederick published a common Danish constitution for the whole monarchy. In 1854, the Lutheran church bodies in Schleswig and Holstein became Lutheran dioceses, each led by a bishop.

On October 2, 1855, the common Danish constitution was replaced by a new parliamentary constitution. The two major German powers argued that this constitution was illegal because the duchies' assemblies had not been consulted. On February 11, 1858, the German Federal Assembly refused to accept its validity for Holstein and Lauenburg.

In the early 1860s, the "Schleswig-Holstein Question" became a big international debate again. But support for Denmark was decreasing. The Crimean War had weakened Russia. France was willing to give up support for Denmark in exchange for other benefits.

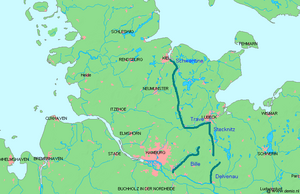

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert sympathized with the German side. But British ministers worried about Germany's growing naval power in the Baltic Sea. So, Great Britain sided with the Danes. There was also a complaint about tolls on ships passing through the Danish straits. To avoid this cost, Prussia planned the Kiel Canal, which couldn't be built as long as Denmark ruled Holstein.

The movement for separation continued in the 1850s and 1860s. Supporters of German unification increasingly wanted to include Holstein and Schleswig in a 'Greater Germany'. Holstein was completely German. Schleswig was mixed, with German, Danish, and North Frisian speakers. The population was mostly Danish, but many had switched to German since the 17th century. German culture was strong among the clergy and nobles, while Danish had a lower social status. For centuries, when the king had absolute power, these conditions caused few problems. But with democracy and national movements from around 1820, some people felt German, others Danish.

The medieval Treaty of Ribe had said Schleswig and Holstein were indivisible, though in a different context. When events in 1863 threatened to divide the duchies politically, Prussia had a good reason to go to war with Denmark. It could please nationalists by "freeing" Germans and enforce German Confederation law.

On July 29, 1853, in response to Denmark's claim that Schleswig was Danish territory, the German Federal Assembly (influenced by Bismarck) threatened German intervention.

On November 6, 1853, Frederik VII announced that the Danish constitution would no longer apply to Holstein and Lauenburg, but would remain for Denmark and Schleswig. Even this went against the idea of the duchies being indivisible. But the German Federal Assembly, busy at home, decided to wait until the Danish parliament tried to pass a law affecting the whole kingdom without consulting the duchies' assemblies.

In July 1860, this happened. In spring 1861, the assemblies were again fighting with the Danish government. The German Federal Assembly prepared for armed intervention. But it was not ready to act. Denmark, advised by Great Britain, decided to ignore it and talk directly with Prussia and Austria. These powers demanded the duchies be reunited, a matter beyond the Confederation's power. Denmark refused to let any foreign power interfere in its relations with Schleswig. Austria protested strongly against Denmark's actions.

Lord John Russell of Great Britain suggested a solution: the duchies would be independent under the Danish crown, with a budget agreed by all four assemblies, and a supreme council with Danes and Germans. Russia and the German powers accepted this. Denmark found itself alone in Europe. However, the international situation allowed Denmark to be bold. It rejected the powers' suggestions. Keeping Schleswig as part of Denmark was vital. The German Confederation had used the 1852 agreement to interfere in Denmark's internal affairs.

On March 30, 1863, a royal announcement was made in Copenhagen. It rejected the 1852 agreements. By defining Holstein's separate position, it denied German claims on Schleswig once and for all.

Three main groups had different goals:

- A German movement in the duchies dreamed of an independent Schleswig-Holstein with a liberal constitution. At first, they wanted a personal union with Denmark. Later, they called for an independent state ruled by the Augustenburg family. This group largely ignored that northern Schleswig was mostly Danish-minded.

- In Denmark, nationalists wanted a "Denmark to the Eider River". This meant making Schleswig part of Denmark again and ending German dominance there. This would also remove Holstein from the Danish monarchy, making liberal reforms easier. This group underestimated the German population in Southern Schleswig.

- A less vocal but more powerful group wanted to keep the Danish unitary state as it was: one kingdom and two duchies. This would avoid division but not solve the ethnic and constitutional problems. Most Danish officials and major powers like Russia, Britain, and France supported this.

- A fourth idea, that Schleswig and Holstein should both become provinces of Prussia, was hardly considered before the war of 1864. But this is what happened after the Austro-Prussian War two years later.

As the childless King Frederick VII grew older, Danish governments focused more on keeping control of Schleswig after his death. Both duchies were ruled by the kings of Denmark and had a long shared history. But their connection to Denmark was very complex. Holstein was part of the German Confederation. Denmark and Schleswig (as a Danish fief) were outside it. German nationalists claimed that the succession laws for the duchies were different from Denmark's. Danes said this only applied to Holstein, and Schleswig followed Danish succession law. Another complication was the 1460 Treaty of Ribe, which said Schleswig and Holstein should "be together and forever unseparated."

In 1863, King Frederick VII of Denmark died without an heir. According to the succession laws of Denmark and Schleswig, the crowns would go to Duke Christian of Glücksburg (the future King Christian IX). The crown of Holstein was more complicated. This decision was challenged by a rival pro-German branch of the Danish royal family, the House of Augustenburg. They claimed both Schleswig and Holstein, just like in 1848. This happened at a very important time, as a new constitution for Denmark and Schleswig had just been finished and was waiting for the king's signature. In the Duchy of Lauenburg, the personal union with Denmark ended, and its assemblies elected a new family in 1865.

The November Constitution

The new November Constitution would not directly annex Schleswig to Denmark. Instead, it would create a joint parliament to govern the shared affairs of Denmark and Schleswig. Both would keep their own parliaments. A similar attempt in 1855, including Holstein, had failed due to opposition from the people in Schleswig and German states. Most importantly, Article I clarified succession: "The form of government shall be that of a constitutional monarchy. The royal authority shall be inherited. The law of succession is specified in the law of succession of July 31, 1853, applying for the entire Danish monarchy."

Denmark's new king, Christian IX, was in a very difficult position. The first thing he had to do as king was sign the new constitution. Signing it would break the terms of the London Protocol, likely leading to war. Refusing to sign would make him unpopular with his Danish subjects, who supported his rule. He chose what seemed the lesser of two evils and signed the constitution on November 18.

The news was seen as a violation of the London Protocol, which banned such changes. It caused excitement and anger in German states. Frederick, Duke of Augustenburg, claimed his rights, saying he had not agreed to give them up. In Holstein, people supported him, and this spread to Schleswig when the new Danish constitution became known. German princes and people strongly supported his claim. Despite Austria and Prussia's negative stance, the federal assembly decided to occupy Holstein until the succession issue was settled.

Second Schleswig War

On December 24, 1863, troops from Saxony and Hanover marched into the German duchy of Holstein in the name of the German Confederation. With their support, the duke of Augustenburg took over the government as Duke Frederick VIII.

It was clear to Bismarck that Austria and Prussia, as parties to the London Protocol of 1852, had to uphold the succession as set by it. Any action they took against Denmark for violating the agreement had to be correct to avoid European interference. The new constitution signed by Christian IX was enough reason for them to act. Bismarck knew exactly what he wanted: to annex the duchies.

After Christian IX of Denmark made Schleswig (but not Holstein) part of Denmark in 1863, Bismarck convinced Austria to join the war. Other European powers and the German Confederation also agreed.

Protests from Great Britain and Russia against the German federal assembly's actions, along with a proposal from Saxony to recognize Duke Frederick's claims, helped Bismarck persuade Austria that immediate action was needed.

On December 28, Austria and Prussia proposed to the federal assembly that the Confederation occupy Schleswig. This would ensure Denmark followed the 1852 agreements. This implied recognizing Christian IX's rights, which was rejected. So, the federal assembly was told that Austria and Prussia would act as independent European powers.

On January 16, 1864, they signed an agreement. Bismarck made sure it stated that the two powers would decide together on the duchies' relations and would not decide the succession without mutual consent. Bismarck gave Denmark an ultimatum: abolish the November Constitution within 48 hours. The Danish government refused.

Austrian and Prussian forces crossed into Schleswig on February 1, 1864, and war became unavoidable. An invasion of Denmark itself was not originally planned. But on February 18, some Prussian soldiers crossed the border and occupied a village. Bismarck decided to use this to change the whole situation. He urged Austria to take strong action to settle not only the duchies' question but also the wider German Confederation issue. Austria reluctantly agreed to push the war.

On March 11, a new agreement was signed. It declared the 1852 agreements no longer valid. The position of the duchies within the Danish monarchy would be decided by friendly talks.

Meanwhile, Lord John Russell of Great Britain, supported by Russia, France, and Sweden, suggested a new European conference. The German powers agreed, but only if the 1852 agreements were not the basis and if the duchies were only personally tied to Denmark. But the conference, which started in London on April 25, only showed how complicated the issues were.

Prussia clearly aimed to acquire the duchies. The first step was to get the duchies recognized as absolutely independent. Austria could only oppose this by risking its influence among German states. So, the two powers agreed to demand the complete political independence of the duchies, united by common institutions. Prussia wanted to keep the annexation option open but made it clear that any solution must involve Schleswig-Holstein being fully under its military control. This worried Austria, which didn't want Prussia's power to grow further. Austria then started to support the duke of Augustenburg's claims.

Austria was hesitant to join a "war of liberation" because of its own problems with different nationalities. After Christian IX of Denmark made Schleswig part of Denmark in 1863, Bismarck convinced Austria to join the war.

On June 25, the London conference ended without a solution. On the 24th, Austria and Prussia made a new agreement: the war's goal was now the complete separation of the duchies from Denmark. As a result of the short campaign that followed, a peace treaty was signed on August 1. The king of Denmark gave up all his rights in the duchies to the emperor of Austria and the king of Prussia.

The final treaty was signed in Vienna on October 30, 1864. It allowed people in the duchies to choose Danish nationality within six years and move to Denmark, while keeping their land in the duchies.

This Second War of Schleswig in 1864 was presented by the invaders as enforcing German Confederation law. After losing the Battle of Dybbøl, the Danes could not defend Schleswig's borders. They had to retreat and were eventually pushed out of the entire Jutland peninsula. Denmark surrendered. Prussia and Austria took over the administration of Schleswig and Holstein, respectively, under the Gastein Convention of August 14, 1865.

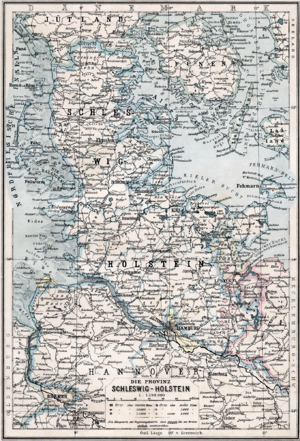

The northern border of Schleswig-Holstein from 1864 to 1920 was slightly different from the modern Danish county of Sønderjylland.

After the Second Schleswig War

Soon, disagreements arose between Prussia and Austria over how to run and what to do with the duchies. Bismarck used these disagreements to start the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Austria's defeat led to the end of the German Confederation and Austria's withdrawal from Holstein. Holstein, along with Schleswig, was then taken over by Prussia.

After the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, a part of the Peace of Prague treaty said that the people of Northern Schleswig should get to vote on whether they wanted to stay under Prussian rule or return to Danish rule. This promise was never kept by Prussia or later by united Germany.

Many people found the Schleswig-Holstein problem very difficult to solve. Lord Palmerston famously joked that only three people understood the Schleswig-Holstein question: one was dead, one had gone insane, and the third was himself, but he had forgotten it.

In the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Prussia took Holstein from Austria. It also took over Austria's German allies. The annexed states became provinces of Prussia. Holstein and Schleswig merged into the Province of Schleswig-Holstein. The Lutheran churches in Schleswig and Holstein merged into a new church in 1867.

Danes under German Rule

The situation of Danes in Schleswig after it was given to Prussia was set by two treaties: the Treaty of Vienna (October 30, 1864) and the Peace of Prague (August 23, 1866). Under the first treaty, Danish people living in the area could choose Danish nationality within six years. They could move themselves, their families, and their personal property to Denmark, while keeping their land in the duchies. About 50,000 Danes from North Schleswig chose Denmark and were expelled. The treaty also promised a vote for the people of North Schleswig to decide if they wanted to rejoin Denmark. This vote never happened. Prussia had no intention of giving up the land. The clause about the vote was officially removed in 1878.

Meanwhile, the Danes who had chosen Danish nationality and were expelled started to return to Schleswig. By doing so, they lost their Danish citizenship without gaining Prussian citizenship. This problem was passed on to their children. The Prussian courts decided that those who chose Danish citizenship lost their rights under the treaty.

So, in the border areas, many people were in a difficult situation. They had lost their Danish citizenship and could not get Prussian citizenship. Their exclusion from Prussian rights was also due to other reasons.

The Danes tried hard to keep their national traditions and language, despite many difficulties. The Germans wanted to absorb these Danes into the German empire. The uncertain status of the Danish "optants" (those who opted for Danish nationality) was a useful tool for this. Danish activists who were German citizens could not be touched if they followed the law. Pro-Danish newspapers run by German citizens were protected by the constitution.

But the situation for the optants was very different. These people faced home searches, arrests, and expulsions. When pro-Danish newspapers hired only German citizens as editors, the authorities targeted optant typesetters and printers. The Prussian police became very good at finding optants. Since optants lived among the general population, no home or business was safe from official checks.

For example, on April 27, 1896, a book was taken by authorities for using the historical term Sønderjylland (South Jutland) for Schleswig. To make things worse, the Danish government refused to let the expelled Danish optants settle in Denmark. This rule was changed in 1898 for children born after the law. This difficult situation ended only with a treaty between Prussia and Denmark on January 11, 1907.

This treaty allowed children born to Danish optants before 1898 to get Prussian nationality. The Danish government also agreed not to refuse residence to children of Schleswig optants who did not get Prussian nationality. This agreement seemed to end the Schleswig question. However, it only made the conflict between the two groups worse. Germans in the northern border areas felt betrayed.

For forty years, German influence, backed by the empire, had barely held its own in North Schleswig. Despite many people moving away, in 1905, 139,000 of the 148,000 people in North Schleswig spoke Danish. Even among German-speaking immigrants, more than a third spoke Danish in the first generation. But from 1864 onwards, German had slowly replaced Danish in churches, schools, and even playgrounds. The scattered German communities could not accept a situation that threatened their social and economic survival. Forty years of dominance had filled them with pride, and the question of the two nationalities in Schleswig remained a source of trouble within the German empire.

After 1888, German was the only language taught in schools in Schleswig.

20th Century

After World War I

After Germany lost World War I, in which Denmark was neutral, the winners offered Denmark a chance to redraw the border between Denmark and Germany. The government of Carl Theodor Zahle chose to hold the Schleswig Plebiscite to let the people of Schleswig decide which nation they belonged to. King Christian X of Denmark and some groups were against dividing Schleswig. The king dismissed Zahle's government, causing a political crisis called the Easter Crisis of 1920.

The Allied powers arranged a referendum in Northern and Central Schleswig. In Northern Schleswig on February 10, 1920, 75% voted to reunite with Denmark, and 25% voted for Germany. In Central Schleswig on March 14, 1920, the results were opposite: 80% voted for Germany and only 20% for Denmark. No vote happened in the southern third of Schleswig because the result for Germany was clear. On June 15, 1920, North Schleswig officially returned to Danish rule. Germany kept all of Holstein and South Schleswig, which remained part of the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein. The Danish-German border was the only border set after World War I that Hitler never challenged.

World War II

In the Second World War, after Nazi Germany occupied Denmark, some local Nazi leaders in Schleswig-Holstein wanted to restore the old border and take back the areas given to Denmark after the plebiscite. However, Hitler stopped this. His general policy was to cooperate with the Danish Government during the occupation and avoid direct conflicts with the Danes.

After World War II

After Germany lost World War II, there was again a chance that Denmark could get back some of its lost land in Schleswig. Although no land changes happened, it led to Prime Minister Knud Kristensen having to resign. This was because the parliament did not support his strong desire to make South Schleswig part of Denmark.

Today, there is still a Danish minority in Southern Schleswig and a German minority in Northern Schleswig.

After the expulsion of Germans after World War II, Schleswig-Holstein took in many German refugees. This caused the state's population to grow by 33% (860,000 people).

See also

- Danish names for places in Germany

- German exonyms for places in Denmark

- List of rulers of Schleswig-Holstein

In Spanish: Historia de Schleswig-Holstein para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Schleswig-Holstein para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |