History of Thessaloniki facts for kids

The history of Thessaloniki goes back to the time of the ancient Macedonians. Today, with open borders in Southeastern Europe, Thessaloniki is growing fast. It serves as a main port for northern Greece (the regions of Macedonia and Thrace) and for the whole of Southeastern Europe.

Contents

How Thessaloniki Began: The Hellenistic Era (around 315 BC)

The city was founded around 315 BC by King Cassander of Macedon. He built it near an old town called Therma and 26 other small villages. Cassander named the new city after his wife, Thessalonike. She was the half-sister of Alexander the Great.

Her name, "Thessalonike," means "victory of Thessalians." This name celebrated her birth on the day her father, Philip II, won a battle with help from horsemen from Thessaly. Thessaloniki grew quickly. By the 2nd century BC, it already had its first protective walls. The city also became a self-governing part of the Kingdom of Macedon. It had its own parliament, but the King could still get involved in its local matters.

The Roman Era (168 BC onwards)

After the Kingdom of Macedon fell in 168 BC, Thessaloniki became a city of the Roman Republic. It was called Thessalonica in Latin. The city became an important trading center because it was on the Via Egnatia. This was a major Roman road that connected Byzantium (later Constantinople) with Dyrrhachium (now Durrës in Albania). This road helped trade between Europe and Asia.

Thessaloniki became the capital of one of the four Roman regions of Macedonia. For a short time in the 1st century BC, it was even the capital for all the Greek provinces. The city kept its special rights but was ruled by a Roman official called a praetor. It also had a Roman army stationed there. Because trade was so important, the Romans built a large harbor called the Burrowed Harbour. This harbor was used for trade until the 18th century. Later, land was added to expand the port. You can still find parts of the old harbor's docks under Frangon Street today.

The city's acropolis, a fortified part on the northern hills, was built in 55 BC. This was for safety after Thracian groups raided the city's outer areas.

Early Christianity in Thessaloniki

Around 50 AD, Paul the Apostle visited Thessaloniki during his second missionary trip. He spoke to the Jews in the main synagogue for three Sabbaths. He shared Christian beliefs, and some Jews and Greeks, including important women, became Christians. However, some Jews did not want conflict and forced Paul and his friends, Silas and Timothy, to leave. They went to Veroia, also known as Berea, and had more success there. Paul later wrote two letters to the new church in Thessaloniki, probably between 51 and 53 AD. These are the First Epistle to the Thessalonians and the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians.

In 306 AD, Thessaloniki got its patron saint, St. Demetrius. Christians believed he performed many miracles to save the city. Demetrius was a Roman official who was killed in a Roman prison. Today, the Church of St. Demetrius stands where he died. The church was first built in 463 AD. Other important Roman buildings still standing include the Arch and Tomb of Galerius in the city center.

The Byzantine Era (Medieval/Post-Roman)

When the Roman Empire split into East and West in 379 AD, Thessaloniki became the capital of the new Prefecture of Illyricum (a smaller region). It was the second most important city after Constantinople. In 390 AD, there was a revolt against Emperor Theodosius I. His general, Butheric, and other officials were killed. In revenge, 7,000 to 15,000 citizens were killed in the city's hippodrome. This act led to Theodosius being temporarily excommunicated from the church.

After the Western Roman Empire fell, there were many barbarian invasions. A huge earthquake in 620 AD badly damaged the city, destroying the Roman Forum and other public buildings. Thessaloniki was attacked by Slavs in the 7th century, but they never managed to capture it.

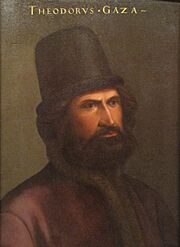

Important Figures and Events

The Byzantine brothers Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius were born in Thessaloniki. Emperor Michael III encouraged them to become missionaries in the northern regions. They used the South Slavonic language as the basis for the Old Church Slavonic language. In the 9th century, the Byzantines moved the market for Bulgarian goods from Constantinople to Thessaloniki. This made Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria invade and force the market back to Constantinople.

In 904 AD, Saracens (Arab pirates) led by Leo of Tripoli attacked and captured the city. After ten days of destruction, they left with 4,000 freed Muslim prisoners, 60 ships, a lot of treasure, and 22,000 slaves, mostly young people.

After these events, the city recovered. The Byzantines slowly regained power in the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries, bringing peace. A Jewish traveler named Benjamin of Tudela visited in the 12th century and noted a Jewish community of at least 500 people. During this time, the city held the fair of Saint Demetrius every October, just outside the city walls. It lasted six days.

The city's economy grew in the 12th century. Thessaloniki even had its own imperial mint. However, after Emperor Manuel I Komnenos died in 1180, the Byzantine Empire began to decline. In 1185, Normans from Sicily attacked and occupied the city, causing much damage. But their rule lasted less than a year.

Thessaloniki left Byzantine control in 1204 when Constantinople was captured by the Fourth Crusade. Thessaloniki and the land around it became the Kingdom of Thessalonica, the largest part of the Latin Empire in Greece. In 1224, Theodore Komnenos Doukas, a Greek ruler, took the city back and created the Empire of Thessalonica. Later, in 1246, the city became part of the Empire of Nicaea.

Despite invasions, Thessaloniki had a large population and busy trade. This led to great intellectual and artistic work. Many churches and frescoes from this time still exist. Scholars like Thomas Magististos taught there. Examples of Byzantine art can be seen in the mosaics of churches like Hagia Sophia and Saint George.

In the 14th century, the city faced a social movement called the Zealots (1342–1349). This started from a religious conflict but quickly became a political movement against the rich during a civil war. The Zealots ruled the city from 1342 to 1349.

The Ottoman Era (1430-1912)

The Byzantine Empire could not defend Thessaloniki against the advancing Ottoman Empire. So, in 1423, they gave the city to the Republic of Venice. Venice held the city until the Ottoman Sultan Murad II captured it on March 29, 1430, after a three-day siege. The Ottomans had captured Thessaloniki before in 1387, but lost it in 1402 after a defeat by Tamerlane.

During Ottoman rule, the city's Muslim and Jewish populations grew. By 1478, Thessaloniki had more Muslims than Greek Orthodox people. Around 1500, Sephardic Jews began arriving from Spain. They were forced to leave Spain by the Catholic King and Queen. The Ottoman Emperor invited Jews to settle in his lands, including Thessaloniki. By 1519, Jews made up 54% of the city's population. Sephardic Jews, Muslims, and Greek Orthodox people remained the main groups for the next 400 years.

Thessaloniki became the largest Jewish city in the world and stayed that way for at least 200 years. It was often called "Mother of Israel." At the start of the 20th century, about 60,000 of its 130,000 inhabitants were Sephardic Jews.

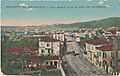

With new cultures arriving, Thessaloniki, called Selânik in Turkish, became one of the most important cities in the Ottoman Empire. It was the main trade center in the Balkans. A railway reached the city in 1888, and new modern port facilities were built between 1896 and 1904. The founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was born there in 1881. The Young Turk movement was also based in the city in the early 20th century.

Many Ottoman buildings can still be found in the city's Ano Poli (Upper Town) district. These include traditional wooden houses and fountains. In the city center, some stone mosques survived, like the Hamza Bey Mosque and the Aladja Imaret Mosque. The Bezesten (a covered market) and Yahudi Hamam (a bathhouse) also remain. Most of the more than 40 minarets were torn down after 1912 or fell during the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917. The only one left is at the Rotonda.

After the Greek War of Independence began, a revolt also happened in Macedonia. In May 1821, the governor of Thessaloniki ordered the killing of any Greeks found in the streets. It took until the end of the 19th century for the Greek community to recover.

From 1870, the city's population grew by 70%, reaching 135,000 in 1917. During the 19th century, Thessaloniki became a cultural and political center for the Bulgarian revival movement in Macedonia. In 1880, a Bulgarian Men's High School was founded. Later, a revolutionary group called the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) was formed here.

Balkan Wars and World War I (1912-1918)

During the First Balkan War, the Ottoman army in Thessaloniki surrendered to the Greek Army on November 9, 1912. This was a day after the feast of Saint Demetrios, the city's patron saint. This date is now celebrated as the city's liberation anniversary. The next day, Bulgarian troops were allowed to enter the city in small numbers.

The final status of the city was uncertain for a while. Some suggested making it a neutral, international city. But the Greeks felt a strong connection to Thessaloniki. This feeling grew when King George I of Greece was assassinated there on March 18, 1913. After Greece and Serbia won the Second Balkan War, the Treaty of Bucharest on August 10, 1913, officially made Thessaloniki part of Greece.

In 1915, during World War I, a large Allied army landed in Thessaloniki. They used the city as a base to fight against Bulgaria. This led to a political conflict in Greece between the pro-Allied Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos, and the pro-neutral King Constantine. In 1916, pro-Venizelist army officers, with Allied support, started an uprising. This led to a temporary government, led by Venizelos, that controlled northern Greece. Since then, Thessaloniki has been called symprotévousa ("co-capital").

The Great Fire of 1917

On August 18, 1917, the city faced a terrible event. Most of Thessaloniki was destroyed by a single fire. It was accidentally started by French soldiers. The fire left about 72,000 people homeless, many of them Jewish. Venizelos did not allow the city center to be rebuilt until a modern city plan was ready. French architect Ernest Hebrard created this plan a few years later. The Hebrard plan changed Thessaloniki from an oriental-looking city into the modern European city it is today.

The great fire destroyed almost half of the city's Jewish homes and businesses. This led to many Jews leaving the city. Many went to Palestine, others to Paris, and some to the United States. However, their numbers were quickly replaced by many Greek refugees from Asia Minor. This happened because of a population exchange between Greece and Turkey after the Greco-Turkish War. With these new refugees, the city grew hugely and quickly. These events earned the city nicknames like "The Refugee Capital" and "Mother of the Poor."

World War II and Beyond

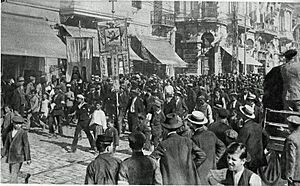

In May 1936, a large strike by tobacco workers led to chaos in the city. Ioannis Metaxas, who would later become a dictator, ordered the strike to be stopped. These events inspired the poet Yiannis Ritsos to write Epitafios.

Thessaloniki fell to Nazi Germany on April 22, 1941. It remained under German control until October 30, 1944. The city was heavily damaged by Allied bombing. Sadly, almost all of its Jewish population that remained after the 1917 fire was killed by the Nazis. Barely a thousand Jews survived.

Thessaloniki was rebuilt and recovered quickly after the war. Its population grew fast, and new buildings and industries developed throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. However, much of this growth happened without a full plan, which caused traffic and zoning problems that still exist today.

The Modern Era

On June 20, 1978, a strong earthquake hit the city. It measured 6.5 on the moment magnitude scale. The earthquake caused significant damage to buildings and even some Byzantine monuments. Forty people died when an apartment building collapsed. However, the large city recovered quickly from the disaster.

The early Christian and Byzantine monuments of Thessaloniki were added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1988. Thessaloniki later became the European Capital of Culture in 1997.

Today, Thessaloniki is one of the most important trade and business centers in the Balkans. Its port, the Port of Thessaloniki, is one of the largest in the Aegean Sea. It helps trade throughout the Balkan region. The city is also one of the largest student centers in Southeastern Europe and has the biggest student population in Greece. It has two state universities: the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the largest university in Greece (founded in 1926), and the University of Macedonia.

In June 2003, the city hosted a meeting of European leaders at the end of Greece's time as head of the EU. In 2004, Thessaloniki hosted some of the football events for the 2004 Summer Olympics. This led to a huge modernization program for the city.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Salónica para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Salónica para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |