History of the Kurds facts for kids

The Kurds are an ethnic group from the Middle East. They have lived for a long time in the mountains south of Lake Van and Lake Urmia. This area is often called Kurdistan. Most Kurds speak Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji Kurdish) or Central Kurdish (Sorani).

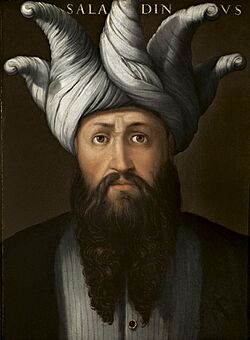

Historians have different ideas about where the Kurds came from. Some think they are related to ancient groups like the Carduchoi. The first known Kurdish leaders under Islamic rule lived between the 10th and 12th centuries. These included the Hasanwayhids and the Ayyubid dynasty, which was started by Saladin. A big moment in Kurdish history was the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514. This battle led to an alliance between Kurds and the Ottoman Turks. The book Sharafnama, written in 1597, is the first history of the Kurds. In the 20th century, many Kurds wanted their own independent state, as planned by the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. Some areas, like Iraqi Kurdistan, gained some self-rule. However, in Turkish Kurdistan, there was a long conflict from 1984 to 1999, and the region still faces challenges.

Contents

What Does "Kurd" Mean?

There are different ideas about where the name Kurd comes from. One idea is that it comes from an old Persian word, kwrt-, which meant "nomad" or "tent-dweller." After the Muslim conquest of Persia, this word was used in Arabic for nomadic tribes.

Another idea is that the name Kurd comes from an ancient place name near the Tigris River. An English expert, Godfrey Rolles Driver, thought it was linked to the Sumerian word Karda from ancient clay tablets. He believed that similar words like Cordueni and Karduchi all referred to the same people.

Some also think "Kurd" might come from an old Bronze Age name, Qardu. This name might also be linked to the Arabic name Ǧūdī. This name continued in ancient times as part of Corduene. Its people, the Carduchoi, were mentioned by Xenophon in the 4th century BC. They fought against the Greek army retreating through the mountains. Some experts agree that Corduene was an early Kurdish region. However, other scholars disagree.

By the 16th century, the term Kurd started to mean an ethnic group. This was true even if they spoke different languages. Sherefxan Bidlisi, a writer from the 16th century, said there were four main groups of "Kurds": Kurmanj, Lur, Kalhor, and Guran. Each spoke a different dialect or language.

Early Kurdish History

The Kurdish language belongs to the Northwestern Iranian language group. It likely separated from other languages around the early centuries AD. Kurdish itself developed as a group within Northwest Iranian during the Middle Ages (from about the 10th to 16th centuries).

Many believe the Kurdish people have mixed origins. They may come from both Iranian-speaking and non-Iranian groups. These include earlier tribes like the Lullubi, Guti, Cyrtians, and Carduchi.

One popular idea about where the Kurds first lived comes from D.N. Mackenzie in the 1960s. He thought that the ancestors of Kurds, Persians, and Baloch people lived together in central Iran. He suggested that the Proto-Kurds lived in northwestern Luristan or Isfahan.

Early Kurdish Kingdoms

In the late 10th century, there were five Kurdish kingdoms. These included the Shaddadids in Armenia, the Rawadids in Tabriz, the Hasanwayhids in the East, the Annazids in Kermanshah, and the Marwanids in Diyarbakır.

Later, in the 12th century, the Kurdish Hazaraspid dynasty ruled in the southern Zagros mountains. They took over areas like Kuhgiluya and Khuzestan.

Around 1150, Ahmad Sanjar, a powerful Seljuq ruler, created a province called Kurdistan. Its capital was Bahar, near ancient Ecbatana (Hamadan). This province included areas like Sinjar, Shahrazur, Hamadan, Dinawar, and Kermanshah. A unique culture grew around Dinawar.

Marco Polo, a famous traveler, met Kurds in Mosul in the 13th century. He wrote about Kurdistan and the Kurds for people in Europe.

Ayyubid Period

One of the most powerful times for Kurds was in the 12th century. This was when Saladin founded the Ayyubid dynasty. Saladin was from a Kurdish tribe. His dynasty ruled lands from the Kurdish regions all the way to Egypt and Yemen.

Kurdish Kingdoms (16th to 19th Century)

Kurds created several independent states or kingdoms. These included Ardalan, Badinan, Baban, Soran, Hakkari, and Badlis. A detailed history of these states is in the Sharafnama by Prince Sharaf al-Din Biltisi (1597).

The most important of these was Ardalan, founded in the early 14th century. Ardalan controlled areas like Zardiawa, Khanaqin, Kirkuk, and Hawraman. Its capital was first in Sharazour, then moved to Sinne (in Iran). The Ardalan Dynasty ruled as vassals until the Qajar dynasty ended their rule in 1867.

Kurdish Neighborhoods

In the Middle Ages, many cities outside Kurdistan had Kurdish neighborhoods. These were formed as Kurdish tribes and scholars moved there. In these neighborhoods, Kurds often had their own mosques and schools.

- In Aleppo, there was Haret al-Akrad.

- In Baghdad, Darb al-Kurd was recorded since the 11th century.

- In Cairo, Haret al-Akrad was at al-Maqs.

- In Damascus, there were Kurdish areas like Mount Qasyun. Kurdish leaders built mosques and schools. There was also a Kurdish cemetery.

- In Gaza, Shuja'iyya was named after a Kurd who died in 1239.

- In Hebron, Haret al-Akrad was linked to the Ayyubid conquests.

- In Jerusalem, Haret al-Akrad was later called Haret esh-Sharaf. The city also had a school built by a Kurdish leader in 1294.

Safavid Period

For many centuries, starting in the early modern period, the Kurds were caught between two powerful empires: the Sunni Ottoman Empire and the Shia Safavid Empire. Ismail I, the Safavid Shah, ruled over all Kurdish areas. From 1506 to 1510, Yazidis revolted against Ismail I. Their leader was defeated, and many Kurdish prisoners were killed.

In the mid-17th century, Kurds on the western borders had firearms. However, many Kurds still preferred to fight with lances and swords. They thought using a gun was not manly.

Moving the Kurds

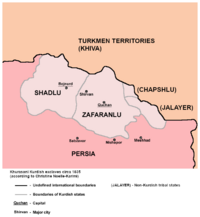

The Safavids moved hundreds of thousands of Kurds from their borders with the Ottomans. This was to protect their borders. Other groups like Armenians and Georgians were also moved. As the borders changed, many Kurdish regions in Anatolia faced destruction and forced movement. This started under Shah Tahmasp I (ruled 1524–1576). He used a "scorched earth" policy, destroying cities and farms. He forced people into Azerbaijan, then moved them nearly 1,600 km (1,000 miles) east to Khorasan.

Shah Abbas I also moved many Kurds from the Zagros Mountains and Caucasus Mountains. He wanted to prevent them from helping the Ottomans. He made it attractive for Kurds to join the army, creating an army of tens of thousands of Kurdish soldiers. Abbas also destroyed villages and moved people into the heartland of Persia.

Safavid historians wrote about these forced movements. One historian described how Shah Abbas destroyed the land north of the Araxes river and west of Urmia. He rounded up the people and moved them away from danger. Any resistance was met with massacres. Houses, churches, mosques, and crops were all destroyed. Many Kurds ended up in Greater Khorasan, and others were scattered across Iran. These groups formed new Kurdish communities outside Kurdistan.

Battle of Dimdim

There is a famous historical story about a long battle in 1609–1610 between Kurds and the Safavid Empire. It happened around a fortress called "Dimdim" near Lake Urmia in northwestern Iran. In 1609, the ruler of Beradost, "Emîr Xan Lepzêrîn", rebuilt the ruined fortress. He wanted his principality to stay independent from the Ottomans and Safavids.

The Safavids saw this as a threat. Many Kurds joined Amir Khan. After a long and bloody siege, Dimdim was captured. All the defenders were killed. Shah Abbas ordered a general massacre in Beradost and Mukriyan. He then moved the Turkish Afshar tribe into the region and deported many Kurdish tribes to Greater Khorasan.

Persian historians saw this battle as a Kurdish rebellion. But in Kurdish stories and histories, it was a fight for freedom against foreign rule. The story of Dimdim is considered a national epic for Kurds.

Ottoman Period

When Sultan Selim I defeated Shah Ismail I in 1514, he took over Western Armenia and Kurdistan. He asked Idris, a Kurdish historian from Bitlis, to organize the new lands. Idris divided the territory into districts and let local Kurdish chiefs remain as governors. He also resettled Kurds from Hakkari and Bohtan into the rich lands between Erzerum and Yerevan.

Janpulat Revolt

The Janpulat clan were Kurdish lords in the Aleppo region. Their leader, Hussein Janpulatoğlu, became governor of Aleppo in 1604. But he was executed by the Ottomans. His nephew, Ali Janbulad, revolted in revenge in 1606. He was supported by the Duke of Tuscany. Ali Janbulad conquered a large area with 30,000 troops. The Ottoman Grand Vizier, Murad Pasha, fought against him in 1607. Ali Pasha escaped and was later pardoned. He became a governor in Hungary but was executed in 1610.

Rozhiki Revolt

In 1655, Abdal Khan, the Kurdish ruler of Bidlis, formed his own army. He fought a big war against the Ottoman troops. Many Yazidis were in his army. The main reason for this revolt was a disagreement between Abdal Khan and Melek Ahmad Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Diyarbakır.

Ottoman troops marched on Bidlis and harmed civilians. Abdal Khan had built strong defenses around Bitlis. The Ottomans attacked and defeated the Rozhiki soldiers. They then looted Bidlis. Abdal Khan tried to assassinate Melek Ahmad Pasha but failed. After Bidlis fell, 1,400 Kurds kept fighting from the city's old castle. Most surrendered and were pardoned, but 300 were killed by Melek Ahmad.

Bedr Khan of Botan

The system of rule set up by Idris stayed mostly the same until the Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829. But the Kurds grew more powerful. They spread westward as far as Ankara.

After the war with Russia, the Kurds tried to break free from Ottoman control. This led to the Bedr Khan clan uprising in 1834. The Ottomans decided to end the self-governing regions in the East. They put strong garrisons in towns and replaced many Kurdish chiefs with Turkish governors. A revolt led by Bedr Khan Bey in 1843 was stopped. After the Crimean War, the Turks strengthened their control.

In the 1830s, Bedr Khan was defeated by the Assyrians of Hakkari. The Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II's efforts to modernize angered Kurdish chiefs. So, two powerful Kurdish families rebelled in 1830. Bedr Khan of Botan rose up in western Kurdistan, and Muhammad Pasha of Rawanduz rebelled in the east. He took control of Mosul and Erbil.

At this time, Turkish troops were busy fighting in Syria. So, they could not stop the revolt. As a result, Bedr Khan expanded his power. He created a Kurdish principality until 1845. He even made his own coins. In 1847, the Turkish forces defeated Bedr Khan and sent him away to Crete. He later returned to Damascus and died there in 1868. Bedr Khan Beg also attacked Assyrian Christians in Hakkari in 1843 and 1846. He killed up to 4,000 Assyrians.

Bedr Khan became king after his brother died. His nephew was very angry about this. The Turks used this to trick the nephew into fighting his uncle. They promised to make him king if he killed Bedr Khan. The nephew brought many Kurdish warriors to attack his uncle. After defeating Bedr Khan, the nephew was executed instead of becoming king. There are two famous Kurdish songs about this battle. After this, there were more revolts in 1850 and 1852.

Kurdistan existed as an official area for a short time, from 1847 to 1864. Its capital moved several times. In 1864, the province of Kurdistan was ended. Instead, the old provinces of Diyarbakir and Van were brought back. Around 1880, Shaikh Ubaidullah led a revolt to rule the areas between Lakes Van and Urmia. But Ottoman and Qajar forces defeated the revolt.

Shaikh Ubaidullah's Revolt and Armenians

After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, Sheikh Ubeydullah led an uprising in 1880–1881. He wanted to create an independent Kurdish state under Turkey's protection. The Ottoman government first supported this idea. They saw it as a way to counter plans for an Armenian state. But after Ubeydullah raided Persia, the government took back control. Before the 1877–1878 war, Kurds and Armenians generally got along well.

In 1891, the Ottomans strengthened the Kurds by creating a group of Kurdish cavalry called Hamidieh soldiers. These were well-armed. Small problems kept happening. Soon after, there was a massacre of Armenians in Sasun by Kurdish nomads and Ottoman troops.

20th Century History

Rise of Kurdish Identity

Kurdish nationalism, a strong sense of Kurdish identity, grew in the late 19th century. This was around the same time that Turks and Arabs also started to feel a stronger ethnic identity. Revolts happened now and then. But only in 1880, with the uprising led by Sheikh Ubeydullah, did Kurds start making demands as an ethnic group or nation. The Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II tried to bring prominent Kurdish leaders into his government to keep them loyal. This seemed to work, as Kurdish Hamidiye regiments were loyal during World War I.

The Kurdish nationalist movement after World War I was a reaction to changes in Turkey. Kurds, who were mostly Muslim, disliked the new government's focus on non-religious ideas. They also disliked the government taking more power, which threatened local Kurdish leaders. The strong Turkish nationalism in the new Turkish Republic also made Kurds feel left out.

Western powers, especially the United Kingdom, fighting the Turks, promised Kurds they would help them get independence. But they later broke this promise. An organization called the Kurdish Teali Cemiyet (Society for the Rise of Kurdistan) was important in shaping a Kurdish identity. It used a time of political freedom in Turkey (1908–1920) to turn interest in Kurdish culture and language into a political movement based on ethnicity.

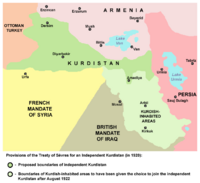

After World War I

Some Kurdish groups wanted self-rule. The Treaty of Sèvres after World War I planned for an independent Kurdish state in 1920. But Mustafa Kemal Atatürk prevented this. The later Treaty of Lausanne (1923) did not even mention Kurds. Turkey stopped Kurdish revolts in 1925, 1930, and 1937–1938. Iran did the same in the 1920s.

From 1922 to 1924, a Kingdom of Kurdistan existed in Iraq. When Iraqi leaders stopped Kurdish nationalist goals, war broke out in the 1960s. In 1970, Kurds refused limited self-rule in Iraq. They wanted larger areas, including the oil-rich Kirkuk region.

In 1922, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk referred to the region as "Kurdistan" three times. He gave a commander full power to support local Kurdish governments. This was based on the idea of self-determination for people in areas where Kurds lived.

In 1931, an Iraqi Kurdish statesman, Mihemed Emîn Zekî, described the borders of Turkish Kurdistan. These borders were similar to those drawn by the Ottomans. In 1932, Garo Sassouni defined the borders of "Kurdistan proper."

During the 1920s and 1930s, several large Kurdish revolts happened in Turkey. The most important were the Sheikh Said Rebellion (1925), the Ararat Revolt (1930), and the Dersim Revolt (1938). After these revolts, Turkish Kurdistan was put under military rule. Many Kurds were forced to move. The government also encouraged Albanians and Assyrians to move into the region. These events created a long-lasting distrust between Turkey and the Kurds.

From 1937 to 1944, Soviet Kurds were forced to move from Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia.

World War II

During World War II, Kurds formed 10 companies in the Iraq Levies. These were British-recruited forces in Iraq. Kurds helped the British defeat a pro-Nazi coup in Iraq in 1941. A quarter of the 1st Parachute Company of the Iraq Levies was Kurdish. This company fought in Albania, Italy, Greece, and Cyprus.

Kurds also took part in the Soviet occupation of northern Iran in 1941. This created the Persian Corridor, which was important for supplying the USSR. This led to the short-lived Kurdish Republic of Mahabad.

Even though they were a small group in the Soviet Union, Kurds played a big role in the Soviet war effort. Many Kurds served in major battles like Smolensk, Sevastopol, Leningrad, and Stalingrad. They also joined partisan groups fighting behind German lines. Kurds took part in the advance into Hungary and the invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria.

After World War II

Turkey

About half of all Kurds live in Turkey. They make up about 18 percent of Turkey's population. Most live in the southeastern part of the country.

Around five million people in Turkey spoke Kurdish in 1980. The ban on using the Kurdish language in Turkey was only lifted in 1991. It is still restricted in most official places, including schools. The number of Kurdish speakers is less than the 15 million people who identify as ethnic Kurds.

From 1915 to 1918, Kurds tried to end Ottoman rule. They were encouraged by Woodrow Wilson's support for non-Turkish groups. They asked for independence at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. The Treaty of Sèvres planned for an independent Kurdish state in 1920. But the later Treaty of Lausanne (1923) did not mention Kurds.

After the Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk created a Reform Council for the East. This council suggested creating Inspectorates-Generals in Kurdish areas. These areas were under military law, and Kurdish leaders were moved to western Turkey. These Inspectorates Generals were ended in 1952.

In the 1950s, Kurds gained political positions and tried to work within the Turkish Republic. But this was stopped by the 1960 Turkish coup d'état. In the 1970s, Kurdish nationalism changed. New Kurdish nationalists were influenced by Marxist ideas. They formed the militant PKK.

After these events, Turkey officially denied the existence of Kurds. Any expression of Kurdish identity was strongly stopped. Until 1991, using the Kurdish language was illegal. Now, Kurdish music, radio, and TV are allowed, but with strict time limits. Education in Kurdish is allowed only in private schools.

As late as 1994, Leyla Zana, the first female Kurdish representative in the Turkish Parliament, was charged with "separatist speeches." She was sentenced to 15 years in prison. She identified herself as a Kurd during her oath.

The PKK is a Kurdish organization that has fought against the Turkish state. They seek cultural and political rights and self-determination for Kurds. Turkey and its allies see the PKK as a terrorist organization.

From 1984 to 1999, the PKK and the Turkish military fought openly. Many villages in the southeast were emptied. Kurdish civilians moved to cities like Diyarbakır and Van, or to western Turkey and Europe. This displacement was caused by PKK actions, poverty, and Turkish military operations. Human Rights Watch has reported many cases where the Turkish military destroyed homes and villages. About 3,000 Kurdish villages in Turkey were destroyed, displacing over 378,000 people.

Nelson Mandela refused to accept the Atatürk International Peace Prize in 1992 because of the oppression of Kurds. He later accepted the award in 1999.

Iraq

Kurds make up about 17% of Iraq's population. They are the majority in at least three provinces in Northern Iraq, known as Iraqi Kurdistan. Many Kurds also live in Baghdad, Mosul, and other parts of Southern Iraq.

Kurds, led by Mustafa Barzani, fought against Iraqi governments from 1960 to 1975. In March 1970, Iraq offered a peace plan for Kurdish self-rule. But at the same time, Iraq started moving Arabs into the oil-rich regions of Kirkuk and Khanaqin. The peace agreement did not last. In 1974, the Iraqi government attacked the Kurds again. In 1975, Iraq and Iran signed an agreement, and Iran stopped supporting Iraqi Kurds. Iraq then moved more Arabs to the oil fields in northern Iraq. Between 1975 and 1978, 200,000 Kurds were sent to other parts of Iraq.

During the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s, the Iraqi government had anti-Kurdish policies. A civil war broke out. Iraq was criticized internationally for its harsh actions. These included mass killings of civilians, destroying thousands of villages, and deporting thousands of Kurds. The Iraqi government's campaign against Kurds in 1988 was called Anfal. The Anfal attacks destroyed two thousand villages and killed between 50,000 and 100,000 Kurds.

After the Kurdish uprising in 1991, Iraqi troops took back Kurdish areas. Hundreds of thousands of Kurds fled to the borders. To help, a "safe haven" was created by the United Nations. The self-governing Kurdish area was mainly controlled by two rival parties, the PUK and KDP. Kurds welcomed American troops in 2003 with celebrations. The area controlled by Kurdish fighters (peshmerga) expanded. Kurds gained control in Kirkuk and parts of Mosul. By early 2006, the two Kurdish areas merged into one unified region. Referendums were planned for 2007 to decide the final borders of the Kurdish region.

In June 2010, the PKK announced an end to a ceasefire. This was followed by Turkish air attacks on border villages.

On July 11, 2014, Kurdish forces took control of the Bai Hassan and Kirkuk oilfields. Baghdad condemned this and threatened "dire consequences." The 2017 Kurdistan Region independence referendum happened on September 25, with 92.73% voting for independence. This led to a military operation where the Iraqi government retook Kirkuk and forced the Kurdish government to cancel the referendum.

Iran

The Kurdish region of Iran has been part of the country for a very long time. Most of Kurdistan was part of the Iranian Empire until its western part was lost in wars against the Ottoman Empire. After the Ottoman Empire ended, Iran asked for Turkish Kurdistan and Mosul at the Paris Conferences in 1919. But these requests were rejected. Instead, the Kurdish area was divided among modern Turkey, Syria, and Iraq.

Today, Kurds live mostly in northwestern Iran and also in parts of Khorasan. They make up about 7–10% of Iran's population. Unlike in other countries with Kurdish populations, there are strong cultural and historical ties between Kurds and other Iranian peoples. Some modern Iranian ruling families, like the Safavids and Zands, are thought to have some Kurdish background. Kurdish literature has developed within Iran, influenced by the Persian language. Because of this shared history and culture, many Kurdish leaders in Iran do not want a separate Kurdish state.

The Iranian government has always been against any idea of independence for Iranian Kurds. During and after World War I, the Iranian government was weak. Several Kurdish tribal chiefs gained local power. At the same time, a wave of nationalism from the Ottoman Empire influenced some Kurdish chiefs near the border. Before this, identity in both countries was mostly based on religion. In 19th-century Iran, there was often tension between Shia and Sunni Muslims. Sunni Kurds were sometimes seen as helping the Ottomans.

In the late 1910s and early 1920s, a tribal revolt led by Kurdish chief Simko Shikak swept across Iranian Kurdistan. While some Kurdish nationalist ideas were present, historians agree they were not the main reason for Simko's movement. He relied more on traditional tribal motives. His fighters also attacked Kurdish people, not just government forces. They did not seem to feel a strong sense of unity with other Kurds.

Kurdish revolts and seasonal movements in the late 1920s, along with tensions between Iran and Turkey, led to border clashes. Both Iran and Turkey used Kurdish tribes for their own political goals. Turkey helped anti-Iranian Kurdish rebels, while Iran helped Kurdish rebels against Turkey. The Iranian government's forced efforts to make tribes settle down in the 1920s and 1930s led to many tribal revolts. For Kurds, these policies partly caused some tribes to rebel.

In response to growing Pan-Turkism and Pan-Arabism, which threatened Iran's borders, an Iranian nationalist idea called Pan-Iranism developed in the 1920s. Some groups openly supported Iranian help for Kurdish opposition against Turkey. The Pahlavi dynasty supported Iranian nationalism, which saw Kurds as an important part of the Iranian nation. Another important idea during this time was Marxism, which grew among Kurds due to the influence of the USSR.

This led to the Iran crisis of 1946. Kurdish and communist groups tried to gain self-rule and set up a Soviet-backed government called the Republic of Mahabad. This state was very small and could not include southern Iranian Kurdistan. It also failed to attract tribes outside Mahabad. So, when the Soviets left Iran in December 1946, government forces easily entered Mahabad as the tribes turned against the republic.

Several Marxist revolts continued for decades (1967, 1979, 1989–96). These were led by the KDP-I and Komalah. But these groups never pushed for a separate Kurdish country like the PKK in Turkey. Still, many leaders, like Qazi Muhammad, were killed. During the Iran–Iraq War, Iran supported Iraqi-based Kurdish groups and took in 1,400,000 Iraqi refugees, mostly Kurds.

Although Kurdish Marxist groups have lost influence in Iran since the Soviet Union ended, a new uprising started in 2004 by PJAK. This is a separatist group linked to the Turkey-based PKK. Iran, Turkey, and the United States consider PJAK a terrorist organization. Some experts say PJAK is not a serious threat to Iran. A ceasefire was made in September 2011, but clashes still happen. Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, there have been accusations of discrimination by Western groups and claims of foreign involvement by Iran.

Kurds have been involved in Iranian politics for a long time. During the rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, some members of parliament and high army officers were Kurds. There was even a Kurdish Cabinet Minister. During the Pahlavi era, Kurds reportedly received many benefits. For example, they could keep their land after the land reforms of 1962. In the early 2000s, about thirty Kurdish members in the 290-member parliament showed that Kurds have a voice in Iranian politics. Important Kurdish politicians in recent years include former Vice President Mohammad Reza Rahimi and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the Mayor of Tehran.

The Kurdish language is used more now than at any time since the Revolution. It is used in newspapers and among schoolchildren. Many Kurds in Iran are not interested in Kurdish nationalism, especially Shia Kurds. They prefer direct rule from Tehran. Iranian national identity is only questioned in the Sunni Kurdish regions near the borders.

Syria

Kurds and other non-Arabs make up ten percent of Syria's population, about 1.9 million people. They are the largest ethnic minority in the country. Most are in the northeast and north, but there are also many Kurds in Aleppo and Damascus. Kurds often speak Kurdish in public. Kurdish human rights activists are often treated badly. No political parties are allowed for any group, Kurdish or otherwise.

To suppress Kurdish identity in Syria, the government has banned the Kurdish language. They refuse to register children with Kurdish names. They replace Kurdish place names with Arabic ones. They ban businesses that do not have Arabic names. They also ban Kurdish private schools and books written in Kurdish. About 300,000 Kurds have been denied Syrian nationality. This means they have no social rights and are stuck in Syria. However, in February 2006, there were reports that Syria planned to give these Kurds citizenship.

On March 12, 2004, clashes broke out between Kurds and Syrians at a stadium in Qamishli, a city where many Kurds live. The clashes continued for several days. At least thirty people were killed and over 160 were injured. The unrest spread to other Kurdish towns along the northern border with Turkey, and then to Damascus and Aleppo.

Armenia

Between the 1920s and 1990s, Armenia was part of the Soviet Union. Kurds, like other ethnic groups, were a protected minority. Armenian Kurds had their own state-supported newspaper, radio shows, and cultural events. During the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, many non-Yazidis and Kurds had to leave their homes. After the Soviet Union ended, Kurds in Armenia lost their cultural privileges. Most fled to Russia or Western Europe. The current parliament in Armenia reserves one seat for a Kurdish representative.

Republic of Azerbaijan

In 1920, two Kurdish areas, Jewanshir and eastern Zangazur, were combined to form the Kurdistan Okrug (or "Red Kurdistan"). This Kurdish administration was short-lived and ended by 1929. Kurds later faced harsh measures, including forced movements. Because of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, many Kurdish areas have been destroyed. More than 150,000 Kurds have been forced out by Armenian forces since 1988.

Kurds In Jordan, Syria, Egypt and Lebanon

The Kurdish leader Saladin, along with his uncles Ameer Adil and Ameer Sherko, led Kurdish fighters from cities like Tigrit, Mosul, and Erbil. They moved towards 'Sham' (today's Syria and Lebanon) to protect Islamic lands from Crusader attacks. The Kurdish King and his uncles ruled northern Iraq, Jordan, Syria, and Egypt for a short time. Saladin ruled in Syria, Ameer Sherko in Egypt, and Ameer Adil in Jordan. Other family members ruled most cities in today's Iraq.

The Kurds built many impressive castles in the lands they ruled. This was especially true in what was called 'Kurdistan of Syria' and in Damascus, the capital of Syria. A tall building called 'Qalha' still stands in Damascus. The Ayyubid dynasty, all of Kurdish descent, continued to rule there for many years.

Kurdish Genetics

Even though Kurds were ruled by many different groups over time, like Armenians, Romans, Arabs, and Ottomans, they may have remained relatively unchanged. This is because their mountainous homeland was protected and hard to reach.

Studies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the Near East show that Kurds, Azerbaijanis, Ossetians, and Armenians have a lot of mtDNA U5 lineages. These are common in Europe but rare elsewhere in the Near East.

Another study looked at both mitochondrial and Y chromosome DNA. It found that Kurdish groups are most genetically similar to other West Asian groups. They are most different from Central Asian groups. However, Kurdish groups are more closely related to European groups based on mtDNA. But they are closer to Caucasian groups based on the Y chromosome. This shows some differences in their maternal and paternal histories.

Studies also show a strong genetic link between Kurds and Azerbaijanis in Iran. They seem to share a common genetic background. Mitochondrial DNA in Georgians and Kurds is also very similar, even though they have different languages and histories. Both groups have mtDNA lineages that belong to the Western Eurasian gene pool.

In 2001, a study compared Jewish and non-Jewish groups from the Middle East. It found that Kurdish Jews and Sephardi Jews were very similar. Both differed slightly from Ashkenazi Jews. The study also found a strong genetic relationship between Jews and Iraqi Kurds. The conclusion is that these similarities come from ancient genetic patterns, not from recent mixing between the groups.

The Cohen modal haplotype, a specific genetic marker often found in Jewish people, was found in 10.1% of Kurdish Jews and 1.1% of Kurds. The most common Kurdish haplotype was shared by 9.5% of Kurds and 2.0% of Kurdish Jews. These findings suggest a shared ancient genetic background.

See also

- History of Iraqi Kurdistan

- List of Kurdish dynasties and countries

- Timeline of Kurdish uprisings

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |