Horatio Bottomley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Horatio Bottomley

|

|

|---|---|

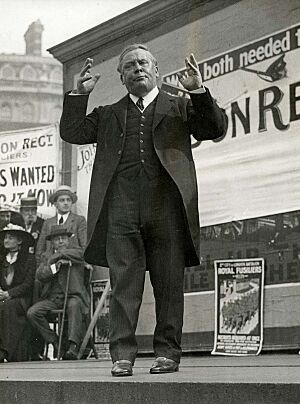

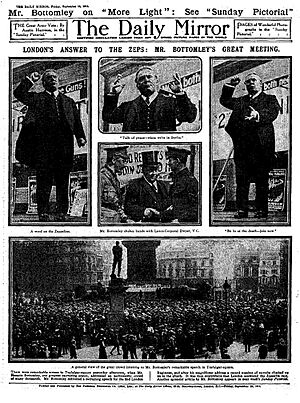

Bottomley speaking at a WWI recruiting rally in Trafalgar Square, London, September 1915

|

|

| Member of Parliament for Hackney South |

|

| In office 28 December 1918 – 1 August 1922 |

|

| Preceded by | Hector Morison |

| Succeeded by | Clifford Erskine-Bolst |

| In office 8 February 1906 – 16 May 1912 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Herbert Robertson |

| Succeeded by | Hector Morison |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 23 March 1860 London, England |

| Died | 26 May 1933 (aged 73) London, England |

| Political party | Liberal (1906–1912) Independent (1918–1922) |

Horatio William Bottomley (born 23 March 1860 – died 26 May 1933) was an English financier, journalist, editor, and Member of Parliament. He was famous for editing the popular magazine John Bull. He was also known for his powerful speeches during the First World War. His career ended in 1922 when he was found guilty of misusing money and sent to prison for seven years.

Bottomley spent five years in an orphanage as a child. At 14, he started working as an errand boy. He later learned about English law as a solicitor's clerk. This knowledge helped him a lot in court later on. At 24, he started his own publishing company. This company launched many magazines and papers, including the Financial Times in 1888. He faced his first accusations of financial wrongdoing in 1893. Even with evidence against him, Bottomley defended himself and was found not guilty. After this, he made a lot of money by promoting shares in gold-mining companies.

In 1906, Bottomley became a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for Hackney South. In the same year, he started John Bull magazine. This magazine became a place for Bottomley's strong popular opinions. But he continued to have money problems. In 1912, he had to leave parliament after running out of money. The start of World War I in 1914 changed his luck. As a journalist and speaker, Bottomley became a key supporter of the war effort. He gave over 300 public speeches. Many people thought he would join the War Cabinet, but he never received an offer.

In 1918, after his money problems were sorted, Bottomley returned to parliament as an Independent member. The next year, he started a misleading "Victory Bonds" scheme. When this scheme was revealed, he was found guilty, sent to prison, and removed from parliament. He was released in 1927. He tried to restart his business career but failed. He made a living by giving talks and appearing in music halls. He lived in poverty during his final years before he died in 1933.

Contents

- Horatio Bottomley's Early Life

- Death

- What People Thought of Horatio Bottomley

- Cultural Depictions

Horatio Bottomley's Early Life

Family and Childhood Years

Horatio Bottomley was born on 23 March 1860. He was born at 16 Saint Peter's Street in Bethnal Green, London. He was the second child and only son of William King Bottomley and Elizabeth (née Holyoake). His father, William, was a tailor's cutter. His mother, Elizabeth, came from a family of well-known activists. Her brother, George Jacob Holyoake, helped start the Secularist movement. He was also a leader in the Co-operative societies.

One of Holyoake's friends was Charles Bradlaugh. Bradlaugh started the National Republican League. He also became a well-known Member of Parliament. Bradlaugh and Elizabeth Holyoake were close friends for a long time. This led to rumors that Bradlaugh was Horatio's father, not William Bottomley. Horatio often encouraged this idea later in his life. The main reason for these rumors was that Bradlaugh and Bottomley looked very much alike.

William Bottomley died in 1864. Elizabeth died a year later. Horatio and his older sister, Florence, first lived with their uncle, William Holyoake. He was an artist in Marylebone, London. After a year, they went to live with foster-parents. Their uncle George Jacob paid for this. This arrangement lasted until 1869. Florence was then officially adopted by her foster family. At this point, George Jacob could no longer support Horatio financially. He arranged for Horatio to go to Josiah Mason's orphanage in Erdington, Birmingham. Horatio lived there for five years. Some writers say his time there was cruel. But Horatio received a good basic education. He also won prizes in sports. Later in life, he did not seem to resent the orphanage. He often visited it. He told the children that "any success I have achieved in life started at this place."

In 1874, Horatio was 14 years old. He was supposed to leave the orphanage. But he ran away without waiting for the official process. His aunt, Caroline Praill, who was his mother's sister, lived in nearby Edgbaston. She gave him a home. He worked as an errand boy for a building company in Birmingham. This lasted only a few months. Horatio wanted to see his sister again. They had been separated for six years. So, he went to London. There, he started learning to be a wood engraver.

Starting His Career

First Steps in London

Bottomley soon left his apprenticeship. After several ordinary jobs, he found work in the offices of a City law firm. Here, he learned a lot about English legal procedures. He quickly took on more work than a normal office junior. His uncle encouraged him to learn shorthand at Pitman's College. This skill helped him get a better job at a larger law firm. He also became more involved with the Holyoake group. He helped them with their publishing work without pay. He met Bradlaugh, who encouraged him to read widely. Bradlaugh also introduced him to the ideas of Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, and John Stuart Mill. Bottomley was greatly influenced by Bradlaugh. He saw him as his guide in politics and life.

As Bottomley grew from a teenager to an adult, he showed traits that would define his later life. He loved pleasures and wanted fame. He was also very generous. He had a charm that, according to one writer, could "tempt the banknotes out of men's pockets."

In 1880, Bottomley married Eliza Norton. She was the daughter of a debt collector. Writers have often seen this early marriage as a mistake for him. She was not able to help him advance in society. They had a daughter named Florence. Florence later married American millionaire Jefferson Davis Cohn. She then married South African planter Gilbert Moreland. In the year he married, Bottomley left his job. He became a full-time shorthand writer for Walpole's. This company recorded and transcribed court proceedings. His skills impressed his employers. In 1883, they offered him a partnership. The firm became Walpole and Bottomley.

Becoming a Publishing Entrepreneur

Bottomley's connection with Bradlaugh made him interested in publishing and politics. In 1884, he started his first business venture. It was a magazine called the Hackney Hansard. This magazine reported on the local "parliament" in Hackney. This was a debating society that copied the real parliament in Westminster. Advertisements from local businesses kept the paper slightly profitable. Bottomley then created a similar paper, the Battersea Hansard. This covered the local parliament in that area. Later, he combined the two into The Debater.

In 1885, he formed the Catherine Street Publishing Association. Using borrowed money, he bought or started several magazines and papers. These included the Municipal Review, a respected local government publication. He also started Youth, a boys' paper. Alfred Harmsworth, who would become the famous press owner Lord Northcliffe, worked as a sub-editor there. Bottomley also started the Financial Times. This paper was created to compete with the Financial News. That was London's first special business paper, started in 1884. In 1886, Bottomley's company got its own printing works. This happened through a merger with MacRae and Co. After taking over another advertising and printing firm, it became MacRae, Curtice and Company.

At 26, Bottomley became the company's chairman. His rise in business was getting noticed. In 1887, the Liberal Party in Hornsey asked him to be their candidate in a special election for parliament. He accepted. He lost the election to Henry Charles Stephens, a ink maker. But he ran a strong campaign. He even received a congratulatory letter from William Ewart Gladstone. His business affairs were not going as smoothly. He argued with his partner, Douglas MacRae. They decided to separate. Bottomley said he made a "Quixotic impulse" by letting MacRae divide the assets. He explained: "He was a printer, and I was a journalist—but he took the papers and left me the printing works."

The Hansard Publishing Union

Bottomley was not discouraged by losing his papers. He started an ambitious expansion plan. He got a good contract to print the Hansard reports of debates in the Westminster parliament. Based on this, in early 1889, he founded the Hansard Publishing Union Limited. This company was launched on the London Stock Exchange with £500,000. Bottomley made the company look more impressive. He convinced several important City figures to join the company's board of directors. These included Sir Henry Isaacs, the future Lord Mayor of London. Also, Coleridge Kennard, who helped start the London Evening News, joined. And Sir Roper Lethbridge, a Conservative MP, was on the board.

This board approved Bottomley buying several printing businesses. He used other people to hide his large personal profits from these deals. He also convinced the board to give him £75,000 as a down payment for some publishing firms in Austria. However, these firms were never bought. These payments and other costs used up the Union's money. With few ways to earn money, it quickly ran out. Even so, without any financial reports, in July 1890, Bottomley announced a profit of £40,877 for the year. He declared an eight percent dividend.

The money for the dividend came from a loan of £50,000. By the end of 1890, many people in the City were suspicious of the Hansard Union. They called it "Bottomley's swindle." Despite Bottomley's hopeful attitude, in December 1890, the company failed to pay interest on its loan. In May 1891, with growing rumors of money problems, the lenders asked for the company to be closed down. In the same month, Bottomley, who had taken at least £100,000 from the company, declared himself out of money. When questioned by the Official Receiver, he could not say where the money went. He claimed he knew nothing about the company's accounting. After more investigations, the Board of Trade started legal action for financial wrongdoing against Bottomley, Isaacs, and two others.

The trial began in the High Court of Justice on 30 January 1893. Sir Henry Hawkins was the judge. Bottomley defended himself. To most people, the case against him seemed very strong. It was shown that, through people working for him, Bottomley had repeatedly bought companies for much less than the prices approved by the Hansard Union directors. He had kept the difference. Bottomley did not deny this. He said that using nominees was a normal business practice. He also claimed his actual profits were much smaller than reported. His expenses, he said, had been huge.

He was helped by the prosecution's weak presentation of evidence. They also failed to call important witnesses. He was further helped by how understanding Hawkins was towards him. His own convincing speaking skills also helped. The main point of his argument was that he was a victim. He claimed the Official Receiver and the Debenture Corporation wanted to gain prestige by bringing him down and ruining his company. On 26 April, after Hawkins had largely supported him in his summary, Bottomley was found not guilty. The other defendants were also acquitted.

Business and Politics

Gold Mining and a New Lifestyle

The Hansard Union case, instead of harming Bottomley's reputation, made people think he was a financial genius. He avoided the shame of running out of money by arranging to pay back his creditors. He quickly started a new career promoting gold mining shares in Western Australia. Gold had been found in Kalgoorlie in the early 1890s. This created an easy investment boom. As one writer noted, "A hole in the ground... could be boosted into a very promising gold-mine." Investors only found out they had lost money after the mine was sold as a public company and they had paid for their shares.

By 1897, Bottomley had gained a lot of personal wealth. He did this by cleverly using demand and by often reorganizing companies that were failing. One historian called it "a truly amazing success story." It was the result of being very bold, having amazing energy, and being very lucky. Bottomley was praised when he announced he would pay £250,000 to the creditors of the Hansard Union. Most of this payment was offered in shares from his mining promotions.

As he became richer, Bottomley started living a very showy lifestyle. In London, he lived in a fancy apartment in Pall Mall. He owned several racehorses that won important races. These included the Stewards' Cup at Goodwood and the Cesarewitch at Newmarket. But he often lost large amounts of money on bets. Early in his rise to wealth, he bought a small property in Upper Dicker, near Eastbourne in East Sussex. He called it "The Dicker." Over the years, he made it bigger and turned it into a large country mansion. There, he entertained guests in a very grand way.

Bottomley still wanted to be in parliament. In 1890, before the Hansard Union crash, he was chosen as the Liberal candidate for North Islington. When he had to step down because of his money problems, he had already gained strong support in the area. By 1900, he was doing well again. The Hackney South Liberals asked him to be their candidate in the general election that year. He lost by only 280 votes. It was a very tough campaign. A newspaper article called Bottomley a "bare-faced swindler... whose place is at the Old Bailey, not at Westminster." He later won £1,000 in damages for this false statement against the writer, Henry Hess.

Around 1900, the boom in risky shares slowed down. Some of Bottomley's fellow promoters, like Whitaker Wright, were facing accusations of financial wrongdoing. Bottomley stopped his operations. He went back to his earlier role as a newspaper owner. In 1902, he bought a struggling London evening paper, The Sun. He wrote a regular column for it called "The World, the Flesh and the Devil." Another special feature was Bottomley hiring famous guest editors for special editions. These included comedian Dan Leno, cricketer Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji, and labor leader Ben Tillett.

The paper was not a financial success. Bottomley sold it in 1904. He had not completely given up on making money from risky schemes. In 1905, he started working with financier Ernest Hooley. One of their joint projects was promoting the old, dry Basingstoke Canal as a major waterway. They called it the "London and South-Western Canal." Bottomley later paid a large sum of money outside of court. This was to settle a lawsuit from investors who had bought worthless shares in the canal.

Parliament, John Bull, and Financial Troubles

In the general election of January 1906, Bottomley was again the Liberal candidate for Hackney South. After a strong campaign, he defeated his Conservative opponent by over 3,000 votes. He told the House of Commons in his first speech on 20 February 1906 that this was the largest Liberal majority in London. According to one writer, this speech was met with "chilling silence." The House was well aware of Bottomley's mixed reputation.

Over the next months and years, he overcame much of the initial dislike. He did this partly with his humble humor. For example, he once called himself "more or less honourable." But also, his popular approach to laws was appealing. He suggested sensible changes to the betting industry and drinking hours. He also proposed starting state Old Age Pensions. He said more money could be raised by taxing share transfers, foreign investments, and by using unused bank balances. He brought attention to the long hours worked by domestic servants. He introduced a bill to limit their workday to eight hours. He privately told journalist Frank Harris that he wanted to become Chancellor of the Exchequer.

While doing his parliamentary duties, Bottomley was also launching his biggest publishing project. This was the weekly news magazine John Bull. Half of the starting money came from Hooley. From its first issue on 12 May 1906, John Bull used a tabloid style. Despite some taste issues, it became very popular. Among its regular features, Bottomley brought back his "The World, the Flesh and the Devil" column from The Sun. He also used that paper's slogan: "If you read it in John Bull, it is so." Bottomley convinced Julius Elias, a director at Odhams Limited, to handle the printing. But messy financial management meant Odhams was rarely paid. This problem was solved when Elias took over all management of the magazine. This included all money coming in and going out. This left Bottomley free to focus on editing and writing. Circulation grew quickly. By 1910, it reached half a million copies.

In June 1906, Bottomley announced the John Bull Investment Trust. For a minimum payment of £10, investors could share "special and exclusive information." This information, he said, was only available from wide City experience. Bottomley's earlier business activities were being looked at closely. This was especially true for the many reorganizations of his now-bankrupt Joint Stock Trust Company. After a long investigation, which Bottomley tried hard to stop, he was called to appear at the Guildhall Justice Room in December 1908. He appeared before a court of aldermen. As with the Hansard case, the evidence against Bottomley seemed very strong. Share issues in the Joint Stock Trust had been re-issued many times, perhaps as many as six. Again, Bottomley managed to make the details unclear. With his powerful speaking skills in court, he convinced the court that the summons should be dismissed.

One of the lawyers in the Guildhall case said it would be a long time before anyone risked another case against Bottomley. "But he might... grow careless, and then he will fail." Despite the bad publicity, Bottomley was re-elected by the people of Hackney South in both 1910 general elections. His tactics included hiring men with iron-tipped boots. These men marched outside his opponent's meetings, making the speeches impossible to hear. In June 1910, he founded the John Bull League. Its goal was to bring "commonsense business methods" into government. Readers of the magazine could join the League for a shilling (5p) a year. Although still a Liberal, Bottomley had become a strong critic of his party. He often sided with the Conservative opposition in attacking Asquith's government.

Bottomley's parliamentary goals suddenly stopped in 1912. He was successfully sued for £49,000 by someone who had lost money in his Joint Stock Trust. He could not pay. With huge debts, he was declared bankrupt with total debts of £233,000. People who are bankrupt cannot be in the House of Commons. So, he had to resign his seat. After he left, F. E. Smith, who would become Lord Chancellor, wrote that his absence "impoverished the public stock of gaiety, of cleverness, of common sense." Before his bankruptcy, Bottomley made sure his main assets were legally owned by relatives or others. This way, he could continue his expensive lifestyle. John Bull remained a good source of money. Bottomley boasted that even though he was officially bankrupt, "I never had a better time in my life—plenty of money and everything else I want as well."

Sweepstakes and Lotteries

After leaving the House of Commons, Bottomley criticized Parliament in John Bull. He called it a "musty, rusty, corrupt system" that needed to be replaced. Through his new Business League, he spoke to large crowds. He called for government to be run by business people, not politicians. As always, Bottomley's lifestyle needed new sources of income. In 1912, John Bull began to organize competitions with cash prizes. Bottomley successfully sued the secretary of the Anti-Gambling League. The secretary had suggested that many prize winners were connected to John Bull. Bottomley only received a very small amount in damages. These competitions helped raise the magazine's circulation to 1.5 million.

In 1913, Bottomley met Reuben Bigland, a businessman from Birmingham. Together, they started running large-scale sweepstakes and lotteries. They operated them from Switzerland to get around English law. Again, doubts arose about whether the declared winners were real. The winner of the £25,000 sweepstake for the 1914 Derby was found to be the sister-in-law of one of Bottomley's close friends. Bottomley insisted this was a coincidence. Years later, it was revealed that almost all of the prize money had gone into a bank account controlled by Bottomley.

First World War: Speaker and Supporter

Bottomley first misunderstood the international crisis in the summer of 1914. After the murder of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June, John Bull called Serbia "a hotbed of cold-blooded conspiracy." It said Serbia should be removed from the map of Europe. When Britain declared war on the Central Powers on 4 August, Bottomley quickly changed his view. Within two weeks, he was demanding the elimination of Germany. John Bull constantly campaigned against "Germhuns" and British citizens with German-sounding names. The danger of "the enemy within" was a common theme for Bottomley.

On 14 September 1914, he spoke to a large crowd at the London Opera House. This was the first of many big meetings. He used his famous phrase, "the Prince of Peace, (pointing to the Star of Bethlehem) that leads us on to God." According to one writer, these words touched many hearts. At the "Great War Rally" at the Royal Albert Hall on 14 January 1915, Bottomley was in tune with the national mood. He declared: "We are fighting all that is worst in the world, the product of a debased civilisation."

During the war, Bottomley became a self-appointed spokesman for the "man in the street." He gave over 300 public speeches across the country. For recruitment rallies, he spoke for free. For other events, he took a percentage of the money collected. His influence was huge. The writer D. H. Lawrence, who disliked Bottomley, thought he represented the national spirit. Lawrence even thought Bottomley might become prime minister.

In March 1915, Bottomley began a regular weekly column for the Sunday Pictorial. On 4 May, after the sinking of the Lusitania, he used his column to call for the extermination of Germans. He claimed Britain's war effort was being held back by weak politicians. He especially criticized Labour Party leaders, Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald, who opposed the war. Bottomley also criticized the United States' neutrality policy. He argued the USA was using the war to increase its economic power. Bottomley launched many attacks on President Woodrow Wilson. These lasted until the US entered the war in 1917.

The government was cautious about Bottomley. But it was willing to use his influence and popularity. In April 1915, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, asked him to speak to shipworkers on the River Clyde. They were threatening to strike. After Bottomley's speech, the strike was avoided. In 1917, he visited the front in France. After dining with Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, he was very popular with the troops. His later visit to the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow was also a success. He hoped these morale-boosting activities would lead to a formal government job. But although there were rumors of a Cabinet position, no appointment was ever made. Later in the war, Bottomley often criticized the National War Aims Committee (NWAC). This was a cross-party group formed in 1917 to strengthen Britain's commitment to victory. Bottomley called the committee "a dodge for doctoring public opinion." In January 1918, he told Lloyd George, who was prime minister, that NWAC had failed. He said it should be replaced by a Director of Propaganda, but nothing changed.

After the War

Back in Parliament

Even though Bottomley had shown contempt for parliament in 1912, he secretly wanted to return. When the war ended in November 1918, a general election was announced. He knew he needed to clear his bankruptcy to be a candidate. A payment of £34,000 in cash and bonds, and some quick reorganization of old debts, was enough. An agreeable Official Receiver granted the clearance just in time. This allowed Bottomley to submit his nomination papers in Hackney South. In the general election on 14 December 1918, he ran as an Independent. His slogan was "Bottomley, Brains and Business." He won a huge victory, with almost 80 percent of the votes. He told a local newspaper, "I am now prepared to proceed to Westminster to run the show." He said he would be the "unofficial prime minister." He would "watch the government's every move" to make sure it acted for "our soldiers, sailors and citizens."

The 1918 parliament was mostly controlled by Lloyd George's Liberal–Conservative coalition. It faced a divided opposition. In May 1919, Bottomley announced his "People's League." He hoped it would become a full political party. Its program would oppose both organized labor and organized capital. No large movement came from this. But Bottomley joined other Independent MPs to form the Independent Parliamentary Group. This group had clear policies. These included enforcing war payments, Britain being superior to the League of Nations, keeping out unwanted foreigners, and "introducing business principles into government." The group grew stronger with wins by other Independents in special elections. This included Charles Frederick Palmer, John Bull's deputy editor, until his early death in October 1920.

For about a year, Bottomley was a hardworking Member of Parliament. He spoke on many different topics. Sometimes he teased the government. For example, during the Irish Troubles, he asked if, "in view of the breakdown of British rule in Ireland, the government will approach America with a view to her accepting the mandate for the government of that country." Other times, he helped the government. In January 1919, he was called upon as "Soldier's Friend." He helped calm down troops in Folkestone and Calais. They were upset about delays in being sent home.

His Downfall

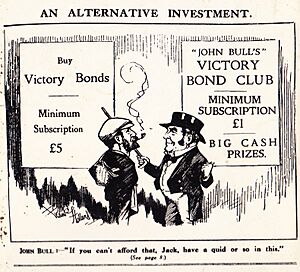

In July 1919, Bottomley announced his "Victory Bonds Club." This club was based on the government's newest Victory Bonds. Normally, these bonds cost £5. In Bottomley's club, people paid a minimum of £1. They then took part in a yearly draw for prizes, up to £20,000, he said. These prizes were funded from the interest earned. But not all the money paid by subscribers was used to buy bonds, despite Bottomley's public statements. He wanted to become a powerful newspaper owner, like Lord Rothermere and Lord Beaverbrook.

In October 1919, he used money from the War Bonds to buy two little-known newspapers. These were the National News and the Sunday Evening Telegram. The papers did not do well financially. In 1921, Bottomley closed the Telegram. He changed the name of the National News to Sunday Illustrated. To help it, he moved his Sunday Pictorial column to the Illustrated. He also ran an expensive advertising campaign, but it did little good. The paper struggled. Bottomley lost the large income and readership he had from the Pictorial. His situation got worse in 1920. Odhams ended their pre-war agreement and took full control of John Bull. Bottomley was made editor for life. But a year later, Odhams ended this deal with a final payment of £25,000. This ended Bottomley's connection with the paper.

Meanwhile, the Victory Bonds Club was falling apart. This was due to poor management and bad accounting. Public concern grew. Soon, hundreds of people were asking for their money back. Because records were messy, some people were paid back several times. Bottomley's situation worsened when he argued with Bigland. This happened after Bottomley refused to fund Bigland's idea for turning water into petrol. The two had argued during the war, when Bigland had attacked Bottomley in print. They had later made up. But after their second dispute, Bigland sought revenge. In September 1921, he published a leaflet. It called the War Bond Club Bottomley's "latest and greatest swindle." Against his lawyers' advice, Bottomley sued for false statements. He also brought other charges against Bigland for blackmail. The first hearing, at Bow Street Magistrates' Court in October 1921, revealed Bottomley's methods. This greatly damaged his trustworthiness. Nevertheless, Bigland was sent to trial at the Old Bailey for the false statements charge. He was also sent to Shropshire Assizes for attempted extortion.

The trial for false statements began on 23 January 1922. To prevent more damaging information from coming out in court, Bottomley's lawyers offered no evidence. Bigland was released. The extortion case went ahead in Shrewsbury on 18 February 1922. At the end of it, the jury took only three minutes to find Bigland not guilty. Bottomley, who was now under police investigation himself, was ordered to pay the trial costs. A few days later, he was ordered to appear at Bow Street. He faced charges of misusing Victory Bond Club funds. After a short hearing, he was sent to trial at the Old Bailey.

Final Years

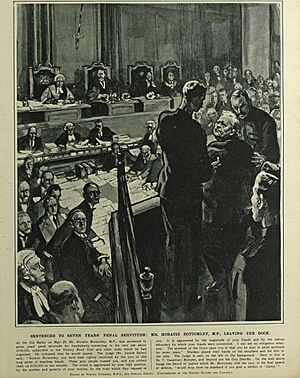

Bottomley's trial began on 19 May 1922, before Mr Justice Salter. As the case started, Bottomley got the agreement of the prosecuting lawyer, Travers Humphreys. He was allowed a 15-minute break each day to drink a pint of champagne. He claimed this was for health reasons. He faced 24 charges of financial wrongdoing. These involved amounts totaling £170,000. The prosecution showed evidence that he had regularly used Victory Bonds Club money. He used it to fund his businesses, pay private debts, and support his expensive lifestyle.

Bottomley defended himself. He claimed his proper expenses related to the club, and money paid back to members, were more than the total money received by at least £50,000. He said: "I swear I have never made a penny out of it. I swear before God that I have never fraudulently converted a penny of the Club's money." But the evidence suggested otherwise. Salter's summary, described as "masterly; lucid and concise, yet complete," was strongly against Bottomley. The jury took only 28 minutes to find him guilty on almost all charges. He was sentenced to seven years of hard labor. Humphreys later commented: "It was not I that floored him, but Drink."

After his appeal was rejected in July, Bottomley was removed from the House of Commons. The Leader of the House, Sir Austen Chamberlain, read a letter from Bottomley. In it, Bottomley insisted that, despite his unusual methods, he had not knowingly committed financial wrongdoing. He accepted that his situation was entirely his own fault. Chamberlain then moved for Bottomley's expulsion, which passed without disagreement. One member expressed regret, "remembering the remarkable position which he [had] occupied in the country." Bottomley spent the first year of his sentence in Wormwood Scrubs. There, he sewed mailbags. He spent the rest of his time in Maidstone Prison. Although conditions were poor, he was given lighter work. He was released on 29 July 1927, after serving just over five years. He returned to The Dicker, which was still his family home. At the time of his bankruptcy, it was owned by his son-in-law, Jefferson Cohn.

Although he was 67 years old and not in good health, Bottomley tried to restart his business career. He raised enough money to start a new magazine, John Blunt. This was meant to rival John Bull. But the new venture lasted little more than a year before closing. It had lost money from the start. In September 1929, he began a lecture tour overseas. This failed completely. An attempt at a British tour also failed. He was met with indifference or hostility. By 1930, he was again out of money. His wife Eliza died that year. After that, Bottomley's former son-in-law, Jefferson Cohn, evicted him from The Dicker. For the rest of his life, he lived with his long-time partner, the actress Peggy Primrose. Bottomley had tried to make her a star when he was rich, but failed.

Bottomley's last public effort was a show at the Windmill Theatre in September 1932. He performed a monologue of memories. According to one writer, it confused his audience more than it amused them. After a health breakdown, he lived with Primrose in quiet poverty until his final illness.

Death

Bottomley died at the Middlesex Hospital on 26 May 1933, at the age of 73. His body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium a few days later. A large crowd heard the Reverend Basil Bourchier express hope that "no one here today will forget what Mr Bottomley did to revive the spirits of our men at the Front." Four years later, as Bottomley wished, Primrose scattered his ashes on the Sussex Downs.

What People Thought of Horatio Bottomley

Bottomley's obituaries (death notices) often talked about his wasted talent. They said he was a man with brilliant natural abilities, but his greed and vanity ruined him. "He had personal magnetism, eloquence, and the power to convince," wrote his Daily Mail obituarist. "He might have been a leader at the Bar, a captain of industry, a great journalist. He might have been almost anything." The Straits Times of Singapore thought Bottomley could have been as great a national leader as Lloyd George. "Though he deserved his fate, the news of his passing will awaken the many regrets for the good which he did when he was Bottomley the reformer and crusader and the champion of the bottom dog." A later historian, Maurice Cowling, praised Bottomley's ability and hard work. He also noted his strong campaigns for freedom. In his description for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Morris gave a different opinion: "He claimed to serve the interests of others, but sought only his own gratification."

Among Bottomley's main biographers, Hyman suggested that his financial carelessness and disregard for consequences might have come from his poor background. He then suddenly became rich in the 1890s. "Success went to his head and he started spending money like a drunken sailor and could never break the habit." Hyman said it was a wonder he stayed out of prison for so long. G. R. Searle wondered if Bottomley was protected from legal action. This might be because he knew about bigger scandals in the government. This was especially true after Lloyd George's coalition took power in 1916. Symons recognized Bottomley's "wonderfully rich public personality." But he suggested there was no real person behind the public image. Throughout his adult life, Bottomley was "more a series of public attitudes than a person." Matthew Engel in The Guardian noted his ability to charm the public even while taking their money. One person, who lost £40,000, reportedly insisted: "I am not sorry I lent him the money, and I would do it again." Engel said if London had had a mayor back then, Bottomley would have won easily.

Cultural Depictions

- Actor Timothy West played Bottomley in the 1972–1973 miniseries The Edwardians.

- Actor Patrick Mower played Bottomley in a radio play by Allen Saddler about him called Man of the People. It was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 1986 and in June 2022 on BBC Radio 4 Extra.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |