Hurricane Audrey facts for kids

Radar image of Audrey prior to landfall

|

|

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | June 25, 1957 |

| Dissipated | June 29, 1957 |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 125 mph (205 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 946 mbar (hPa); 27.94 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 416 |

| Damage | $150 million (1957 USD) |

| Areas affected | South Central United States (particularly Texas and Louisiana), Southeastern United States, Midwestern United States, New England, Quebec, Ontario |

|

Part of the 1957 Atlantic hurricane season |

|

Hurricane Audrey was one of the deadliest hurricanes in U.S. history. It killed at least 416 people when it hit the southwestern Louisiana coast in 1957. Audrey was also one of the strongest June hurricanes ever recorded in the Atlantic Ocean. It was as strong as Hurricane Alex in 2010.

Before reaching land, Audrey caused big problems for offshore drilling in the Gulf of Mexico. The damage to oil facilities alone was about $16 million. Audrey caused most of its destruction near the border between Texas and Louisiana. The hurricane's strong winds damaged many buildings and power lines. This led to widespread power outages.

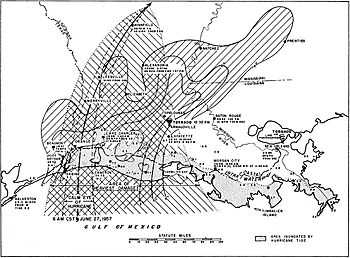

However, most of the damage near the coast came from the hurricane's powerful storm surge. This was a huge wall of water pushed onto land by the storm. The storm surge was as high as 12 feet (3.7 m). It flooded coastal areas up to 25 miles (40 km) inland. In Louisiana and Texas, where Audrey first hit, the damage cost $128 million.

After moving inland, Audrey changed into a different type of storm. It still caused more damage across the central United States. In total, Audrey killed at least 416 people in the U.S. The exact number might never be known. The total damage in the country was $147 million. At that time, it was the fifth most expensive hurricane in the U.S. since 1900. Because of its severe impact, the name Audrey was later retired. This means it will never be used again for an Atlantic hurricane.

Contents

How Hurricane Audrey Formed and Grew

Hurricane Audrey's journey began with a low-pressure area. This area was first noticed high up in the western Caribbean Sea on June 11. Weather experts were studying these kinds of disturbances. They hoped to learn more about how tropical cyclones form. At the same time, a tropical wave was moving west across the Caribbean Sea. It entered the Bay of Campeche by June 22.

From Tropical Depression to Hurricane

On June 24, storms from this wave organized into a tropical depression. This was based on reports from ships in the bay. The depression was in a perfect spot to get stronger in the western Gulf of Mexico. The ocean water was very warm, about 85 °F (29 °C). This was warmer than usual for that time of year. Also, the air currents high up in the atmosphere helped the storm grow. Because of these good conditions, Audrey became a tropical storm just six hours later. It stayed almost still for a while.

On June 25, the first special aircraft, called reconnaissance aircraft, flew into Audrey. They found that Audrey had become a hurricane. This was a fast strengthening period for the storm. Audrey then started moving slowly north. Its strengthening slowed down on June 26. But the aircraft saw that the storm was producing more rain.

Audrey's Rapid Strengthening Before Landfall

The next day, Audrey started getting much stronger again. It sped up towards the United States Gulf Coast. By June 27, it was a Category 2 hurricane. Just six hours later, it became a Category 3 hurricane. The storm's pressure dropped a lot before it hit land. This meant it was getting more intense.

Audrey made landfall on June 27 at 8:30 a.m. CST. It hit just east of the Texas and Louisiana border. At its strongest, Audrey had winds of 125 mph (200 km/h). Its central pressure was 946 mbar. Some reports from an oil rig suggested even stronger winds, but these were not confirmed. Radar showed that the storm had two eyewalls. This meant it had two areas of very strong winds.

Weakening and Final Stages

After hitting land, Audrey slowly weakened. It turned towards the northeast. By June 28, it was just a tropical storm. An approaching cold front caused Audrey to change into an extratropical cyclone. This change finished on June 29 over West Virginia.

Later, the remains of Audrey joined with another extratropical cyclone. This happened over the Great Lakes. The combined storm unexpectedly got stronger. It even produced hurricane-force winds as it moved across the Northeastern United States. This was similar to how Hurricane Hazel behaved in 1954.

Getting Ready for Hurricane Audrey

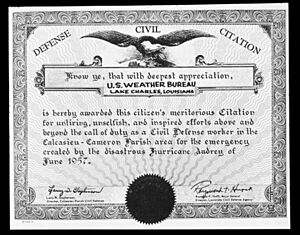

Even though Audrey's exact formation wasn't predicted, the Weather Bureau had given a general hurricane forecast. They said there was a high chance of tropical storms in June. The first official notice about Audrey came on June 25. At that time, Audrey was still a tropical depression.

Warnings and Evacuations

A hurricane watch was put in place for the Texas and Louisiana coasts the next day. Then, a full hurricane warning was issued for the entire Louisiana coast on June 26. The Weather Bureau pointed out that Audrey's path was similar to Hurricane Flossy from 1956. This helped convince people in Grand Isle, Louisiana, to leave.

About 75,000 people left low-lying areas along the U.S. Gulf Coast before Audrey hit. In Texas, 270 beach houses were evacuated. Hundreds of workers were flown off offshore oil rigs on June 26. Around 50,000 people left Port Arthur, Texas. Almost everyone left Sabine Pass.

In Louisiana, the state's civil defense groups helped with evacuations. They used National Guard equipment and people. About 3,400 people left Grand Isle, Louisiana. However, 600 people chose to stay. Most of Cameron, Louisiana, was evacuated. The American Red Cross opened many shelters. They housed thousands of people and gave out food. The United States Air Force and United States Navy moved their aircraft to safer bases.

Why So Many Deaths?

The high number of deaths from Audrey was partly because not everyone evacuated in time. Meteorologist Robert Simpson said this was due to poor communication. The Weather Bureau's warnings were correct. But they didn't sound urgent enough. The warnings told people in "low or exposed areas" to leave. But many people living just 7-8 feet (2-2.4 m) above sea level didn't think they were in a "low" area.

Also, new city officials in Lake Charles, Louisiana, changed the warnings. They removed details they thought were not important. This might have made people hesitate to leave until it was too late.

Hurricane Audrey's Impact

The Weather Bureau first thought over 500 people died from Audrey. They estimated the damage at $150–200 million. Other estimates said about 390 people died. This included 263 identified people and 127 unidentified. Another 192 people were reported missing. The National Weather Service says Audrey caused at least 416 deaths in the U.S. Another 15 people died in Canada.

Audrey was the deadliest hurricane to hit the United States since the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane. That storm killed about 2,500 people. Nearly all the deaths in Audrey were from drowning in the storm surge.

After the Storm: Recovery and Changes

After the storm, United States Coast Guard rescue teams quickly went to the Cameron area. They searched for survivors. The Coast Guard also sent a boat from New Orleans with medical supplies. More than 40,000 people lost their homes. Many stayed at McNeese State University in Lake Charles until they could find new places to live. Statues were put up in southwestern Louisiana to honor those who died. This included a memorial park in Lake Charles where 33 people were buried.

Changes to the Coastline and Wildlife

Audrey's storm surge on the Louisiana coast went back to normal levels in about 1.5 days. Even though the flooding was brief, the coast changed a lot. About half of the coast moved inland. A lot of mud was left behind. One large area of mud was over 11,000 feet (3,459 m) long.

In Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge, saltwater flooded the animal habitats. This caused a big drop in waterfowl and plants that can't handle saltwater. The damage set back plans for the refuge by two years. Many animals like nutria, muskrat, raccoon, rabbit, and deer died. Their populations dropped by 60%. All animal nests were washed away by the waves or strong winds.

Lessons Learned for Future Storms

The huge damage in Cameron, Louisiana, helped with future evacuations. Four years later, when Hurricane Carla threatened, almost everyone in Cameron Parish evacuated. This was a very high evacuation rate. People remembered what happened with Audrey. This is sometimes called the "Audrey effect."

The large storm surge from Audrey also helped scientists. It was the first big storm surge for the new National Hurricane Research Project (NHRP) to study. They learned that they needed more information from inland areas to understand storm surges better. This data would help local emergency teams and improve surge forecasts. After Hurricane Audrey, the Weather Bureau started putting more tide recorders along the coast.

Because of the damage and deaths, the name Audrey was retired. It will never be used again for an Atlantic tropical cyclone.

More About Hurricanes

- List of Texas hurricanes (1950–79)

- List of Category 3 Atlantic hurricanes

- Other tropical cyclones named Audrey

Storms That Hit Similar Areas

- Hurricane Carmen (1974) – A very strong Category 4 hurricane that hit the Yucatán Peninsula and southern Louisiana.

- Hurricane Rita (2005) – A powerful Category 5 hurricane that caused major damage in southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas.

- Hurricane Laura (2020) – A very damaging Category 4 hurricane that caused widespread destruction across western Louisiana and eastern Texas.

Other Strong Early-Season Hurricanes

- 1909 Velasco hurricane – A Category 3 hurricane that caused a lot of damage on the Texas coast.

- 1916 Gulf Coast hurricane – A destructive Category 3 hurricane that hit the central Gulf Coast of the United States.

- Hurricane Beryl (2024) – A record-breaking Category 5 hurricane that moved through the Caribbean Sea.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |