Indian indenture system facts for kids

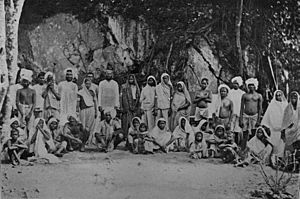

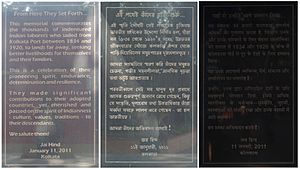

The Indian indenture system was a way that over 1.6 million workers from India were sent to work in European colonies. This system started because slavery was being abolished in the early 1800s. After slavery ended in the British Empire in 1833, in French colonies in 1848, and in Dutch colonies in 1863, the need for workers grew. The British Indian indenture system lasted until the 1920s.

This system led to many people of Indian descent living in places like the Caribbean, South Africa, East Africa, Réunion, Mauritius, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Fiji. This created large Indian communities in these regions.

Contents

- First Workers Arrive

- British India's Rules for Workers

- Temporary Ban on Indian Workers

- Restarting Worker Transportation

- Efforts to Stop Abuses

- Indian Workers in the Caribbean

- Encouraging Workers to Stay Longer

- Recruitment for Other European Colonies

- Indenture to Other British Empire Parts

- Improving the British Indian Labor System

- Transportation to Suriname

- Indian Workers in British and French Colonies (1842-1870)

- The Indenture Agreement (1912)

- End of the Indenture System

- Indian Indentured Workers by Colony (1842-1870)

- Cultural Impact

- Population Changes

- See Also

First Workers Arrive

On January 18, 1826, the French island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean set rules for bringing in Indian workers. Each worker had to tell a judge that they were going willingly. This agreement was called "girmit." It promised five years of work in the colonies. Workers would earn 8 rupees (about $4) per month and get food. This was for workers from Pondicherry and Karaikal.

The first try to bring Indian workers to Mauritius in 1829 failed. But by 1838, about 25,000 Indian workers had been sent there.

The Indian indenture system began because sugar plantation owners in the colonies needed cheap and reliable labor. They hoped this system would be like slavery but would show that "free" labor was better.

British India's Rules for Workers

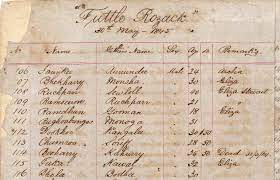

The East India Company made rules in 1837 for sending Indian workers from Calcutta. A worker and their agent had to meet with a British Indian government official. They would show a written contract.

The contract said workers would serve for five years. They could renew it for more five-year terms. Workers were supposed to be sent back to their home port after their service. Each ship carrying workers had to meet certain standards for space and food. It also had to have a medical officer. In 1837, these rules were also used for workers from Madras.

Temporary Ban on Indian Workers

When people learned about this new system, a campaign started in Britain and British India. It was similar to the anti-slavery movement. On August 1, 1838, a committee was formed to look into the export of Indian workers. They heard about many problems and abuses in the system.

On May 29, 1839, sending manual laborers overseas was banned. Anyone who helped with such emigration could face a 200 Rupee fine or three months in jail. After the ban, some Indian workers still went to Mauritius through Pondicherry, which was a French area in South India.

However, sending workers was allowed again in 1842 for Mauritius. In 1845, it was allowed for the West Indies. There were other times when Indian immigration was stopped in the 1800s. For example, from 1848 to 1851, it stopped for British Guiana due to economic problems.

Restarting Worker Transportation

European plantation owners in Mauritius and the Caribbean worked hard to end the ban. At the same time, the anti-slavery group tried to keep it. The British East India Company finally gave in to pressure from the planters.

On December 2, 1842, the British Government allowed workers to leave from Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras for Mauritius. Agents were appointed at each departure point. There were penalties for abusing the system. Workers were supposed to get a return trip home after five years if they asked for it.

After the ban was lifted, the first ship left Calcutta for Mauritius on January 23, 1843. The Protector of Immigrants in Mauritius reported that many ships were arriving. This caused a big backlog in processing the new workers. In 1843, 30,218 male and 4,307 female indentured workers came to Mauritius. The first ship from Madras arrived in Mauritius on April 21, 1843.

Efforts to Stop Abuses

The rules in place did not stop abuses in the system. Workers were still recruited with false promises. Because of this, in 1843, the Government of Bengal had to limit emigration from Calcutta. Workers could only leave after signing a certificate from the Agent, which the Protector also had to sign.

Migration to Mauritius continued. In 1844, 9,709 unskilled male laborers (called Dhangars) and 1,840 female wives and daughters were transported. Sending Indians home after their service was still a problem. Many died, and investigations showed that rules for return trips were not followed well.

There were not enough workers from Calcutta to meet the demands of European planters in Mauritius. So, in 1847, permission was given to restart emigration from Madras. The first ship left Madras for Mauritius in 1850.

Company officials were also stationed in colonies that hosted Indian immigrants. For example, when Danish plantation owners started hiring Indians, the British representative in the Danish West Indies was called the Protector of Immigrants. This official looked after the workers' well-being. They made sure the terms of the agreement were followed.

Indian Workers in the Caribbean

After slavery ended, European sugar colonies in the West Indies tried using former slaves, families from Ireland, Germany, Malta, and Portuguese people from Madeira. These efforts did not meet the colonies' labor needs. Many new arrivals died, and others did not want to keep working after their contracts ended.

On November 16, 1844, the British Indian Government made it legal to send workers to Jamaica, Trinidad, and Demerara (Guyana). The first ship, the Whitby, left Calcutta for British Guiana on January 13, 1838. It arrived in Berbice on May 5, 1838. Sending workers to the Caribbean stopped in 1848 due to problems in the sugar industry. It started again in Demerara and Trinidad in 1851, and in Jamaica in 1860.

Bringing in indentured workers became profitable for plantation owners. This was because newly freed slaves refused to work for very low wages. For example, Jamaica had 322,000 freed slaves, while British Guiana had about 90,000. The British also had a political reason to bring in foreign workers. More Indian workers reduced the power of the freed slaves to demand better pay. This made their position weaker in the plantation system.

Encouraging Workers to Stay Longer

Giving Up Free Passage

European planters constantly pushed for longer work contracts. To encourage workers to stay, the Mauritius Government offered £2 to any worker who stayed and gave up their free return trip in 1847. The Mauritius Government also wanted to stop offering return passages.

Finally, on August 3, 1852, the British Indian Government agreed to change the rules. If a return passage was not claimed within six months, it would be lost. But there were protections for the sick and poor. Another change in 1852 said workers could return after five years if they paid $35 for the trip. They would get a free return trip after 10 years. This change made fewer people want to sign up for 10 years, and $35 was too expensive. So, this rule was stopped after 1858.

Increasing Women Workers

It was thought that if workers had families in the colonies, they would be more likely to stay. The number of women in early migrations to Mauritius was small. The first effort to fix this was on March 18, 1856. The Secretary for the Colonies told the Governor of Demerara that women must make up 25 percent of the total workers for 1856–57. In later years, the number of men could not be more than three times the number of women.

It was harder to convince women from North India to go overseas than those from South India. But the Colonial Office kept trying. On July 30, 1868, instructions were given that there should be 40 women for every 100 men. This rule stayed in place for the rest of the indenture period.

Offering Land Grants

Trinidad tried a different approach. The government offered workers a reason to settle there after their contracts ended. From 1851, £10 was paid to those who gave up their return passages. This was later replaced by offering land. In 1873, more incentives were given: 5 acres of land plus £5 cash.

Also, Trinidad passed a law in 1870. It said that new immigrants would not be sent to plantations where the death rate was higher than 7 percent.

Recruitment for Other European Colonies

The success of the Indian indenture system for the British, despite its human cost, was noticed by others. Other European plantation owners started setting up agents in India to recruit workers. For example, French sugar colonies hired workers through French ports in India without the British authorities knowing. By 1856, about 37,694 workers were in Réunion.

It was not until July 25, 1860, that the British officially allowed France to recruit 6,000 workers annually for Reunion. This was expanded on July 1, 1861. Permission was given to bring "free" laborers to the French colonies of Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Guiana (Cayenne). The contracts were for five years (longer than British colonies at the time). A return passage was provided at the end of the contract. The Governor-General could stop emigration to any French colony if abuses were found.

Danish plantation owners also started bringing Indian workers to St. Croix. However, this indenture system did not last long.

Indenture to Other British Empire Parts

After new labor laws were accepted by the British Government of India, the indenture system was extended to smaller British Caribbean islands. These included Grenada in 1856, St Lucia in 1858, and St Kitts and St Vincent in 1860.

Sending workers to Natal (now part of South Africa) was approved on August 7, 1860. The first ship from Madras arrived in Durban on November 16, 1860. This formed the basis of the Indian South African community. These workers signed three-year contracts.

The British Government allowed transportation to the Danish colonies in 1862. There was a high death rate on one ship sent to St Croix. After bad reports from the British Consul about how indentured workers were treated, further emigration was stopped. The survivors returned to India in 1868, leaving about eighty Indians behind. Permission was given for emigration to Queensland in 1864, but no Indians were transported there under this system.

Improving the British Indian Labor System

There were many differences in the systems used for British Indian labor in various colonies. British Government regulations in 1864 tried to make things more uniform and reduce abuse. These rules included:

- Workers had to appear before a judge in their home district, not just at the port.

- Recruiters needed licenses, and faced penalties for breaking rules.

- Rules for the Protector of Emigrants were clearly defined.

- Rules for worker depots were set.

- Agents were paid a salary, not a commission.

- Rules for how emigrants were treated on ships were made.

- The ratio of females to males was set uniformly at 25 females for every 100 males.

Despite these efforts, the sugar colonies still made labor laws that were unfair to immigrants. For example, in Demerara, a law in 1864 made it a crime for a worker to be absent from work, misbehave, or not complete five tasks each week. New labor laws in Mauritius in 1867 made it hard for workers whose contracts ended to leave the plantation system. They had to carry passes showing their job and district. Anyone found outside their district could be arrested and sent to an Immigration Depot. If they had no job, they were considered homeless.

Transportation to Suriname

Sending Indian workers to Suriname began under a special agreement. In exchange for the Dutch right to recruit Indian labor, the Dutch gave some old forts in West Africa to the British. They also agreed to end British claims in Sumatra. Workers signed up for five years and were given a return trip home. However, they were subject to Dutch law. The first ship carrying Indian indentured workers arrived in Suriname in June 1873. Six more ships followed that same year.

Indian Workers in British and French Colonies (1842-1870)

After slavery was abolished in the British Empire, it was also ended in the French colonial empire in 1848. The U.S. abolished slavery in 1865.

Between 1842 and 1870, a total of 525,482 Indians moved to British and French Colonies.

- 351,401 went to Mauritius.

- 76,691 went to Demerara.

- 42,519 went to Trinidad.

- 15,169 went to Jamaica.

- 6,448 went to Natal.

- 15,005 went to Réunion.

- 16,341 went to other French colonies.

These numbers do not include the 30,000 who went to Mauritius earlier, or workers who went to Ceylon or Malaya. It also doesn't include illegal recruitment to French colonies. By 1870, the indenture system was a well-established way to provide workers for European colonial plantations. When Fiji started receiving Indian workers in 1879, it used this same system with only small changes.

The Indenture Agreement (1912)

Here are some key parts of a typical indenture agreement from 1912:

- Service Period: Five years from the day they arrived in the colony.

- Work Type: Labor related to farming or making products on any plantation.

- Work Days: Every day, except Sundays and official holidays.

- Daily Hours: Nine hours on each of five days a week (Monday to Friday), and five hours on Saturday. No extra pay for these hours.

- Wages:

- For time-work: Adult male workers (over 15) got at least one shilling (about twelve annas) per nine-hour workday. Adult female workers (over 15) got at least nine pence (about nine annas). Children got paid based on how much work they did.

- For task-work: Adult male workers (over 15) got at least one shilling per task. Adult female workers (over 15) got at least nine pence per task. A man's task was what an average strong man could do in six hours. A woman's task was three-fourths of a man's task. Employers didn't have to give more than one task, and workers didn't have to do more. But they could agree to extra work and pay.

- Wage Payment: Wages were paid weekly on Saturday.

- Return Passage: Workers could return to India at their own cost after five years of working in the colony. After ten years of continuous living in the colony, if they had completed five years of work, they could get a free return passage. They had to claim it within two years after the ten years. If a worker was under twelve when they arrived, they could get a free return passage before age 24 if they met other conditions. A child born in the colony could get a free return passage until age twelve, but had to travel with parents or a guardian.

- Other Conditions:

- Workers got food from their employers for the first six months. This cost four pence (about four annas) per day for those twelve and older.

- Children aged five to twelve got about half rations for free. Children under five got milk daily for free during their first year.

- Workers got suitable housing for free, and employers kept it in good repair.

- If workers got sick, they received hospital care, medical attention, medicines, and food for free.

- A worker with a living wife could not marry another wife in the colony unless their first marriage was legally ended. But if they had more than one wife in India, they could bring them all, and they would be legally recognized.

End of the Indenture System

Gopal Krishna Gokhale, an Indian leader, proposed a bill in February 1910 to stop sending indentured workers to Natal (now South Africa). The bill passed easily and took effect in July 1911. However, the British-led Indian indenture system for other colonies finally ended in 1917. According to The Economist, the system ended due to pressure from Indian nationalists and because it was becoming less profitable, not mainly because of humanitarian concerns.

Indian Indentured Workers by Colony (1842-1870)

| Name of Colony | Number of Labourers Transported |

|---|---|

| British Mauritius | 453,063 |

| British Guiana | 238,909 |

| British Trinidad and Tobago | 147,596 |

| British Jamaica | 36,412 |

| British Malaya | 400,000 |

| British Grenada | 3,200 |

| British Saint Lucia | 4,350 |

| Natal | 152,184 |

| Saint Kitts | 337 |

| Nevis | 315 |

| Saint Vincent | 2,472 |

| Réunion | 26,507 |

| Dutch Surinam | 34,304 |

| British Fiji | 60,965 |

| East Africa | 32,000 |

| Seychelles | 6,315 |

| British Singapore | 3,000 |

| Danish West Indies | 321 |

| Total | 1,601,935 |

Cultural Impact

Writers of Indian descent from the Caribbean have greatly influenced the literature of that region. In Guyana, Indo-Guyanese writers like Joseph Rahomon and Shana Yardan have had a strong impact on Guyanese literature.

Nobel Prize winner V.S. Naipaul is of Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonian origin. His books often reflect his background and experiences.

Population Changes

This migration caused big changes in the populations of several countries.

- Where Indians became the majority or biggest group:

- Mauritians of Indian origin: 65.00% of the population in Mauritius.

- Indo-Guyanese: 39.83% of the population in Guyana.

- Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonian: 35.43% of the population in Trinidad and Tobago.

- Indo-Surinamese: 27.40% of the population in Suriname.

- Where Indians became the second largest group:

- Indo-Fijians: 37.50% of the population in Fiji.

- Indo-Grenadians: 11% of the population in Grenada.

- Indo-Martiniquais: 10% of the population in Martinique.

- Significant minority groups:

- Indian Singaporeans: 9.00% of the population in Singapore.

- Malaysian Indians: 7.00% of the population in Malaysia.

- Indian South Africans: 2.60% of the population in South Africa.

- Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka: 4.2% of the population in Sri Lanka.

- Other groups, including significant minorities in the past or economically strong minorities:

- Indians in Uganda

- Demographics of French Guiana

- Réunionnais of Indian origin

- Indo-Caribbeans

See Also

- Coolie

- Global Girmit Museum