Irrigation in viticulture facts for kids

Irrigation in viticulture means giving extra water to grapevines. It's a bit controversial but also super important for making wine. Water helps grapevines grow and make grapes. It's key for photosynthesis, which is how plants make their food. A typical grapevine needs about 25-35 inches (635-890 millimeters) of water each year. This water is needed during spring and summer, which is the growing season. If a vine doesn't get enough water, it can get "stressed." Sometimes, a little water stress is good for wine grapes, making the berries smaller and sweeter.

In many Old World wine regions (like parts of Europe), people believe that only natural rainfall should water the vineyards. They think this helps keep the unique terroir (the special qualities of a place) of the wine. Some critics worry that irrigation can make vineyards produce too many grapes, which might lower the wine's quality. Historically, the European Union's wine laws banned irrigation. But recently, countries like Spain and France are starting to allow it more.

In very dry places with little rain, irrigation is a must for growing grapes. Many New World wine regions, such as Australia and California, use irrigation regularly. Without it, they couldn't grow grapes at all. Research in these areas, and places like Israel, shows that careful irrigation can actually improve wine quality. This is often done by controlling "water stress." Vines get enough water during budding (when buds appear) and flowering (when flowers bloom). Then, irrigation is reduced during the ripening period. This makes the vine focus its energy on developing the grape clusters instead of growing too many leaves. If a vine gets too little water, it can shut down, affecting its growth and nutrient storage. Irrigation helps make sure vines get enough water, even during drought, keeping them healthy.

Contents

History of Irrigation in Vineyards

Giving water to plants has a very long history in wine production. Archaeologists have found irrigation canals near vineyards in Armenia and Egypt that are over 2600 years old! People were already using irrigation for other farm crops around 5000 BC. It's possible that this knowledge helped grape growing spread to new places. Grapevines are tough plants. They mostly need lots of sunshine and can grow well with little water and nutrients. In places where natural water was scarce, irrigation made it possible to grow grapes.

In the 1900s, new ways of irrigating helped the wine industries in California, Australia, and Israel grow a lot. It became cheaper and easier to water vines. This meant huge dry, sunny areas could become wine regions. Being able to control the exact amount of water each vine received helped winemakers in these "New World" regions make wines that tasted similar every year. This was different from "Old World" European wines, where the weather, including rainfall, greatly changed the wine each year.

Scientists kept studying how controlled irrigation could improve wine quality. They learned that by managing water, they could influence how grapevines developed their sugars, acids, and other important parts that make wine taste good. This research led to ways to measure how much water is in the soil. This helps vineyards plan exactly when and how much to water their vines.

How Water Helps Grapevines

Water is super important for all plants to live. For a grapevine, water acts like a taxi, carrying nutrients and minerals from the soil to all parts of the plant. Without enough water, the vine's roots struggle to absorb these nutrients. Inside the plant, water moves through tubes called xylem, delivering nutrients everywhere. During photosynthesis, water mixes with carbon from carbon dioxide to create glucose, which is the vine's main energy source. It also produces oxygen as a byproduct.

Grapevines also lose water through evaporation and transpiration. Evaporation is when heat (from wind and sunlight) turns water in the soil into vapor. This happens faster in dry, low-humidity areas. Transpiration is when the vine itself releases water vapor from tiny holes called stomata on its leaves. This water loss helps pull water up from the roots. It also helps the vine stay cool, much like how sweating cools humans. If a vine has enough water, its leaves stay only a few degrees warmer than the air. But if it lacks water, the leaves can get much hotter, causing heat stress. The combined effect of evaporation and transpiration is called evapotranspiration. A vineyard in a hot, dry place can lose a lot of water this way during the growing season.

What Influences Irrigation Needs?

There are two main types of irrigation. Primary irrigation is needed in very dry places where there isn't enough rain for grapes to grow at all. Supplemental irrigation is used to add extra water when natural rainfall isn't quite enough. It also helps prevent problems during dry spells. In both cases, the climate and the vineyard soils play a big role in how irrigation is used.

How Climate Affects Water Needs

Grapevines usually grow in Mediterranean, continental, and maritime climates. Each climate has its own challenges for providing water.

- Mediterranean Climates: These areas often need irrigation during the very dry summer ripening stages. Places with low humidity, like parts of Chile and South Africa, have high evapotranspiration, meaning vines lose a lot of water. So, primary irrigation might be needed. In other Mediterranean areas, irrigation is usually supplemental. For example, Tuscany gets enough spring rain for healthy grapes. But Napa Valley in California gets much less rain in spring, so supplemental irrigation is often necessary.

- Continental Climates: These are usually inland, away from large bodies of water. They have big temperature differences between summer and winter. Rain often falls in winter and early spring. If the soil holds water well, the vine might get enough water for the whole growing season. But if the soil doesn't hold water well, some supplemental irrigation might be needed in the dry summer. Examples include the Columbia Valley in Washington State and the Mendoza wine region in Argentina.

- Maritime Climates: These climates are moderate because they are near large bodies of water. The humidity affects how much irrigation is needed. Often, irrigation is only supplemental during dry years. Many maritime regions, like Bordeaux in France, sometimes have the opposite problem: too much rain during the growing season!

How Soil Affects Water Needs

Soil is very important for wine quality. While scientists aren't sure exactly how soil gives wine its unique terroir, they agree that how well soil holds and drains water is key. Water retention is the soil's ability to hold water. Drainage is how easily water moves through the soil. The best soil holds enough water for the vine but also drains well so the roots don't get waterlogged. Soil that doesn't hold water well can cause vines to get stressed. Soil that doesn't drain well can lead to waterlogged roots, which can be attacked by tiny living things that steal nutrients from the vine.

The depth, texture, and composition of soil affect how it holds and drains water.

- Soils with lots of organic material (like deep loams) hold the most water. These are found in fertile valley floors, like Napa Valley.

- Clay soils can also hold a lot of water, like the clay soils in Pomerol in Bordeaux. Many regions with these soils need little or no irrigation.

- Soils that don't hold water well include sand and alluvial gravel soils. These are found in places like Barolo in Italy or parts of South Australia. Depending on the climate, these areas might need irrigation.

Too much water is also bad for grapevines. Waterlogged vines can be attacked by bacteria and fungi that compete for soil nutrients. Wet soils are also cold soils. This can be a problem during flowering, leading to poor berry set. It's also an issue during ripening in cool areas, where vines need heat from the ground to ripen fruit. So, well-draining soils are great for making quality wine. Light soils (like sand and gravel) and stony soils usually drain well. Heavy soils with lots of organic matter can also drain well if they have a crumbly texture, often thanks to earthworms that create tunnels for water to pass through.

Checking Soil Moisture

Because too much water can be harmful, grape growers need to know how much water is in the soil before they irrigate. Simple observation can help, but it's hard to tell if the deeper soil is wet when the surface looks dry. More accurate tools are used today:

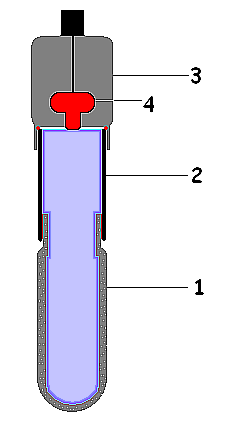

- Tensiometers measure the pull of water in the soil.

- Neutron moisture meters use a special tube to detect changes in water in the soil.

- Gypsum blocks with electrodes measure electrical resistance as the soil dries.

- Newer tools use time-domain reflectometry and capacitance probes.

Besides checking for too much moisture, growers also look for signs of water stress (when the vine doesn't have enough water).

Types of Irrigation Systems

There are different ways to irrigate vineyards, depending on how much control is needed.

- Surface Irrigation: Historically, this was common. Water was flooded across the vineyard using gravity. In Chile, melted snow from the Andes Mountains was channeled to vineyards. This method offered little control and often over-watered the vines. A slightly better version was furrow irrigation in Argentina, where small channels ran through the vineyard. This allowed some control over the initial water, but each vine still got a different amount.

- Sprinkler Irrigation: This involves sprinklers placed throughout the vineyard, often about 65 feet (20 meters) apart. They can be set on a timer to release a specific amount of water. This gives more control than flood irrigation and uses less water, but individual vines still get varying amounts.

- Drip Irrigation: This system offers the most control, though it's the most expensive to install. Long plastic lines run down each row of vines, with each vine having its own dripper. A grower can control the exact amount of water each grapevine gets, down to the drop. A variation is subirrigation, where water is delivered directly to the roots underground. This can be useful where irrigation is restricted.

When to Irrigate?

If a grapevine has too much water, it will grow shallow roots and lots of new shoots and leaves. This can lead to many large grape clusters that might not ripen well. If it has too little water, important processes like photosynthesis can shut down. The goal of irrigation is to give just enough water for the plant to function without encouraging too much growth. The exact amount depends on natural rainfall and the soil's water-holding ability.

Water is very important during the early budding and flowering stages in spring. If there's not enough rain, irrigation might be needed then. After fruit set (when grapes start to form), the vine needs less water. Irrigation is often stopped until veraison (when grapes change color). This period of "water stress" makes the vine focus its energy on producing fewer, smaller berries. Smaller berries have a better skin to juice ratio, which is good for quality wine.

Whether to irrigate during ripening is still debated. However, most agree that watering right before harvest after a long dry spell is bad. Vines that have been very thirsty will quickly soak up a lot of water. This can make the berries swell and crack, making them prone to diseases. Even if they don't crack, the sudden water intake dilutes the sugars and flavors, leading to wines with weaker tastes and aromas.

Water Stress in Grapevines

Water stress is what happens to grapevines when they don't get enough water. When a vine is stressed, it first slows down the growth of new shoots, which compete with the grapes for resources. The lack of water also keeps the grape berries smaller, which increases their skin-to-juice ratio. Since the skin holds much of the wine's color, tannins, and aroma compounds, a higher skin-to-juice ratio is often good for complex wines. Most grape growers agree that some water stress can be helpful. Many vineyards in Mediterranean climates, like Tuscany in Italy and the Rhone Valley in France, naturally experience water stress due to less summer rain.

However, severe water stress can harm the vine and the wine. To save water, a vine will try to close the stomata (tiny pores) on its leaves. This reduces water loss but also limits the carbon dioxide needed for photosynthesis. If the stress continues, photosynthesis can stop completely. If a vine is too deprived of water, it can reach its permanent wilting point, meaning it's permanently damaged even if watered later. Growers carefully watch for signs of severe water stress, such as:

- Drooping tendrils

- Dried-out flower clusters

- Wilting of young leaves, then older leaves

- Yellowing leaves (chlorosis), meaning photosynthesis has stopped

- Dying leaf tissue (necrosis), leading to leaves falling off early

- Finally, grapes shriveling and falling off

Scientists are still researching the best level of water stress. They are also studying how water stress affects white grape varieties, with some experts believing it can reduce their aromatic qualities.

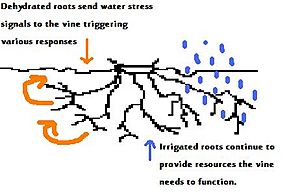

Partial Rootzone Drying

Partial rootzone drying (PRD) is a clever irrigation trick. It makes the grapevine think it's stressed, even though it's getting enough water. This is done by watering only one side of the vine's roots at a time. The dry roots send signals to the vine, triggering responses like slower shoot growth and smaller berries. But because the other side of the vine is still getting water, the stress isn't so severe that important functions like photosynthesis stop. PRD helps vines use water more efficiently. It might slightly reduce leaf area, but it usually doesn't affect the overall grape yield.

Criticism and Environmental Concerns

Irrigation has its critics and environmental worries. In many European wine regions, it was banned because people thought it hurt wine quality. However, some European countries have recently relaxed their rules.

One common criticism is that irrigation messes with the natural terroir of the land. It also reduces the unique differences that come from vintage variation (how wines change year to year based on weather). Critics say irrigation contributes to the "standardization" of wine, making wines taste too similar globally.

There are also environmental concerns. Irrigation uses a lot of water, putting a strain on global water resources. While drip irrigation has reduced water waste, watering huge areas, like in California's San Joaquin Valley or Australia's Murray-Darling Basin, still requires massive amounts of water from shrinking supplies. In Australia, old flood irrigation methods caused severe environmental damage, including waterlogging and increased salt in the soil. Governments are now investing in research to reduce this damage.

Other Uses for Irrigation Systems

Besides providing water, irrigation systems can be used for other things:

- Fertigation: This is when fertilizer is mixed with the water and delivered to the vines. Drip irrigation systems are great for this, allowing precise control over how much fertilizer each vine gets.

- Frost Protection: Sprinkler systems can protect vines from frost in winter or spring. When temperatures drop below freezing (32°F or 0°C), frost can damage or even kill the vine. Sprinklers can spray water onto the vines, which then freezes into a protective layer of ice. This ice acts like insulation, keeping the vine's internal temperature from dropping below freezing.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |