John Forbes and Company facts for kids

John and Thomas Forbes were Scottish traders who worked in Florida and the nearby areas in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Their company, John Forbes & Company, took over from another trading firm called Panton, Leslie & Company after its leaders, William Panton and John Leslie, passed away in the early 1800s.

When the trade in animal hides and supplies slowed down, especially during the War of 1812 and the Creek War, Forbes & Company looked for ways to get back the money they had lost. They tried suing British officers and talking with Native American tribes. The Creek and Seminole people gave large areas of land to the company to pay off their debts. The Spanish governor of Florida approved these land transfers.

This land, known as the Forbes Purchase, was over 1.4 million acres. Forbes & Company acquired it between 1804 and 1812. It was the biggest land grant in Spanish Florida at the time. In 1817, the Forbes Purchase was sold to two merchants, Carnochan and Mitchel, who later started the Apalachicola Land Company. Even in territorial Florida (from 1821 to 1845), who owned the land near the Apalachicola River was not fully decided until 1835. Lawsuits about land claims in the Florida Panhandle by the family of Thomas Forbes continued as late as 1887.

Contents

The Forbes Family Story

Thomas and John Forbes were the sons of James and Sarah Gordon Forbes, who lived in Banff, Scotland. John was born around December 20, 1767, and passed away in Matanzas, Cuba, on May 13, 1823. Thomas's birth date is unknown, but he died in 1808. They also had two sisters, Anne and Sophia. Sophia's husband, Alexander Glennie, also worked in international trade, just like Thomas and John.

Records suggest that John Forbes never married, but he had children with a woman named Marie Isabelle Narbonne in Mobile, Alabama. Around 1818, John Forbes and his family moved to an estate in Matanzas, Cuba. There, he ran a sugar mill with his sons-in-law. Marie Narbonne died in 1822. John Forbes himself passed away from a sickness on May 13, 1823, while sailing to New York.

Thomas Forbes married Elizabeth Anne Yonge in the Bahamas in 1789. They had four children: William Henry, John Gordon, Mary Sophia, and Thomas Irving Forbes. Some of Thomas Forbes's descendants later sued the companies that took over from John Forbes and Company. They wanted to get back money for lands the company had originally owned.

Early Trading Companies in Florida

Thomas Forbes, the older brother, likely arrived in Charles Town, South Carolina, before the American Revolution. There, he began to meet the people who would become his trading partners in Panton, Leslie and Company. His uncle, John Gordon, had arrived around 1760.

John Gordon and Company hired William Panton as a clerk in 1765. This company imported goods from Europe, selling them to colonists and trading them with the Cherokee and Creek (Muscogee) nations. These Native American nations controlled land west and south of the Southern colonies. In 1772, Gordon made Panton one of his legal representatives. Another future partner, John Leslie, also from Scotland, started trading in the Charleston area before 1779, but he mainly did business in East Florida.

Just before John Forbes arrived, all the older companies closed down. In 1783, William Panton, John Leslie, Thomas Forbes, William Alexander, and Charles McLatchy formed Panton, Leslie and Company. This new company grew into Florida and became the main trading company with Native American groups from St. Augustine to Pensacola. In 1784, John Forbes sailed from Scotland to the Bahamas, where the company had docks and warehouses. Then he went to St. Augustine, which was the company's main office in East Florida. Soon after, he was sent to help William Panton at the West Florida office and manage the store in Mobile, West Florida. (Alabama did not become a U.S. territory until 1817.)

Panton, Leslie and Company and the companies that followed them were involved in a type of trade called the triangular trade. They brought manufactured goods to Africa by ship. There, these goods were exchanged for people who were then forced to travel across the Atlantic to the West Indies and the Thirteen Colonies to be sold to plantation owners, including some Creek Indian chiefs. Rum, sugar, salt, and indigo were bought in the West Indies and brought to North America. Other goods, like firearms, gunpowder, and lead bullets, were traded with Native Americans for deer hides and furs. Hides, cotton, tobacco, sugar, rum, and rice were then taken back to Europe and sold to buy more goods for the next trading trip.

All the partners of Panton, Leslie and Company were Scots who remained loyal to Britain during the Revolutionary War. They were called "Tories" by the colonists. This decision made sense for their business because their trade depended on manufactured goods that could not be made in the colonies. The partners were attacked by American Patriots and were even called traitors by the Committee for Safety in South Carolina. Because it was dangerous to stay in the rebelling colonies, the partners moved to St. Augustine, Florida, in 1776. St. Augustine was a safe place for loyalists until the British government gave the territory back to Spain in the 1783 Peace of Paris.

William Panton and Thomas Forbes worked closely with the Governor of East Florida, Patrick Tonyn. Their trading company operated from East Florida and Nassau in the Bahamas. They gained trading posts along the St. Mary's and St. Johns rivers and plantations that grew indigo, rice, tobacco, and cotton. The company sometimes brought in enslaved people from Africa to work on the plantations or to be sold to other owners. Thomas also managed a very successful business in the Bahamas.

When the Revolutionary War ended, the British government gave East and West Florida (which was already under Spanish control) to Spain. The new Spanish governors saw trade with Native Americans as a key way to control the territory. They soon learned that the Creeks, in particular, preferred to deal with Panton, Leslie and Company. The partners gained status as agents of the Spanish Crown and were given almost complete control over trade. Pensacola soon became the busiest trading center, and Panton, Leslie and Company moved its main office from St. Augustine to Pensacola.

Trade with Creek and Seminole People

A big reason Panton, Leslie and Company controlled trade with the Creek people was the help of a Creek chief named Alexander McGillivray. He was the son of a Scotsman, Lachlan McGillivray, and a half-Creek woman named Sehoy Marchand. Alexander studied in Charleston before the Revolutionary War and worked in a trading house in Savannah. However, he returned to Creek lands before the war and became a British representative. Because Patriot troops had taken his lands in Georgia, he stayed loyal to Britain and preferred to trade with Panton, Leslie and Company. In 1783, McGillivray was named a head warrior of the Creek nation.

Panton, Leslie & Company set up its main office in Pensacola, West Florida. They also had other trading houses in Mobile and St. Marks, Florida. From these places, goods could be carried into Creek and Seminole lands by boat and by pack animals. Deer hides were the main item traded between the Creeks and the company. This was partly because there was a high demand for leather in Europe when cattle diseases reduced leather supplies.

Hides and furs brought in by Native Americans were exchanged for woolen goods, cotton and linen cloth, handkerchiefs, leather shoes, saddles and bridles, rifles and muskets, gun flints, bullets, brass and tin kettles, axes, metal pots and pans, scissors, fishhooks, tobacco, and pipes. However, gunpowder was always the most important item for trade.

Native Americans in the Southeast had started trading with Spanish, English, and French people in the 1600s. None of the tribes had developed the ability to make cloth, iron goods, or glass. Firearms became essential not only for getting deer hides but also for defending tribal lands against rivals and settlers from the American colonies. All the southeastern Native Americans became dependent on manufactured goods. Traditional skills, like making stone-tipped knives and arrows, became less common. Like the Cherokee, Creeks adopted many European customs, including living in stable villages with farms that grew corn, beans, squash, melons, and cotton. They also started raising cattle and hogs.

After William Panton died in 1801, John Leslie went back to London to manage the company's business. In July 1803, "John Forbes and Company" appeared in the company's records. In 1804, it officially replaced Panton, Leslie and Company. During this time, partners in Florida, including John and James Innerarity and interpreter William Hambly, tried to get payments from Native Americans for unpaid debts.

From 1804 to 1817, John Forbes and Company was the main trading company with Native Americans in Spanish Florida. However, it was hard to make a profit during the War of 1812, the Creek War, and the first Seminole Wars. Spanish leaders, including Governor Vicente Folch, allowed the company to trade without paying taxes. This was a way to stop American fur traders from coming into the area. James Innerarity and Edmund Doyle opened a new store at Prospect Bluff, about 20 miles north of the Apalachicola River mouth. James also managed the store in Mobile, which was still in West Florida, even though the United States claimed it was part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

John Forbes and Company operated in West Florida under the protection of the Spanish government. When the United States took over Mobile and part of West Florida in 1814, Forbes and his partners, James and John Innerarity, said they were Spanish citizens because they lived there. They got official papers from the Spanish governor confirming this. The men adopted Spanish names and likely spoke Spanish very well. To help confirm Spain's right to own the territory, "Juan Forbes" wrote a book in 1804 called Descripción de las Floridas y medios de fomentarlas, which means John Forbes Description of the Spanish Floridas, 1804.

Land Given to the United States

Many Native American tribes that traded with Panton, Leslie & Company and John Forbes & Company lived on land between Georgia and the Mississippi River. This area became the Mississippi Territory in 1798 after Spain gave the land to the United States with the Treaty of Madrid. President Thomas Jefferson wanted to move Native American tribes to allow more settlers to move into the territory.

Benjamin Hawkins, a U.S. agent for Native Americans in Mississippi Territory, and John McKee, an agent in Tennessee, met with John Forbes. They talked about using Forbes & Company to help with the land transfers. Because the Creek (Muscogee), Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Cherokee tribes (along with the Seminoles, these were known as the five civilized tribes) owed money to Forbes & Company, the tribes might agree to give up land if the United States government paid their debts. This plan was discussed with U.S. General James Wilkinson, who then sent the idea to Henry Dearborn, the U.S. Secretary of War. In 1804, Forbes traveled to Washington to discuss the plan with Secretary Dearborn. He carried a letter of introduction from General Wilkinson to the Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

Forbes & Company successfully made agreements with the four tribes in 1805. The U.S. signed separate treaties with each tribe. The land transfers, which totaled about 8 million acres, were approved between 1805 and 1814. The Creeks gave up land in Georgia between the Oconee and Ocmulgee rivers. The Choctaw gave up land between the Alabama and Pearl rivers. The Chickasaw and Cherokee gave up their lands north of the Tennessee River. The United States paid Forbes & Company over $77,000 for their help.

The Forbes Land Grants

Even after helping the United States, John Forbes insisted that the Lower Creeks and Seminoles still owed his company a large amount of money. This was because of two robberies of the trading post on the Wakulla River in 1792 and 1800, which involved William Augustus Bowles. The company had also given credit to members of several tribes, including Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws. They claimed a total of over $192,000 was owed to them.

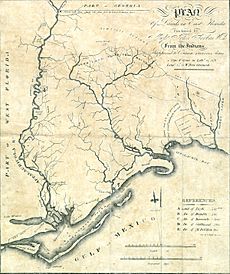

After John Leslie's death in 1803, Forbes sailed to London to officially change the company name from Panton, Leslie and Company to John Forbes and Company. Meanwhile, his partners, James and John Innerarity and William Hambly, talked with 24 Creek and Seminole chiefs about giving land as payment. Between 1804 and 1811, the company collected most of the debt. They were paid when the tribes gave land to the company, with the approval of the Spanish governor Vicente Folch y Juan. This transfer of land between the Apalachicola River and Wakulla River to the company became known as Forbes Grant I or the Forbes Purchase. It included over 1.4 million acres that stretched from the barrier islands of Apalachicola Bay to the Upper Sweetwater Creek in what are now Liberty and Leon Counties.

The Creek people agreed to give Forbes & Company their land only if the company would build a trading post on the Apalachicola River. In 1804, James Innerarity and Edmund Doyle built a post at Prospect Bluff, about 20 miles north of the river's mouth. The trading post had a building for storing hides, living quarters for enslaved people, and a pen for several hundred cattle raised nearby. During the War of 1812, British troops looted the store and freed the enslaved people. The losses during the war later caused the company to ask the Spanish governor for a second land grant. This became known as Innerarity's Claim or Forbes Grant II. This second claim included 1.2 million acres west of the Apalachicola River. However, it was overturned in Florida courts in 1830 when future Florida governor, Richard K. Call, found that the land transfer happened too late to be valid.

When it became impossible to make a profit from trade after the War of 1812–1814, Forbes decided to sell the land in Forbes Grant I. He likely saw that Spain and the United States would sign a treaty that might put his land claims at risk. So, in 1817, he sold the property to two merchants named Carnochan and Mitchel. Future lawsuits about the land would mainly involve them and James Innerarity, who still owned about 40,000 acres of the grant. The families of the partners continued to file lawsuits until their claim was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1906 in a case called United States vs. Dalcour.

After John Forbes left, James and John Innerarity continued to manage John Forbes and Company for several years. However, sales were mostly with American settlers rather than Creek people. In 1830, John Innerarity bought the remaining company assets in Pensacola. He then retired from the firm and closed the Pensacola store. The company's claim to land west of the Apalachicola River was denied by the courts. Their remaining Native American clients were forced to move west of the Mississippi River because of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. James continued managing the firm from Mobile, but John Forbes & Company ended when he died in 1847.

Carnochan, Mitchel and Company

John Forbes had tried to make money for his company by selling land to settlers. He also tried to get direct payments of cash or land from the Spanish government, but neither of these plans worked well. In December 1817, John Forbes sold most of the lands his company had acquired east of the Apalachicola River for $66,666. The buyers were two merchants from Savannah and Cuba named Richard Carnochan and Colin Mitchel. John Forbes and his partners kept about 25,000 acres for themselves, including Forbes Island in the Apalachicola River. An initial payment was to be made in London in 1818, and the remaining $50,000 was to be paid in yearly amounts. However, Forbes and his partners never received these payments.

The lands of the Forbes Purchase were given to Carnochan and Mitchel in the same year that John Quincy Adams and Luis de Onís began talking about Spain giving Florida to the United States. They signed the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819, and it was approved in 1821. Officially, Spanish land grants made before January 24, 1818, were supposed to be legal. However, they had to be confirmed by local or federal courts. The way to get official ownership for large grants like the Forbes Purchase was not set up by the U.S. Congress until 1828.

After selling the land, John Forbes slowly retired from company business. He died in Cuba in 1823. This left future disagreements about inheritances to Carnochan and Mitchel, James Innerarity, and many other family members who believed they had not received what they were promised when Panton, Leslie and Company and Forbes and Company closed down.

The Apalachicola Land Company

The first American settlers who moved into the territorial Florida Panhandle often lived on land they thought was public, but it was actually part of the Forbes grant. For example, Major Charles I. Jenkins, a U.S. customs collector, built a customs house on the west side of the Apalachicola River mouth. Other people who settled without permission joined him at a place called Cottonton or West Point, on land claimed by Forbes's successors.

The official ownership of Colin Mitchel and his partners' claim to the Forbes Purchase could not be confirmed right away. The partners planned a settlement called Colinton near their old trading post, several miles north on the river. However, most new people bypassed this town and built homes near the customs house at West Point. In 1821, James Grant Forbes (who was not related to John Forbes) included a map of Colinton and a description of the Forbes Purchase in his book about East Florida. Even though the land had a huge amount of untouched forest, most of the area was not good for farming or manufacturing.

In 1828, the U.S. Congress allowed people claiming Spanish land grants to file lawsuits in federal courts. Mitchel and his partners asked the U.S. District Court to confirm their claim. Their request was denied in 1830, so the partners appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In the last decision made by Chief Justice John Marshall, the court ruled in favor of Mitchel and his partners in 1835.

The partners then reorganized as the Apalachicola Land Company. They planned to raise money by selling land and lots in the town that had been renamed Apalachicola, Florida in 1831. Right after the favorable decision, the company hired Asa Hartfield to survey the area. This was to create documents that could prove land ownership. The first sale of lots in Apalachicola raised $443,800, but later sales decreased. A document from 1835 in Leon County, Florida, shows Thomas Baltzell, who would later become a Florida supreme court justice, as the President of the Apalachicola Land Co.

The future of the lands in the Forbes Purchase was never simple. Some residents bought lots and built homes. Others started a new town called St. Joseph on land that was not part of the Forbes Purchase. This town was about 20 miles northwest, next to a deep-water harbor on St. Joseph's Bay (see St. Joseph, Gulf County, Florida). Most residents moved back to Apalachicola after a yellow fever outbreak in 1841 caused many people to leave St. Joseph.

The Apalachicola Land Company continued trying to sell land from 1835 until the American Civil War. However, land sales never really took off. Without enough money, the company had to pay its debts and taxes by giving land to the people it owed money to. Also, the family members of Thomas Forbes felt they had been cheated out of their inheritance and filed a lawsuit in 1851. In 1855, John Beard was appointed to manage the company and tried to sell off the properties at auction. He gave his position to George Hawkins in 1866. Most of the land was sold for very little money per acre. The Apalachicola Land Company stopped existing, and many years of legal battles were needed to settle who owned the land and barrier islands near Apalachicola.

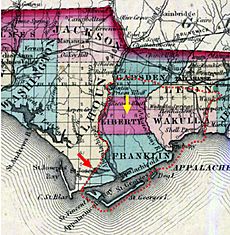

Forbes Purchase and Florida County Lines

When people from Apalachicola moved to St. Joseph, outside the Forbes Purchase, in 1835, they asked the Territorial Legislative Council to make St. Joseph the county seat of Franklin County. Although their request was denied, a new county called Calhoun was created from parts of Franklin County and Washington County in 1838. The western boundary of the Forbes Purchase became the county line between Calhoun and Franklin. This line still exists today as the boundary between Franklin and modern Gulf County.

When the family members of Thomas Forbes sued the Apalachicola Land Company in 1851, residents who lived in Gadsden County, in the northern part of the Forbes Purchase, worried they might lose ownership of their lands or face new taxes. The county representative suggested dividing Gadsden into two parts. Liberty County, in the southern central area, would contain most of the land from the Forbes Purchase. In 1855, Liberty County was formed by taking sections from Gadsden and Franklin counties. Gulf County was formed from Calhoun County in 1922 and follows the boundary of the Forbes Purchase. As a result, the Forbes Purchase continued to affect Florida's county boundaries and property sales long after the dispute was settled in 1887.