Marie Tharp facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marie Tharp

|

|

|---|---|

Marie Tharp in 1968

|

|

| Born | July 30, 1920 Ypsilanti, Michigan, U.S.

|

| Died | August 23, 2006 (aged 86) Nyack, New York, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Ohio University University of Michigan University of Tulsa |

| Known for | Seafloor topography |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geology, Oceanography |

| Institutions | Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory Columbia University |

Marie Tharp (born July 30, 1920 – died August 23, 2006) was an American geologist and oceanographer. She was also a mapmaker. In the 1950s, she worked with another geologist, Bruce Heezen. Together, they created the very first scientific map of the Atlantic Ocean floor.

Her detailed maps showed the ocean bottom in a new way. They revealed its mountains, valleys, and other features. Marie Tharp's biggest discovery was the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This is a huge underwater mountain range with a deep valley running through its center.

Her work changed how scientists understood the Earth. It helped prove the ideas of plate tectonics and continental drift. These theories explain how the Earth's outer layer is made of large moving plates.

Contents

Early life and education

Marie Tharp was born on July 30, 1920, in Ypsilanti, Michigan. She was the only child of Bertha Louise Tharp and William Edgar Tharp. Her mother taught German and Latin. Her father was a soil surveyor for the U.S. government.

Marie often went with her father on his field trips. This was her first introduction to mapmaking. However, she did not want to work in the field herself. At that time, field work was mostly for men.

Because of her father's job, her family moved often. By 1931, Marie had attended over 17 different schools. This made it hard for her to make friends. Her mother, who passed away when Marie was 15, was her closest friend.

A school year in Florence, Alabama, was very important for her. She took a class called Current Science. There, she learned about scientists and their projects. She also went on weekend trips to study trees and rocks.

After her father retired, Marie moved to a farm in Bellefontaine, Ohio. She finished high school there. She took a few years off before college to work on the family farm. In 1939, she started at Ohio University. She changed her main subject many times.

Marie graduated from Ohio University in 1943. She earned degrees in English and music. She also had four minor subjects.

During World War II, many young men left school to join the military. This meant more women were able to study subjects like petroleum geology. These fields were usually only for men. Marie had taken a geology class at Ohio. So, she went to the University of Michigan to study petroleum geology. She earned her master's degree in 1944.

After graduating, Tharp worked as a junior geologist at the Stanolind Oil company in Tulsa, Oklahoma. But she found that women were not allowed to do field work. She could only organize maps and data for her male co-workers. While working there, she also studied mathematics at the University of Tulsa. She earned her second bachelor's degree.

Career

By 1948, Marie Tharp wanted a new job. She moved to New York City. She looked for work at Columbia University. She found a job as a drafter for Maurice Ewing. He founded the Lamont Geological Observatory. This is now the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory. Marie Tharp was one of the first women to work there.

At Lamont, she met Bruce C. Heezen. They first worked together using photos to find military planes lost during World War II. Later, she worked only for Heezen, drawing maps of the ocean floor. Marie worked there from 1952 to 1968. After that, her job changed to be funded by grants. This was due to some issues at the lab. She stayed in a grant-funded role until Heezen passed away in 1977.

During the Cold War, the U.S. government did not want maps of the seafloor published. They were worried that Soviet submarines could use them.

For the first 18 years, Heezen gathered data on research ships. Women were not allowed on these ships at the time. So, Tharp drew maps from his data on land. Later, in 1968, she was able to join an expedition on the USNS Kane. She also used data from other research ships. Her work with Heezen was the first big effort to map the entire ocean floor.

Scientists had known about an underwater mountain range in the Atlantic since the mid-1800s. But Marie Tharp made a more accurate map of it. She used new data from an echo sounder. This device uses sound waves to measure depth. She discovered a deep rift valley running along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It took her a year to convince Bruce Heezen of this. Later, she mapped other mid-ocean ridges around the world.

Continental drift theory

Before the 1950s, scientists knew very little about the ocean floor. Studying land geology was easier. But to understand the Earth, they needed to know about the ocean floor too.

In 1952, Tharp carefully lined up depth measurements from different ships. She created about six maps showing the North Atlantic. From these, she saw the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. She noticed a V-shaped valley running through the middle of the ridge. She thought it might be a rift valley. This would mean the ocean floor was pulling apart.

Heezen did not believe her at first. This idea supported continental drift, which was a controversial theory. Many scientists, including Heezen, thought continental drift was impossible. He even called her idea "girl talk."

Heezen then hired Howard Foster to map where earthquakes happened in the oceans. When Foster's earthquake map was placed over Tharp's map of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, something amazing happened. The earthquakes lined up perfectly with Tharp's rift valley.

After seeing this, Tharp was sure that the rift valley existed. It was only then that Heezen accepted her idea. He then started to believe in plate tectonics and continental drift.

Tharp and Heezen published their first map of the North Atlantic in 1957. However, Tharp's name was not on some of the important papers about plate tectonics published by Heezen and others. Tharp kept working with students to map more of the central rift valley. She showed that the rift valley continued into the South Atlantic. She also found similar valleys in the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, and Red Sea. This suggested there was a global system of ocean rifts.

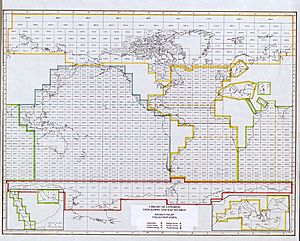

Later, Tharp and Heezen worked with artist Heinrich C. Berann. They created a map of the entire ocean floor. It was published in 1977 by National Geographic. Even though Tharp was later recognized, Heezen often received the main credit for the discovery at the time.

Retirement and death

After Heezen's death, Marie Tharp continued to work at Columbia University until 1983. Then, she ran a map-selling business in South Nyack. In 1995, she gave her map collection and notes to the Library of Congress.

In 1997, the Library of Congress honored her. They called her one of the four greatest mapmakers of the 20th century. Her work was also part of an exhibit. In 2001, Tharp received the first Lamont–Doherty Heritage Award. This was for her important work in oceanography. Marie Tharp passed away from cancer in Nyack, New York, on August 23, 2006. She was 86 years old.

Personal life

In 1948, Marie Tharp married David Flanagan. They moved to New York. They divorced in 1952.

Awards and honors

Like many scientists, Marie Tharp received most of her awards later in life. Her awards include:

- 1978 – National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal

- 1996 – Society of Woman Geographers Outstanding Achievement Award

- 1999 – Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Mary Sears Woman Pioneer in Oceanography Award

- 2001 – Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory Heritage Award

Legacy

In 1997, the Library of Congress recognized Tharp as one of the four greatest mapmakers of the 20th century. A special research position, the Marie Tharp Lamont Research Professor, was created in her honor.

Marie Tharp Fellowship

In 2004, Lamont created the Marie Tharp Fellowship. This is a special program for women scientists. It allows them to work with researchers at the Earth Institute of Columbia University. Women who are accepted can work with professors and students for three months. They also receive financial help.

Posthumous recognition

In 2009, Google Earth added the Marie Tharp Historical Map layer. This lets people see Tharp's ocean map using Google Earth.

A book about her life, Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor, was published in 2013.

She was also featured in an episode of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey. The episode showed her discovery of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It also highlighted how she overcame challenges as a woman in science.

Her life story is told in several children's books:

- Solving the Puzzle Under the Sea: Marie Tharp Maps the Ocean Floor by Robert Burleigh

- Ocean Speaks: How Marie Tharp Revealed the Ocean's Biggest Secret by Jess Keatting

- Marie's Ocean: Marie Tharp Maps the Mountains under the Sea by Josie James (This book won awards in 2021).

In 2015, the International Astronomical Union named a Moon crater "Tharp" in her honor.

In 2022, a research ship was named after her by the Ocean Research Project.

On November 21, 2022, Google honored Tharp with a special Google Doodle. It included stories, games, and animations about her discovery of continental drift.

Selected publications

- Tharp, Marie; Heezen, Bruce C.; Ewing, Maurice (1959). The floors of the oceans: I. The North Atlantic. 65. Geological Society of America. doi:10.1130/SPE65-p1.

- Heezen, B C; Bunce, Elizabeth T; Hersey, J B; Tharp, Marie (1964). "Chain and Romanche fracture zones". Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts 11 (1): 11–33. doi:10.1016/0011-7471(64)91079-4.

- Heezen, B C; Tharp, Marie (1965). "Tectonic fabric of the atlantic and indian oceans and continental drift". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A 258 (1088): 90–106. doi:10.1098/rsta.1965.0024.

- Tharp, Marie; Friedman, Gerald M (2002). "Mapping the world ocean floor". Northeastern Geology and Environmental Sciences 24 (2): 142–149..

See also

In Spanish: Marie Tharp para niños

In Spanish: Marie Tharp para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |