Mexican featherwork facts for kids

Mexican featherwork, also known as "plumería", was a very important art form in what is now Mexico. This art was popular before the Spanish arrived and continued during the colonial period. People in other parts of the world also valued feathers and made art with them. But the featherwork made by the amanteca (specialists in feather art) in Mexico truly amazed the Spanish conquerors. This led to new ideas being shared between Mexico and Europe. Feather pieces in Mexico started to use European designs, and feather art became very popular in Europe.

The best time for this art was just before the Spanish conquest and for about 100 years after. In the early 1600s, this art started to decline. This happened because the old masters died, birds that provided the best feathers became rare, and people started to value native crafts less. Featherwork, especially "mosaics" or "paintings" of religious images, was still known in Europe until the 1800s. But by the 1900s, it had mostly become a simple craft. Today, feather objects are often made for traditional dance costumes. You can also find feather mosaics in Michoacán and feather-trimmed huipils (traditional dresses) in Chiapas.

Contents

Ancient Featherwork in Mesoamerica

People all over the world have used feathers for decoration. In the New World, feathers were used for ceremonies and to show a person's rank, especially in clothing in places like Brazil and Peru. In Mesoamerica (an ancient region including parts of Mexico and Central America), feather use became very advanced. Some of the most detailed examples come from central Mexico.

Feathers were important because of their symbolic and religious meaning. This meaning grew with the worship of Quetzalcoatl, a god/king often shown as a serpent covered in quetzal feathers. Quetzalcoatl was said to have found gold, silver, and precious stones. The main Aztec god, Huitzilopochtli, was linked to the hummingbird. He was born from a ball of fine feathers that fell on his mother.

Feathers were as valuable as jade and turquoise in Mesoamerica. People believed they had magical powers, symbolizing fertility, wealth, and power. Those who used them were thought to have divine connections. We know feathers were used as far back as the Mayas, seen in their murals at Bonampak. The Mayans even raised birds for their feathers.

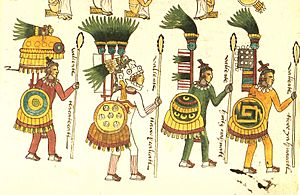

The most advanced use of feathers was among the Aztecs, Tlaxcaltecs, and Purépecha. Feathers were used for many things, like arrows, fans, fancy headdresses, and fine clothes. By the time of the Aztec ruler Ahuitzotl, richer feathers from tropical areas came to the Aztec Empire. The most beautiful feathers, like those from quetzals, were used during Moctezuma's rule. Featherwork covered ceremonial shields and the clothes of Aztec eagle warriors. Idols and priests also wore feather decorations.

Feathers came from local birds and from faraway places, especially in the Aztec Empire. They were taken from wild birds, as well as from domesticated turkeys and ducks. The best feathers came from Chiapas, Guatemala, and Honduras. These feathers were obtained through trade and as tribute (payments). Feathers were even used as a type of money, like cocoa beans. They were easy to carry over long distances, making them popular for trade. Some areas had to pay tribute in raw feathers, while others paid in finished feather goods. Cuetzalan paid tribute to Moctezuma with quetzal feathers. This demand was so high that quetzals became locally extinct in that area.

The most important feathers in central Mexico were the long green feathers of the resplendent quetzal. These were saved for gods and the emperor. Quetzals could not be kept as pets because they died in captivity. Instead, wild birds were caught, their feathers were plucked, and then they were released. Other tropical birds were also used. Bernardino de Sahagún listed many bird species used for fine feathers. Many of these are now endangered or no longer found in those areas.

In Aztec society, the artists who made feather objects were called the amanteca. They lived and worked in the Amantla neighborhood of Tenochtitlan. The amanteca had their own god, Coyotlinahual, and honored other deities. Daughters of amanteca often became embroiderers and feather dyers. Boys learned to make feather objects. The amanteca were a special class of craftsmen. They did not have to pay tribute or do public service. They had a lot of freedom in how they ran their businesses. Featherwork was so highly valued that even sons of noble families learned some of it. The amazing skill of this art can be seen in pieces made before the Spanish Conquest. Some of these are in the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna, like Montezuma's headdress.

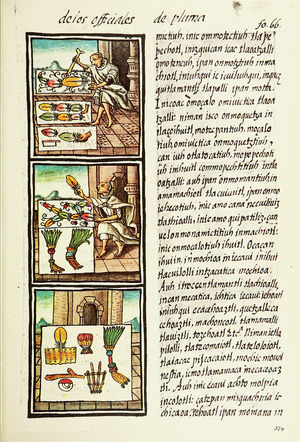

The Florentine Codex tells us how feather works were made. The amantecas used two main methods. One was to attach feathers using agave cord for 3D objects like fans and headdresses. The second, and harder, method was a mosaic-like technique, which the Spanish called "feather painting." These were mostly made for feather shields and cloaks for idols. Feather mosaics were made from tiny pieces of feathers from many birds. They were usually put on a base of paper made from cotton and paste, then backed with amate paper. These works were made in layers, with "common" feathers, dyed feathers, and then precious feathers on top. The glue for the feathers was made from orchid bulbs.

Sometimes feathers were dyed, or fine lines and dots were painted on them. In some of the most precious Aztec art, feathers were combined with gold and jewels. Feather art needs to be protected from light, which fades colors, and from insects that eat them.

Another way feathers were used was in clothing. Garments were either decorated with feathers or made with thread spun from cotton and feather pieces. The clothes of eagle warriors were completely covered in feathers. Fabric made with feather thread was favored by noble men and women, showing their high status. Today, the only remaining example of this practice is the making of wedding huipils in Zinacantán, Chiapas. These modern huipils use feathers added to store-bought cotton thread.

Featherwork Meets Europe

When the Spanish arrived in Mexico, they were very impressed by the local birds and the feather art. Hernán Cortés received feather gifts from Moctezuma. As early as 1519, Cortés sent feathered shields, head decorations, and fans to Spain. In 1524, Diego de Soto brought feather artwork, including shields with scenes of sacrifice, to King Charles V. In 1527, Cortés sent 38 featherwork pieces to Asia.

After the Spanish Conquest, feather art continued, but on a smaller scale. Its uses changed. The use of featherwork in pagan rituals stopped with the spread of Christianity. However, some surviving works show Christian religious themes. Featherwork was still used in war. Feather mosaics remained popular, with many sent to Europe, Guatemala, and Peru. Exotic feathers themselves were sent to Europe to decorate hats, horses, and clothing.

Many Spanish writers, like Hernán Cortés and Bernardino de Sahagún, wrote about how important featherwork was and how much it impressed them. Feathers added colors and light that were hard to create with paints, even though oil painting was advanced at the time. Mexican featherwork was highly valued. Even though feather art was also made in Asia, it was not as prized in the 1500s and 1600s as that from Mexico.

Christian Featherwork Art

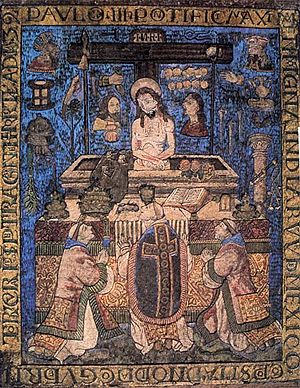

Featherwork and the Spanish Conquest led to a creative exchange from the 1500s to about 1800. Christian teachings added new themes to featherwork, including the making of religious items. Amantecas started creating Christian religious images just months after the Spanish arrived. These were sent to Europe and Asia. The first known Christian feather pictures were made for banners on cotton cloth. The Huejotzingo Codex shows the making of a feather and gold banner, which is the first sign of Christian featherwork.

At first, the Spanish tried to stop featherwork to get rid of the old religion. But they soon changed their minds and hired feather workers to create Christian images. These new works are called "feather mosaics" because they used small feather pieces. Most were in the Baroque style, as artists copied images from Spain. After the Conquest, hummingbird feathers were used to decorate images of Christ in Michoacán. Native craftsmen made crosses and candlesticks decorated with green feathers called quezalli. Small feather images and pendants were also made as protective charms.

The feather mosaics of the 1500s used different sized feathers combined with paper strips. Over the years, the feathers became smaller, the designs more balanced, and more subtle. Gold leaf and colored brushwork were added. The main images were European, but the edges sometimes showed old native designs. Feather art focused on saints and figures related to religious groups. These always followed the rules of the Council of Trent. Feathered religious items were sent to Europe, including to several popes in Rome. Many of these were given as gifts to other nobles and can now be found in museums across Europe. Featherwork became popular among kings, nobles, and scholars from the 1500s to 1700s. Some pieces even reached China, Japan, and Mozambique.

Besides images, feathers were used to decorate priests' clothes like chasubles and miters. They also made feather decorations for church altars. Feathered miters were sent to European bishops, especially in southern Europe, and were used during Mass. These feathered vestments appeared after the mid-1500s. European pictures were used as models for feather images on miters. However, these Christian images were not exact copies. Elements from several pictures were combined, and even old native designs appeared in some.

Monastery schools in Mexico, especially those run by the Franciscans, taught featherwork, especially feather mosaics. The skills of these artists remained important, even allowing them to copy Latin writing. One famous example is "Sacras de Ambras" at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. A notable area for colonial feather working was Patzcauaro, Michoacán. These workers kept many of the old privileges from before the Spanish arrived.

Mesoamerican featherwork inspired European artists. For example, Dionisio Minaggio, a gardener in Milan, learned the technique and created feather pictures of birds from his region. Other artists like Tommaso Ghisi also used the technique for collections of important families.

Featherwork: 1600s to 1900s

The best time for Mexican featherwork ended in the early 1600s. It declined because the old masters died. Demand for the work also went down because the Spanish started to look down on native crafts. Oil painting became more popular for religious images.

In the 1600s, featherwork images became more varied. They included the Virgin of Guadalupe and figures from European mythology, especially on fans for ladies. Techniques changed, with more paper strips used in mosaics instead of gold trim. One image of the Virgin of Guadalupe is made entirely of feathers. Another important 17th-century piece shows the Assumption of Mary, now in the Museum of the Americas in Madrid.

More changes happened in the 1700s, perhaps because non-native people also started doing featherwork. Oil paint was used along with feathers to show people's faces and hands, landscapes, and animals. Tiny paper strips were no longer used.

By the 1800s, the craft almost disappeared. Only a little activity remained in Michoacán. Many works were made with cheap, dyed feathers and had little artistic value. However, they still caught the attention of visitors to Mexico. In 1803, Alexander von Humboldt visited Pátzcuaro and saw a feather image of Our Lady of Health. Her hands and face were painted with oil, but the rest was made of hummingbird feathers.

The nuns at the Santa Rosa Convent in Puebla were known for their featherwork in the 1800s. Several of their works still exist. In the mid-1800s, lithography (a printing method) came to Mexico. Some prints were used as bases for featherwork, which were then backed with metal sheets. In Puebla, this was popular for folk figures like the China Poblana. The last new idea in the craft was using photographs. One such work used a photograph of Juan Arriaga de Yturbe, made in 1895.

Featherwork: 1900s to 2000s

By the 1900s, featherwork was mostly a handcraft, not a fine art. One reason was that many bird species disappeared, leading to a lack of fine feathers. In the first half of the century, featherwork images were almost always on postcards or informal items. They showed things like cockfights or birds made with dyed chicken or turkey feathers. Manuel Gamio tried to bring back featherwork as an art form. In 1920, he designed two large feather murals, one with an Aztec serpent and one with a Mayan serpent. They were made on black silk with quetzal feathers, gold, silver, and silk threads. However, we don't know what happened to these works.

Similarly, clothes made with feathers have almost completely disappeared. The only remaining example is the wedding huipil made by the Tzotzils in Zinacatlan, Chiapas. However, these have feathers added to store-bought cotton thread as decoration. Thread spun with feathers is no longer made. Another notable piece was a copy of the "Montezuma headdress" made for the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

In the late 1900s, some artists tried to revive the technique as an art form. Carmen Padin researched the technique and exhibited her work, which included robes, capes, and shields. But she had to stop in the 1990s because it was hard to get feathers. Josefina Ortega Salcedo also studied featherwork and created portraits copied from photographs. However, she no longer works with this technique either. Those who still continue include Elena Sanchez Garrido, who mixes featherwork and watercolors, and Tita Bilbaro, who makes Aztec and modern images using feathers, sand, fabric, and shells.

One notable family that continues the technique as a handcraft is the Olay family. This tradition started when Gabriel Olay learned the basics of feather working from an indigenous person. He passed his craft to his children and grandchildren. Most of the family makes copies of ancient images. Gabriel Olay Olay has created many works and lives in Tlalpujahua, Michoacan. Four of his pieces are in the Morelia Cultural Center, and others are in museums in Michoacán. His image of the Virgin of Guadalupe was given by a Mexican president to Pope John XXIII and is now in the Vatican's collection. Grandson Hans Matias Olay specializes in copying the birds and flowers that the Nahuas in Guerrero paint on amate paper. The Olays try to keep the ancient techniques alive, avoiding peacock and pheasant feathers because they are not native to Mexico. They use Campeche wax to attach the feathers and amate paper as the backing.

Other feather artists include Juan Carlos Ortiz of Puebla, who also creates feather mosaics, and Jorge Castillo of Taxco, who combines silver and feathers.

The most common use of feathers in modern Mexico is in traditional dance costumes. These include headdresses for dances like the Quetzales in Puebla and the Concheros in central Mexico. In Oaxaca, there is the Dance of the Feather, which uses dyed ostrich feathers. For the Dance of Calala in Suchiapa, Chiapas, the main dancer uses a fan of turkey and rooster feathers. Ostrich feathers are most common in dance costumes, followed by rooster, turkey, and hen feathers. Peacock feathers are rarely used. In most cases, the original meaning of the feathers has been forgotten. A special exception is the Huichols, who have kept much of their traditional beliefs.

Famous Featherwork Pieces

Even though featherwork was popular from ancient times into the early colonial period, few pieces survive today. One reason is that these pieces need special care. It's important to know about each type of feather to use and preserve them correctly. The best feathers to use are those that have fallen off naturally, as they last longer. A feather object can last a very long time if kept in a sealed case with controlled humidity, darkness, and low temperature. However, this makes it hard to see the piece. These objects can be shown in galleries and museums with little damage if temperature and humidity are controlled and light is kept low.

Perhaps the most famous piece is the so-called Montezuma's headdress. Despite its name, studies show it was probably not worn by the Aztec emperor. It was most likely made for a statue, as it looks like the one for Quetzalcoatl shown in the Codex Magliabechiano. The original is in the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna. A copy made with traditional techniques is in the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Many beautiful feather mosaics were sent to Europe, so several important pieces are in museums and collections there. The oldest feather piece made by Christian native workers is the Misa de San Gregorio at the Museum of the Jacobins in Auch, France. It was ordered by Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin, a relative of Moctezuma who became Christian, and Pedro de Gante. It was probably made by artisans from San Jose de Belen de los Naturales. It is dated 1539 and was meant as a gift for Pope Paul III. It was found again in 1987. Another notable work from the 1800s is San Lucas pintando a la Virgen, in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. The clothing is made of feathers, but the face and hands are painted with oil.

However, many important feather mosaic pieces remain in Mexico. San Pedro is a 16th-century work found at the archbishopric of Puebla. Another piece in Puebla is a portrait of Juan de Palafox y Mendoza. La Piedad is from the 1600s at the Franz Mayer Museum. It shows Mary holding Jesus after his death. Another piece in this museum is the Virgen del Rosario, also from the 1600s. An important 16th-century image is Salvator Mundi at the Museum of Tepotzotlan. It shows influences from Byzantine art.

No examples of feather fabric from before the Conquest survive. Only a few exist from the colonial period. Important cloths of this type include two mantles from San Miguel Zinacantepec, the Huipil of La Malinche at the Museum of Anthropology, and the Paño Novohispano at the Museo Textil de Oaxaca. All have feathers or feather pieces either sewn onto or twisted into cotton.

Church clothes, especially miters, can be found in various collections in Europe, including the Vatican. The church of Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome, has two sets of 18th-century vestments that were gifts from Mexico. These include two miters with a base of flax paper and silk, with white feathers glued onto it. On this background, small pieces of paper are sewn on, and then colored feathers are glued to these to form flower patterns.

See also

In Spanish: Plumaria de México para niños

In Spanish: Plumaria de México para niños