Moses Harris (mountain man) facts for kids

Moses Harris, also known as Black Harris, was a brave trapper, scout, and guide. He was a true "mountain man" who explored vast areas of North America. He traveled across the Continental Divide and all the way to the Pacific Ocean. He journeyed through the Rocky and Cascade Mountains. Harris also helped many pioneers who were traveling west. He even spoke the Shoshoni language. He passed away on May 6, 1849.

Contents

Early Life of Moses Harris

Moses Harris was thought to have come from either South Carolina or Kentucky. Some people believe he might have been partly African American. He was described as a "free black mountain man." He had dark skin and hair, with brown eyes, and was of medium height.

Becoming a Trapper and Explorer

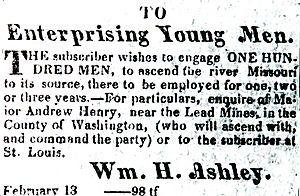

Moses Harris might have started trapping for William H. Ashley around 1822. By 1823, he was already seen as an experienced mountaineer. He knew a lot about the customs of Native American tribes. In 1841, he wrote a letter saying he had been well-known in the mountains for 20 years. This shows how long he had been exploring.

Journey Across the Great Divide

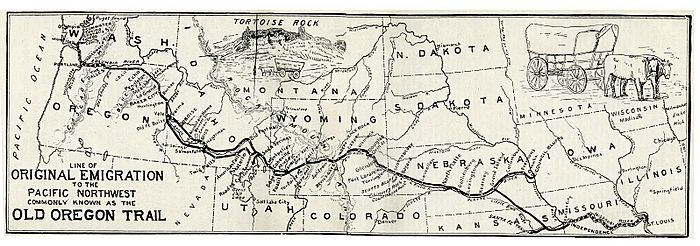

In 1824, Harris joined a group of 26 men. They were led by General William H. Ashley. They started from Fort Atkinson on the Missouri. Their goal was to cross the Continental Divide and reach the Green River. They planned to follow the Platte River, North Platte River, Sweetwater, and South Pass.

The group included famous explorers like James Beckwourth and Thomas Fitzpatrick. They were warned to take a different route, and Ashley changed their path. The journey began with a big blizzard. Many of their 50 pack horses died. Later, a group of Crow people stole some of their horses.

This journey was very important. It helped map out the first part of the central overland route to the Pacific Ocean. Ashley was the first white person to travel this route in winter. He was also the first American to explore the mountains of Northern Colorado.

Moses Harris: Trapper and Guide

In the winter of 1825-1826, William Sublette chose Harris to travel with him to St. Louis. They used pack dogs and wore snowshoes to get through the snow. The next spring, these two men guided Ashley through the South Pass.

Harris became an expert in winter travel. He spent many years trapping furs in the mountains. He also lived in Missouri during the 1830s. Besides trapping, he guided groups of trappers on their journeys.

A Free Trapper's Life

By 1832, Harris was a free trapper. This meant he did not work for a big fur trading company. He was among 150 trappers at the fur-trade rendezvous at Pierre's Hole in July 1832. This was a big meeting where trappers traded furs and supplies.

The next spring, Harris and other trappers were attacked by Arikara Native Americans. Their horses were taken, but they managed to keep their beaver furs. Harris walked to the rendezvous that year. In 1833, he traveled back to St. Louis with Dr. Benjamin Harrison.

Harris is also believed to have helped build Fort Laramie between 1834 and 1835.

Guiding Missionaries and Explorers

In 1836, Harris guided Narcissa and Marcus Whitman for part of their trip to Oregon. Narcissa Prentiss Whitman wrote in her diary that she had tea with Harris on June 4, 1836. They traveled together to the Green River fur-trade rendezvous.

In 1837, artist Alfred Jacob Miller made sketches during his trip through the Green River Valley. He went to the yearly fur-trader's rendezvous in western Wyoming. About 120 trappers were there. The path Miller took later became part of the Oregon Trail. Miller later created 200 watercolors from his sketches.

In 1838, a fur company hired Harris to guide a group. This group included missionary couples and Johann August Sutter. They traveled from Missouri to the rendezvous at the Green River. The missionaries were heading to Oregon.

Harris also traveled with trappers and missionaries to the rendezvous in 1839. He guided the missionaries for part of their journey to Oregon.

Leading Wagon Trains West

Moses Harris often led pioneers traveling west. He guided them from Fort Hall in Idaho to northern Nevada, California, and Oregon. He helped find better routes across the Cascade Mountains. Fort Hall was first built by American fur traders. By 1841, it was sold to the North West Fur Company.

Harris was worried that the British wanted to keep Americans out of Oregon Country. He believed they were encouraging Native Americans to attack Americans. He also said they controlled the sale of many furs from American land. Harris offered to help remove the British and Native Americans from Oregon.

The New Orleans Picayune newspaper published stories about Harris's mountain travels. In 1844, the paper announced his upcoming trip from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon. This trip was expected to take four months.

Guiding the 1844 Pioneer Group

In 1844, Harris guided a large group of 500 pioneers. This group included George Washington Bush. They were moving west to settle in the Willamette Valley in what is now Oregon. The journey was very difficult. It was an unusually rainy spring, causing floods and muddy trails. This slowed the wagon train down a lot. In two months, they had only traveled 100 miles. Many people got sick with dysentery and rheumatism.

Finding New Routes and Rescuing Travelers

In 1845, Harris was part of a group trying to find a way for covered wagons to cross the Cascade Mountains. They started near the old mission in Salem, Oregon. They did not succeed at first. They tried two more times in 1846. Finally, a southern route was found. It was called the Applegate Trail and was better than the Barlow Road.

In 1845 and 1846, Harris led rescue parties. These groups saved people in wagon trains who were lost, starving, or sick. They also helped those who had been attacked by Native Americans. Among those saved were Hugh Linza McNary and Tabitha Moffatt Brown. When a wagon train led by Stephen Meek got lost, Harris traded for supplies with local Native Americans. He then led the survivors to The Dalles. He also helped rescue a group stuck in southern Oregon on the Applegate Trail.

Harris was famous for his stories. Some were real experiences, and some were tall tales. He was known as a "brave and useful man."

Later Years and Passing

Moses Harris returned to the United States from Oregon Country in 1846. He died from cholera in Independence, Missouri, on May 6, 1849. Cholera was a serious illness that affected Missouri many times between 1833 and 1873. The worst outbreaks happened in 1849.

His friend, James Clyman, wrote a poem for him in 1844:

-

-

- Here lies the bones of old Black Harris

- who often traveled beyond the far west

- and for the freedom of Equal rights

- he crossed the snowy mountain heights.

- He was a free and easy kind of soul

- especially with a Belly full.

-