American pika facts for kids

Quick facts for kids American pika |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| An American Pika feeding on grass in the Canadian Rocky Mountains | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Ochotona

|

| Species: |

princeps

|

| Subspecies | |

|

O. princeps princeps |

|

|

|

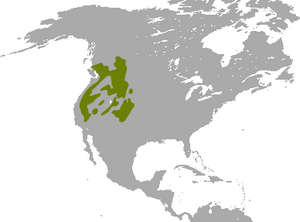

| American pika range | |

The American pika (Ochotona princeps) is a small, furry animal that lives in the mountains of western North America. It's active during the day and looks a bit like a tiny rabbit or hare, but it's actually a different kind of animal called a pika. You'll usually find them in rocky areas, like boulder fields, high up in the mountains where trees don't grow. They are herbivores, meaning they only eat plants.

Contents

Discover the American Pika

American pikas were once called "little Chief hares." They have a small, round body. They are about 16 to 22 centimeters (6 to 8.5 inches) long. They usually weigh around 170 grams (6 ounces), which is about as much as a baseball. Their size can be a bit different depending on where they live. Sometimes, males are a little bigger than females.

What Does a Pika Look Like?

Pikas are a medium-sized type of pika. Their back legs don't look much longer than their front legs. Their feet are covered in thick fur, except for black pads on their toes. Their ears are quite big and round, with fur on both sides. They are usually dark with white edges.

A pika's tail is "buried" in its fur, so you can't see it easily. Its fur color is the same for both males and females. However, the color can change with the seasons and where the pika lives. In summer, their fur is usually grayish to cinnamon-brown. In winter, it becomes grayer and longer. Their soft underfur is usually slate gray. Their belly fur is whitish.

Like rabbits, male pikas are called bucks and females are called does.

Where Pikas Live and Their Homes

American pikas live in the mountains of western North America. You can find them from central British Columbia and Alberta in Canada all the way down to the US states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California, and New Mexico. There are 30 types of pikas in the world, but only two live in North America. The other one is the collared pika, which lives farther north.

Pika Habitats

Pikas like to live in rocky areas called talus fields. These are places with lots of broken rocks, often found in high mountain areas. They also live in piles of broken rock. Sometimes, they even make homes in places built by humans, like old mine piles or stacks of wood.

Pikas usually make their dens and nests under rocks that are about 0.2 to 1 meter (8 inches to 3 feet) wide. They often sit on bigger, more noticeable rocks. They prefer cool, damp spots on high peaks or near streams. Pikas don't like hot temperatures. In the northern parts of their range, they might live near sea level. But in the south, they are rarely found below 2,500 meters (8,200 feet) high. Pikas use the natural spaces in the rocks for their homes. They don't dig burrows, but they can make their homes bigger by digging a little.

What Pikas Eat

The American pika is a generalist herbivore, meaning it eats many different kinds of plants. They enjoy various grasses, sedges, thistles, and fireweed. Even though they get water from the plants they eat, they will drink water if it's available.

How Pikas Find Food

Pikas have two main ways of getting food. They either eat plants right away, or they collect and store food in "haypiles" for winter. They eat plants all year round, but they only make haypiles in the summer. Pikas don't hibernate, so they need a lot of energy to stay active all winter.

When making haypiles, pikas are very busy! They can make over 100 trips a day to gather plants. The timing of when they start collecting hay depends on how much snow fell the previous winter. If there was little snow and an early spring, pikas start and finish haying earlier.

Pikas seem to pick plants that are the most nutritious. They choose plants with more calories, protein, fat, and water. They tend to store tall grasses and other leafy plants more often than eating them right away. Haypiles are usually stored under the rocks, close to where the rocky area meets the grassy meadow. Males usually store more plants than females, and adult pikas store more than young ones.

Pikas also produce two types of droppings. One type is hard, brown, and round. The other type is soft, black, and shiny. These soft pellets have more energy than stored plants, and pikas might eat them directly or store them for later.

Pika Life and Family

American pikas are active during the day. Each pika has a "home range," which is the area of land it uses. About 55% of this area is a "territory" that the pika defends from other pikas. The size of a territory can vary, depending on how much good vegetation is nearby.

The home ranges of pikas can overlap. Mating pairs (a male and female) have home ranges that are closer to each other than to other pikas of the same sex. Pikas protect their territories by being aggressive. However, actual fights are rare. They usually happen between pikas of the same sex who don't know each other. A pika might go into another's territory, but usually only when the owner isn't active. When pikas are collecting hay, they become even more protective of their territories.

Pika Families

Adult male and female pikas with nearby territories often form mated pairs. Females choose their mates if there is more than one male available. Female pikas can have two litters of babies each year, with about three young in each litter. Breeding happens about a month before the snow melts. The babies grow inside the mother for about 30 days.

Babies are born as early as March in lower areas, but from April to June in higher places. When born, pikas are quite helpless. They are blind, have a little bit of hair, and their teeth have just come in. They weigh about 10 to 12 grams (less than half an ounce) at birth. Around nine days old, they can open their eyes. Mothers spend most of the day looking for food and return to the nest every two hours to feed their young. Young pikas become independent after about four weeks, which is when they stop drinking their mother's milk. Young pikas might stay in their birth area or move to a nearby one. If they stay, they try to find areas away from their relatives. Young pikas often move away because they need to find their own territory.

Pika Communication and Predators

Pikas are very vocal. They use different calls and songs to talk to each other. A call is used to warn others if a predator is nearby. A song is used during the breeding season (only by males) and in the autumn (by both males and females). Animals that hunt pikas include eagles, hawks, coyotes, bobcats, foxes, and weasels.

Pika's Place in Science

The American pika was first described by a scientist named John Richardson in a book called Fauna Boreali-Americana in 1828. Its first scientific name was Lepus (Lagomys) princeps.

Pikas and Climate Change

Pikas live in cool mountain regions, so they are very sensitive to high temperatures. This makes them a good "early warning system" for detecting global warming in the western United States. Scientists think that rising temperatures are causing American pikas to move higher up the mountains to find cooler places to live.

However, pikas can't easily move to new areas because their homes are often small, disconnected "islands" of habitat in different mountain ranges. Pikas can die in just six hours if they are exposed to temperatures above 25.5°C (78°F) and can't find a cool place to hide. In warmer areas, like during the midday sun or at lower elevations, pikas usually become inactive and hide in cooler rock openings. Even so, pikas have managed to survive in hot places like Craters of the Moon and Lava Beds National Monuments in Idaho and California. In August, the average high temperatures there can be 32°C (90°F), and sometimes even reach 38°C (100°F).

Recent studies show that some pika populations are shrinking because of different reasons, especially global warming. A study from 2003 found that nine out of 25 pika populations in the Great Basin had disappeared. This led scientists to investigate further to see if the species as a whole is in danger.

In 2010, the US government thought about adding the American pika to the US Endangered Species Act, but decided not to. On the IUCN Red List, which tracks the conservation status of species, the American pika is still listed as a species of least concern. This means it's not currently considered to be at high risk of extinction.

The Pikas in Peril Project, which was funded by the National Park Service, started collecting information in May 2010. A large team of scientists and park staff worked together to understand how vulnerable the American pika is to future climate change in the western United States. This project finished in 2016.

- View the Pika genome in Ensembl.

- View the ochPri3 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.

See also

In Spanish: Pica americana para niños

In Spanish: Pica americana para niños