Sugar glider facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sugar glider |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Illustration by Neville Cayley | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Petaurus

|

| Species: |

breviceps

|

|

|

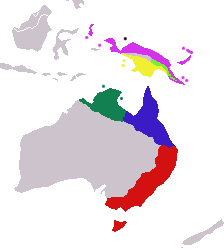

| (Former) Sugar glider range by subspecies: , now thought to be inaccurate

P. b. breviceps (introduced in Tasmania) P. b. tafa |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

P. (Belideus) breviceps, Waterhouse 1839 |

|

The sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps) is a small marsupial animal that lives in trees. It eats both plants and insects (omnivorous) and is active at night (nocturnal). It's also known for its amazing ability to glide through the air, like a flying possum. Its name comes from its love for sweet foods like sap and nectar, and its gliding skill. Even though they look and act like flying squirrels, they are not closely related. This is an example of convergent evolution, where different animals develop similar traits. The scientific name, Petaurus breviceps, means "short-headed rope-dancer" in Latin, which describes how they move skillfully through tree branches.

Sugar gliders have special gliding membranes called patagia. These membranes stretch from their front legs to their back legs. Gliding helps them reach food and escape from predators easily. Their fur is soft and ranges from pale grey to light brown. It's lighter on their belly, which helps them blend in (this is called countershading).

The sugar glider lives in a small part of southeastern Australia. You can find them in southern Queensland and most of New South Wales, east of the Great Dividing Range. Some animals called "sugar gliders" that are kept as pets might actually be a different species from West Papua, called Krefft's glider (P. notatus).

Contents

Understanding Sugar Glider Species

For a long time, scientists thought the sugar glider was one species found across Australia and New Guinea. They believed there were seven different types (subspecies) based on small differences in their looks, like color and size. However, new studies using mitochondrial DNA (genetic material) showed that these types might not be truly separate groups.

More recent research found big differences within the sugar glider populations. These differences were so large that scientists decided to split them into several species. For example, the type from Biak Island was reclassified as its own species, the Biak glider (Petaurus biacensis).

In 2020, a major study showed that what we called P. breviceps was actually three different "hidden" species. These are the Krefft's glider (Petaurus notatus), found in most of eastern Australia and introduced to Tasmania; the savanna glider (Petaurus ariel), found in northern Australia; and the true P. breviceps, which lives only in a small area of coastal forest in southern Queensland and most of New South Wales. This means the true sugar glider has a much smaller home range than once thought. This makes them more sensitive to dangers like the 2019-20 Australian bushfires, which badly damaged their homes.

Scientists believe the true sugar glider and Krefft's glider became separate species because they were geographically isolated. This happened after Australia became drier following the Pliocene period and the Great Dividing Range mountains rose. This process is called allopatric speciation.

Where Sugar Gliders Live

Sugar gliders live in the coastal forests of southeastern Queensland and most of New South Wales. They can be found at high altitudes, up to 2000 meters, in the eastern mountain ranges. In some areas, their habitat might overlap with the Krefft's glider (P. notatus).

Sugar gliders can live in the same areas as squirrel gliders and yellow-bellied gliders. They manage to coexist by using different resources, meaning each species has its own way of finding food and shelter.

Like other animals that live in trees and are active at night, sugar gliders are busy after dark. During the day, they rest in tree hollows that they line with leafy twigs.

A sugar glider's average home range is about 0.5 hectares (about 1.2 acres). The size of their home depends on how much food is available. There are usually two to six sugar gliders per hectare (0.8–2.4 per acre).

Their main predators are native owls (Ninox species). Other animals that hunt them include kookaburras, goannas, snakes, and quolls. Feral cats are also a big threat to them.

Appearance and Body Features

The sugar glider has a body similar to a squirrel, with a long tail that can weakly grasp things. From its nose to the tip of its tail, it measures about 24 to 30 centimeters (9.4 to 11.8 inches). Males usually weigh around 140 grams (4.9 ounces), and females weigh about 115 grams (4.1 ounces). Their heart beats 200–300 times per minute, and they breathe 16–40 times per minute.

Male sugar gliders are typically larger than females. This difference in size between males and females (called Sexual dimorphism) likely developed because males compete more for mates in social groups. This size difference is even more noticeable in colder regions where there's more food, leading to more competition.

Sugar gliders have thick, soft fur that is usually blue-grey. Some can be yellow, tan, or, very rarely, albino (all white). A black stripe runs from their nose to the middle of their back. Their belly, throat, and chest are cream-colored.

Males have four scent glands: one on their forehead, one on their chest, and two near their cloaca (a body opening). They use these glands to mark other group members and their territory. The scent glands on a male's head and chest look like bald spots. Females also have a scent gland near their cloaca and one inside their pouch, but they don't have glands on their chest or forehead.

Since sugar gliders are nocturnal, their large eyes help them see well at night. Their ears can swivel, helping them find prey in the dark. Their eyes are set far apart, which allows them to judge distances more accurately when gliding from one spot to another.

Each of a sugar glider's feet has five toes. Their back feet have an opposable toe (like a human thumb) that doesn't have a claw. This toe can bend to touch all the other toes, helping them grip branches tightly. The second and third toes on their back feet are partly joined together (this is called syndactylous), forming a comb they use for grooming. The fourth toe on their front foot is sharp and long, which helps them pull insects out from under tree bark.

The gliding membrane stretches from the fifth toe of each front foot to the first toe of each back foot. When they stretch out their legs, this membrane allows them to glide long distances. Strong muscles control the membrane's movement, along with their body and tail.

In the wild, sugar gliders can live up to 9 years. In captivity, they typically live up to 12 years, with the longest reported lifespan being 17.8 years.

Biology and Behavior

How Sugar Gliders Glide

The sugar glider is one of several gliding possums in Australia. When it glides, it stretches its front and back legs out at right angles to its body, with its feet pointed upwards. The animal launches itself from a tree, spreading its limbs to open up its gliding membranes. This creates an aerofoil (a shape that helps it fly) that allows it to glide 50 meters (55 yards) or more. For every 1.82 meters (6 feet) it travels forward, it drops about 1 meter (3.3 feet). They steer by moving their limbs and changing how tight their gliding membrane is. For example, to turn left, they lower their left forearm.

This way of moving through trees is mostly used to travel from one tree to another. Sugar gliders rarely go down to the ground. Gliding helps them avoid predators in the trees and keeps them from touching predators on the ground. It might also save them time and energy when looking for food that is spread out. Young joeys in the mother's pouch are protected from landing forces by a special wall (septum) inside the pouch.

Torpor: Saving Energy

Sugar gliders can handle hot temperatures up to 40°C (104°F) by licking their fur and drinking small amounts of water.

In cold weather, sugar gliders huddle together to stay warm. They can also enter a state called torpor to save energy. Torpor is like a short, daily nap where their body temperature drops. It's different from hibernation, which is a longer, deeper sleep. Before going into torpor, a sugar glider will reduce its activity and body temperature to save energy. When food is scarce, especially in winter, they lower their body temperature to between 10.4°C (50.7°F) and 19.6°C (67.3°F). This helps them save energy. To survive the cold season, sugar gliders need to gain a lot of fat in the autumn (May/June). Wild sugar gliders go into torpor more often than those in captivity. They use torpor most frequently in winter when it's cold, rainy, and food is harder to find.

What Sugar Gliders Eat

Sugar gliders are omnivores, meaning they eat a wide variety of foods depending on the season. They mostly look for food in the lower parts of the forest canopy. They can get up to half of their daily water from rainwater, with the rest coming from the water in their food.

In summer, they mainly eat insects. In winter, when insects are hard to find, they mostly eat plant liquids like acacia gum, eucalyptus sap, manna, honeydew, or lerp. Sugar gliders have a large caecum (a part of their digestive system) that helps them digest the complex sugars from gum and sap.

To get sap or gum, sugar gliders will strip bark off trees or make holes with their teeth to reach the liquid inside. They don't spend much time hunting for insects because it uses a lot of energy. Instead, they wait for insects to fly into their area or stop to feed on flowers.

Gliders eat about 11 grams (0.39 ounces) of dry food per day. This is roughly 8% of a male's body weight and 9.5% of a female's body weight.

They are opportunistic feeders, meaning they eat whatever is available. They can also be carnivorous, preying on small lizards and birds. They eat many other foods when they can find them, such as nectar, acacia seeds, bird eggs, pollen, fungi, and native fruits. Pollen can be a big part of their diet, so sugar gliders are likely important pollinators for Banksia plants.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Like most marsupials, female sugar gliders have two ovaries and two uteri. They can go into heat (be ready to mate) several times a year. The female has a marsupium (pouch) in the middle of her belly where she carries her babies. The pouch opens towards the front, and it has two side pockets that get bigger when babies are inside.

Males become ready to breed between 4 and 12 months old, while females are ready between 8 and 12 months. In the wild, sugar gliders usually have one or two litters a year, depending on the weather and habitat. In captivity, they can breed more often because they have stable living conditions and good food.

A female sugar glider usually gives birth to one (19% of the time) or two (81% of the time) babies, called joeys. The pregnancy lasts 15 to 17 days. After birth, the tiny joey, weighing only 0.2 grams (0.007 ounces), crawls into its mother's pouch to continue developing. They are born very undeveloped and without fur, with only their sense of smell working. The mother has a scent gland in her pouch to attract the blind joeys from the uterus. Joeys have a temporary cartilage arch in their shoulder that helps them climb into the pouch.

Young joeys stay completely inside the pouch for 60 days after birth. There, they drink milk from their mother's mammae (milk glands) to grow. Their eyes open around 80 days after birth, and they leave the nest around 110 days after birth. By the time they are weaned (stop drinking milk), their body temperature control system is developed. With their larger size and thicker fur, they can regulate their own body temperature.

In southeastern Australia, breeding happens seasonally, with babies born only in winter and spring (June to November). Unlike animals that move on the ground, sugar gliders and other gliding species have fewer, but heavier, babies per litter. This allows the female sugar glider to still be able to glide when she is pregnant.

Social Life of Sugar Gliders

Sugar gliders are very social animals. They live in family groups or colonies with up to seven adults, plus the young born that season. A group can have up to four different age groups, though some sugar gliders live alone. They engage in social grooming, which not only keeps them clean and healthy but also helps the colony bond and feel like a group.

In a social group, there are usually two main males who are in charge and keep other males in line. These two main males are often related and don't fight each other. They share food, nests, mates, and the job of marking group members and their territory with scent.

The territory and group members are marked with saliva and a special scent from glands on the forehead and chest of male gliders. Any intruders who don't have the right scent mark are aggressively chased away. Rank within the group is shown through scent marking, and fighting usually doesn't happen within the group itself, only when different groups meet. Each colony protects a territory of about 1 hectare (2.5 acres) where eucalyptus trees provide their main food.

Sugar gliders are one of the few mammals where the male helps care for the babies (this is called male parental care). The oldest main male in a group often takes great care of the young, as he is likely the father. This male parental care developed because young sugar gliders are more likely to survive when both parents help. Both parents can take turns huddling with the young to prevent them from getting too cold (hypothermia) while the other parent goes out to find food. Young sugar gliders can't control their own body temperature until they are about 100 days old (3.5 months).

Sugar gliders communicate using sounds, visual signals, and complex chemical smells. Smells are very important for communication, especially for nocturnal animals like sugar gliders. They use smells to mark their territory, show their health, and indicate their rank within the group. Gliders also make various sounds, including barking and hissing.

Sugar Gliders and Humans

Protecting Sugar Gliders

Based on older ways of classifying them, the sugar glider was not considered endangered. Its conservation status was "Least Concern (LC)" on the IUCN Red List. However, newer studies show that the true sugar glider lives in a small, specific area. This means it is much more sensitive to threats. For example, its native home was severely affected by the 2019-20 Australian bushfires, which happened just before the new studies were published. Sugar gliders rely on tree hollows for shelter, making them very vulnerable to intense fires.

Despite losing some natural habitat in Australia over the last 200 years, the sugar glider can adapt. It can live in small patches of remaining bushland, especially if it doesn't have to cross large open areas to reach them. Sugar gliders can survive in areas that have been mildly logged, as long as three to five trees with hollows are left per hectare. While they are not currently threatened by habitat loss, their ability to find food and avoid predators might be reduced in areas with a lot of light pollution.

In Australia, laws protect sugar gliders as a native species at federal, state, and local levels. The main conservation law in Australia is the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). For example, in South Australia, under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974, you can legally keep only one sugar glider without a permit, as long as you got it legally from someone with a permit. You need a permit to have more than one glider, or if you want to sell or give away any glider. It is against the law to catch or sell wild sugar gliders without a permit.

Sugar Gliders in Captivity

When sugar gliders are kept as pets, they can suffer from calcium deficiencies if they don't get the right food. A lack of calcium makes their body take calcium from their bones, and their back legs are usually the first to show problems. To prevent this, the ratio of calcium to phosphorus in their diet should be 2:1. This problem is sometimes called hind leg paralysis (HLP). Their diet should be 50% insects (that have been fed nutritious food, called gut-loaded) or other protein sources, 25% fruit, and 25% vegetables. Some well-known diets include Bourbon's Modified Leadbeaters (BML), High Protein Wombaroo (HPW), and various calcium-rich diets with Leadbeaters Mixture (LBM). Another diet problem reported in captive gliders is iron storage disease (hemochromatosis), which can be deadly if not found and treated early.

Sugar gliders are very social, so they need a lot of attention and environmental enrichment, especially if they are kept alone. Not enough social interaction can lead to sadness and behavioral problems like losing their appetite, being irritable, and even hurting themselves.

As a Pet

In many countries, the sugar glider (or what was once thought to be the sugar glider) is a popular exotic pet, sometimes called a pocket pet. In Australia, some groups, like Australia's largest wildlife rehabilitation organization (WIRES), are against keeping native animals as pets. Australian wildlife conservation organizations are also concerned about the welfare risks, including neglect, cruelty, and abandonment.

In Australia, sugar gliders can be kept as pets in Victoria, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. However, it is not allowed to keep them as pets in Western Australia, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland, or Tasmania.

DNA analysis suggests that the "sugar glider" population in the United States originally came from West Papua, Indonesia. This means they were not illegally taken from other native areas like Papua New Guinea or Australia. Since the gliders from West Papua have been tentatively classified as Krefft's gliders, it indicates that the captive gliders kept in the United States are likely Krefft's gliders, not the true sugar gliders.

See also

In Spanish: Petauro del azúcar para niños

In Spanish: Petauro del azúcar para niños