Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Naval Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||||

British ships seen following the German ships |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3 battlecruisers 4 armoured cruisers 4 light cruisers 14 destroyers |

1 battlecruiser 1 light cruiser |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| none | 4 sailors | ||||||

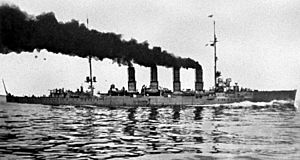

The pursuit of Goeben and Breslau was an exciting chase at sea that happened at the very start of World War I. Two powerful German warships, the battlecruiser SMS Goeben and the light cruiser SMS Breslau, were trying to escape from the British navy in the Mediterranean Sea.

The German ships managed to get away. They sailed through the Dardanelles strait and reached Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), the capital of the Ottoman Empire. There, they were given to the Ottoman navy. Renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim and Midilli, these ships were then used by their German commander to attack Russian ports. This action helped bring the Ottoman Empire into the war on the side of Germany and its allies.

Even though no big battle happened, this chase had huge effects on the war. It ended the careers of the two main British admirals involved. Winston Churchill, who was in charge of the British navy at the time, later said that by bringing Turkey into the war, the Goeben caused "more slaughter, more misery, and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship."

Contents

Setting the Scene for the Chase

In 1912, Germany sent a small group of ships called the Mittelmeerdivision (Mediterranean Division) to the Mediterranean Sea. This group included only the Goeben and Breslau, led by Admiral Wilhelm Souchon. Their job was to stop French ships carrying soldiers from Algeria to France if war broke out.

When war started between Austria-Hungary and Serbia on July 28, 1914, Admiral Souchon was in Pula, where the Goeben was being repaired. He didn't want his ships to get trapped in the Adriatic Sea. So, he quickly finished as many repairs as possible and sailed into the Mediterranean. He tried to get coal in Italy, but Italy decided to stay neutral and wouldn't help him. Souchon then met up with the Breslau and got some coal from German merchant ships in Messina.

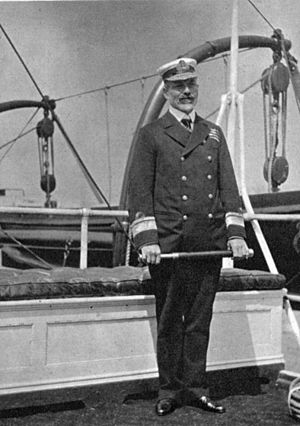

Meanwhile, on July 30, Winston Churchill, who was the head of the British navy, told Admiral Archibald Berkeley Milne, the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, to protect the French troop ships. Milne's fleet was based in Malta. It had three fast battlecruisers (HMS Inflexible, Indefatigable, and Indomitable), plus other cruisers and destroyers.

Milne's orders were to help the French and, if possible, attack any fast German ships, especially the Goeben. He was told not to fight stronger enemy forces alone. Churchill later said this meant avoiding the Austrian fleet, which had bigger battleships. Milne gathered his ships at Malta on August 1. On August 2, he was told to follow the Goeben with two battlecruisers and watch the Adriatic Sea for Austrian ships. The British light cruiser HMS Chatham was sent to search for Goeben near Messina. However, Souchon had already left Messina on the morning of August 3, heading west.

First Sightings

Without clear orders, Admiral Souchon decided to go to the coast of French Algeria. He planned to attack French troop ships and bombard the ports of Bône and Philippeville. The Goeben headed for Philippeville, and the Breslau went to Bône. On August 3, he learned that Germany had declared war on France. Then, early on August 4, Souchon received new orders: "Proceed at once to Constantinople."

But Souchon was so close to his targets that he ignored the new order for a moment. He flew the Russian flag to avoid being seen and attacked the French ports at dawn. After the attack, he turned back towards Messina to get more coal.

At 9:30 AM on August 4, Souchon's ships met the two British battlecruisers, Indomitable and Indefatigable. They passed each other going in opposite directions. Neither side fired because Britain had not yet declared war on Germany. The British ships started following the Germans, but the German ships were faster and quickly pulled ahead. Milne reported seeing the German ships but didn't tell London that they were heading east. Churchill still thought they were going to attack French transports, so he allowed Milne to attack if the Germans fired first. However, the British government decided that fighting couldn't start before a war declaration. So, Churchill had to cancel his attack order.

The Chase Continues

The Goeben was supposed to be very fast, but her damaged boilers meant she could only go about 24 knots (44 km/h). This was achieved by pushing the crew and engines to their limits; four sailors died from hot steam. Luckily for Souchon, both British battlecruisers also had boiler problems and couldn't keep up. The British light cruiser HMS Dublin stayed in contact, but the bigger British ships fell behind. In fog and dim light, the Dublin lost sight of the German ships off Cape San Vito at 7:37 PM. The Goeben and Breslau returned to Messina the next morning, by which time Britain and Germany were officially at war.

The British navy told Milne to respect Italy's neutrality. This meant he had to stay outside a 6-mile (10 km) limit from the Italian coast, which stopped him from entering the Straits of Messina. So, Milne placed ships at the exits of the Straits. He still thought Souchon would head west towards the Atlantic. He put two battlecruisers, Inflexible and Indefatigable, to cover the northern exit. The southern exit was covered by only one light cruiser, HMS Gloucester.

Messina was not a safe place for Souchon. Italian officials insisted he leave within 24 hours and wouldn't give him coal. To get enough fuel, his crew had to tear up the decks of German merchant ships in the harbor and shovel coal by hand into the Goeben's bunkers. By the evening of August 6, he only had enough coal to reach Constantinople. He also received new messages saying Austria wouldn't help him and that the Ottoman Empire was still neutral, so he shouldn't go to Constantinople.

Souchon faced a choice: go to Pola and likely be trapped for the rest of the war, or head for Constantinople anyway. He chose Constantinople, hoping to "force the Ottoman Empire, even against their will, to spread the war to the Black Sea against their ancient enemy, Russia."

Milne was told on August 5 to keep watching the Adriatic for the Austrian fleet and stop the German ships from joining them. He kept his battlecruisers in the west. He sent the Dublin to join Admiral Ernest Troubridge's cruiser squadron in the Adriatic, believing they could stop Goeben and Breslau. Troubridge was told "not to get seriously engaged with superior forces." This was meant to warn him about the Austrian fleet.

When Goeben and Breslau came out into the eastern Mediterranean on August 6, they were met by the British light cruiser Gloucester. Since the Gloucester was outgunned (meaning its guns were smaller and less powerful), it just followed the German ships.

Troubridge's squadron had armored cruisers and destroyers. His ships had smaller guns and thinner armor compared to the Goeben. This meant his ships were not only outranged by Goeben's powerful guns, but their own guns probably couldn't seriously damage the German ship. Also, the British ships were slower than Goeben. Troubridge realized his only chance was to attack at dawn, with the sun behind his ships, and ideally launch torpedoes with his destroyers. However, many of his destroyers didn't have enough coal to keep up. By 4:00 AM on August 7, Troubridge knew he couldn't catch the German ships before daylight. Remembering the order not to fight a "superior force," he decided to stop the chase. He didn't get a reply from Milne until 10:00 AM, by which time he had already turned back to refuel.

The Escape

Milne ordered the Gloucester to stop following, still thinking Souchon would turn west. But the Gloucester's captain knew the Goeben was escaping. The Breslau tried to make the Gloucester break off, because Souchon had a coal ship waiting near Greece and needed to meet it. The Gloucester finally attacked the Breslau, hoping this would make the Goeben come back to protect it. According to Souchon, the Breslau was hit, but not badly damaged. The fight then stopped. Finally, Milne ordered the Gloucester to end its pursuit at Cape Matapan.

Just after midnight on August 8, Milne took his three battlecruisers and a light cruiser, HMS Weymouth, east. At 2:00 PM, he got a wrong message saying Britain was at war with Austria. This was corrected four hours later, but Milne chose to guard the Adriatic instead of looking for Goeben. Finally, on August 9, Milne got clear orders to "chase Goeben which had passed Cape Matapan on the 7th steering north-east." Milne still didn't believe Souchon was heading for the Dardanelles. So, he decided to guard the exit from the Aegean, not knowing that Goeben didn't plan to come out.

Souchon refueled his ships off the Greek island of Donoussa on August 9. The German warships then continued their journey to Constantinople. At 5:00 PM on August 10, they reached the Dardanelles and waited for permission to pass through. Germany had been working to gain influence with the Turkish government. Now, Germany used this influence to pressure the Turkish Minister of War, Enver Pasha, to let the ships pass. This act would make Russia very angry, as Russia depended on the Dardanelles for its main shipping route. The Germans also convinced Enver to order Turkish forces to fire on any British ships that tried to follow. By the time Souchon got permission to enter the straits, his lookouts could see smoke from approaching British ships on the horizon.

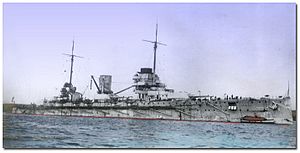

Turkey was still a neutral country and was supposed to stop German warships from passing through the straits. To get around this rule, it was agreed that the ships would become part of the Turkish navy. On August 16, after reaching Constantinople, Goeben and Breslau were officially given to the Turkish Navy in a small ceremony. They were renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim and Midilli, but they kept their German crews, and Souchon remained in command. At first, Britain was happy that a threat had been removed from the Mediterranean. On September 23, Souchon was made commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Navy.

What Happened Next

In August, Germany expected to win the war quickly and was fine with the Ottoman Empire staying neutral. Just having a powerful warship like Goeben in the Sea of Marmara was enough to keep a British naval group busy guarding the Dardanelles. However, after Germany faced setbacks in September, and Russia had successes against Austria-Hungary, Germany started to see the Ottoman Empire as a useful ally. Tensions grew when the Ottoman Empire closed the Dardanelles to all shipping on September 27. This blocked Russia's exit from the Black Sea, which was vital for over 90 percent of Russia's trade.

Germany's gift of the two modern warships had a huge positive impact on the Turkish people. At the start of the war, Churchill had angered Turkey by taking two almost finished Turkish battleships that were being built in British shipyards. These ships, Sultan Osman I and Reshadieh, had been paid for by public donations in Turkey. Turkey was offered money as compensation if it stayed neutral. (These ships were then used by the British navy as HMS Agincourt and HMS Erin.) Before this, the Turkish navy was generally friendly with Britain, while the army favored Germany. These events helped push the Ottoman Empire to join Germany and its allies.

Turkey Joins the War

France and Russia tried to keep the Ottoman Empire out of the war, but Germany pushed for them to join. After Souchon's daring escape to Constantinople, the Ottomans ended their naval agreement with Britain on August 15, 1914. The British naval mission left by September 15.

Finally, on October 29, Admiral Souchon took Goeben, Breslau, and a group of Turkish warships and attacked Russian ports in the Black Sea Raid. This attack led to a major political crisis and brought the Ottoman Empire into the war.

The British navy's failure to stop Goeben and Breslau was a big embarrassment. Admirals de Lapeyrère, Milne, and Troubridge were criticized. Milne was called back from the Mediterranean and never commanded a ship again. The navy said Milne was cleared of all blame. Troubridge was put on trial in November for not chasing the Goeben. He was found not guilty because he was under orders not to fight a "superior force." However, he was never given another command at sea. He did important work helping the Serbs and commanding a force on the Danube River in 1915. He eventually retired as a full Admiral.

Long-Term Effects

Even though the escape of Goeben was a relatively small event, it had huge long-term consequences. It helped lead to some of the biggest naval chases of the 20th century. It also played a part in the later breakup of the Ottoman Empire into many of the countries we know today.

General Erich Ludendorff, a German military leader, wrote that he believed Turkey joining the war allowed Germany and its allies to fight for two more years than they would have on their own.

The war spread to the Middle East, with major battles in places like Gallipoli, Sinai and Palestine, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus. The war in the Balkans was also affected by the Ottoman Empire joining Germany. If the war had ended in 1916, some of the bloodiest battles, like the Battle of the Somme, might have been avoided. The United States might not have joined the war either.

The Gallipoli campaign is seen as the beginning of Australian and New Zealand national identity. This event would not have happened without the Ottoman Empire joining the war. The anniversary of the landings, April 25, is known as Anzac Day, which is the most important day to remember military casualties and veterans in Australia and New Zealand.

By allying with Germany, Turkey shared their defeat in the war. This gave the winning allies the chance to divide up the collapsed Ottoman Empire as they wished. Many new nations were created, including Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.

|

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |