Reverse Underground Railroad facts for kids

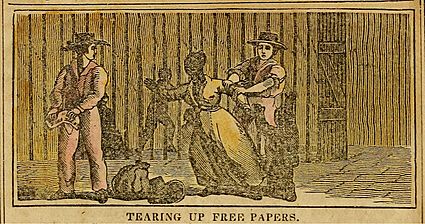

This image from 1838 shows people tearing up papers that proved a Black person was free. It also shows a free Black person being kidnapped in a Northern state to be sold into slavery in the South.

|

|

| Date | 1780–1865 |

|---|---|

| Location | Northern United States and Southern United States |

| Participants | illegal slave trader kidnappers, police, criminals, and captured free blacks |

| Outcome | Free Black people were sold into slavery, and those who had escaped slavery were forced back. This ended when the Union won the American Civil War. Slavery was then abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution later gave full citizenship rights to formerly enslaved people. |

| Deaths | Unknown |

The Reverse Underground Railroad was a cruel practice before the American Civil War. It involved kidnapping free Black people and those who had escaped slavery from "free states." These kidnapped individuals were then taken to "slave states" and sold into slavery. Sometimes, kidnappers received a reward for returning an escaped person.

The name "Reverse Underground Railroad" was used by people who supported slavery. They were angry about the actual Underground Railroad, which was a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Unlike the real Underground Railroad, the "reverse" version was not an organized network. Its activities were often out in the open. It was very rare for kidnapped Black people to be rescued.

Kidnappers used three main methods:

- Physically grabbing people.

- Tricking free Black people into being captured.

- Catching people who had escaped slavery.

This terrible practice lasted for 85 years, from 1780 to 1865. The name is a direct opposite of the Underground Railroad. That was a secret system of people who wanted to end slavery. They helped enslaved people escape to freedom, usually in Canada or Mexico, where slavery was against the law.

Contents

Where Kidnappings Happened

Free African Americans were often kidnapped from states that bordered slave states. These included Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. However, kidnappings also happened in states further north, like New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois. Even some parts of Southern states that were against slavery, such as Tennessee, saw these kidnappings.

New York and Pennsylvania

Free Black people in New York City and Philadelphia were especially at risk. In New York, a group called 'the black-birders' often captured men, women, and children. Sometimes, police officers and city officials helped them.

In Philadelphia, Black newspapers often printed notices about missing children. One notice was for the 14-year-old daughter of the newspaper's editor. Children were very easy targets for kidnappers. In just two years, at least 100 children were kidnapped in Philadelphia alone.

Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia

From 1811 to 1829, a woman named Martha "Patty" Cannon led a gang. This gang kidnapped both enslaved and free Black people from the Delmarva Peninsula. This area includes parts of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, near the Chesapeake Bay. They then transported and sold these people to plantation owners further south.

Illinois

John Hart Crenshaw was a wealthy landowner and slave trader in southeastern Illinois. He operated from the 1820s to the 1850s in Gallatin County. He was also a business partner of Kentucky lawman and outlaw, James Ford. Crenshaw and Ford were accused of kidnapping free Black people in southeastern Illinois. They then sold them into slavery in Kentucky.

Even though Illinois was a "free state," Crenshaw leased salt works in nearby Equality, Illinois from the U.S. Government. This allowed him to use enslaved people for the hard work of hauling and boiling salt brine from local springs to make salt. Because Crenshaw kept enslaved people and kidnapped free Black people to force them into slavery, his house became known as The Old Slave House.

Other kidnappings in Illinois happened in the southwestern and western parts of the state. These areas were along the Mississippi River, which bordered the slave state of Missouri. In 1860, John and Nancy Curtis were arrested. They tried to kidnap their own formerly enslaved people in Johnson County, Illinois to sell them back into slavery in Missouri. Free Black people were also kidnapped in Jersey County, Illinois and taken to be sold as slaves in Missouri.

Southern States

Black sailors who traveled to Southern states faced the danger of being kidnapped. South Carolina passed the Negro Seamen Act in 1822. This law was made because people feared that free Black sailors might inspire slave revolts. It required that free Black sailors be jailed while their ship was in port. This could lead to Black sailors being sold into slavery if their captains did not pay the jail fees. It also happened if their freedom papers were lost.

In the 1820s and 1830s, John A. Murrell led a criminal gang in western Tennessee. He was once caught with a formerly enslaved person living on his property. His method was to kidnap enslaved people from their plantations. He would promise them freedom, but then sell them to other slave owners. If Murrell was in danger of being caught with kidnapped enslaved people, he would kill them. This was to avoid being arrested for stealing property, which was a major crime in the Southern United States. In 1834, Murrell was arrested. He was sentenced to ten years in the Tennessee State Penitentiary in Nashville for stealing enslaved people.

Kidnapping Routes

In 1827, a newspaper called The African Observer shared a story. Several children from Philadelphia were tricked onto a small boat in the Delaware River. They were promised peaches, oranges, and watermelons. Instead, they were immediately put in chains below deck. They traveled by ship for a week. Once they landed, they were forced to walk through forests, swamps, and cornfields. They arrived at the home of Joe Johnson and Jesse and Patty Cannon, on the border between Delaware and Maryland. There, they were "kept in irons for a considerable amount of time."

From there, they were put on another boat for a week or more. One child heard someone talking about Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. Once they landed again, they were marched for "many hundred miles" through Alabama. They finally reached Rocky Springs, Mississippi.

The same newspaper article described a chain of "Reverse Underground Railroad" stops. These stretched "from Pennsylvania to Louisiana."

In the West, kidnappers traveled on the Ohio River. They stole enslaved people in Kentucky and kidnapped free people in Southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. These victims were then taken to slave states.

Travel Conditions

Many kidnapped Black people were forced to march to the South on foot. The men were often chained together to stop them from escaping. Women and children usually had fewer restrictions.

Stopping Kidnappings and Rescues

As early as 1775, Anthony Benezet and others in Philadelphia formed a group. This group was later renamed the biracial Pennsylvania Abolition Society. In 1827, The Protecting Society of Philadelphia was created. It was an offshoot of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Its goal was to prevent kidnapping and "man-stealing."

In January 1837, The New York Vigilance Committee reported its work. This group was formed because any free Black person was at risk of being kidnapped. They stated they had protected 335 people from slavery. David A. Ruggles, a Black newspaper editor and the group's treasurer, wrote about his efforts. He tried to convince two New York judges to stop illegal kidnappings, but failed. He also wrote about a brave and successful rescue of a young girl named Charity Walker from her captors' home in New York.

State and city governments found it hard to stop kidnappings. This was true even before the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society compared records of captured Black people. They tried to free those who were wrongly held. They also kept a list of missing people who might have been kidnapped. They formed a Committee on Kidnapping. However, these efforts were expensive and hard to keep going.

Citizens, especially free Black citizens, actively pushed local governments to create stronger laws against kidnapping. In 1800, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones sent a petition to Congress. It was signed by 73 important free Black citizens. They urged Congress to stop the kidnappings, but it was ignored. Because government groups were not very effective, free Black people often had to protect themselves and their families. They carried proof of their freedom with them at all times. They also avoided strangers and certain areas. Groups of citizens also formed to fight kidnappers, including Black kidnappers. The free African-American community strongly condemned Black kidnappers.

From Philadelphia, a high constable named Samuel Parker Garrigues made several trips to Southern states. He did this at the request of Mayor Joseph Watson. His goal was to rescue children and adults who had been kidnapped from Philadelphia's streets. He also successfully went after their kidnappers. One case involved Charles Bailey, who was kidnapped at age fourteen in 1825. Garrigues finally rescued him after a three-year search. Sadly, the beaten and very thin youth died a few days after being brought back to Philadelphia. Garrigues was able to find and arrest Bailey's kidnapper, Captain John Smith, also known as Thomas Collins. He was the head of "The Johnson Gang." Garrigues also tracked down and arrested John Purnell of the Patty Cannon gang. Mayor Watson announced the hunt for the kidnappers in several newspapers, offering a $500 reward. In one instance, a brave 15-year-old Black boy named Sam Scomp spoke out about his kidnapping. This happened during his attempted sale to a white Southern planter named John Hamilton. The planter himself contacted Mayor Watson to arrange a rescue for Sam and another kidnapped youth.

In Popular Culture

In 1853, Solomon Northup published Twelve Years A Slave. This was his true story about being kidnapped from New York. He spent twelve years as an enslaved person in Louisiana. His book sold 30,000 copies when it was first released. His story was made into a 2013 film, which won three Academy Awards. A novel called Comfort: A Novel of the Reverse Underground Railroad by H. A. Maxson and Claudia H. Young, came out in 2014.

Publications that supported ending slavery often used stories of people kidnapped into slavery. These stories showed how terrible slavery was. Important works that shared these accounts include The African Observer. This was a monthly publication that used firsthand stories to show the evils of slavery. Another was Isaac Hopper's Tales of Oppression, a collection of kidnapping stories by the abolitionist Isaac Hopper.

Notable Kidnappers

- Patty Cannon and Cannon-Johnson Gang

- John Hart Crenshaw

- John A. Murrell

- "Uncle Bob" Wilson

Notable Victims

Gallery

-

This 1834 image from a Boston anti-slavery book shows a free Black person being kidnapped in a Northern state to be sold into slavery in the South.

-

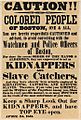

This poster from April 24, 1851, warned the "Colored People of Boston" that policemen were acting as "Kidnappers and Slave Catchers."

-

John A. Murrell from western Tennessee.

-

John Hart Crenshaw, from southeastern Illinois, with his wife, Francine "Sina" Taylor.

-

John Hart Crenshaw's Hickory Hill mansion, in Gallatin County, Illinois, famously known as the "Old Slave House."

-

Solomon Northup, a free Black man born in New York who was later kidnapped by slave catchers.

-

An illustration from Twelve Years A Slave, the true story of Solomon Northup, 1853: "Rescues Solomon from Hanging."

See also

In Spanish: Ferrocarril Subterráneo Inverso para niños

In Spanish: Ferrocarril Subterráneo Inverso para niños

- Black Codes (United States)

- Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

- Judicial aspects of race in the United States

- Jim Crow laws

- Delphine LaLaurie

- Solomon Northup

- Racial segregation in the United States

- Slave catcher

- Slave codes

- Sundown town

- Slavery in the United States

- Underground Railroad

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |