Ruhollah Khomeini facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ruhollah Khomeini

|

|

|---|---|

| روحالله خمینی | |

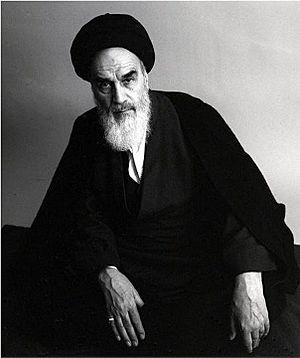

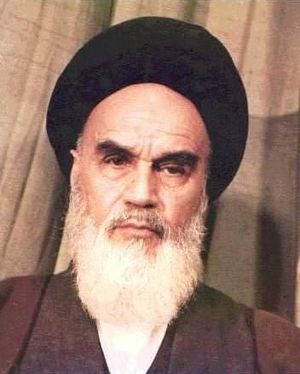

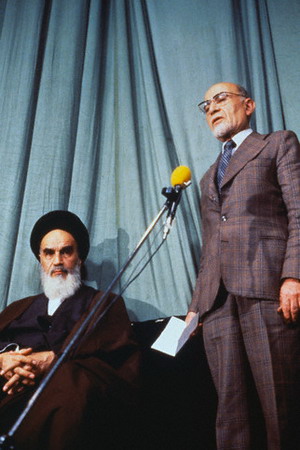

Khomeini around 1980s

|

|

| 1st Supreme Leader of Iran | |

| In office 3 December 1979 – 3 June 1989 Head of State: 11 February 1979 – 3 December 1979 |

|

| President | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Deputy | Hussein-Ali Montazeri (1985–1989) |

| Preceded by | Office established Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as Shah of Iran |

| Succeeded by | Ali Khamenei |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Ruhollah Mostafavi Musavi

17 May 1900 Khomeyn, Sublime State of Persia |

| Died | 3 June 1989 (aged 89) Tehran, Iran |

| Resting place | Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Spouse |

Khadijeh Saqafi

(m. 1929) |

| Children |

|

| Signature |  |

| Website | www.imam-khomeini.ir |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Twelver Shīʿā |

| Alma mater | Qom Seminary |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | Grand Ayatollah |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Ayatollah Seyyed Hossein Borujerdi |

| Styles of Ruhollah Khomeini |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | Eminent marji' al-taqlid, Ayatullah al-Uzma Imam Khumayni |

| Spoken style | Imam Khomeini |

| Religious style | Ayatullah al-Uzma Ruhollah Khomeini |

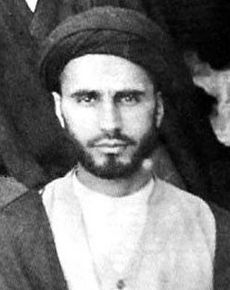

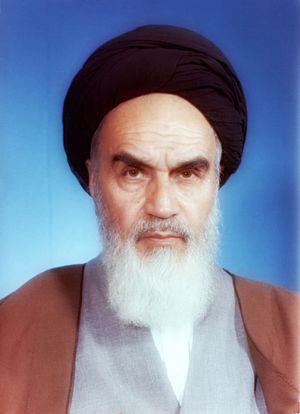

Ruhollah Khomeini (born Ruhollah Mostafavi Musavi; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989), also known as Ayatollah Khomeini, was an important Iranian leader. He was a religious scholar who became the first Supreme Leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He founded the Islamic Republic of Iran. He also led the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which removed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi from power. After the revolution, Khomeini became the country's top political and religious authority. Much of his time in power was during the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988). Ali Khamenei became his successor in 1989.

Khomeini was born in Khomeyn, Iran. His father passed away when Khomeini was two years old. He started studying the Quran and Arabic at a young age. His relatives helped him with his religious studies. Khomeini was a high-ranking religious leader called an Ayatollah. He wrote over 40 books. He lived in exile for more than 15 years because he opposed the Shah. He was named Time magazine's Man of the Year in 1979. Khomeini is often seen as a key figure in Shia Islam in Western culture. He is officially known as Imam Khomeini in Iran. His tomb in Tehran is a special place for his followers.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Family Background

Ruhollah Khomeini came from a family of landowners, religious scholars, and merchants. His family moved from Iran to India in the late 1700s. They later settled in a town called Kintoor. Khomeini's grandfather, Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi, was born in India. He left India in 1830 to visit a holy site in Iraq. He then settled in Khomein, Iran, in 1839. Khomeini even used "Hindi" as a pen name in some of his poems.

Childhood and Early Education

Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini was born on 17 May 1900 in Khomeyn. His first name means "spirit of Allah." He was raised by his mother and aunt after his father passed away in 1903.

Ruhollah started learning the Qur'an and basic Persian at age six. The next year, he went to a local school. There, he learned about religion and other traditional subjects. He continued his religious education with help from his relatives throughout his childhood.

Advanced Studies and Teaching

After World War I, Khomeini decided to study at the Islamic seminary in Arak. He studied under Ayatollah Abdolkarim Haeri Yazdi. In 1920, Khomeini moved to Arak to begin his studies. The next year, his teacher moved to the holy city of Qom and invited his students to follow. Khomeini accepted and moved to Qom.

Khomeini studied Islamic law and religious rules. He also became interested in poetry and philosophy. He learned from several important teachers in Qom. He was influenced by ancient Greek thinkers like Aristotle and Plato. Among Islamic philosophers, he was mainly influenced by Avicenna and Mulla Sadra.

Besides philosophy, Khomeini loved literature and poetry. His poetry collection was published after his death. He wrote mystic, political, and social poems from his teenage years. A modern poet, Nader Naderpour, said Khomeini could recite many lines of poetry.

Ruhollah Khomeini taught at religious schools for many years. He became a leading scholar of Shia Islam. He taught political philosophy, Islamic history, and ethics. Many of his students later became important Islamic thinkers. As a teacher, Khomeini wrote many books on Islamic philosophy, law, and ethics. He was especially interested in philosophy and mysticism, which were not common subjects in religious schools.

Opposition to the Shah

Early Political Views

Khomeini's teaching often focused on how religion was important for daily social and political issues. He worked against secularism (keeping religion separate from government) in the 1940s. His first political book, Kashf al-Asrar (Uncovering of Secrets), was published in 1942. It criticized ideas that went against religious teachings. He also listened to Ayatullah Hasan Mudarris, a leader who opposed the government in the 1920s. Khomeini became a marja' (a religious authority) in 1963.

The White Revolution

In January 1963, the Shah announced the "White Revolution." This was a plan of reforms for Iran. It included changes like land reform, selling state businesses, and allowing women to vote. Many religious scholars, called the ulama, saw these changes as dangerous. They believed the changes were too Western and went against Islamic traditions. Khomeini saw them as "an attack on Islam."

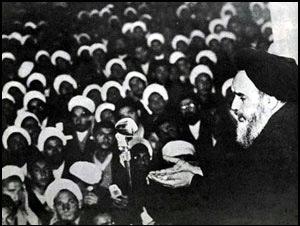

Khomeini gathered other religious leaders in Qom. He convinced them to ask people to boycott the vote on the White Revolution. On 22 January 1963, Khomeini strongly criticized the Shah and his plan. The Shah responded by sending soldiers to Qom and giving a speech against the religious leaders.

Khomeini continued to speak out against the Shah's plans. He issued a statement signed by eight other religious scholars. This statement said the Shah had broken the constitution. It also criticized the spread of corruption and accused the Shah of being too close to the United States and Israel. Khomeini also asked people to cancel the Nowruz (Iranian New Year) celebrations as a protest.

On 3 June 1963, Khomeini gave a speech. He compared the Shah to a historical tyrant. He warned the Shah that if he did not change, people would be happy to see him leave. Two days later, on 5 June 1963, Khomeini was arrested in Qom and taken to Tehran. This led to three days of large riots across Iran. About 400 people died. This event is known as the Movement of 15 Khordad. Khomeini was kept under house arrest for two months.

Opposition to Diplomatic Immunity

On 26 October 1964, Khomeini again spoke out against the Shah and the United States. This was because the Shah had given American military personnel in Iran special diplomatic protection. This meant they would be tried in U.S. courts, not Iranian courts, if they committed a crime. Khomeini called this a "capitulation law."

Khomeini was arrested in November 1964. He was held for six months. After his release, the Prime Minister, Hassan Ali Mansur, tried to make him apologize. Khomeini refused to stop opposing the Shah. Two months later, Mansur was assassinated. Members of a religious group sympathetic to Khomeini were later executed for the murder.

Life in Exile

Khomeini spent over 14 years living outside Iran. Most of this time was in the holy city of Najaf, Iraq. He was first sent to Turkey in November 1964. In October 1965, he was allowed to move to Najaf. He stayed there until 1978, when he was forced to leave by Saddam Hussein. By this time, many Iranians were unhappy with the Shah. Khomeini then moved to Neauphle-le-Château, a suburb of Paris, France, in October 1978.

By the late 1960s, Khomeini was a respected religious leader for many Shia Muslims. While in exile, he gave a series of lectures on Islamic government. These were later published as a book called Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist.

In this book, he shared his ideas on how a country should be run:

- Laws should only come from God's laws (called Sharia). These laws cover all parts of human life.

- Since Sharia is the right law, government leaders should understand it. Religious scholars (called faqih) know the most about Sharia. So, the country's ruler should be a faqih who is the most knowledgeable.

- This system of religious rule is needed to stop injustice, corruption, and oppression. It also helps protect Islam from outside influences.

A version of this system was put in place after Khomeini came to power. He became the first "Guardian" or "Supreme Leader" of the Islamic Republic. While in exile, Khomeini carefully shared his ideas for religious rule. He built a network of people who opposed the Shah. In Iran, the Shah's actions, like stopping protests, made more people oppose him.

Recordings of his speeches criticizing the Shah became popular in Iran. This helped to weaken the Shah's image. Khomeini also reached out to other groups who opposed the Shah, even if they had different ideas.

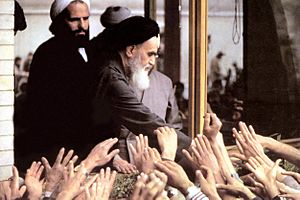

After the death of Ali Shariati in 1977, Khomeini became the most important leader against the Shah. People in Iran started to see him as a very special figure. A rumor spread that his face could be seen in the full moon. Millions believed it, and it was celebrated in mosques. Many Iranians saw him as both a spiritual and political leader of the revolution.

As protests grew, Khomeini's importance increased. Even from Paris, he guided the revolution. He told Iranians not to give up and to stop working to protest the government. In his last months of exile, many reporters and supporters visited him.

Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Return to Iran

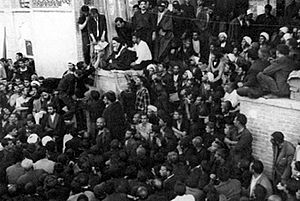

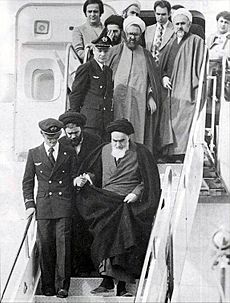

Khomeini was not allowed to return to Iran while the Shah was in power. On 16 January 1979, the Shah left the country for medical treatment and never returned. Two weeks later, on 1 February 1979, Khomeini returned to Iran. Millions of people welcomed him. On his flight back to Tehran, a journalist asked him how he felt. Khomeini replied, "Hichi" (Nothing). This answer was discussed a lot. Some thought it showed his deep spiritual beliefs. Others saw it as a warning to those who hoped he would be a regular political leader.

Khomeini strongly opposed the temporary government of Shapour Bakhtiar. He said, "I appoint the government." On 11 February, Khomeini named Mehdi Bazargan as his own interim prime minister. He said that obeying Bazargan was like obeying God.

As Khomeini's movement grew, soldiers began to join his side. Khomeini said bad things would happen to troops who did not surrender. On 11 February, the military declared it would stay neutral, and the Shah's government collapsed. On 30 and 31 March 1979, Iranians voted to replace the monarchy with an Islamic Republic. 98% voted in favor.

Creating the Islamic Constitution

In Paris, Khomeini had promised a democratic government for Iran. But once in power, he pushed for a religious government based on his ideas. This led to many secular politicians being removed. Khomeini and his allies took steps to create a new system. They set up Islamic Revolutionary courts and changed the military and police. They put religious scholars in charge of writing a new constitution. This constitution gave a central role to religious leaders. They also created the Islamic Republic Party to establish a religious government. All secular laws were replaced with Islamic laws.

Khomeini and his supporters worked to limit other groups. Some newspapers were closed, and protesters were attacked. Opposition groups were banned. Khomeini's supporters won most seats in the Assembly of Experts, which revised the constitution. The new constitution included a Supreme Leader who would be a religious scholar. It also created a Council of Guardians to check if laws were Islamic and to approve candidates for office.

In November 1979, the new constitution was approved by a national vote. Khomeini became the Supreme Leader. He was officially called the "Leader of the Revolution." On 4 February 1980, Abolhassan Banisadr was elected as the first president of Iran. Some critics felt Khomeini had gone back on his promise to only advise the country, not rule it.

Hostage Crisis

On 22 October 1979, the United States allowed the Shah, who was ill, to enter the country for cancer treatment. In Iran, many people were angry. Khomeini and other groups demanded the Shah be returned to Iran for trial.

On 4 November, a group of Iranian college students took over the American Embassy in Tehran. They held 52 embassy staff hostage for 444 days. This event is known as the Iran hostage crisis. In the United States, this was seen as a serious violation of international law. It caused strong anger against Iran.

In Iran, the takeover was very popular and supported by Khomeini. Taking over the embassy of a country he called the "Great Satan" helped strengthen the religious government. Khomeini reportedly said this action united the people and allowed the new constitution to be passed easily. The new constitution was approved a month after the crisis began.

The crisis divided the opposition in Iran. Some supported the hostage-taking, while others opposed it. Khomeini said Iran's parliament would decide the hostages' fate. He demanded the U.S. hand over the Shah for trial. Even after the Shah died, the crisis continued. In Iran, supporters of Khomeini called the embassy a "Den of Espionage." They shared details about equipment and documents found there.

Iran–Iraq War

Soon after taking power, Khomeini called for Islamic revolutions in other Muslim countries, including Iraq. At the same time, Saddam Hussein, Iraq's leader, wanted to take advantage of Iran's weaker military. He aimed to take Iran's oil-rich province of Khuzestan.

In September 1980, Iraq invaded Iran, starting the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988). Iranians fought back fiercely, and the Iraqi advance soon stopped. By early 1982, Iran had regained almost all the land it lost. The invasion united Iranians behind the new government. It also made Khomeini's leadership stronger. After this, Khomeini refused Iraq's offer of a truce. He demanded payments and that Saddam Hussein be removed from power. The Iran–Iraq War ended in 1988.

Iran had a larger population and economy than Iraq. However, Iraq received help from neighboring Arab states, the Soviet Union, and Western countries. These countries did not want the Islamic revolution to spread. Iran also had many weapons from the Shah's time. The United States even secretly sent arms to Iran in the 1980s, despite Khomeini's anti-Western policies.

During the war, Iranians used human wave attacks, where many people would charge forward, even children. Khomeini promised they would go to paradise if they died in battle. By March 1984, many educated Iranians had left the country. This included those who fled, those executed, and those who died in the war.

In July 1988, Khomeini accepted a truce arranged by the United Nations. He said he "drank the cup of poison" by accepting it. Despite the high cost of the war, Khomeini said extending the war to overthrow Saddam was not a mistake. He wrote that they fought to fulfill a religious duty, and the outcome was not the main point.

Rushdie Fatwa

In early 1989, Khomeini issued a religious ruling called a fatwa. This fatwa called for the killing of Salman Rushdie, a British author. Rushdie's book, The Satanic Verses, published in 1988, was seen as insulting to Islam. Khomeini's fatwa said any Muslim should kill Rushdie and those involved in publishing the book.

Many Western governments criticized Khomeini's fatwa. They said it violated human rights like free speech and freedom of religion. The fatwa was also criticized for not allowing Rushdie to defend himself. Even though Rushdie expressed regret, the fatwa was not canceled.

Life Under Khomeini

When Khomeini returned to Iran in 1979, he made many promises. He spoke of a government elected by the people, where religious leaders would not interfere. He promised that no one would be homeless and that Iranians would have free services like telephone, heating, and electricity.

Under Khomeini's rule, Sharia (Islamic law) was put into practice. Islamic dress codes were enforced for men and women. Women had to cover their hair, and men could not wear shorts. Alcoholic drinks, most Western movies, and mixed-gender swimming were banned. The school curriculum was changed to be more Islamic. Broadcasting most music on Iranian radio and TV was banned by Khomeini in July 1979. This ban lasted for 10 years.

Some groups, like feminists, ethnic and religious minorities, and those with different political views, faced difficulties under the new government.

Women's Rights

Khomeini initially supported women's involvement in the revolution. However, once in power, his views on women's rights changed. He canceled Iran's 1967 divorce law. Under his rule, the minimum age for marriage was lowered to 15 for boys and 13 for girls. Laws were passed that made it harder for women to divorce. Women were required to wear veils.

At the same time, there were efforts to help women get jobs. More women worked in healthcare, education, and other fields during his time. Women's opinions on his rule were mixed. Some were upset by the increased Islamic rules, while others found more opportunities.

LGBTQ Rights

After becoming Supreme Leader in 1979, Khomeini made same-sex relations illegal. However, being transgender was seen as a medical condition that could be treated with surgery. Since the mid-1980s, the Iranian government has allowed and partly funded gender reassignment surgeries.

Economy and Emigration

Khomeini often focused on spiritual matters more than material wealth. He once said he could not believe people made sacrifices just for cheaper melons. He also reportedly said "economics is for donkeys." This lack of interest in economic policy is thought to be one reason for Iran's economic struggles after the revolution. Other reasons included the long war with Iraq, which caused debt and inflation, and international sanctions.

Poverty increased by nearly 45% during the first six years of Khomeini's rule due to the war. Many people also left Iran, including entrepreneurs and skilled workers.

Dealing with Opposition

Khomeini warned those who opposed the new government. He said they would be "oppressed." In 1983, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reportedly helped Khomeini by giving him a list of Soviet agents in Iran. This led to the execution of some suspects and the closing of the Communist Tudeh Party of Iran.

Hundreds of former members of the Shah's government and military were executed. Later, many of Khomeini's former allies, like Marxists and socialists, who opposed the religious government, were also targeted. From 1980 to 1981, large protests against the Islamic Republic Party were met with force. Thousands of Iranians were executed. This included non-political civilians and members of the Baháʼí Faith. Between 1981 and 1985, an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 people were executed.

In 1988, Khomeini ordered judges to kill political prisoners who were seen as enemies of Islam.

Minority Religions

Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians are officially recognized and protected in Iran. After his return in 1979, Khomeini issued a ruling that Jews and other minorities (except Baháʼís) should be treated well. He saw Zionism as a political movement, different from Judaism as a religion.

However, senior government jobs were only for Muslims. Schools run by non-Muslims had to have Muslim principals. Converting to Islam was encouraged. Iran's non-Muslim population has decreased. For example, the Jewish population dropped significantly.

Four out of 270 seats in parliament were set aside for the three non-Muslim minority religions. Khomeini also called for unity between Sunni and Shia Muslims.

The Baháʼí Faith was treated differently. The new government targeted Baháʼí leaders. Many prominent members were arrested and executed. About 200 Baháʼís were executed, and others were forced to convert or faced severe restrictions. Khomeini, like most conservative Muslims, believed Baháʼís were not true Muslims. He claimed they were a political group, not a religious one.

Ethnic Minorities

After the Shah left, a Kurdish group asked Khomeini for language rights and some self-rule. Khomeini said these demands were not acceptable because they would divide Iran. He said that groups like Kurds, Lurs, Turks, Persians, and Baluchis should not be called minorities because they are all "brothers." The following months saw clashes between Kurdish groups and the Revolutionary Guards. The vote on the Islamic Republic was largely boycotted in Kurdistan. Khomeini ordered more attacks later, and much of Iranian Kurdistan came under military rule.

Death and Funeral

Khomeini's health worsened in the years before his death. He passed away on 3 June 1989, after suffering several heart attacks. He was 89 years old. Ali Khamenei became his successor. Many Iranians mourned his death in the streets. Fire trucks sprayed water on the crowds to keep them cool. At least 10 mourners died from being trampled, and hundreds were injured.

Iran's official estimates say 10.2 million people lined the 32 km (20 mi) route to Tehran's Behesht-e Zahra cemetery for his funeral on 11 June 1989. Western sources estimated about 2 million people paid their respects.

Khomeini's first funeral on 4 June had millions of attendees. It was postponed because a huge crowd rushed the procession. They destroyed his wooden coffin to get a last look or touch. Soldiers had to fire warning shots to control the crowds. At one point, Khomeini's body fell to the ground as people tried to grab pieces of his burial shroud.

The second funeral was held five hours later with much tighter security. This time, Khomeini's coffin was made of steel. In 1995, his son Ahmad was buried next to him. Khomeini's grave is now inside a large mausoleum complex.

Succession

Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri, a former student of Khomeini, was chosen to be his successor in 1985. However, Montazeri began to call for more freedoms in 1989. After a letter of his complaints was leaked, Khomeini removed him as his official successor.

To find a new leader, Iran's constitution was changed. This allowed Ali Khamenei, who had strong revolutionary ties but was not a Grand Ayatollah, to become the new leader. Ayatollah Khamenei was elected Supreme Leader on 4 June 1989.

Anniversary

The anniversary of Khomeini's death is a public holiday in Iran. People visit his mausoleum to pray and hear sermons.

Legacy and Influence

Khomeini's ideas greatly shaped politics in the Islamic Republic of Iran. His views on government changed over time. He first allowed rule by monarchs if Islamic law was followed. Later, he strongly opposed monarchy. He argued that only a leading religious scholar should rule to ensure Islamic law was followed. Finally, he said the ruling scholar did not need to be a top one. He also said Islamic law could be set aside if needed for the good of Islam and the state.

Khomeini's idea of "Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist" did not initially have the support of all leading Iranian religious scholars. Many clerics became unhappy with the Shah's rule, but not all supported Khomeini's vision of a religious republic.

There is much debate about whether Khomeini's ideas were compatible with democracy. Some believe he did not intend for the Islamic Republic to be democratic. Others, including current Iranian leaders, believe he did and that it is democratic. Khomeini himself made statements that seemed to support and oppose democracy at different times.

Khomeini presented himself as a champion of Islamic unity. He focused on issues Muslims agreed on, like fighting against Zionism and imperialism. He downplayed differences between Shia and Sunni Muslims.

Khomeini strongly opposed close ties with either Eastern or Western countries. He believed the Islamic world should be a strong, unified bloc. He saw Western culture as harmful to youth. The Islamic Republic banned or discouraged Western fashions, music, movies, and books. In the Western world, his image became a symbol of fear and distrust towards Islam.

Before taking power, Khomeini said he supported the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, once in power, he took a strong stance against those who disagreed with him. He warned opponents: "Otherwise I will break your teeth."

Many of Khomeini's ideas were seen as progressive by some intellectuals before the revolution. But once he was in power, his ideas often clashed with those of modern or secular Iranian thinkers. This conflict became clear when many newspapers were closed by the government.

Khomeini also supported international revolution and unity among developing nations. He focused on supporting non-Muslim revolutionary movements more than some conservative Islamic groups.

Khomeini's legacy on the economy was a concern for the poor, but the results did not always help them. During the 1990s, the poor and war veterans protested rising food prices. Khomeini's reported disinterest in economics ("economics is for donkeys") is said to have influenced later leaders.

In 1963, Khomeini wrote that there were no religious restrictions on surgery for transgender individuals. After 1979, this ruling became the basis for national policy. Iran now allows and partly funds gender reassignment operations.

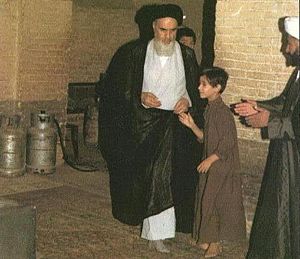

Appearance and Habits

Khomeini was described as slim and athletic. He was known for being distant and serious. He inspired admiration, awe, and fear in those around him. He rarely smiled and often ignored his audience while teaching, which added to his powerful presence.

Khomeini followed traditional Islamic rules for cleanliness. He reportedly refused to eat or drink in a restaurant unless he was sure the waiter was Muslim.

Mystique

Some say Khomeini became a semi-divine figure. He was called "The Imam," a title usually reserved for the infallible leaders of early Shia Islam. He was also linked to the Mahdi, the 12th Imam of Shia belief. One of his titles was "Deputy to the Twelfth Imam." His enemies were often called by religious terms used for enemies of the Twelfth Imam.

As the revolution grew, even some who didn't support him felt his powerful appeal. One journalist described an Iranian who complained about the regime but became worried when he heard Khomeini might be dying.

Family and Descendants

In 1929, Khomeini married Khadijeh Saqafi. Their marriage was harmonious. She passed away in 2009. They had seven children, but only five lived past infancy. His daughters married into merchant or religious families. Both his sons became religious scholars. His elder son, Mostafa, died in 1977. His son Ahmad Khomeini died in 1995. His daughter, Zahra Mostafavi, is a professor at the University of Tehran.

Khomeini had fifteen grandchildren. Some notable ones include:

- Zahra Eshraghi, a granddaughter, is married to Mohammad Reza Khatami, a reformist leader. She supports the reform movement.

- Hassan Khomeini, an elder grandson, is a cleric. He is in charge of the Mausoleum of Khomeini. He has also supported the reform movement.

- Husain Khomeini, another grandson, is a cleric who strongly opposes the current system in Iran. In 2003, he said Iranians needed freedom and would welcome American help to achieve it. He later called for an American invasion to overthrow the Islamic Republic.

- Another grandchild, Ali Eshraghi, was initially not allowed to run in the 2008 parliamentary elections. He was later allowed to run.

See also

In Spanish: Ruhollah Jomeiní para niños

In Spanish: Ruhollah Jomeiní para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |