Slavery in Colombia facts for kids

Slavery was practiced in Colombia for a long time. It existed even before the Spanish arrived, when some indigenous groups enslaved others. Later, European settlers brought enslaved people, and the practice continued among Colombians until it was finally ended in 1851. This involved buying and selling people, first among indigenous groups, then by Europeans, and later by Colombians themselves.

Contents

Slavery of Indigenous Peoples

Before the Spanish came to what is now Colombia, some indigenous groups enslaved their neighbors. For example, the Chibchas, Muzos, and Panches enslaved people from other groups. When the Spanish arrived, they saw these practices. They decided to introduce Christianity and change these ways.

As the Spanish conquered new lands, they often enslaved people they defeated in wars. This was a common practice for them. However, the Spanish Crown later created laws to protect indigenous people. The Burgos Laws in 1512 officially ended the enslavement of indigenous people.

Later, the New Laws of 1542 brought even more protections. These laws said that indigenous people were free and should not be enslaved. They also stated that those who sold enslaved indigenous people would be punished. The New Laws aimed to treat indigenous people with kindness and peace. They even allowed for pardons for those who had rebelled.

These laws were very important. They showed that the Spanish government wanted to protect indigenous people from harsh treatment.

African Slavery

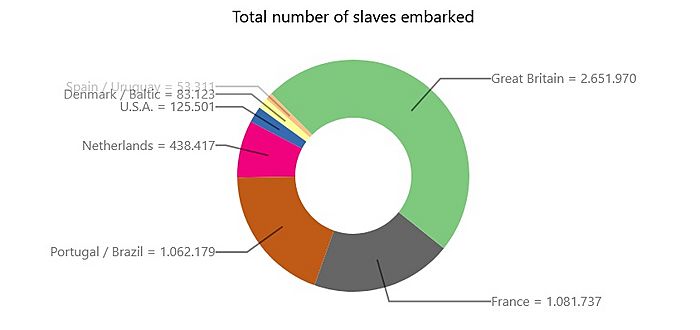

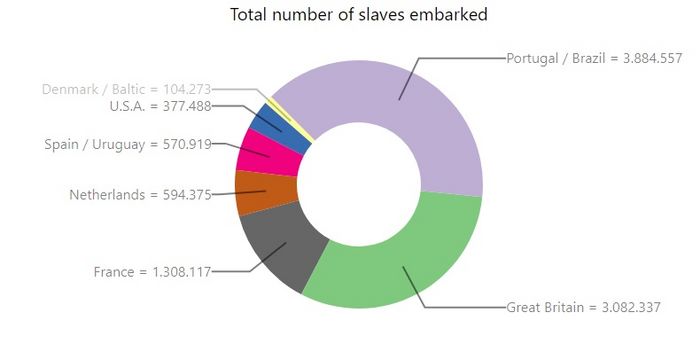

The trade of enslaved people from Africa started with the Portuguese. They transported captives to islands like Madeira and the Azores. In 1479, the Treaty of Alcáçovas recognized Portugal's lead in this trade. This made them the main suppliers of enslaved labor for many centuries.

When Europeans colonized the New World, they needed many workers. The native population was not enough, and many indigenous people died from diseases or harsh treatment. So, a large-scale trade of enslaved Africans to areas like the Viceroyalty of New Granada (which included Colombia) began in the mid-1500s. This trade was allowed through special contracts called licencias, where the Crown permitted the trade in exchange for taxes.

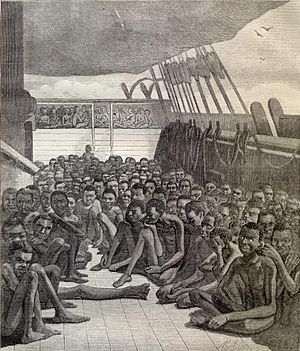

People at the time tried to justify slavery by saying that enslaved people would become Christian. However, enslaved people were transported in terrible conditions. The journey from Africa to America often lasted about two months. Ships were overcrowded, had poor ventilation, and were full of diseases.

Origins of Enslaved Africans

The first Portuguese explorers captured Africans directly. But this was difficult. So, they started using trading posts. Here, they exchanged goods with local leaders for people who had been captured and enslaved.

Most enslaved Africans brought to the New World came from West Africa. This area is between the Senegal and Cuanza rivers. It is hard to know the exact ethnic groups of enslaved people. Records often only showed the port where they were taken from.

Historians group their origins into larger regions. One way is to divide them into Sudano-Sahelian, tropical forest, and equatorial rainforest regions. Another way is Upper Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Angola region. These regions contained many different peoples.

The western Sahel region was home to groups like the Fulani, Mande, and Songhai. Large empires like the Empire of Ghana, Empire of Mali, and Songhai Empire were in this area. Many enslaved people from this region were Muslim.

In the Gulf of Guinea region, there were groups like the Kwe people and speakers of Volta-Niger languages. Smaller states like the Ashanti Kingdom were here. Peoples like the Yoruba, Igbo, and Ashanti people came from this area. Some Afro-Caribbean religions in Colombia, like Santeria, have roots in the Yoruba religion.

The southernmost region, near the Congo river delta and Angola, had mostly Bantu-speaking people. These included Kikongo and Kimbundu speakers. The Kingdom of Kongo was in this area. Its king, Afonso I, tried to stop the slave trade from his land. He wrote to the King of Portugal about the harm caused by slavers.

Slavery on the Caribbean Coast

Cartagena de Indias was the most important port for enslaved people in Colombia during colonial times. By 1620, about 1,400 of the city's 6,000 residents were enslaved Africans. By 1686, this number grew to 2,000. In the late 1700s, enslaved people made up about 10% of the population in Santa Marta Province and 8% in Cartagena Province.

Enslaved labor was vital for the economy in the Cartagena Province. After many indigenous people died, African labor became very important. In the 1600s, enslaved people worked in both farming and raising animals. Later, they were mainly used for livestock, as it was more profitable for slave owners.

In cities like Cartagena and Mompós, owning enslaved people also showed a family's wealth. Rich Spanish families had many enslaved servants. In the 1600s, an enslaved person could be traded for 200 to 400 silver pesos.

The system needed a constant supply of new enslaved people. This was because the enslaved African population in the New World did not grow much. More men were brought than women (about 5 men for every 1 woman), and many workers died. This meant new enslaved people, called "Bozales" (born in Africa), had to be brought in regularly.

Slavery in the Cartagena province began to decline in the 1700s. After Colombia became a republic, slavery decreased, especially in rural areas. Cheaper labor from mixed-race people replaced enslaved labor. In cities, slavery lasted longer because it was linked to social status. It continued until its abolition in the 1800s.

Slavery on the Pacific Coast

The first attempts to use enslaved Africans for mining on the Pacific coast of New Granada happened in the 1600s. But these were small and often failed because the Spanish struggled to control the native populations. Large mining operations and the massive arrival of enslaved Africans to the west coast only began in the late 1600s.

Most enslaved Africans who reached the Pacific came through the port of Cartagena de Indias. In the Pacific, an enslaved person born in Africa was worth about 300 silver pesos. Those born in the New World were worth 400 to 500 pesos. Records show that over half of the enslaved people in Chocó were of Kwa origin, mainly from the Akan and Ewe groups. There were also smaller groups of Mandé, Gur speakers, and Kru.

The Pacific coast had the highest percentage of enslaved people in New Granada. A census from 1778–1780 showed that enslaved people made up 39% of the population in Chocó, 38% in Iscuandé, 63% in Tumaco, and an amazing 70% in Raposo (modern-day Buenaventura).

These enslaved people were crucial for gold mining in the Pacific Region. Between 1680 and 1700, Popayán produced 41% of all gold in New Granada.

Rebellions Against Slavery

Indigenous Rebellions

Indigenous peoples were the first to fight against forced labor by Europeans. In the 1500s, groups like the Paeces, Muzos, and Yariguis rebelled. The Chinantos rebelled against San Cristóbal, and the Tupes against Santa Marta.

The Pijaos were very successful in their resistance. They managed to stop mining in Cartago and Buga. They also cut off communication with Popayán and Peru and even killed the Governor of Popayán. This war in the early 1600s ended with a European victory. Those who helped the Europeans were rewarded with land and labor rights called encomiendas.

African Rebellions

Enslaved Africans often rebelled against their masters. They did this by running away to form free communities, a practice called cimarronaje, or through armed uprisings. In Santa Marta in 1530, just five years after the city was founded, a rebellion by enslaved people destroyed the town. The city was rebuilt, but another rebellion happened in the 1550s.

While some enslaved individuals ran away alone, it was risky. Many organized their escapes and went to Maroon communities. In these communities, they could find safety and support from others who had also escaped.

Not all rebellions ended in escape. Sometimes, the threat of revolt was used to negotiate better treatment. In 1768, in Santa Marta, a group of enslaved people injured a foreman they accused of mistreatment. When their master sent men to stop them, the enslaved people killed one. The rebels then gave their master an ultimatum: if he didn't meet their demands, they would burn down the estate and escape to live with "brave Indians." The master had to agree. He promised to forgive them, stop the mistreatment, and sell families together if they were sold. He also gave them tobacco and brandy as compensation.

Similar events happened in Neiva in 1773 and Cúcuta in 1780. In these cases, enslaved people had agreements with Jesuit priests for better treatment, like free peasants. They received payment for their crops and had holidays. When a new master refused to honor these agreements, they rebelled and demanded their rights from the colonial government.

Enslaved black women also resisted by using legal demands to challenge colonial power.

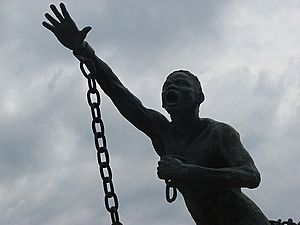

However, the most famous rebellion in New Granada was led by Benkos Biohó in San Basilio de Palenque. This rebellion was so successful that on August 23, 1691, the King of Spain had to issue a document. It ordered general freedom for the people of Palenque and recognized their right to land.

At the end of the 1600s, colonial authorities tried to fight the Maroon Palenques again. Even though they destroyed some villages, the campaign failed. The black communities kept their freedom and simply moved south.

Cimarronaje continued until slavery was abolished in the 1800s. After abolition, former enslaved people found new ways to resist. They roamed the fields, tore down fences, raided property, and punished conservatives. President José Hilario López called this period "The democratic frolics."

Abolition of Slavery

Ending slavery was a slow process. Some enslaved individuals were freed throughout the colonial period. But ending slavery as a whole institution was not seriously discussed until the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1809. At that time, the idea of freedom was raised to prevent enslaved people from fighting for it violently. Antonio Villavicencio supported freeing children born to enslaved mothers, but his ideas were not followed by the Spanish Crown.

During the Colombian War of Independence, Simón Bolívar suggested in 1816 that enslaved people who fought for independence should be freed. This was a debated idea because landowners depended on enslaved people for work and social status. They strongly opposed freeing them.

To compromise with slave owners, José Félix de Restrepo helped pass a law in the Congress of Cúcuta. This law, called "freedom of wombs," declared that children born to enslaved mothers after July 21, 1821, would be free. However, the law also said that masters had to "Educate, clothe and feed the children." In return, these children had to work for their mothers' masters until they were 18 to pay for their upbringing. The slave trade was officially banned in 1825.

The freedom for young enslaved people was supposed to start on July 21, 1839. But the War of the Supremes (1839-1842) delayed this. After the war, slave owners pressured the government. A new law on May 29, 1842, extended the dependence of enslaved people for another 7 years. This was called "apprenticeship." Enslaved people who turned 18 had to serve their former master or someone else who could "educate and instruct" them in a trade. This extended slavery. Those who refused were forced into the national army.

The process of freeing enslaved people was slow and had problems. Officials and landowners sometimes ignored the law and continued the slave trade. This made many people, especially liberal artisan groups called Democratic Societies, very unhappy. This political unrest, from both artisans and enslaved people, led President José Hilario López to propose complete freedom.

Finally, the Colombian Congress passed a law on May 21, 1851. This law declared that all enslaved people would be free starting January 1, 1852. Masters would receive compensation with bonds.

Even with the law, many masters refused to free enslaved people peacefully. This led to the Civil War of 1851. It began with uprisings in Cauca and Pasto, led by Conservative leaders Manuel Ibáñez and Julio Arboleda, with support from Ecuador. In Antioquia, the rebellion was led by conservatives like Eusebio Berrero. The war ended in four months with a liberal victory and the final liberation of enslaved people.

The number of enslaved people decreased over time until slavery was completely abolished:

| Year | Total Population (#) | Enslaved People (#) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1778 | 798,956 | 62,547 | 7.82% |

| 1825 | 1,129,174 | 45,133 | 4.00% |

| 1835 | 1,570,854 | 37,547 | 2.39% |

| 1843 | 1,812,782 | 25,591 | 1.41% |

| 1851 | 2,105,622 | 15,972 | 0.76% |

See also

In Spanish: Esclavitud en Colombia para niños

In Spanish: Esclavitud en Colombia para niños

- Afro-Colombians

- Slavery in Brazil

- Slavery in Canada

- Slavery in Colonial America

- Slavery in Latin America

- Slavery in New Spain

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |