Sleaford facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sleaford |

|

|---|---|

| Town and civil parish | |

|

Clockwise from top: Aerial of Sleaford Castle site, Handley Monument, St Deny's Church, view across rooftops of Sleaford and Sessions House (on the right) |

|

| Population | 19,807 (2021 Census) |

| OS grid reference | TF064455 |

| • London | 100 mi (160 km) S |

| District |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SLEAFORD |

| Postcode district | NG34 |

| Dialling code | 01529 |

| Police | Lincolnshire |

| Fire | Lincolnshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| EU Parliament | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament |

|

| Website | www.sleaford.gov.uk |

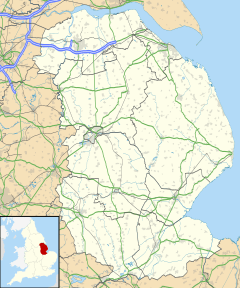

Sleaford is a lively market town in Lincolnshire, England. It's located on the edge of a flat, low-lying area called the Fenlands. Sleaford is about 11 miles (18 km) north-east of Grantham and 17 miles (27 km) south of Lincoln. With a population of 19,807 in 2021, it's the largest town in the North Kesteven district.

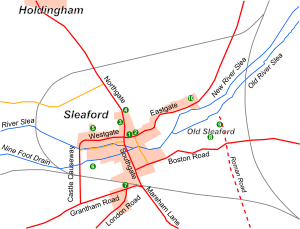

The town includes areas like Quarrington and Holdingham. Major roads like the A17 and A15 bypass Sleaford, connecting it to other important towns. Sleaford railway station also links the town to places like Nottingham, Skegness, and Peterborough.

Sleaford's history goes way back to the Iron Age, when a settlement grew where a path crossed the River Slea. It was even a tribal center with its own coin mint! Over time, it became a busy market town, especially known for its wool trade. Later, canals and railways helped Sleaford grow, bringing new industries and jobs. Today, Sleaford is an important center for shopping, services, and local government in its area.

Contents

Geography

What is Sleaford's Landscape Like?

Sleaford is the main market town in the North Kesteven area of Lincolnshire. The town's boundaries include Holdingham to the north-east and Quarrington to the south-east, which have both grown into the main town. Sleaford is about 43 feet (13 meters) above sea level. It sits near the Lincoln Cliff, a limestone ridge running through the county.

The ground beneath Sleaford is made up of different types of rock. The western part has Sandstone, Limestone, and clay rocks from 168-165 million years ago. The eastern part has younger clay formations from 165–156 million years ago. You can find Alluvium (river deposits) along the Slea River and sand and gravel to the east and south.

Lincolnshire's land is mostly "very good" for farming. This means a lot of crops and vegetables are grown here. Sleaford is also on the edge of the Fens, a low-lying area that used to be marshy. After being drained over centuries, these lands now have very rich soil, making them some of the most productive farmlands in the country.

What is Sleaford's Climate Like?

The British Isles have a maritime climate, which means cool summers and mild winters. Lincolnshire, being on the east side, often gets more sunshine and warmth than the national average. It's also one of the driest counties in the UK.

The average temperature in the East of England is about 9°C to 10.5°C. The highest temperature ever recorded in the region was 37.3°C in August 2003. On average, the area has about 30 rainy days in winter and 25 in summer. Thunderstorms happen about 15 days a year, and hail about 6–8 days. Sleaford has even seen golf-ball-sized hail!

While strong winds are less common, tornadoes happen more often in the East of England than elsewhere. Sleaford experienced tornadoes in 2006 and 2012, both causing some damage to buildings.

| Climate data for Cranwell 1981–2010 62 m asl (weather station 3.5 miles (6 km) to the NW of Sleaford) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.5 (70.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.1 (39.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 50.9 (2.00) |

36.3 (1.43) |

41.6 (1.64) |

47.3 (1.86) |

50.1 (1.97) |

56.6 (2.23) |

54.0 (2.13) |

58.1 (2.29) |

51.9 (2.04) |

58.0 (2.28) |

53.9 (2.12) |

49.9 (1.96) |

608.6 (23.96) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 64.1 | 81.3 | 115.4 | 153.5 | 200.7 | 187.0 | 200.3 | 187.5 | 147.9 | 117.0 | 72.8 | 59.6 | 1,587.1 |

History

Where Did the Name Sleaford Come From?

The name Sleaford comes from old English words. Slioford or Sliowaford were used in early records from the 9th century. In the 11th century, it was called Eslaforde. The name means 'ford over a muddy or slimy river'. A ford is a shallow place where you can cross a river.

Sleaford's Earliest Days

People have lived in the Sleaford area since the Bronze Age. The first permanent settlement started in the Iron Age. It was built where a path from Bourne crossed the River Slea. Archaeologists have found many small pieces of clay molds, likely used for making coins. These date from 50 BC to AD 50. This discovery suggests that Old Sleaford was a very important center for the Corieltauvi tribe during this time. It might have even been their main tribal town.

During the Roman period (AD 43–409), Sleaford was a large and important settlement. Its location near the fen-edge probably made it a key place for managing the fenland farms. A Roman road, Mareham Lane, ran through Old Sleaford. Digs there have found large stone houses, farm buildings, and ovens from Roman times.

Sleaford in the Middle Ages

After the Romans left, Anglo-Saxons settled in the area. A large Anglo-Saxon cemetery from the 6th–7th centuries has been found. It contained about 600 burials, some with signs of pagan traditions. In the 8th–9th centuries, Anglo-Saxon remains were found in the market place, showing an early settlement.

The River Slea was very important to the town's economy. It never dried up or froze. By the 11th century, there were many watermills along its banks. These mills were a major part of the local economy.

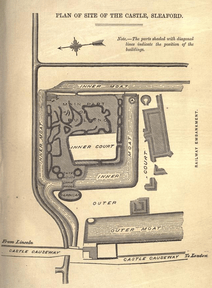

Later, the old Roman settlement became "Old Sleaford." A new town, "New Sleaford," grew up around St Denys' Church and the market place. Between 1123 and 1139, Sleaford Castle was built for the Bishop of Lincoln. The Bishop also gained the right to hold a market and fair in Sleaford in the 12th century. This helped New Sleaford grow into a busy market town. It became important in the wool trade, while Old Sleaford slowly faded away.

How Sleaford Changed in Early Modern Times

From the 16th century, the Carre family owned a lot of land in Sleaford. They had a strong influence on the town. Robert Carre founded Carre's Grammar School in 1604. His son also started Sleaford Hospital in 1636. Later, the land passed to the Hervey family. These families controlled the town's trade and charged tolls for markets.

Industry didn't grow much in Sleaford during this time. By the late 18th century, Cogglesford Mill was the only working flour mill. However, big changes happened in farming. In 1794, the town's open fields were legally enclosed. This meant that Lord Bristol, who owned most of the land, could farm it more easily. This change helped landowners but made it harder for poor villagers who used to graze their animals on common land.

Sleaford During the Industrial Revolution

In the 1790s, the River Slea was made into a canal. This was called the Sleaford Navigation. Canals made it easier to transport goods. Sleaford could export farm products and import coal and oil. This brought economic growth to the town.

However, in the mid-1850s, railways arrived. The first train line opened in 1857, connecting Sleaford to Grantham. Railways were faster and cheaper, so the canal business declined. The new transport links helped Sleaford's role in agricultural trade grow. Large seed companies and the huge Bass & Co maltings complex were built.

Sleaford's population more than doubled between 1801 and 1851. New public buildings were constructed, like the gasworks in 1839, which provided gas lighting. However, some areas of the town were very crowded and unhealthy. It took time for local leaders to improve sanitation and provide clean water.

Sleaford in Modern Times

Sleaford was mostly unharmed during the World Wars. But it has strong ties to the Royal Air Force (RAF). This is because several RAF bases, like RAF Cranwell, are nearby. Lincolnshire's flat land was perfect for building airfields during World War I. RAF Cranwell became the world's first air academy in 1920.

After World War II, new houses were built in Sleaford. The town center also saw changes, with new shopping areas opening. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a lot of farmland around Sleaford was sold for new housing estates. This caused the town's population to grow very quickly. Between 1981 and 2011, Sleaford's population more than doubled!

This rapid growth put a strain on the town's roads. New bypasses and a one-way system were introduced to help with traffic. In the early 2000s, Sleaford received a large grant to improve the town center. This included building The Hub, a creative arts center, in the old Navigation wharves area.

Economy

What Kinds of Jobs are in Sleaford?

Sleaford is the main town for jobs and services in the North Kesteven district. It's a central place for people living in the town and nearby villages. The main areas for jobs are Sleaford Enterprise Park, Woodbridge Road business park, and the town center.

Many people who live in North Kesteven also travel to other towns for work. These include Lincoln, Grantham, and Newark-on-Trent. For example, a study in 2011 found that 70% of workers living in new houses in Quarrington worked outside Sleaford.

Shopping and Services in Sleaford

Sleaford has a long history of providing services for the wider area. Even with industries growing in the 19th century, most jobs were in services and trade. In 2021, about 21% of the town's workers were in retail, hotels, and food services.

The town center has many shops and services, especially along Northgate and Southgate. There are also shopping centers like the Bristol Arcade and the Riverside Centre. Supermarkets are located both in the town center and on the outskirts.

Sleaford's traditional cattle and poultry markets closed in the 1980s. However, a weekly market is still held in the Market Place on Fridays, Saturdays, and Mondays. There's also a farmers' market once a month.

In 2011, the council noticed that Sleaford's shops and services hadn't kept up with its growing population. Many shoppers were going to other towns for more expensive items or leisure activities. The council is working on plans to improve shopping in Sleaford. This includes ideas for new shops, more parking, and making the town center more attractive.

Public Services and Government Jobs

The growth of local government and public services in the 19th and 20th centuries, along with nearby RAF bases, made the public sector very important to Sleaford's economy. In the early 20th century, Sleaford was home to the headquarters of several local councils. By 1939, 18% of the town's workers were in public administration and defense.

Today, the public sector is the biggest employer in Sleaford. In 2021, public administration, education, and healthcare made up 37% of the workforce. Sleaford is home to the headquarters of North Kesteven District Council. It also has four primary schools and three secondary schools. The nearby RAF bases at Cranwell, Digby, and Waddington are also major employers.

Industry and Business in Sleaford

Sleaford's role as a market town supported local craft industries before the mid-19th century. When the canal and then the railways arrived, Sleaford became important for moving farm products and industrial goods. Large industries like maltings, seed sorting, and farm tool makers grew in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Many heavier industries closed between the 1920s and 1960s. Since the 1950s, the local council has encouraged lighter manufacturing. Today, Sleaford has industrial areas with light manufacturing, distribution, and other businesses. In 2021, manufacturing employed 10% of Sleaford's workers. Construction employed 8.4%, and transport and distribution 6%.

Sleaford Enterprise Park and other business parks house many businesses. These include wholesalers, vehicle repair shops, furniture stores, and food producers.

Demography

How Has Sleaford's Population Changed?

| Population changes of Sleaford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population changes of New Sleaford ancient/civil parish | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1563, there were 145 households in New Sleaford. The first official census in 1801 recorded 1,596 people in New Sleaford. After the Sleaford Navigation canal opened and the economy grew, the population steadily increased. By 1851, it reached 3,539 in New Sleaford.

Population growth slowed down between the 1850s and 1880s. But it picked up again, reaching 6,427 by 1911. After World War II, Sleaford's population grew slowly at first. This was because one main landowner still owned most of the undeveloped land.

However, from the 1960s onwards, this land was sold for new houses. As a result, Sleaford's population grew very quickly. Between 1981 and 2011, the population more than doubled to 17,671. By 2021, it had risen to 19,815. This makes Sleaford the most populated area in the North Kesteven district.

Who Lives in Sleaford?

According to the 2021 census, most of Sleaford's population (96.3%) is White. Smaller groups include Asian (1.4%), Black (0.4%), and mixed (1.4%) ethnicities. This means Sleaford is less ethnically diverse than England as a whole.

In the 2011 census, 92.7% of Sleaford's residents were born in the United Kingdom. This is higher than the national average of 86.2%. Most of the remaining residents were born in other European Union countries.

In terms of religion (2011 census), 71.6% of Sleaford's population said they were religious. This is slightly higher than the national average. Christians make up the largest religious group (70.3%). Muslims are the largest religious minority, making up 0.4% of residents.

| Ethnicity (2021) and nationality and religious affiliation (2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Asian or British Asian | Black, African, Caribbean or Black British | Mixed or multi-ethnic | Other ethnicity | Born in UK | Born in EU (except UK and Ireland) | Born outside EU | Religious | Did not follow a religion | Christian | Muslim | Other religions | |

| Sleaford | 96.3% | 1.4% | 0.4% | 1.4% | 0.5% | 92.7% | 4.3% | 2.6% | 71.6% | 21.7% | 70.3% | 0.4% | 1.0% |

| England | 81.0% | 9.6% | 4.2% | 3.0% | 2.2% | 86.2% | 3.7% | 9.4% | 68.1% | 24.7% | 59.4% | 5.0% | 2.5% |

Jobs and Economic Well-being in Sleaford

| Economic characteristics of residents aged 16 to 74 (2021) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Sleaford | England |

| Economic activity | ||

| Economically active | 63.1% | 60.9% |

| Employed | 60.6% | 57.4% |

| Economically active but unemployed | 2.5% | 3.5% |

| Economically inactive | 36.9% | 39.1% |

| Industry | ||

| Agriculture, energy and water | 2.9% | 2.3% |

| Manufacturing | 10.0% | 7.3% |

| Construction | 8.4% | 8.7% |

| Retail, hotels and restaurants | 21.0% | 19.9% |

| Transport and communication | 6.0% | 9.7% |

| Financial, real estate, professional and administration | 10.6% | 17.4% |

| Public administration, education and health | 37.2% | 30.3% |

| Other | 4.0% | 4.6% |

| Occupation | ||

| Managers and directors | 11.1% | 12.9% |

| Professionals; associate professionals | 30.4% | 33.6% |

| Administrative and secretarial occupations | 9.8% | 9.3% |

| Skilled trades | 10.6% | 10.2% |

| Caring, leisure and other service roles | 10.3% | 9.3% |

| Sales and customer service roles | 7.6% | 7.5% |

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 8.8% | 6.9% |

| Elementary occupations | 11.4% | 10.5% |

In 2021, 63.1% of Sleaford's residents aged 16 to 74 were working or looking for work. This is slightly higher than the average for England. About 60.6% of people were employed. The number of people not working or looking for work was 36.9%, which is lower than the national average.

The most common jobs in Sleaford are in public administration, education, and health (37.2%). Retail, hotels, and restaurants also employ a lot of people (21.0%). Manufacturing jobs make up 10.0% of the workforce.

Sleaford's workforce is similar to England's overall. There are slightly fewer people in professional or management roles. However, there are more people in caring, leisure, and service jobs, as well as in factory and machine operating roles.

The government's Indices of Multiple Deprivation (2019) show that North Kesteven has low levels of deprivation. Most areas in Sleaford are among the least deprived in the country. However, some parts of the town center and eastern Holdingham have higher levels of deprivation.

Transport

How Do People Get Around Sleaford?

The A17 and A15 roads now bypass Sleaford. This means they go around the town instead of through it. The A17 bypass opened in 1975, and the A15 bypass was finished in 1993. These roads connect Sleaford to places like Newark, King's Lynn, and Peterborough.

Three roads meet at Sleaford's market place: Northgate, Southgate, and Eastgate. A one-way system was set up in 1994 to help traffic flow around the town center. Local bus companies, Stagecoach and Sleafordian Coaches, run public buses. There's also a special "CallConnect" service where you can book a bus when you need it.

Sleaford's Railway Connections

Railways came to Sleaford in the 19th century. The first line from Grantham opened in 1857. Later, lines connected Sleaford to Boston and other towns. Today, Sleaford is a stop on two railway lines. These are the Peterborough to Lincoln Line and the Poacher Line (from Grantham to Skegness). Grantham is a major stop on the East Coast Main Line, which means you can get to London King's Cross in about 1 hour and 15 minutes from there.

The River Slea and Its History

The River Slea was made into a canal for much of the 19th century. This project, called the Sleaford Navigation, opened in 1794. It helped trade by allowing boats to carry goods. However, when railways arrived, the canal lost business and closed in 1878. Even though it's no longer used for boats, the river still flows through Sleaford.

Public Services

Utilities and Communication in Sleaford

The Sleaford Gas Light Company started in 1838. The next year, gas lighting was provided in the town. A gasworks was built in Eastgate. This plant provided gas until 1948.

In 1879, a water company was set up to provide clean water to Sleaford. Pumping machines were installed in 1880. In 1948, the local council took over the company.

Before the 1880s, Sleaford's dirty water went straight into the River Slea. This was a problem because the river was also a source of drinking water. In the 1880s, a sewage farm was built. Cogglesford Mill was even used as a pump to send wastewater to the farm. This system was improved over the years.

In 2013, a special power station opened in Sleaford. It burns straw bales from nearby farms to create electricity. This station can power 65,000 homes and provides free heat to public buildings in the town.

Sleaford's post office moved to Southgate in 1933. A post office still operates there today. The town's telephone exchange became automated in 1967. Sleaford Library has been in its current building on the Market Place since 1987. It has sections for local and family history.

Emergency Services and Healthcare

Lincolnshire Police provides policing in Sleaford. The Lincolnshire Fire and Rescue Service handles fires. The East Midlands Ambulance Service provides ambulance services. The police station moved to Boston Road in 1998. The fire and ambulance services now share a building on Eastgate, which opened in 2018.

Sleaford has two GP (doctor) surgeries: Sleaford Medical Group and Millview Medical Centre. There are also three dental surgeries and four pharmacies. For mental health services, Ash Villa is located nearby at Greylees. The town also has two care homes for older people.

Justice System in Sleaford

For centuries, justice in Sleaford was handled by local courts. More serious crimes were heard by justices of the peace (magistrates). These courts were known as the Sleaford Bench. The magistrates met at Sessions House from 1830.

In 1971, the court system changed. More serious cases are now heard in Lincoln. Sleaford Magistrates' Court closed in 2010. Today, the closest magistrates' courts for Sleaford residents are in Lincoln and Boston.

Education

Primary Schools in Sleaford

Sleaford has four state primary schools.

- William Alvey Church of England School was founded in 1729. It became an academy in 2012. It teaches about 650 students aged 4 to 11. In 2022, it was rated "good" by Ofsted.

- St Botolph's Church of England School started in 1867. It has 406 students aged 5 to 11. Ofsted rated it "good" in 2023.

- Our Lady of Good Counsel Roman Catholic School was established in 1882. It became an academy in 2013. It has 166 students aged 4 to 11 and was rated "good" by Ofsted in 2023.

- Church Lane Primary School opened in 1908. It has a nursery and teaches 203 students aged 3 to 11. In 2014, Ofsted rated it "outstanding."

Secondary Schools in Sleaford

Sleaford has three secondary schools, all with sixth forms (for older students).

- Carre's Grammar School is a selective school for boys (with a mixed sixth form). This means students need to pass the eleven plus exam to get in. It was founded in 1604 and has 806 students. It was rated "good" by Ofsted in 2023.

- Kesteven and Sleaford High School is a selective grammar school for girls (also with a mixed sixth form). It started in 1902 and has 763 students. Ofsted rated it "good" in 2017.

- St George's Academy is a mixed-sex comprehensive school, meaning it's not selective. It opened in 1908 and has grown to have 2,319 students across two sites. Ofsted judged it "good" in 2015.

The Sleaford Joint Sixth Form allows students from all three schools to choose subjects taught at any of the schools.

Sleaford also has one private special school, Holton Sleaford Independent School. It opened in 2021 for students with social, emotional, and mental health needs. It was rated "good" by Ofsted in 2022.

Places of Worship and Religious Groups

Anglican Churches in Sleaford

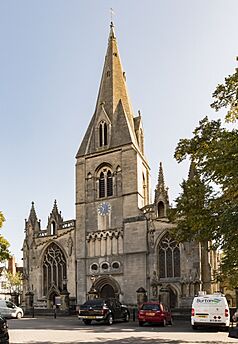

The main Anglican church in Sleaford is St Denys'. It's located by the market place. The oldest parts of the church date back to the late 12th century. Its unique broach spire is one of the oldest in England. Services are held every Sunday and Wednesday.

In the Middle Ages, Old Sleaford had its own church, St Giles's. It disappeared by the 16th century. Today, Quarrington's Anglican community uses St Botolph's Church. Parts of this church are from the 13th century.

Other Christian Churches in Sleaford

Different Christian groups have met in Sleaford for centuries.

- The Congregationalists moved to a new chapel on Southgate in 1867. Today, this is Riverside Church, which holds weekly Sunday worship.

- Wesleyan Methodists built a chapel on Westgate in 1802. They moved to North Street in 1848. Today, this is Sleaford Methodist Church, which has services every Sunday.

- The Salvation Army has been in West Banks since 1896, holding a weekly Sunday service.

- A Roman Catholic church, Our Lady of Good Counsel, opened in 1889. Mass is celebrated there on Sundays and during the week.

- Jehovah's Witnesses built their Kingdom Hall on Castle Causeway in 1972. They meet on Wednesdays and Sundays.

- Sleaford New Life Church bought a site on Mareham Lane in 2002 and built a new church. They hold Sunday worship and run a food bank.

- Sleaford Spiritualist Church opened its building on Westgate in 1956. It holds a divine service on Sundays.

Muslim Community in Sleaford

The Sleaford Muslim Community Association met in St Deny's Church Hall in the early 2000s. A prayer hall, Sleaford Islamic Centre, opened in 2015. Daily prayers are held there.

Culture

Arts, Entertainment, and Heritage in Sleaford

The National Centre for Craft & Design, also known as The Hub, opened in 2002. It's located in old seed warehouses and shows exhibitions of modern art and crafts. The Carre Gallery on Carre Street opened in 2010.

The Sleaford Museum Trust was formed to collect and save historical items from the town. A museum on Southgate opened in 2015, thanks to a grant.

The Playhouse theatre on Westgate was built in 1825. It was later used as a school and library. In 1994, Sleaford Little Theatre bought and restored it. It reopened to the public in 2000. The Sleaford Picturedrome was a cinema that opened in 1920. It closed in 2000 and has since been used as a snooker hall and nightclub. As of 2024, it's a sports bar.

Sleaford used to have an annual carnival, which was revived in 2013 for three years. The RiverLight Festival, with activities and exhibitions, has taken place every year since 2022. Sleaford Live Week is also held annually to show off local musicians and artists.

The Sleaford and District Civic Trust was founded in 1972 to help protect the town's best features. The Sleaford Rotary Club runs charity and community events. Sleaford also has a twinning association that connects it with Marquette-lez-Lille in France and Fredersdorf-Vogelsdorf in Germany.

Sports and Recreation in Sleaford

Sleaford Town F.C. is the local football club. They play in the United Counties League Premier Division North. The club was formed in 1920 and moved to its current grounds at Eslaforde Park in 2007. Sleaford Rugby FC started in 1978.

Sleaford Golf Club was founded in 1905. It has about 600 members today. Sleaford Cricket Club has grounds on London Road. The town also has several lawn bowling clubs, a gymnastics club, and running clubs like Sleaford Striders and Sleaford Town Runners.

Sleaford Leisure Centre started as an outdoor swimming pool in 1886. It was converted into a modern indoor leisure center in 1984. The center and its gym were rebuilt in 2013.

Sleaford Recreation Ground on Boston Road is the town's largest public space. It's owned and managed by Sleaford Town Council. There are also other open spaces and playgrounds managed by the council.

Local Media in Sleaford

Local news and TV programs for Sleaford are provided by BBC Yorkshire and Lincolnshire and ITV Yorkshire. Local radio stations include BBC Radio Lincolnshire and Hits Radio Lincolnshire.

The town has three local newspapers:

- Sleaford Standard (started in 1924)

- Sleaford Advertiser (started in 1980)

- Sleaford Target (started in 1984)

Landmarks

Historic Buildings in Sleaford

A few medieval buildings still stand in Sleaford. St Denys' Church and St Botolph's in Quarrington date back to the 12th and 13th centuries. Sleaford's half-timbered vicarage is from the 15th century. St Denys' Church is famous for its stone broach spire, which is one of the oldest in England.

Cogglesford Mill is the only remaining watermill in town. It shows how important the River Slea was for the economy. The Bishops of Lincoln built the now-ruined Sleaford Castle. They also helped the town grow by allowing a market. Because of this, the oldest parts of Sleaford are the market place and the four roads that meet there: Northgate, Southgate, Eastgate, and Westgate. Many buildings from the 18th and 19th centuries can be found here.

These buildings include William Alvey's house on Northgate and the Manor House, which has medieval stone. The Sessions House on the Market Place was built in 1830. The Carre family founded the grammar school, hospital, and almshouses, which were rebuilt in the 19th century.

During the Industrial Revolution, the Slea River was made into a canal in 1794. The Sleaford Navigation Company built offices and wharves along Carre Street. The canal brought trade to the town. The gasworks on Eastgate, with its Gothic front, lit the town from 1839.

The Handley family helped fund the canal and started a local bank. Henry Handley, a Member of Parliament, is remembered by the Handley Memorial on Southgate. This monument looks like an Eleanor Cross. When the railways arrived in the 1850s, the station was built in a Gothic style.

Sleaford's farming location and new transport links led to the growth of seed trading and malting. The huge Bass and Company maltings complex, built between 1892 and 1905, is a famous landmark. It's made of brick and is over 1,000 feet long.

Famous People from Sleaford

Many interesting people have connections to Sleaford:

- Benjamin Handley was a lawyer and banker who helped with the Sleaford Navigation canal. His son, Henry Handley, was a Member of Parliament.

- Sir Robert Pattinson, also educated at the grammar school, was a Member of Parliament and chairman of Kesteven County Council.

- Henry Pickworth was a religious writer born in New Sleaford.

- Richard Banister, an eye doctor, practiced in Sleaford for 14 years.

- Henry Andrews, an astronomer and astrologer, worked in Sleaford when he was young.

- The botanist David H. N. Spence was born in Sleaford.

- The royalist poet Thomas Shipman went to Carre's Grammar School.

- Joseph Smedley, an actor and comedian, built the theatre in Sleaford in 1824.

- The children's author Morris Gleitzman, actress Jennifer Saunders, and Elton John's lyricist Bernie Taupin were all born in Sleaford.

- Mark Wallington, a professional footballer, grew up in Sleaford.

Sleaford's Coat of Arms

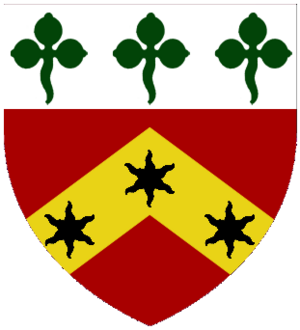

Sleaford Town Council has a special coat of arms. It was given to the town in 1950. The shield combines symbols from the Carre family and the Marquesses of Bristol, who were important landowners. The eagle in the crest represents Sleaford's connections to the Royal Air Force. The ear of wheat in the eagle's beak stands for agriculture and farming.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Sleaford para niños

In Spanish: Sleaford para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |