Social and cultural exchange in al-Andalus facts for kids

For over 700 years, Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived side-by-side in the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal). This time was known as the era of Al-Andalus states. Historians still debate how much freedom Christians and Jews truly had under Muslim rulers. However, history shows that people of these three religions generally had peaceful relationships. There were only a few small revolts and times of religious trouble. The mixing of these different groups created a unique and rich culture. This culture continued to thrive even after the Reconquista, when Christian kingdoms took back control.

Contents

Living Together in Al-Andalus

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania brought together three different religions, each with its own customs and culture. This period is often called the Convivencia, which means "culture of living together." While some historians question how much tolerance there truly was, very few major revolts or acts of violence were recorded. This doesn't mean there was no unfair treatment by Muslims at a local level. However, educated Muslims often respected Christians and Jews. They were seen as dhimmis (protected peoples) or "People of the Book" under Islamic law.

It's important to remember that the Muslim soldiers who conquered the area were a small part of the population. So, the unique Islamic society of al-Andalus grew slowly over time. To understand how these different cultures blended, we need to look at what made each group special and how they were seen in society.

Some Muslim religious leaders in Al-Andalus believed that non-Muslims were unclean. They worried that too much contact would make Muslims impure. For example, a religious scholar in Seville named Ibn Abdun made rules to keep people of different faiths separate. These rules said that Muslims should not do jobs like massaging or cleaning for Jews or Christians. They also stated that Jews and Christians should not wear clothes that looked like those of important Muslim people. Instead, they should wear special signs to show they were different. These rules show that some people held strong prejudices, even though overall relations were often peaceful.

Muslim Communities

In al-Andalus, Muslims were divided into three main groups. The largest group was the Berbers. Most Berbers came from North Africa. They usually lived in settled communities, unlike some nomadic Berber groups. After the invasion, many Berbers became farmers in the countryside. Some also moved to cities to work in crafts. All Berbers were Muslims, as their ancestors had converted to share in the wealth of Arab conquests.

The second group of Muslims was the Arabs. They were a smaller part of the total population in al-Andalus. Arabs usually held higher positions in society and made up most of the ruling class. They owned land in the richest parts of the country. They brought their language and a tradition of learning and high culture, similar to what was found in the Caliphate of Damascus.

Some historians debate how much culture these Arab invaders actually brought. Historian W. Montgomery Watt suggests that the Arabs who invaded lived a tough life before. So, they might not have had a very high level of culture themselves. Also, these Arab and Berber invaders were busy taking control. They had little time or money to spread culture on purpose. The Islamic Golden Age in Iberia also happened because of its location. It was somewhat separate from the main Umayyad Empire. The Umayyad rulers in Iberia wanted to prove they were as good as those in West Asia. This desire, combined with their need to show they were an independent region, helped culture grow. So, the invading Arabs brought some culture, but the high culture of al-Andalus's golden age came from combining and growing many different cultures in the area.

Muwalladun were Muslims of Iberian descent. They were much more numerous than those of purely Arab descent. They included people whose parents were original Arab invaders and native Iberian women. They also included people who chose to convert to Islam after the invasions. Over time, the Muwalladun adopted Arab family histories. By the 10th century, there was no clear difference between Muwalladun and Arab Muslims. By that time, Muslims made up about 80% of the total population of al-Andalus. This included Christian converts and Berber Muslims.

Christian Communities

Before and after the Muslim invasion, the Christians living in al-Andalus were mainly Visigoths, Hispano-Romans, and native Iberian tribes. The Visigoths and Hispano-Romans were the noble class before the Umayyads arrived. Most Christians were Catholic. However, some paganism and Arianism (another Christian belief) still existed in certain areas, mixing with Catholic traditions.

Under Christian Visigoth rule, a tradition of learning started in Seville by Isidore around 636 AD. Over time, Seville became a leading center of Christian knowledge in Europe. This tradition seemed to be replaced by Arabic learning after the invasion. However, it likely helped shape the Arabic traditions that grew in the peninsula.

After the Muslim invasion, Christians were classified as dhimmis under Islamic law. This status allowed them to practice their religion freely under the Umayyad dynasty. Christians could keep many of their churches. The Church organization mostly stayed the same, though some Catholic properties were taken. Bishops and other high church officials needed approval from the Caliphate before taking office.

Many Christians adopted Arabic culture. However, the traditions of the Catholic Church and the Visigoths were kept alive in monasteries by monks. The strong monastic tradition in southern Iberia continued to grow under Muslim rule. In cities, some Christians even rose to important positions in the Umayyad government.

For example, a Christian named Abu Umar ibn Gundislavus became a vizier (a high-ranking official) under Abd al-Rahman III. Another Christian, Revemund, was a secretary for the same ruler. He was later sent as an ambassador to Germany in 955–956. He eventually became the bishop of Elvira. Christian artists, especially from the Eastern Roman Empire, were also invited to work on building projects in the Caliphate of Córdoba. Some of these artists stayed and became part of Andalusian society.

While Christians lost their top position in Iberia, they could still achieve important roles under Muslim rule. However, these conditions became worse under the Almoravids and Almohads.

Jewish Communities

Jews were a small but important group in the Iberian Peninsula. They made up about 5% of the total population in al-Andalus. They began settling in the area in large numbers around the 1st century AD. Under Christian Visigothic rule, Jews faced harsh treatment. In 613, the Visigothic King Sisebut ordered Jews to convert to Christianity or be forced to leave and lose their property. So, many Jews welcomed their Muslim rulers. They saw the Muslim conquest as a rescue.

After the conquest, Jews were also classified as dhimmis under Islamic law. They had the same social standing as Christians. Jewish communities in rural areas of al-Andalus remained quite separate. However, Jews living in cities and towns, like those in Cordoba, became part of Islamic culture and society.

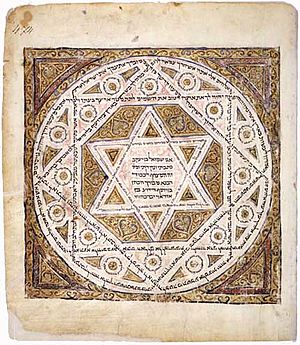

Jews came to hold very important positions in the Umayyad government. For example, the Jewish scholar and doctor Hasdai ibn Shaprut served as a diplomat for the Umayyad government. Many Jews in cities also became involved in trade as merchants. Under the Caliphate of Cordoba, Jews experienced a "Golden Age of Jewish Culture" in Spain. During this time, Jewish scholars, philosophers, and poets thrived. Jews also contributed to science and math, which were important in Cordoba at the time. Overall, Jews were treated better by the Muslim invaders than they had been under Christian rule. However, conditions worsened under Almoravid and Almohad rule.

Rules for Christians and Jews

While Christians and Jews had a good amount of religious and social freedom under Muslim rule, they did not have all the same rights as Muslims. Dhimmis, which included both Christians and Jews, had to pay a yearly tax called a jizya. If a non-Muslim owned a lot of farmland, they also had to pay the kharaj, or land tax.

There were also rules and taxes on church buildings. Certain religious practices, like parades, chanting, and ringing church bells, were limited by law. However, how strictly these laws were enforced changed from place to place. Under Islamic law, dhimmis were supposed to be in a lower position. They were not allowed to have authority over any Muslim.

But in reality, this was not always the case. Many Christians and Jews got important jobs in the Cordoban government. They worked as tax collectors, translators, and secretaries.

Still, there were many benefits to converting to Islam. People who converted could move up in society much more easily. They had a better chance to gain wealth and status. Slaves who converted to Islam by saying the Shahada (a Muslim declaration of faith) were also immediately freed.

Under the Almoravids, tensions grew. More and more rules were placed on non-Muslims. However, religious minorities still had some prosperity under their rule. Under the Almohads, these times of tolerance mostly ended. Many Christians and Jews were forced to convert to Islam or face harsh treatment. Many churches and synagogues were destroyed during Almohad rule. Many Christians and Jews moved to the Christian city of Toledo, which had recently been taken back. Overall, how different religious groups got along varied from place to place. The idea of convivencia, or a culture of tolerance, cannot be applied to all of Al-Andalus at all times.

Ibn Hazn (died 1064), a famous poet and philosopher from Cordoba, described the Christian community as "altogether vile." This shows that prejudice against Christians still existed in Al-Andalus. However, it's hard to know how widespread it was, as it changed from region to region. The invasions of the Almoravids and later the Almohads marked a change. They eventually ended the religious tolerance that had grown under the Caliphate.

Moving Up in Society and Converting to Islam

Converting to Islam often meant Christians and Jews could move up in society more easily. There isn't much information about how many Jews converted in Al-Andalus. However, the numbers are thought to be quite small. This might be because Jewish communities were very close-knit before the Muslim invasion.

Christians, on the other hand, were more willing to convert to Islam. Many wanted to get higher government jobs. Others liked Islamic teachings and culture so much that they felt they had to convert. Reports say that half of the Christians in Al-Andalus had converted to Islam by the 10th century. By the 11th century, more than 80% had converted. Many Christians who did not convert became more "Arabized" in their culture. These Christians were known as Mozarabs or musta’ribs, meaning "Arabized." They adopted the Arabic language and customs.

Even though many people converted and adopted Arab culture, which made society more similar, disagreements still happened. This led to occasional revolts and fights between the main religious groups.

Religious and Social Conflicts

When the Muslims first invaded, many Christians did resist their rule. In these early years, some kingdoms within Al-Andalus tried to stay partly independent under Muslim rule. But they were soon forced to submit. Many Christians also fled north to the mountains. They eventually formed the northern Christian kingdoms of Iberia. These kingdoms would later bring down Islamic rule in the Reconquista.

After this first struggle, strong religious feelings did not lead to any major religious revolts. For example, not a single religious revolt happened in al-Andalus during the eighth century. However, in the mid-ninth century, a small group of very religious Christians caused trouble around Córdoba. They were led by Eulogius of Córdoba, a priest who later became a Catholic saint. They encouraged Muslims to convert to Christianity and publicly spoke against Islamic teachings. Both of these actions could be punished by death under Islamic law. These outbursts were mostly linked to the Christian monastic movement and a desire for martyrdom.

Between 851 and 859, Eulogius and 48 other Christians were put to death. The movement did not get wide support from Christians in al-Andalus. After the executions, the movement died down.

Religious tolerance got worse under the Almoravids and the Almohads. Around the year 1000, Jews faced harsh treatment throughout al-Andalus, though the city of Toledo remained quite tolerant. The Almohads were especially strict with non-Muslims. Their harsh treatment of Christians and Jews caused many to leave al-Andalus.

Blended Cultures: Buildings and Art

By understanding the background and social position of each religious and ethnic group in Al-Andalus, we can see how its culture formed. It wasn't a completely new, unified culture. Instead, it was a mix of different cultures. These cultural elements have lasted through time. They are the clearest examples of this blending, seen in the art, architecture, language, and literature of Al-Andalus. The blended works created under Muslim rule in Al-Andalus led to what is known as the Golden Age of Jewish culture in Spain. They also laid the groundwork for the European Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution.

Art and Architecture

It's important to know that Islamic art and architecture are often connected. Muslim art is somewhat limited by Islamic religious rules. These rules discourage showing humans or animals in art. So, Muslim art usually avoids depicting people or animals. The art of Al-Andalus had a clear Arabic and Islamic style. It appeared mostly in sculptures and mosaics, as well as other objects that were both beautiful and useful. What made these works distinctly Andalusian was the mix of artistic elements from Catholic, Classical Roman, and Byzantine traditions.

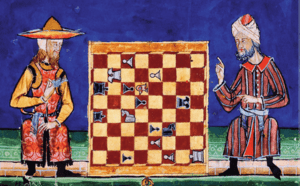

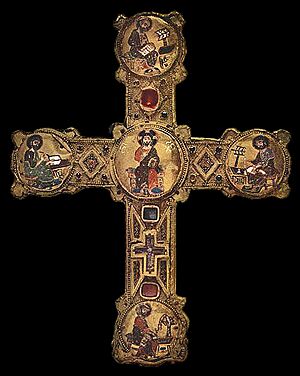

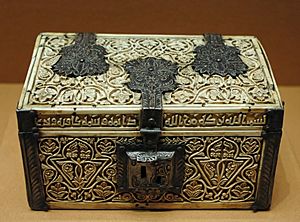

The best blend of Christian and Moorish art happened in the 11th century. This style became known as Mozarabic art. This artistic style included ceramics with mosaic work. It also used repeating patterns, often with flower-like designs, in sculptures and crafted items. Moorish ivory caskets in Al-Andalus showed signs of Western influences. Some even showed individual people and human forms, which is not typical in Islamic art.

Visigothic traditions also influenced the rulers of Cordoba. They adopted crowns in the style worn by Visigothic kings. Many of these artistic elements were used in buildings. This showed Muslim rulers' desire to connect with their ancestors in the Middle East. It also showed their Arabic heritage, even though many rulers had mixed family backgrounds. This highlights the many cultural influences that created the unique architectural style of Al-Andalus.

A famous example that shows this desire to connect with their homeland, while also reflecting their mixed culture, is the Great Mosque of Córdoba. Construction began under Abd ar-Rahman I in 784 AD and finished in 987 AD. It was partly built to show the link between Al-Andalus and the Arabs' homeland in Syria. The Great Mosque of Cordoba's design and style are very similar to the Great Mosque of Damascus (finished 715). They share many features like prayer halls, high ceilings with double-tiered arches on columns, and many mosaics. Both also have similar origin stories, which further shows Muslim attempts in Al-Andalus to feel connected to their past.

Despite these similarities, the mosque is not purely Arabic in style. It combines Roman, Byzantine, and Visigothic architectural elements. The tops of the columns and the columns themselves look like older Visigothic and Roman buildings in Cordoba. The red and white colored arches also remind us of the Roman aqueduct of Merida. The mosaics, while connected to those in Damascus, are also a mix of Christian and Arabic influences.

The artists who made these mosaics, both at the Great Mosque and at the Cordoban palace estate al-Rustafa, came from Byzantium. Another example of cultural exchange in architecture is the Madinat al-Zahra, meaning "beautiful city." It was started in 996 by Abd-ar-Raham III al-Nasir on the edge of Cordoba. It served as the capital of the Iberian Caliphate. Roman influences can be seen throughout, with an old Roman statue of a goddess in the building's gardens. Female forms also appeared on all the city gates. The column tops and columns of the palace are also in the style of Christian cathedrals. Byzantine influence is also seen throughout the palace's construction.

Byzantine artists are believed to have come to teach these skills to Andalusian artists. Some original Byzantine artists also stayed in Al-Andalus and became part of Andalusian society. Similarly, Christians and Jews adopted Arabic architectural elements into their own churches and synagogues built under Moorish rule. This became known as the Mozarabic style. Mozarabic architecture included no outside decoration, different floor plans, the use of the horseshoe arch (Islamic style), and columns for support with plant designs on their tops. Moorish-style architecture remained popular long after Muslim rule ended in Spain due to the Reconquista.

Many Christian Cathedrals were built in the Moorish architectural style. Jewish synagogues, like the Synagogue of El Tránsito in Toledo (built between 1357 and 1363), were also built in the Moorish style. The Spanish-Moorish artistic style shown by the Synagogue of El Tránsito became known as the Mudejar style. Overall, the architecture of al-Andalus shows the cultural exchange between Christian and Arabic architectural styles. The Arabic style also showed Muslim leaders' need to feel connected to their ancestral homelands.

Language and Literature

Just like art and architecture, language and literature in Al-Andalus developed through a blending process. It's also important to note that language and literature greatly influenced all areas of study.

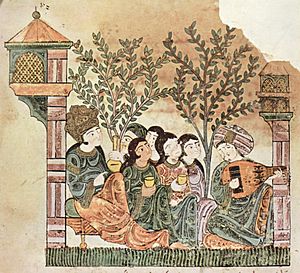

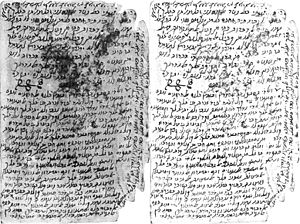

The Muslim invasion of Iberia brought about widespread education. This greatly increased the number of people who could read and write, compared to the rest of Christian Europe at the time. However, rural areas still had lower literacy rates. The literature of Al-Andalus shows a mix of Arabic, Christian, and Jewish styles. These styles blended over time under the Caliphate of Cordoba.

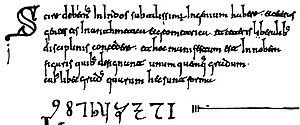

The Arabic literary tradition in Al-Andalus came from the Qur’an and Arabic poems. These poems often had both religious and everyday topics. Some poems contained love stories and secular themes that later influenced Iberian literature. By the 9th century, these poems became lyrical and almost musical. These musical poems were known as muwashshahs. Muslims also brought translations of ancient Greek and Roman works that had been lost during the Dark Ages. The Muslim invaders declared Arabic the official language of Al-Andalus. However, only a small number of people in the region actually used Arabic.

Different versions of Romance dialects (like early Spanish or Portuguese) continued to be spoken in many areas. These dialects varied from place to place with no clear borders. These Romance languages eventually mixed with Arabic and some Hebrew words. This created the Mozarabic dialect. This dialect became important in the literature produced in this area. Later, when Mozarabs spread across the Iberian peninsula, many words in modern-day Spanish, Portuguese, and Catalan came from these early Mozarabic Romance dialects. It's important to stress that there was no single standard language in the Iberian Peninsula or even in Al-Andalus when this style developed. This new Mozarabic style first appeared in literature in the kharjas or choruses of the muwashshahs.

These kharjas were usually written in Arabic or Hebrew. But eventually, they appeared in a common Mozarabic style. It was common for kharjas to mix phrases from Iberian local languages, Hebrew, and Arabic. Kharjas are very important to Iberian literature and language. They show a blend of Christian and Classical traditions (like having repeating choruses in lyric poems) with Hebrew and Arabic traditions (which focused on love and daily life struggles). This combination was important for language development. Local Romance languages began to adopt and change Arabic or Hebrew words found in the kharjas.

The growth of the Mozarabic style in language and literature led to what is called the Golden Age of Jewish culture in Spain. The exact dates for this golden age are debated. But it generally matches the start of the Caliphate of Cordoba, declined under Almoravid rule, and ended under Almohad rule. Jewish authors living in Al-Andalus were inspired by the new ideas that came with a wealth of literature. This literature included translations of classical Greek and Roman works under rulers like al-Hakam II, which Europeans had lost before the Muslim invasion. It also included new works that blended Christian and Arab ideas.

Muslim universities, libraries, courts, and to some extent Christian monasteries were centers for literature. The former were also centers for blending literature and ideas. Foreigners from across Europe and the Middle East came to these universities in Al-Andalus. They contributed their own ideas and translated many works from Al-Andalus when they returned home. Because of this exchange of literature, a lot of new works on theology, philosophy, science, and mathematics were created during this time.

The works of Jewish philosopher and theologian Maimonides, Muslim scholar Ibn Rushd (Averroes), Muslim doctor Abulcasis, and Jewish scholar and doctor Hasdai ibn Shaprut are direct results of this cultural exchange through literature. Their ideas are preserved in literature. For example, the novelist Ibn Tufail inspired John Locke’s theory of tabula rasa (the idea that the mind is a blank slate at birth), which had a huge impact. Both Jewish and Christian scholars chose Arabic as their language for academic writing. Jewish poet Moses ben Jacob ibn Ezra and Christian bishop Recemundus were both bilingual. Recemundus even wrote an Arabic-Christian religious calendar.

Literary development continued under the Almoravids. However, there was a gradual decline as Islamic laws were enforced more strictly. Under the Almohads, the progress of literature, which had started under the Caliphate of Cordoba, almost stopped. The Almohads censored works they thought went against the authority of the Qur’an. Scholars like Maimonides were treated harshly and forced to flee. The eventual removal of the Almohads, which happened because of the Christian Reconquista, saw a re-emergence of the literary works produced under the Caliphate of Cordoba. The Christian kingdoms of Iberia tried to keep this literary tradition alive. They translated many Arabic and Hebrew works into Latin and later into local languages (see Toledo School of Translators).

|

See also

In Spanish: Cristianos y judíos en Al-Ándalus para niños

In Spanish: Cristianos y judíos en Al-Ándalus para niños

|

|