Tirso de Olazábal, 1st Count of Arbelaiz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Most Excellent

The Count of Arbelaiz

|

|

|---|---|

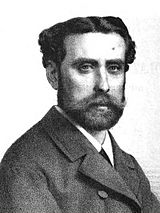

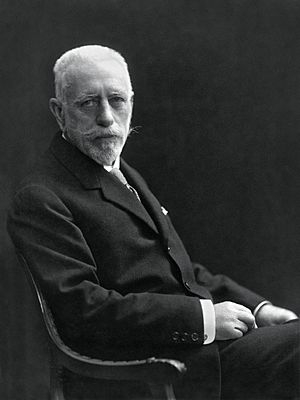

Formal photo portrait, 1921

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 January 1842 Arbelaiz Palace, Irun, Spain |

| Died | 25 November 1921 San Sebastián, Spain |

| Occupation | Politician |

Tirso de Olazábal y Lardizábal, 1st Count of Arbelaiz, 1st Count of Oria (born January 28, 1842 – died November 25, 1921), was a Spanish noble and Carlist politician. He was known for his important role in the Carlist movement, especially during the Third Carlist War. He helped get weapons and supplies for the Carlist army.

Contents

Family and Early Life

Family Roots

Tirso de Olazábal was born into a very old and important family from the Basque region of Spain. His family, the Olazábals, were among the first settlers in the province of Guipúzcoa. They were known for their bravery in battles and helped restore Spain with King Pelagius of Asturias. They also joined King Ferdinand the Saint in the Siege of Seville.

The Olazábal family was considered one of the most important families in Guipúzcoa. They owned a large area called Alzo and had control over the San Salvador Church there. Records from 1025 show that the Olazábal family owned 300 small villages, called caseríos, in Alzo.

Tirso's family history can be traced back to the 1300s. His great-grandfather, Domingo José de Olazábal y Aranzate, was the mayor of Irun in 1767 and 1778. Tirso's grandfather, José Joaquín Cecilio María de Olazábal y Murguía, served in the navy. His father, José Joaquín María Robustiano de Olazábal y Olaso, was elected to the Guipuzcoan government many times. He was also a famous cartographer, meaning he made maps. In 1836, he published a map of Guipúzcoa.

Tirso's mother was María Lorenza de Lardizábal y Otazu. Her father, Juan Antonio de Lardizábal y Altuna, was one of the biggest landowners in Guipúzcoa. He owned the Lardizábal palace in Segura. Tirso's maternal grandmother, María Benita Ruiz de Otazu y Valencegui, also came from important noble families. One of Tirso's great-great-grandfathers, Manuel Ignacio de Altuna y Portu, was a key figure in the Enlightenment in Spain. He was a scholar and a friend of the famous writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In 1748, he helped found the Royal Basque Society of Friends of the Country.

Growing Up

Tirso first went to school at a famous Jesuit college near Bordeaux, France. He studied philosophy there. Later, he studied mathematics in Paris. He loved music, especially Mozart. In the early 1860s, he started 18 local music bands in Guipúzcoa, bringing together musicians from all walks of life. In 1864, he won a gold medal at an art exhibition in Bayonne for directing an orchestra he created in Irun.

When his father died in 1865, Tirso inherited a lot of money and property. This included the beautiful Arbelaiz Palace in Irun, which had been in his family for centuries. Many famous historical figures had stayed at this palace, including kings and queens. The palace was named after the powerful Arbelaiz family who built it. It came to the Olazábal family through marriage in 1756.

He also inherited the Abaria Palace in Villafranca de Oria. This palace was important during the Third Carlist War because the Carlist leader, Carlos VII, stayed there.

Marriage and Children

In 1867, Tirso married Ramona Álvarez de Eulate y Moreda. She also came from a noble family with ties to Guipúzcoa and Navarre. Ramona's family included Juan Álvarez de Eulate y Ladrón de Cegama, who was a governor in New Mexico. Her father was a military man.

Tirso and Ramona had 11 children who survived childhood. Their oldest son, Ramón, married a woman related to the Portuguese royal family. They moved to Portugal. Two of their younger sons, Tirso and Rafael, were active in the Carlist movement for many years.

In 1934, Rafael de Olazábal met with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini to discuss support for their political movements in Spain. Later, Rafael supported Don Juan as the Carlist leader. Tirso's daughter, Vicenta de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, married Julio de Urquijo e Ibarra, a well-known Carlist and Basque activist. Many of Tirso's descendants became important figures in Spain and Portugal. The title of Count of Arbelaiz still exists today.

Early Political Life

Tirso Olazábal's political career began in 1865 when he was elected to the Guipuzcoan provincial government. He was very young and had no experience, so his election might have been a tribute to his late father. As a member, he welcomed Queen Isabel II during her visit to Tolosa. He was offered an important award but politely declined it.

In 1867, Olazábal was elected to the Spanish parliament, known as the Cortes. He was one of the youngest members. He was seen as a conservative and a supporter of the Catholic faith. In 1868, he again welcomed Queen Isabel II. He was saddened when she was removed from power during the Glorious Revolution later that year. In the 1869 elections, he ran on a platform of "God and traditional laws" and was re-elected. He was known for opposing the opening of casinos in San Sebastián.

Around 1869 or 1870, Olazábal became involved in the Carlist movement. The Carlists wanted a different royal family to rule Spain. He traveled to France to buy weapons for a planned uprising. In 1870, he bought 20,000 rifles in Antwerp and arranged for them to be shipped by sea.

He attended a big Carlist meeting called Junta de Vevey. Due to a misunderstanding, the weapons were not unloaded in Bilbao. Olazábal followed the ship to Genoa, Italy. He managed to trick the Italian police and get some weapons sent to Catalonia. Another shipment was stopped by the French, who thought it was a plot by Prussia. Olazábal went to Tours and spoke with Gambetta, a French politician, to get the weapons released. By this time, the Spanish government knew about his activities and started legal action against him.

The Civil War Years

When the Third Carlist War began, Olazábal was in Switzerland. He was appointed to help Doña Margarita, the Carlist leader's wife, to prevent her from being expelled from the country. He also acted as a link to Ramón Cabrera, another important Carlist general. Finally, he became the head of the "Arms Commission," which meant he was in charge of getting supplies for the Carlist army.

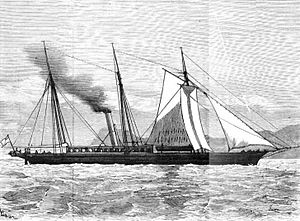

In early 1873, Olazábal bought 11,000 berdan rifles and 2 million cartridges in Versailles, France. These weapons were no longer useful for France. He arranged for two ships to transport the weapons to Spain. His plan was to send them to England first to trick the French. On July 13, 1873, the first shipment secretly reached the Ispaster beach in Spain. The same trick was used two weeks later at Cap Higuer. When another Carlist ship was stopped by a Liberal ship, Olazábal arranged for a new ship, the Orpheon, which successfully delivered weapons to Lequeitio, an area controlled by the Carlists. Two more missions were completed before the Orpheon sank in an accident.

Olazábal also organized a large fundraising effort. He arranged another delivery from France to England, but Spanish agents illegally seized the weapons in Newport. He sued them, and the Spanish embassy in London agreed to pay him a large amount of money, more than he had spent. In 1874, he bought a French ship, renamed it London, and used it to deliver artillery pieces to Bermeo. He also planned to send weapons to Catalonia, but the Carlists withdrew from that area. The London continued to deliver weapons until January 1876. Meanwhile, Olazábal arranged for 34 artillery pieces to be made in France and transported by land to the Carlist-controlled border in Irun. He was eventually forced to leave France because the Spanish government demanded it.

Because of his efforts, the Carlist artillery corps asked Carlos VII to make Olazábal an honorary colonel. Some historians say he provided more than half of all the artillery used by the Carlist troops. The Carlist leader recognized his work by giving him the title of Count of Arbeláiz. Olazábal's involvement in actual fighting was small. He is remembered for directing artillery fire from guns he had bought, aiming at Liberal troops from his family palace in Irun.

Quiet Years and Return to Politics

After the Carlists lost the war, Olazábal could not return to Spain. However, he was still very wealthy and was the highest taxpayer in Irun in the late 1870s. He moved to Saint-Jean-de-Luz in France, very close to the Spanish border. He bought several properties there, including a large home known as "Villa Arbelaiz" by the 1890s. French police watched him closely, believing he was still helping to coordinate Carlist activities and smuggle weapons. In 1877, the Carlist leader, Carlos VII, issued a statement promising to defend the traditional laws of the Basque region. At this time, the Madrid newspapers called Olazábal "famous Tirso de Olazábal."

When it became clear that the war would not restart, Olazábal became less active in politics. He contributed money to a monument for a Carlist hero, Zumalacarregui, and sent congratulatory letters to a pro-Carlist newspaper. In the mid-1880s, he started sending short news notes from Saint-Jean-de-Luz to the newspaper.

In 1887, the Carlist leader in Guipúzcoa resigned, and Carlos VII appointed Olazábal as his replacement. This was a surprising choice since Olazábal lived outside Spain. He immediately had disagreements with other Carlist leaders about how local officials should be chosen. In 1888, a group called the Integrists broke away from the Carlist movement. Even though Olazábal had been linked to some of their ideas, he remained loyal to Carlos VII. He became one of the most important politicians in the Carlist party after this split.

In 1889, Olazábal was invited to the wedding of Carlos VII's daughter, Blanca de Borbón. Even the Liberal newspapers still saw him as a dangerous exile. His home in Saint-Jean-de-Luz became a meeting place for Carlists living outside Spain. He got along well with the new Carlist leader, Marqués de Cerralbo.

Election Years

Under the leadership of de Cerralbo, the Carlist movement decided to participate in the Cortes elections for the first time in 1891. Olazábal was against this idea, fearing the Carlists might not do well. However, he was given an important task: to defeat Ramón Nocedal, the leader of the Integrist rebels, in the Azpeitia district of Guipúzcoa. Carlos VII desperately wanted Nocedal to lose. The Carlists put a lot of effort into the campaign, holding banquets and praising Olazábal. But Nocedal won, which was a big disappointment for the Carlists. Olazábal blamed the church and the Jesuits for favoring the Integrists.

Two years later, in the 1893 campaign, local Integrists suggested forming a united front in Guipúzcoa. Olazábal was open to the idea, but he refused to let them have the Azpeitia district. He faced Nocedal again and lost by only 17 votes. It took some time and political talks before Olazábal was officially declared defeated in 1894.

Even though Olazábal's standing with the Carlist leader might have lessened, he was still highly respected. In 1894, when Don Jaime, the 24-year-old son of the Carlist leader, was to visit Spain for the first time, Olazábal was chosen as his guide. The trip lasted 37 days and covered many cities across Spain. It became a huge media event, talked about for months. Olazábal became quite famous. In 1895, he published a book about the trip.

Before the 1896 elections, Olazábal said he only wanted to get healthy again. However, he soon claimed that the Jesuits in Azpeitia had finally recognized Carlos VII's authority. Nocedal was defeated, but by another Carlist candidate. Olazábal ran for the Senate and was elected from Guipúzcoa. He would have been part of a small group in the Senate, but he refused to swear loyalty to King Alfonso XIII. So, his election was more about prestige.

La Octubrada (The October Uprising)

In September 1896, Olazábal went to Madrid and signed a statement from the Carlist groups in parliament. This statement followed the Carlists leaving parliament and was part of their 1897 program. Both documents said the Carlists would not fight, but they found the current government system unacceptable.

The 1896 statement also mentioned problems overseas. When the conflict turned into the war with the United States, Olazábal declared that Carlists would not cause trouble. Their main goal was to keep Spain united. However, the government watched him closely. In July 1898, his home in Saint-Jean-de-Luz was again reported as a Carlist operations center. Despite his denials, rumors spread about Carlist war preparations. At this time, Olazábal was raising money from the same sources he had used 30 years earlier. Carlist leaders suggested he should control all party funds and foreign activities.

In early 1899, Olazábal was busy smuggling weapons. He bought 53,000 Gras rifles and had them changed to fit Spanish cartridges. He used his network of smugglers to bring some across the Pyrenees mountains. There were also plans to use Cap Higuer as a landing point for weapons from the sea. Amidst all this, Olazábal also helped plan Carlist election alliances in Guipúzcoa for the 1899 elections. When the leader de Cerralbo was rumored to resign, the press thought Olazábal might replace him.

French police reported that weapons were being bought in London, Brussels, Paris, and Switzerland. In early 1900, Olazábal delivered 300 rifles from Bayonne across the Pyrenees. The French government then gave in to pressure from Spain and ordered him to move north of the Loire river. Olazábal moved to Paris but appealed the decision. The Spanish embassy wanted him to stay away, but then decided he would be easier to watch in Saint-Jean-Jean-de-Luz. In October, the embassy changed its mind again and demanded Olazábal be held in custody. Although the French did hold other Carlist plotters, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Delcassé, thought it was too harsh to do this to someone who had lived there legally for a long time. The Spanish government backed down to avoid a diplomatic problem.

When small Carlist uprisings happened in Catalonia in October 1900, Olazábal and other Carlist leaders were in Paris. They claimed to be completely surprised. It's unclear if they truly were. While Olazábal helped with weapons and hoped for support from Spanish generals, historians believe the rebels acted on their own, perhaps even against official orders. Some people thought the uprisings were meant to cause problems in the Madrid stock market.

Early 1900s: A New King

In the early 1900s, Olazábal was less active. He mostly attended occasional meetings with other Carlist leaders at his home in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. His home, Villa Arbelaiz, became a social hub. It welcomed close friends, family, and important people connected to the Carlist movement. Among the regular visitors were Don Jaime de Borbón, the former Queen Natalie of Serbia, and other European nobles and Carlist politicians.

During these years, Tirso and his family stayed close to Carlos VII's family. They often visited them in Venice. In 1905, Tirso traveled to Spain again, accompanying Don Jaime during a visit. He continued to give news about the royal family to the press. However, by 1907, his son Rafael was often the one accompanying Don Jaime. It seems his sons were starting to take over some of his duties. Tirso exchanged many letters with other Carlist leaders. When the Carlist leader Matías Barrio died in 1909, the press often mentioned Olazábal as a possible successor.

Olazábal was a major Carlist figure at the funeral of Carlos VII in Varese in July 1909. When there was unrest in Catalonia later that year, he resumed his role of smuggling weapons for the new Carlist leader, Jaime III. French security believed the Carlists were involved in a large smuggling operation, controlled by a team in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. The French prime minister estimated that thousands of rifles were smuggled between December 1909 and February 1910. Historians think the weapons came mostly from England, with some from Belgium, France, and Austro-Hungary. They were disguised as farm equipment, railway parts, or even pianos. After passing Spanish border guards, they were stored in various towns.

Madrid demanded that the French closely watch Olazábal and his son-in-law, Julio de Urquijo e Ibarra. Because Paris was upset with Olazábal's public criticism of their education system, he was ordered to move north of the Loire river again in October 1910. His duties were taken over by Urquijo, who was allowed to stay in the south. Olazábal was allowed to return to Labourd in May 1911, though some sources say he was expelled from France in 1912. By this time, any idea of another Carlist uprising was long gone.

Final Years

In 1910, during a crisis over a new law, Olazábal became a Carlist representative in a national Catholic alliance. He joined a Catholic defense group in Biscay, not Guipúzcoa.

At this time, Juan Vázquez de Mella was becoming the most important Carlist figure. He planned to replace the current Carlist leader, Bartolomé Feliu, with his friend, the aging Marqués de Cerralbo. Olazábal supported this plan. In 1911, he wrote a letter to Jaime III, suggesting that de Cerralbo be named the new political leader. In 1912, the Carlist leader partly agreed by creating a group to help Feliu. Within this group, Olazábal was confirmed as the leader for all of Vascongadas and La Rioja, which was a step up from his previous role. In early 1913, with Feliu removed, Olazábal was made a member of the electoral commission under de Cerralbo's leadership. However, his time in this role was short. In July 1913, he resigned from all his Carlist positions and announced he was leaving politics.

There is little information about Olazábal's public activities in his very last years. It's not clear if he retired due to his age or political disagreements. He was still seen as a respected figure within Carlism. In 1919, a major conflict happened within the Carlist movement between de Mella and Jaime III. This led to a group called the Mellistas breaking away. Olazábal supported the rebels. Since he was already retired from official duties, his support was mostly symbolic. It is still unclear why, after almost 50 years of loyal service, Olazábal decided to abandon his king.

Legacy as Guipuzcoan Leader

Olazábal led the Carlist movement in Guipúzcoa between 1887 and 1908. This was a time of big changes in the province. Some historians believe his leadership style greatly affected the future of Carlism in the Basque region.

Even though he lived outside the province, Olazábal often managed Carlist affairs in Guipúzcoa by himself. He was supposed to be helped by a provincial council, but he never actually gathered this group. When the Carlist leader de Cerralbo tried to build strong party structures across the country, Guipúzcoa was one of the slowest provinces to develop. Olazábal did not like modern ways of political organizing. He thought that de Cerralbo's grand trips only led to Carlist supporters being arrested.

Olazábal's approach to rebellious Carlist groups in Guipúzcoa was mixed. On one hand, he insisted on complete loyalty to the king. He expelled those suspected of siding with the rebellious Nocedal in 1888–1889 and later removed Victor Pradera and his allies in 1910. On the other hand, he was flexible about forming election alliances with the Integrists. An agreement in Guipúzcoa in 1898 ended a decade of hostility and inspired cooperation in other provinces. In terms of political strength, Guipúzcoa was second only to Navarre in the number of parliamentary seats won by Carlists during Olazábal's time. This showed that the province remained a strong Carlist area.

Olazábal started his political life supporting "God and traditional laws." He also protested to Carlist leaders about breaking with Basque traditions. However, he is not known for being especially focused on regional rights. Some people at the time described him as not caring much about traditional laws. One historian says that until the early 1880s, Carlism in Guipúzcoa had a clear Catholic and traditional Basque focus. Later, due to the provincial leaders, the movement became stuck. It failed to adapt to the rising Basque national movement. Olazábal was related to José Ignacio Arana, but he probably did not understand the changes happening when Daniel Irujo resigned in 1908. He understood even less about the Basque workers' movement, which he strongly opposed, like during a gathering in Eibar in 1912 that ended in riots.

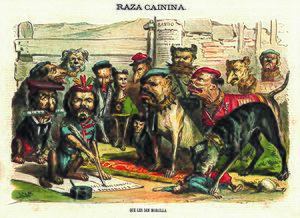

In Literature

Tirso de Olazábal appears in the Fifth Series of Benito Pérez Galdós's famous novels, Episodios Nacionales.

It is also possible that Olazábal is featured in the 1919 novel The Arrow of Gold by Joseph Conrad. The novel includes a character called "Lord X," whose activities as a weapons smuggler are similar to Olazábal's.

Children

Tirso married Ramona Álvarez de Eulate y Moreda in 1867. She came from a noble family connected to Guipúzcoa and Navarre. They had twelve children, and eleven of them lived past infancy:

- Mercedes de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who never married.

- Margarita de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who never married.

- Ramón de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who married Maria Luísa de Mendóça Rolim de Moura Barreto in 1899. She was related to the Portuguese royal family. They had six sons and four daughters.

- José Joaquín de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate.

- Tirso de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who married María de la Concepción de Jaraquemada y Quiñones in 1916. They had no children.

- Vicenta de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who married Julio de Urquijo e Ibarra, Count of Urquijo in 1894. They had no children.

- Lorenza de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who became a nun.

- Blanca de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who also became a nun.

- Rafael de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who married Ana Yohn y Zayas. They had four sons and four daughters.

- Ignacio de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who married Ana Vives y Rámila, a Chilean heiress, in 1918. They had one daughter.

- Pelayo de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who married María Isabel Ruiz de Arana y Fontagud in 1928. She was the 12th Countess of Cantillana. They had two sons and five daughters.

- Roberto de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate, who died as a child.

Images for kids

-

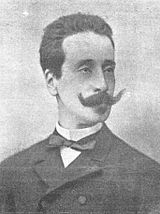

Olazábal with his king and Carlist leaders in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, ca 1910

See also

In Spanish: Tirso de Olazábal para niños

In Spanish: Tirso de Olazábal para niños