Toronto ravine system facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Toronto ravine system |

|

|---|---|

Little Rouge Creek and the Rouge Valley, one of the ravines in the system

|

|

| Location | Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Area | 110 square kilometres (42 sq mi) |

| Formed by | Erosion, receding glaciers |

The Toronto ravine system is a special part of the city's landscape. It is a huge network of deep ravines that form a large urban forest. This forest runs through most of Toronto. It is the biggest ravine system in any city in the world. About 110 square kilometres (42 sq mi) of land, both public and private, is protected by a special rule called the Ravine and Natural Feature Protection Bylaw. Because of its size, Toronto is often called "a city within a park."

The ravine system started forming about 12,000 years ago. This was when the huge glaciers that covered Toronto began to melt and move away. They left behind rivers and valleys. Because of the steep hills and valleys, not many buildings were built in the ravines until the mid-1800s. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, some changes and new buildings were made. However, after Hurricane Hazel hit Toronto in 1954, most big building projects in the ravines stopped. The destruction from the hurricane showed how dangerous it was to build in these areas.

Today, most of the Toronto ravine system is still natural. Much of its public land is now protected as parkland. Even though it's mostly undeveloped, the city uses the ravines to help manage floods and clean the air. People also use them for fun outdoor activities. The ravines are also home to many animals and plants. They act as a wildlife corridor, helping animals move safely through the city.

Contents

How Toronto's Ravines Were Formed

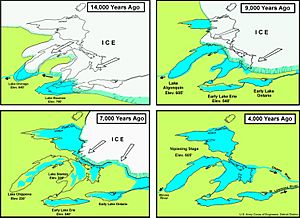

The Toronto ravine system began about 12,000 years ago. This was at the end of the last Ice Age. Rivers and valleys formed as the giant glaciers moved away, leaving behind changed land. Melted ice from the Oak Ridges Moraine, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) north of Toronto, flowed southeast. This water went towards an ancient lake called Glacial Lake Iroquois. It carved through almost 100 metres (330 ft) of soft soil, sand, gravel, and clay. This carving created the deep ravine valleys we see today.

Most of the meltwater flowed southeast into the ancient lake. This created small ponds north of Toronto. However, the early Don and Humber rivers were different. They flowed along old paths of an even older river system. This ancient system was buried during the last Ice Age.

About 9,000 years ago, the glaciers had moved north of the St. Lawrence Valley. The water level of Glacial Lake Iroquois then started to drop. As the water levels went down, new waterways formed. The water flowed through the old lakebed into a new lake called Lake Admiralty. The two main parts of the Don River joined at the old shoreline of Lake Iroquois. New streams also appeared.

This new lake existed until about 8,000 years ago. Then, the land around Quebec and northeastern Ontario began to rise up. This happened because the heavy weight of the glaciers was gone. As the land near the lake's outlet to the St. Lawrence River rose, water levels in the lake slowly went up. During this time, large flat areas in the ravine system, like the lower Don Valley, were formed. This happened as rising water from Lake Ontario pushed into the lower valley. Sediment from the upper valley also built up in the lower water. The flooding of the lower ravines also created several sand bars, lagoons (ponds), and wetlands (marshy areas) near Toronto's shoreline.

How People Changed the Ravines

Before European settlers arrived, the land from Lake Ontario to the Oak Ridge Moraine was covered in forests. These forests had maple, beech, and hemlock trees. Low-lying areas had forests and swamps, with large marshes along the Toronto shoreline. In the early 1800s, many trees around the Town of York (now Toronto) were cut down. This included trees in the ravine system. However, some parts of the ravines saw very little building. This was because flood-prone areas were not good for urban development. Because of this, the ravine system still has the most trees in the city that are older than European settlement.

The ravines changed the most because of human activity in the 1800s and early 1900s. Several natural valleys were filled in. Rivers were changed or even buried completely. Wet areas were drained to make way for new buildings. The Don River was changed near its mouth. A concrete channel was built to stop the Port Lands from flooding. Creeks and ravines in downtown Toronto were also buried. These included Garrison and Taddle Creek.

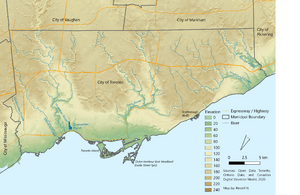

By the mid-1900s, the Don River and a small part of Taddle Creek were the only waterways left flowing into Toronto Bay. The remaining parts of Toronto's ravine system are mostly around four main waterways: the Don River, Highland Creek, Humber River, and the Rouge River. Smaller ravines can also be found along other waterways of Toronto, like Etobicoke Creek and Mimico Creek.

Where Toronto's Ravines Are Found

The ravine system is on the north shore of Lake Ontario. It sits between the Carolinian forest and the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands. The ravines include large river valleys and smaller creeks. Many of the bigger waterways have narrow, steep-sided valleys. The water has worn away the soft ground, showing old Ordovician rocks. Many of these rocks can be seen along the stream banks. The ravine system is part of a larger network of ravines that goes up to the Oak Ridges Moraine, north of Toronto. The biggest ravines are around the rivers that flow south from the moraine to Lake Ontario: the Don, Humber, and Rouge rivers.

Today, the ravine system is protected by the Ravine and Natural Feature Protection Bylaw. This rule says a ravine is a distinct landform. It must have at least 2 metres (6.6 ft) difference in height between its highest and lowest points. It also needs to have plants growing on it, and water must flow through or near it, or have done so in the past. This law also protects areas around the ravines and other important natural spots. In total, it protects about 17 percent of the city's land, which is about 11,000 hectares (27,000 acres). The system has at least 150 ravines, making it the largest in any city in the world. The edges of the ravine system add up to over 1,200 kilometres (750 mi). This is ten times longer than Toronto's waterfront. The ravines are mostly surrounded by homes.

About 60 percent of the protected land is owned by the public. The other 40 percent is privately owned. In this area, there are 86 "Environmentally Significant Areas" recognized by the city. There are also 1,500 urban parks. Most of the ravine system stays natural to help control floods. This is because the water levels in the rivers and streams can change a lot. In late summer, many small streams might slow down or even dry up. But in spring and after big storms, creeks in the ravines often overflow their banks. More than two-thirds of the public parts of the ravine system are forests. The rest are beaches, meadows, open water, new growth areas, and wetlands. The ravine system makes up about 36 percent of all the tree cover in the city.

Almost the entire ravine system is part of the city's green space and natural heritage. City rules mostly stop building in these areas. The only exceptions are for parks, cultural places, and important public works. Rules that limit building in the ravines include the Ravine and Natural Feature Protection Bylaw. This rule stops people from cutting down trees in the system without a permit. Another rule, TRCA Regulation 166/06, stops any human changes or filling of the ravine system's waterways or wetlands without a permit from the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA).

Waterways of the Ravine System

The Toronto ravine system is part of a bigger watershed system. This system includes the Greater Toronto Greenbelt and the Oak Ridges Moraine. The ravine system has seven watersheds: the Don River, Etobicoke Creek, Highland Creek, Humber River, Mimico Creek, Petticoat Creek, and the Rouge River. In total, about 371 kilometres (231 mi) of waterways flow through the city and its ravines. Most of the smaller creeks and streams are within Toronto's city limits. However, the three largest rivers (Don, Humber, and Rouge) start at the Oak Ridges Moraine, north of the city.

Many of the ravine systems around these waterways branch off into smaller ravines. These wind through business, industrial, and residential areas of the city. The shape of streams in the ravines is always changing. Big storms can cause flooding and erosion on river banks. Waterways in narrow ravines, or those that have been straightened, are especially likely to change due to erosion. The Humber watershed is the largest of the seven. However, the Don watershed covers the biggest part of the city's land area, making up 32.5 percent. The point where the Humber, Don, and Rouge River watersheds meet is near Bathurst Street and Jefferson Sideroad, at the Vaughan-Richmond Hill border.

Because of a lot of building around Black Creek, its water quality is much lower than other watersheds in the ravine system.

Animals and Plants in the Ravines

The ravine system has the most different kinds of ecosystems, species, and genetic variety in the city. This is because it has many different habitats, like forests, wetlands, rivers, and streams. These connected habitats help support the wide range of life in the ravines. The ravine system is home to about 1,700 species of animals and plants. This includes many species that are rare or at risk locally, regionally, and provincially. About 90 percent of animals that live in Toronto make their home in the ravine system.

Besides providing a home in the city, the ravine system also acts as a wildlife corridor. This allows animals to travel safely from one part of the city to another. These corridors are very important for wild mammals. They are the only safe way for these animals to move around to find new mates and create their own homes.

The ravine system is one of the northernmost Carolinian forests in North America. It has mixed woodlands and some traces of the boreal forest from further north. About 1,000 plant species can be found in the ravine system. This is about 25 percent of all plant species found in Ontario. Most native plants, like the oak, have strong genes. This makes them better able to handle extreme weather and pests. Poison ivy and nettles are also common.

However, the quality of the plants has gone down between 2009 and 2019. This is because invasive plant species are spreading throughout the ravines. At least one of 15 high-risk invasive plant species was found in 75 percent of the areas studied. Norway Maples are an invasive tree species found in the ravine system. They are taking over and harming native plants. A study in 2018 showed that native plants in the ravine system could disappear if nothing was done about the invasive plants. Invasive plants like Norway maple had taken over large parts of the ravines by killing off smaller native plants and young trees.

Human History and the Ravines

Many old tools and items from the Archaic period have been found in the ravine system. After corn was brought to southern Ontario around 500 CE, the ancestral Wyandot people started growing it. They cleared the flat areas near rivers for their crops. By the 1300s, there were many Wyandot and Petun communities around the Don, Humber, and Rouge rivers. They usually cut down trees from nearby cedar swamps to build their homes. By the late 1500s, most of these communities had moved north. These areas were later used by the Seneca in the 1600s. Early European explorers saw a Seneca village on the Humber and another on the Rouge rivers in the 1660s.

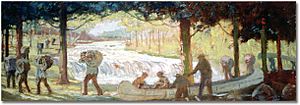

The first Europeans in the area were explorers, fur traders, and missionaries. A French mission was set up at the mouth of the Rouge River by 1669. From the 1600s to the 1800s, the ravine system was part of the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail. This was an important route for fur traders using canoes and portages to reach the upper Great Lakes.

The first sawmill in Toronto opened in the Don River valley in 1795. In the late 1700s and 1800s, parts of the ravine system were logged for building materials. This left few trees in Toronto that are older than 1850. From the late 1700s to the 1900s, clay was also dug out of the ravines. The first brickworks opened in the ravine system in 1796. The Don Valley Brick Works was a big brickworks. It was a major source of building material for the city until 1984. Clay dug from the Don Valley Brick Works has given scientists the best record of an ancient warm period in northern North America.

Building in the ravines was limited in the early 1800s. The muddy glacial soil in the valleys made construction very difficult. However, the cleared parts of the ravine system became sites for dumps, farms, mills, and landscaped parks in the 1800s and 1900s. By the mid-1800s, the Don Valley was seen as a place for "undesirables." City residents thought the ravine was an area that encouraged lawlessness. This view led builders to create less desirable neighborhoods near the ravines. These areas were on the edge of 19th-century Toronto and close to its industrial lands.

In the late 1800s, many wet areas and ponds at the mouth of the Don River were filled in. This was because the shallow Ashbridge's Marsh was good for new development as the Port Lands. The Don River near its mouth was also straightened. This was done to attract ships further upriver. Some smaller waterways in Toronto were also buried during this time. This happened after public health officials asked the city to cover these smaller waterways. People were using them to dump trash and human waste. The city's sewage system and water filtration plant were also built into the ravine system in the late 1800s. Many of Toronto's storm drains still empty into the ravines. Large parts of the city's infrastructure still rely on the ravine system to absorb and filter storm water when there is too much rain.

By the mid-1950s, there were plans to create public parks in the ravine system. There were also plans to protect the system from more building. Building in the ravine system mostly stopped after Hurricane Hazel passed through Toronto in 1954. The hurricane destroyed many homes and left 1,868 families without a place to live. Many of the destroyed homes were in the changed rivers and streams of the ravine system. These areas were already at risk of flooding from heavy rains. The TRCA was formed because of this disaster. No large-scale building has happened in the ravine system since the TRCA was created. Their flood control and water management rules prevent further development. Most of the remaining ravine system was kept natural. The building of the Don Valley Parkway was the only major exception. This highway was planned in 1954 and finished in 1961.

The city government went ahead with its plan to create several parks in the ravine system. These parks were built further upstream, next to the TRCA's protected areas. Efforts to bring the ravine system back to its natural state started in the 1990s. Groups like the Task Force to Bring Back the Don were formed. They helped with tree planting and creating new wetlands.

Ravines in the 21st Century

In 2002, the municipal government of Toronto passed a law to officially protect the ravine system from human development.

In the 2000s, illegal dumping of garbage in the ravines became a problem for city forestry officials.

A report in 2018 estimated that the ravine system provided the city with C$822 million in "eco-system services" in 2017. These services include making the city beautiful, cleaning the air (carbon sequestration), helping with floods, controlling temperature and noise, and providing places for fun. The report estimated that the ravine system removes 14,542 tonnes of carbon from the air each year.

Work on new tunnels to catch combined sewer overflows started in December 2019. These tunnels will stop dirty water from flowing into the Don River and Lake Ontario. Instead, they will send the overflow to a treatment plant for cleaning.

Fun Activities in the Ravines

The city government's official ravine plan says that the ravine system should stay in its natural state. Because of this, fun activities in the ravines are limited to quiet ones. These include cycling, hiking, and cross-country skiing in the ravine's parks and on its trails. There are about 1,500 urban parks within the ravine system. However, access to some ravine parks is only for people walking. This is especially true for parks where the path to the sidewalk or road is very steep (more than 45 percent slope).

Besides small local parks, larger urban parks that cover big parts of the ravine system have also been created since 2010. In 2011, the federal government announced it would create a national park around the Rouge River. To make this park, land was given from the city of Toronto and nearby towns to Parks Canada. Rouge National Urban Park was officially opened on May 15, 2015. As of July 2019, the park includes 95 percent of the 79.1 square kilometres (30.5 sq mi) of land promised by the city, province, and federal governments. Don River Valley Park is another large park in the ravine system opened by the city. This park covers over 200 hectares (490 acres) of the lower Don River valley. Its creation was part of a bigger plan to restore the area naturally.

In 2017, the city put up new signs on the trails. These signs give information about the area. They were first put on the trails of the lower Don River. In 2017, 924,486 hikers and 398,240 cyclists used the trails in the Toronto ravine system. The heavy use of some trails is a problem for conservation efforts. These trails show signs of faster erosion and can disturb wildlife.

The Ravines in Books and Art

Toronto's ravines are often seen as a key part of the city's "city within a park" feeling. Architect Larry Richards says Toronto is like San Francisco "turned upside down." This is because San Francisco has many hills, while Toronto has deep ravines. Sandy M. Smith, a professor of urban forestry, says the ravine system acts as the "green veins of the city." She notes that they shape the city's landscape and road network, as roads have to follow the ravine's edges. Anne Michaels also calls Toronto a "city of ravines" in her book Fugitive Pieces. She describes the ravine system as a place where you can "traverse the city beneath the streets, look up to the floating neighbourhoods, houses built in the treetops." In many books, like Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle, the ravine system is shown as a meeting place. It's where the wild, dense nature meets the neat streets of suburban Toronto. The unique shape of Toronto was one of the main reasons Atom Egoyan chose to set his film Chloe in the city.

The importance of the ravine system to the city's character has influenced many Toronto artists and authors. Robert Fulford said that the "ravines are the chief characteristic of the local terrain, its topographical signature." He added that they are both a real (though often hidden) part of our surroundings and a strong force in our city's imagination. He called them the "shared subconscious of the municipality, the place where much of our literature is born." Fulford also commented that the ravine system was often a Torontonian's first look at wilderness. For many, it represented a "savage foreign place" and a "republic of childhood." Parents warned younger children about "evils" there, while older kids saw the ravines as the only place to "find freedom from the vigilant gaze of adults." Fulford suggested that childhood experiences with the ravines led Toronto authors to use them as "receptacles of the childhood experiences that they have repressed." He also saw them as a "creative, liminal space in which the ambiguities of life can play out."

Other artists and authors who have featured the Toronto ravine system in their works include Morley Callaghan, Douglas Anthony Cooper, Ernest Hemingway, Doris McCarthy, and Michael Ondaatje.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |