Tunisian Arabic facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tunisian Arabic |

|

|---|---|

| تونسي Tounsi | |

|

|

| Pronunciation | [ˈtuːnsi] |

| Native to | Tunisia, north-eastern Algeria, Tripolitania |

| Ethnicity | Tunisian Arabs |

| Native speakers | 12 million (2008-2020 census)e25 |

| Language family |

Afro-Asiatic

|

| Writing system | Arabic script, Latin script |

| Recognised minority language in | As a variety of Maghrebi Arabic on 7 May 1999 (Not ratified due to several Constitutional Matters): |

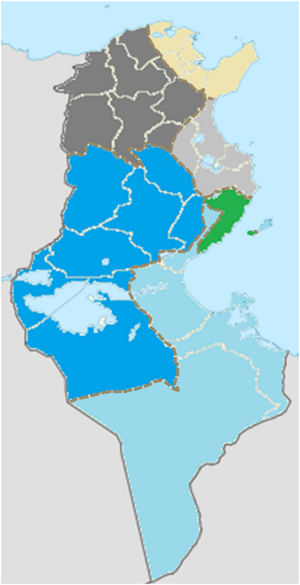

Extent of Tunisian Arabic

|

|

Tunisian Arabic, often just called Tunisian, is a type of Arabic spoken in Tunisia. More than 11 million people speak it. Tunisians call it Tounsi or Derja, which means "Everyday Language". This helps tell it apart from Modern Standard Arabic, which is the official language of Tunisia. Tunisian Arabic is quite similar to the Arabic spoken in eastern Algeria and western Libya.

Tunisian Arabic blends into Algerian Arabic and Libyan Arabic near the borders of Tunisia. Like other Maghrebi Arabic types, its words mostly come from Semitic Arabic. It also has some words from Berber, Latin, and maybe even Neo-Punic. About 8% to 9% of its words are from Berber. Plus, Tunisian Arabic has borrowed words from French, Turkish, Italian, and languages from Spain.

Many Tunisians, both in Tunisia and living abroad, often mix languages when they speak. They might switch between Tunisian, French, English, or Standard Arabic in their daily talks. Because of this, Tunisian Arabic has taken in new French and English words, especially for technical topics. Sometimes, older French and Italian words have been replaced by Standard Arabic words. Even educated people mix Tunisian Arabic with Modern Standard Arabic. This mixing has not stopped new French and English words from being used in Tunisian.

Tunisian Arabic is also closely related to the Maltese language. Maltese developed from Tunisian and Siculo-Arabic. People speaking Maltese and Tunisian Arabic can understand about 30% to 40% of what each other says.

Contents

- What Kind of Language is Tunisian Arabic?

- How Did Tunisian Arabic Develop?

- Special Features of Tunisian Arabic

- Tunisian Arabic Dialects

- Where is Tunisian Arabic Used?

- How Tunisian Arabic is Written

- Tunisian Arabic Vocabulary

- How Tunisian Arabic Sounds

- How Words are Formed (Morphology)

- Meanings and How Language is Used

- International Influences

- See also

What Kind of Language is Tunisian Arabic?

Tunisian Arabic is one of the many Arabic languages. It belongs to the Semitic group, which is part of the larger Afroasiatic language family. It is a type of Maghrebi Arabic, like the Arabic spoken in Morocco and Algeria. Speakers of Modern Standard Arabic or Arabic from the Middle East often find Maghrebi Arabic hard to understand.

Tunisian Arabic has many older dialects. But its main form is mostly a Hilalian variety of Maghrebi Arabic. This is because of the Banu Hilal people who moved there in the 11th century. This migration also affected other Maghrebi Arabic types.

Because Arabic is a dialect continuum (meaning dialects blend into each other), Tunisian Arabic is partly understood by speakers of Algerian Arabic, Libyan Arabic, Moroccan Arabic, and Maltese. However, it is only slightly understood, if at all, by speakers of Egyptian, Levantine, Mesopotamian, or Gulf Arabic.

How Did Tunisian Arabic Develop?

The Early Days of the Dialect

Languages in Ancient Tunisia

In ancient times, people in Tunisia spoke Berber languages. These were similar to the Numidian language. However, these languages slowly became less common after the 12th century BC. Their use was mostly limited to the western parts of the country.

Around the 12th to 2nd century BC, people from Phoenicia settled in Tunisia. They founded ancient Carthage and mixed with the local people. These migrants brought their culture and language, which spread from Tunisia's coast to other coastal areas of Northwest Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Mediterranean islands. By the 8th century BC, most people in Tunisia spoke the Punic language. This was a form of Phoenician language influenced by the local Numidian language. Even then, the Berber language used near Punic settlements changed a lot. In cities like Dougga and Bulla Regia, Berber lost its sound system but kept most of its words. The word "Africa", which names the continent, might come from the Berber tribe called the Afri. They were among the first to interact with Carthage. Also, the Tifinagh alphabet developed from the Phoenician alphabet during this time.

After the Romans took over Carthage in 146 BC, people along the coast mainly spoke Punic. But this influence lessened further from the coast. From the Roman period until the Arab conquest, Latin, Greek, and Numidian further shaped the language. This new version was called Neo-Punic. This also led to African Romance, a Latin dialect influenced by other languages in Tunisia. Punic likely survived the Arab conquest of the Maghreb. An 11th-century geographer, al-Bakri, wrote about people in rural Ifriqiya speaking a language that was not Berber, Latin, or Coptic. This suggests spoken Punic lasted long after its written use. Punic and Arabic are both Semitic languages, sharing many common roots. This might have helped Arabic spread in the region.

The Middle Ages

Classical Arabic became the language for government and administration in Tunisia, then called Ifriqiya, starting in 673 during the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb. People in many cities slowly adopted Arabic. By the 11th century, local languages like African Romance and Berber mixed with Classical Arabic. This created new urban dialects in Tunisia's main coastal cities. These dialects were slightly influenced by common Berber language features and words, like how they form negatives. They were also shaped by other historical languages.

Many Tunisian and Maghrebi words, like qarnīṭ ("octopus"), come from Latin. These dialects were later called Pre-Hilalian Arabic dialects. They were used alongside Classical Arabic for communication in Tunisia. Also, Siculo-Arabic was spoken on islands near Tunisia, like Sicily, Pantelleria, and Malta. It interacted with Tunisian dialects. This made the grammar and structure of these dialects more different from Classical Arabic.

By the mid-11th century, the Banu Hilal people moved to northern and central Tunisia. The Banu Sulaym moved to southern Tunisia. These groups played a big part in spreading Tunisian Arabic across much of the country. They also brought features from their own Arabic dialects. For example, people in central and western Tunisian Arabic began using the sound [ɡ] instead of [q] in words like qāl "he said". Some linguists believe that even the change of sounds like /aw/ and /aj/ to /uː/ and /iː/ came from the Hilalian influence. Also, the way new towns spoke Tunisian Arabic was shaped by the sounds of these immigrants. The Sulaym even spread a new dialect in southern Tunisia, which became Libyan Arabic.

However, some dialects were not as affected by the Hilalian influence. These include Judeo-Tunisian Arabic, spoken by Tunisian Jews, which kept foreign sounds in borrowed words and was slightly influenced by Hebrew sounds. The Sfax dialect and the traditional Tunisian urban women's dialect also avoided much of this influence.

By the 15th century, after the Reconquista and the decline of Arabic-speaking al-Andalus, many Andalusians moved to Tunisia's main coastal cities. These migrants brought features of Andalusian Arabic to the city dialects in Tunisia. For example, they brought back the sound [q] instead of the nomadic Hilalian [ɡ]. They also simplified speech, making the language even more different from Classical Arabic. The scholar ibn Khaldun noted these changes in his book Muqaddimah in 1377. He said that mixing Classical Arabic with local languages created many Arabic varieties that were very different from formal Arabic.

The Ottoman Period

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, Tunisia was ruled by Spain and then the Ottoman Empire. It also welcomed Morisco and Italian immigrants starting in 1609. This connected Tunisian, Spanish, Italian, Mediterranean Lingua Franca, and Turkish. Tunisian gained new words from Italian, Spanish, and Turkish. It even adopted some structures, like the -jī suffix added to words to mean professions, such as kawwāṛjī (football player) and qahwājī (coffee seller). In the mid-19th century, European scientists began studying Tunisian Arabic. In 1893, the German linguist Hans Stumme completed the first language study. This started a research trend on Tunisian Arabic that continues today.

Modern History

During the French protectorate of Tunisia, French greatly influenced Tunisian Arabic. New words, meanings, and structures came from French. This made Tunisian even harder for Middle Eastern Arabic speakers to understand.

However, this period also saw a rise in interest in Tunisian Arabic. It began to be used formally by groups like Taht Essour. More research was done, mainly by French and German linguists. Tunisian Arabic was even taught as an optional language in French high schools.

By Tunisia's independence in 1956, Tunisian Arabic was mainly spoken in coastal areas. Other regions spoke Algerian Arabic, Libyan Arabic, or various Berber dialects. This variety came from many factors: the country's long history of settlement and migration, its many cultures, and its diverse geography (mountains, forests, plains, coasts, islands, and deserts).

Because of this, Tunisian leader Habib Bourguiba started a plan to make Tunisia more Arabic-speaking and "Tunisified." He spread free basic education to all Tunisians. This slowly reduced the mixing of European languages in Tunisian and increased the use of Standard Arabic. Also, the creation of the Établissement de la radiodiffusion-télévision tunisienne in 1966 and the spread of television helped dialects become more similar by the 1980s.

By then, Tunisian Arabic was used nationwide. It had six slightly different but fully understandable dialects: Tunis, Sahil, Sfax, southwestern, southeastern, and northwestern. Older dialects became less common and started to disappear. As a result, Tunisian became the main important language for communication in Tunisia. Tunisia became the most linguistically similar state in the Maghreb. However, some Berber dialects, Libyan and Algerian Arabic, and even some Tunisian dialects like the traditional urban women's dialect and Judeo-Tunisian Arabic almost disappeared from Tunisia.

After independence, Tunisian Arabic also began to be used more in literature and education. The Peace Corps taught Tunisian Arabic from 1966 to 1993. More studies were done, some using new methods like computers to create language collections (corpora). The publicly available Tunisian Arabic Corpus is one example. Other traditional studies looked at Tunisian sounds, word forms, and meanings. The language has been used to write novels since the 1990s and even a Swadesh list in 2012. Today, it is taught by many places, like the Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales in Paris (since 1916) and the Institut Bourguiba des Langues Vivantes in Tunis (since 1990). It is also an optional language in French high schools. In 1999, 1878 students took the Tunisian Arabic exam for the French Baccalauréat. Now, in France, there's a move to teach Maghrebi Arabic, mainly Tunisian Arabic, in basic education.

There were other attempts to use Tunisian Arabic in education. In 1977, Tunisian linguist Mohamed Maamouri suggested a project to teach basic education to older people using Tunisian Arabic. The goal was to make basic courses easier to understand for older people who did not learn Standard Arabic. However, this project was not put into action.

Today, how Tunisian Arabic is classified causes debates. This is because Arabic dialects form a continuum. Some linguists, like Michel Quitout and Keith Walters, see it as an independent language. Others, like Enam El-Wer, think it is a different dialect of Arabic that still depends on Arabic word forms and structures.

Also, its official recognition is still limited. France recognizes it as a minority language, part of Maghrebi Arabic, under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages of May 1999. However, the Constitutional Council of France did not agree to this charter because it conflicted with Article 2 of the French Constitution of 1958. In Tunisia, Tunisian Arabic had no official recognition or standardization until 2011. This was despite efforts by Tunisian professors Salah Guermadi and Hedi Balegh to prove that Tunisian is a language.

After the Tunisian revolution of 2011, where Tunisian Arabic was the main language used, efforts to get the language recognized grew stronger.

In 2011, the Tunisian Ministry of Youth and Sports launched a version of its official website in Tunisian Arabic. But this version was closed after a week. An online poll showed that 53% of the website's users were against using Tunisian Arabic on the site.

In 2013, the Kélemti initiative was started by Hager Ben Ammar, Scolibris, Arabesques Publishing House, and Valérie Vacchiani. Their goal was to encourage the creation and publishing of written materials about and in Tunisian Arabic.

In 2014, the Tunisian Association of Constitutional Law published a version of the Tunisian Constitution of 2014 in Tunisian Arabic.

In 2016, after two years of work, the Derja Association was launched by Ramzi Cherif and Mourad Ghachem. Their aims are to standardize Tunisian, create official spelling rules and word lists, promote its use in daily life, literature, and science, and get it officially recognized as a language in Tunisia and other countries. The Derja Association also gives an annual award, the Abdelaziz Aroui Prize, for the best work written in Tunisian Arabic.

Since the 2011 revolution, many novels have been published in Tunisian Arabic. The first was Taoufik Ben Brik's Kelb ben Kelb (2013). Other important novels have been written by Anis Ezzine and Faten Fazaâ (the first woman to publish a novel in Tunisian Arabic). Even though literary critics often criticize them, Tunisian Arabic novels have sold well. The first printing of Faten Fazaâ's third novel sold out in less than a month.

Special Features of Tunisian Arabic

Tunisian Arabic is a type of Arabic. It shares many features with other modern Arabic varieties, especially those from the Maghreb. Here are some of its special features compared to other Arabic dialects:

- It has a traditional consonant sound system. This is partly due to Berber influences. Sounds like /q/ and interdental fricatives (like 'th' in 'think') are generally kept. However, /q/ is often pronounced /ɡ/ in Bedouin dialects. The interdental fricatives are lost in the Mahdia dialect, the Jewish dialect of Tunis, and the Jewish dialect of Soussa.

- In city dialects, إنتِي [ˈʔɪnti] means "you" for both men and women. This means there is no difference in how verbs are formed for male and female "you." In rural areas, this difference is still kept. They use إنتَا /ʔinta/ for males and إنتِي /ʔinti/ for females, with different verb forms.

- It does not use a special prefix for verbs to show the indicative mood. This means there is no difference between indicative and subjunctive moods.

- It has a way to show ongoing actions (a progressive aspect). It uses the word قاعد [ˈqɑːʕɪd], which originally means "sitting." For actions that involve an object, it also uses the word في ['fi] "in."

- The future tense is shown by using the prefixes ماش [ˈmɛːʃ] or باش [ˈbɛːʃ] or ْبِش [ˈbəʃ] before the verb. This is similar to saying "will" + verb in English.

- It has unique words like فيسع [ˈfiːsɑʕ] "fast," باهي [ˈbɛːhi] "good," and برشة [ˈbærʃæ] "very much." For example, [ˈbɛːhi ˈbærʃæ] means "very good."

- Unlike most other Muslim countries, the greeting as-salamu alaykum is not the common greeting in Tunisia. Tunisians use عالسلامة [ʕɑsːˈlɛːmæ] (formal) or أهلا [æhlæ] (informal) to say hello. For goodbye, they use بالسلامة [bɪsːˈlɛːmæ] (formal) or the Italian ciao (informal). Less often, they use the Italian arrivederci. يعيشك [jʕɑjːʃɪk] means "thank you," instead of شكرا [ˈʃʊkræn]. However, Tunisians do use some phrases from Standard Arabic like بارك الله فيك [ˈbɑːræk ɑlˤˈlˤɑːhu ˈfiːk] and أحسنت [ʔɑħˈsænt] for thanks. But these are used as borrowed phrases, not in the same way as in Standard Arabic.

- The way verbs are made passive is influenced by Berber and is different from Classical Arabic. It is done by adding /t-/, /tt-/, /tn-/ or /n-/ to the beginning of the verb. The choice of prefix depends on the verb.

- Almost all educated Tunisians can speak French. French is widely used in business and for talking with foreigners. Mixing French words into Tunisian is common.

- Tunisian Arabic is an SVO language, meaning sentences usually go Subject-Verb-Object. It is also often a Null-subject language, where the subject is only said if it helps avoid confusion.

- Tunisian has more agglutinative structures (where words are formed by adding many parts) than Standard Arabic or other Arabic varieties. This was made even stronger by Turkish influence in the 17th century.

Tunisian Arabic Dialects

The Arabic dialects in Tunisia belong to either pre-Hilalian or Hilalian groups.

Before 1980, the pre-Hilalian group included old city dialects from Tunis, Kairouan, Sfax, Sousse, Nabeul and its Cap Bon region, Bizerte, old village dialects (Sahel dialects), and Judeo-Tunisian. The Hilalian group included the Sulaym dialects in the south and the Eastern Hilal dialects in central Tunisia. The latter were also spoken in eastern Algeria.

Today, due to dialects becoming more similar, the main Tunisian Arabic varieties are Northwestern Tunisian (also spoken in Northeastern Algeria), Southwestern Tunisian, Tunis dialect, Sahel dialect, Sfax dialect, and Southeastern Tunisian. All of these are Hilalian except for the Sfax dialect.

The Tunis, Sahel, and Sfax dialects (considered city dialects) use the sound [q] in words like قال /qaːl/ "he said." However, the southeastern, northwestern, and southwestern varieties (considered nomadic dialects) replace it with the sound [ɡ], as in /ɡaːl/. Also, only the Tunis, Sfax, and Sahel dialects use Tunisian sounds.

Northwestern and southwestern Tunisians speak Tunisian with Algerian Arabic sounds. This tends to simplify short vowels. Southeastern Tunisians speak Tunisian with Libyan Arabic sounds.

Additionally, the Tunis, Sfax, and urban Sahel dialects do not mark gender for the second person. So, the word إنتِي /ʔinti/, which is usually feminine, is used for both men and women. No feminine marking is used in verbs (inti mšīt). Northwestern, southeastern, and southwestern varieties keep the gender difference found in Classical Arabic (إنتَا مشيت inta mšīt for male, إنتِي مشيتي inti mšītī for female).

Furthermore, Tunis, Sfax, and Sahel dialects conjugate verbs like mšā and klā in the feminine third person past tense as CCāt. For example, هية مشات hiya mšāt. However, Northwestern, southeastern, and southwestern varieties conjugate them as CCat. For example, هية مشت hiya mšat.

Finally, each of the six dialects has its own specific words and patterns.

Tunis Dialect

The Tunis dialect is seen as the standard form of Tunisian Arabic. This is because it is used in media and teaching materials. It is spoken in the Northern East of Tunisia, around Tunis, Cap Bon, and Bizerte. It has a special feature not found in some other Tunisian Arabic dialects: it clearly distinguishes between three short vowels. It also tends to pronounce [æ] as [ɛ]. The āš suffix, used at the end of question words, is pronounced as an [ɛ:h].

Sahel Dialect

The Sahel dialect is known for using ānī instead of ānā for "I." It also pronounces wā as [wɑː]. The sounds ū and ī are pronounced as [oː] and [eː] when they replace the common Classical Arabic diphthongs /aw/ and /aj/. For example, زيت zīt is pronounced as [ze:t], and لون lūn is pronounced as [lɔːn]. Also, if ā is at the end of a word that is not specific (indefinite) or has "il-" (definite), this final ā is pronounced as [iː]. For example, سماء smā is pronounced as [smiː]. If a word starts with two consonants, and the first is /θ/ or /ð/, these sounds are pronounced as [t] and [d] respectively. For example, ثلاثة /θlaːθa/ is pronounced as [tlɛːθæ]. The Sahel dialect also uses مش miš instead of موش mūš to say "not" for a future action.

Sfax Dialect

The Sfax dialect is known for keeping the Arabic diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/. It also keeps the short /a/ between two consonants. It uses وحيد wḥīd instead of وحود wḥūd for the plural of "someone."

Other dialects have changed these diphthongs to /iː/ and /uː/. They also drop the short /a/ between the first and second consonant of a word. The Sfax dialect also changes short /u/ to short /i/ when it is at the beginning of a word or right after the first consonant. For example, خبز /χubz/ is pronounced as [χibz].

It is also known for using specific words, like baṛmaqnī for "window." Furthermore, it changes [ʒ] to [z] when it is at the beginning of a word and that word has [s] or [z] in the middle or end. For example, جزّار /ʒazzaːrˤ/ is pronounced as [zæzzɑːrˤ], and جرجيس /ʒarʒiːs/ is pronounced as [zærzi:s].

Unlike other Tunisian dialects, the Sfax dialect does not shorten the last long vowel at the end of a word. It is also known for some specific verbs like أرى aṛā (to see). It uses the words هاكومة hākūma for "those" and هاكة hāka (male) and هٰاكي hākī (female) for "that." Other dialects use هاذوكم hāðūkum and هاذاكة hāðāka (male) and هاذيكة hāðākī (female). Finally, when conjugating mūš as a modal verb, it uses ماهواش māhūwāš instead of ماهوش māhūš, ماهياش māhīyāš instead of ماهيش māhīš, ماحناش māḥnāš instead of ماناش mānāš, and ماهوماش māhūmāš instead of ماهمش māhumš.

The Sfax dialect is also known for having many diminutives (words that mean a smaller or cuter version of something). For example:

- قطيطس qṭayṭas (little or friendly cat) for قطّوس qaṭṭūs (cat).

- كليب klayib (little or friendly dog) for كلب kalb (dog).

Northwestern Dialect

The northwestern dialect pronounces 'r' as [rˤ] when it comes before an 'ā' or 'ū'. Also, it changes [ʒ] to [z] when it is at the beginning of a word and that word has [s] or [z] in the middle or end. It also pronounces 'ū' and 'ī' as [o:] and [e:] respectively, when they are in a strong or uvular sound environment. The northwestern dialect uses مش miš, pronounced as [məʃ], instead of مانيش mānīš to say "not" for a future action. Similarly, when conjugating مش miš as a modal verb, it uses مشني mišnī instead of مانيش mānīš, مشك mišk instead of ماكش mākš, مشّو miššū instead of موش mūš and ماهوش māhūš, مشها mišhā instead of ماهيش māhīš, مشنا mišnā instead of ماناش mānāš, مشكم miškum instead of ماكمش mākumš, and مشهم mišhum instead of ماهمش māhumš. Furthermore, the northwestern dialect uses نحنا naḥnā instead of أحنا aḥnā for the plural "we." In the southern part of this dialect, like El Kef, people use ناي nāy or ناية nāya instead of آنا ānā (meaning "I"), except in Kairouan, where they use يانة yāna.

Southeastern Dialect

The southeastern dialect has a different way of conjugating verbs that end with ā in the third person plural. Instead of adding the usual ū suffix after the vowel ā, they drop the ā and then add the ū. For example, مشى mšā is conjugated as مشوا mšū instead of مشاوا mšāw for the third person plural. Also, it changes [ʒ] to [z] at the beginning of a word when that word has [s] or [z] in the middle or end. Like the Sahel dialect, it pronounces /uː/ and /iː/ as [oː] and [eː] respectively, when they replace the common Classical Arabic diphthongs /aw/ and /aj/. This dialect also uses أنا anā instead of آنا ānā (meaning "I"), حنا ḥnā instead of أحنا aḥnā (meaning "we"), إنتم intumm (male) and إنتن intinn (female) instead of انتوما intūma (meaning "you" in plural), and هم humm (male) and هن hinn (female) instead of هوما hūma (meaning "they").

Southwestern Dialect

The southwestern dialect has a different way of conjugating verbs that end with ā in the third person plural. Speakers of this dialect drop the ā and then add the ū. For example, مشى mšā is conjugated as مشوا mšū for the third person plural. This dialect also uses ناي nāy instead of آنا ānā (meaning "I"), حني ḥnī instead of أحنا aḥnā (meaning "we"), إنتم intumm (male) and إنتن intinn (female) instead of انتوما intūma (meaning "you" in plural), and هم humm (male) and هن hinn (female) instead of هوما hūma (meaning "they"). Additionally, it pronounces 'ū' and 'ī' as [o:] and [e:] respectively, in strong or uvular sound environments.

Where is Tunisian Arabic Used?

Tunisian Arabic is the main language for Arabic speakers in Tunisia. It is also the second language for the Berber minority in the country, especially in some villages in Djerba and Tatawin.

However, Tunisian Arabic is usually the "low" language in a situation called diglossia, where Standard Arabic is the "high" language. This means Tunisian Arabic is mostly used for speaking. Its written and cultural use only started in the 17th century and grew steadily from the 20th century. Now, it is used for many things, including talking, politics, literature, theater, and music.

Tunisian Arabic in Society

From the 1990s, Tunisians started writing in Tunisian Arabic when using the Internet, especially on social networking sites and in text messages. This became even more common during the 2011 street protests that ended the rule of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Text messaging and social networking played a big part in these events.

In religion, Tunisian Arabic is not widely used to promote Islam, though some efforts are being made. In Christianity, Tunisian Arabic is used more, starting with a New Testament translation in 1903. Since 2013, Tunisian author and linguist Mohamed Bacha has published popular books to learn Tunisian Arabic and explore Tunisian culture for English speakers. These include Tunisian Arabic in 24 lessons, Tunisian Arabic in 30 lessons, Tunisian Arabic - English dictionary, and Tunisian folklore: folktales, songs, proverbs. The folklore book shares Tunisia's oral stories, songs, and proverbs, adapted into written form and translated into English. He also created multilingual versions of folktales like Jabra and the lion (in Tunisian Arabic, English, French) and Eternal Classic Songs of Tunisia (Tunisian, English, French).

Tunisian Arabic in Literature

Before Tunisia became independent, there were many folk tales and poems in Tunisian Arabic. These were mostly passed down by word of mouth, told by traveling storytellers and poets at markets and festivals. The most important of these tales are il-Jāzya il-hlālīya (الجازية الهلالية) and ḥkāyat ummī sīsī w il-ðīb (حكاية أمّي سيسي والذيب). A few years after independence, the popular ones were recorded for ERTT broadcasts in Tunisian Arabic by Abdelaziz El Aroui. Others were translated, mainly into French and Standard Arabic. The recorded Tunisian folktales were written down in Tunisian Arabic using Arabic script only in the 2010s, thanks to the Kelemti Association and Karen McNeil.

For novels and short stories, most authors who know Tunisian Arabic well prefer to write in Standard Arabic or French. But since Taht Essour, especially Ali Douagi, started using Tunisian Arabic for dialogues in novels and some newspapers, dialogues in Tunisian novels written in Standard Arabic began to be written in Tunisian Arabic using the Arabic script.

However, since the early 1990s, Hedi Balegh started a new trend in Tunisian literature. He was the first to translate a novel into Tunisian Arabic in 1997. He also collected Tunisian sayings and proverbs in 1994, using Arabic script. Some authors, like Tahar Fazaa (in Tšanšīnāt Tūnsīya) and Taoufik Ben Brik (in Kalb Bin Kalb and Kawāzākī), followed him. They used Tunisian Arabic to write novels, plays, and books.

The first plays in Tunisian Arabic were made by the Tunisian-Egyptian Company right after World War I. They faced some challenges but became widely accepted in Tunisia by the end of World War II. After Tunisia gained independence, the government supported the development of theater in Tunisian Arabic. This led to many important plays being created between 1965 and 2005, following world literature trends. Key authors included Jalila Baccar, Fadhel Jaïbi, and members of the National Theatre Troups in the Medina of Tunis, El Kef, and Gafsa.

Now, plays are almost always written in Tunisian Arabic, unless they are set in a historical period. Plays written in Tunisian Arabic are seen as important and valuable.

Since the 2011 Tunisian Revolution, there has been a trend of novels written in Tunisian Arabic. After Taoufik Ben Brik's Kalb Bin Kalb in 2013, novels have been written by Faten Fazaâ, Anis Ezzine, Amira Charfeddine, and Youssef Chahed. Translations of Tunisian and world literature into Tunisian Arabic have been done by Dhia Bousselmi and Majd Mastoura.

Tunisian Arabic in Music

The oldest known lyrics written in Tunisian date back to the 17th century. Abu el-Hassan el-Karray, who died in 1693 in Sfax, wrote a poem in Tunisian Arabic when he was young.

Tunisian Arabic songs really started to be written in the early 19th century. Tunisian Jews in the Beylik of Tunis began writing songs about love, betrayal, and other topics. This trend grew in the early 20th century and influenced Tunisian ma'luf and folk music. Judeo-Tunisian songs became very popular in the 1930s, with artists like Cheikh El Afrit and Habiba Msika.

This trend was helped by the creation of Radio Tunis in 1938 and the Établissement de la radiodiffusion-télévision tunisienne in 1966. These allowed musicians to share their work more widely and helped spread Tunisian Arabic in songs.

At the same time, popular music developed in the early 19th century. It used Tunisian Arabic poems with Tunisian instruments like the mizwad. The National Troupe of the Popular Arts, created in 1962, promoted this music. Later, Ahmed Hamza and Kacem Kefi further developed Tunisian music by adapting and promoting popular songs. Both were from Sfax and were influenced by Mohamed Ennouri and Mohamed Boudaya, leading popular music masters in that city. Today, this type of music is very popular.

Tunisian Arabic became the main language for writing song lyrics in Tunisia. Even many technical words in music have Tunisian Arabic equivalents.

In the early 1990s, underground music in Tunisian Arabic appeared. This was mainly rap and was not successful at first due to lack of media attention. Tunisian underground music, mostly in Tunisian Arabic, became popular in the 2000s. This was thanks to its spread on the Internet. It grew to include other styles like reggae and rock.

In 2014, the first opera songs in Tunisian Arabic appeared. These were by Yosra Zekri, with lyrics by Emna Rmilli and music by Jalloul Ayed. In 2018, the Tunisian linguist Mohamed Bacha published Eternal Classic Songs of Tunisia. This book features famous classic Tunisian songs performed by popular artists from the 1950s to the 1980s. The lyrics are in natural Tunisian Arabic. The music was composed by great musicians like Boubaker El Mouldi and Mohamed Triki. Poets like Omar Ben Salem wrote the lyrics. Some of the best classic Tunisian songs were chosen from traditional folk music.

Tunisian Arabic in Cinema and Mass Media

Many of the few local movies made since 1966 tried to show new social changes, development, identity search, and the impact of modern life. These movies were made in Tunisian Arabic. Some of them became somewhat successful outside Tunisia, such as La Goulette (ḥalq il-wād, 1996), Halfaouine: Child of the Terraces (ʿaṣfūr il-sṭaḥ, 1990), and The Ambassadors (il-sufaṛā, 1975).

Television and radio programs in Tunisian Arabic officially began in 1966 with the creation of the Établissement de la Radiodiffusion-Télévision Tunisienne. Tunisian Arabic is now widely used for almost all television and radio programs. Exceptions include news, religious programs, and historical dramas. There are even several cartoon series translated into Tunisian Arabic, like Qrīnaṭ il-šalwāš and Mufattiš kaʿbūṛa in the 1980s. Also, foreign Television series began to be translated into Tunisian Arabic in 2016. The first foreign TV series translated was Qlūb il-rummān, adapted by Nessma TV from the Turkish series Kaderimin Yazıldığı Gün.

Some Tunisian Arabic works have won awards in the wider Arab world, such as the ASBU Festival First Prize in 2015 and the Festival of Arab Media Creation Prize in 2008.

Since the 1990s, mass media advertisements increasingly use Tunisian Arabic. Many advertising signs have their slogans and company names written in Tunisian.

However, the main newspapers in Tunisia are not written in Tunisian Arabic. Although there were attempts to create humorous newspapers in Tunisian Arabic, like kull šay b- il-makšūf, which was published from 1937 to 1959. The leading newspapers are still written in Modern Standard Arabic or Standard French. However, cartoons in most of them can be written in Tunisian.

How Tunisian Arabic is Written

Arabic Script

The Arabic script used for Tunisian Arabic is mostly the same as for Standard Arabic. However, it includes extra letters for sounds like /g/ (ڨ), /v/ (ڥ), and /p/ (پ).

The first known use of Arabic script for Tunisian was in the 17th century, when Sheykh Karray wrote poems in Tunisian Arabic for religious purposes. But writing Tunisian Arabic was not common until 1903, when the Gospel of John was written down in Tunisian Arabic using Arabic script. After World War I, using Arabic script for Tunisian Arabic became very common with the works of Taht Essour. Today, it is the main way Tunisian Arabic is written, even in published books. However, the rules for writing Tunisian Arabic are not fully set and can change from one book to another.

In 2014, Ines Zribi and her team suggested a standard way to write Tunisian Arabic. This method tries to remove simplified sounds by comparing Tunisian Arabic words to their original forms in Modern Standard Arabic. While this method is important, it does not show the difference between [q] and [g]. It also does not include some important sounds mainly found in borrowed words.

Latin Script

Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft Umschrift

In 1845, the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (DMG), a German scientific group for studying Eastern languages, was formed in Leipzig. They soon created a system for writing Arabic in Latin script. This system used an extended Latin alphabet and macrons for long vowels to show Arabic sounds. However, this DMG system was first used for Tunisian only after the French Protectorate of Tunisia began in 1881.

The first language study on Tunisian was done by German linguist Hans Stumme from 1893 to 1896. He wrote Tunisian Arabic using the DMG system. Also, from 1897 to 1935, French members of the DMG, like William Marçais, did many language studies. These included collections of words, grammar books, dictionaries, and other studies. By 1935, the DMG system had many unique letters and marks for Tunisian that were not used for Arabic, such as à, è, ù, and ì for short and stressed vowels. Because of this, the 19th international congress of orientalists in Rome, from September 23 to 29, 1935, adopted a simpler version of the DMG system specifically for Arabic dialects. From 1935 to 1985, most linguists working on Tunisian Arabic, such as Gilbert Boris and Hans Rudolf Singer, used the modified DMG.

As of 2016, the modified DMG is still used by groups like SIL International and the University of Vienna for Tunisian Arabic written collections and language books.

Other Ways of Writing

Even though the DMG system was widely used in early studies of Tunisian, some attempts were made to create other Latin scripts. The goal was to have a simpler and easier-to-use Latin writing system than DMG. Another goal was to solve the problem of converting between scripts, as the DMG method for Tunisian was based on sounds, not grammar.

The first successful attempt to create a specific Latin script for Tunisian was the Practical Orthography of Tunisian Arabic, made by Joseph Jourdan in 1913. It used French consonant and vowel combinations and sounds to write non-Latin sounds. For example, kh was used for /χ/, ch for /ʃ/, th for /θ/, gh for /ʁ/, dh for /ð/ or /ðˤ/, and ou for /u:/. The letter a was for /a:/ and /ɛː/, i for /i:/, and e for short vowels. This method worked well because it did not need extra Latin letters and could be written efficiently. Joseph Jourdan used it in his later language works on Tunisian Arabic until 1956. It is still used today in French books to write Tunisian Arabic. This method was used in 1995 by Tunisian Arabizi, a way of writing Arabic for chat, which changed consonant combinations into numbers. It uses 2 for a glottal stop, 3 for /ʕ/, 5 for /χ/, 6 for /tˤ/, 7 for /ħ/, 8 for /ʁ/, and 9 for /q/. The ch, dh, and th combinations were kept in Tunisian Arabizi. Vowels are written based on their sound, not their length. For example, 'a' is used for short and long [ɐ] and [æ], 'e' for short and long [ɛ] and [e], 'u' for short and long [y], 'eu' for short and long [œ], 'o' for short and long [o], 'ou' for short and long [u], and 'i' for short and long [i] and [ɪ]. Sometimes, users drop short vowels to show the difference. Like other Arabic chat alphabets, its use spread a lot in the 1990s, mainly among young Tunisians. Today, it is mostly used on social networks and mobile phones. During the Tunisian Revolution of 2011, Tunisian Arabizi was the main way messages were sent online. After 2011, more interest was given to Tunisian Arabizi. In 2013, a short grammar book about Tunisian, written with Tunisian Arabizi, was published. In 2016, Ethnologue recognized Tunisian Arabizi as an official informal way to write Tunisian. However, this chat alphabet is not standardized and is seen as informal because Arabic sounds are written with both numbers and letters. Using numbers and letters at the same time made writing Tunisian difficult for users and did not solve the language problems faced by the Practical Transcription.

Even though they are popular, both methods have problems. For example, there can be confusion between letter combinations. Also, the number of letters per sound is always more than one. And single consonants can be written the same way as letter combinations. Plus, there is no clear way to tell the difference between /ð/ and /ðˤ/.

A translation of Le Petit Nicolas by Dominique Caubet uses a phonetic way of writing.

Separately, another Latin script writing method was created by Patrick L. Inglefield and his team from Peace Corps Tunisia and Indiana University in 1970. Letters in this method can only be written in lowercase. Even 'T' and 'S' are not the same as 't' and 's', as 'T' is used for /tˤ/ and 'S' for /sˤ/. Also, three extra Latin letters are used: 3 (/ʕ/), ø (/ð/), and ħ (/ħ/). Four common English letter combinations are used: dh (/ðˤ/), gh (/ʁ/), th (/tˤ/), and sh (/ʃ/). To tell these combinations apart from single letters that look similar, the combinations are underlined. For vowels, they are written as å (glottal stop or /ʔ/), ā (/æ/), ā: (/ɛ:/), a (Short an or /a/), a: (long an or /a:/), i (short i or /i/), i: (long i or /i:/), u (short u or /u/), u: (Long u or /u:/). This method was used in Peace Corps books about Tunisian Arabic until 1993, when Peace Corps Tunisia stopped its activities.

After years of working on writing Tunisian based on sounds, linguists decided that writing should mainly be based on grammar. Timothy Buckwalter created a way to write Arabic texts based on spelling for his work at Xerox. Buckwalter transcription was made to avoid the problem of simplified sounds in spoken Modern Standard Arabic affecting how the language's word forms were analyzed. In 2004, Tunisian linguist Mohamed Maamouri suggested using the same writing system for Arabic dialects, especially Tunisian. This idea was later developed by Nizar Habash and Mona Diab in 2012 into a CODA-based Buckwalter transliteration. This system removes sound simplifications in Arabic dialects by comparing dialect structures to their Modern Standard Arabic equivalents. In 2013, a full guide on how to use the Buckwalter transliteration for Tunisian was published by Ines Zribi and her team from the University of Sfax. A method for analyzing word forms and a standard spelling for Tunisian Arabic using this system were published by 2014. However, this method is currently only used for computers. People do not use it because it includes some non-letter symbols as letters. Also, S, D, and T do not match the same sounds as s, d, and t. Furthermore, 'p' does not stand for /p/ but for ﺓ. Even the changed version of Buckwalter transliteration, suggested by Nizar Habash and others in 2007, which replaced non-letter symbols with extra Latin letters, did not solve the other problems of the original Buckwalter transliteration. That is why neither version of Buckwalter transliteration was adopted for daily use in writing Tunisian Arabic. They are only used for computer language processing.

Tunisian Arabic Vocabulary

Words Not From Arabic

The most obvious difference between Tunisian and Standard Arabic is the many words from Latin and Berber origins, or borrowed from Italian, Spanish, French, and Turkish. For example, "electricity" is كهرباء /kahrabaːʔ/ in Standard Arabic. In Tunisian Arabic, it is تريسيتي trīsītī (mostly used by older people), which comes from the French word électricité. Other words borrowed from French include برتمان buṛtmān (flat) and بياسة byāsa (coin). Also, there are words and structures from Turkish, such as ڨاوري gāwrī (foreigner) (from Gavur). The suffix /-ʒi/ is also from Turkish and is added to words to mean professions, like بوصطاجي būṣṭājī (post officer) and كوّارجي kawwāṛjī (football player). Below are some examples of words from Latin, French, Italian, Turkish, Berber, Greek, or Spanish:

| Tunisian Arabic | Standard Arabic | English | Origin of Tunisian Arabic Word |

|---|---|---|---|

| بابور ḅaḅūr | سفينة /safiːna/ | ship | Turkish: vapur meaning "steamboat" |

| باكو bakū | صندوق /sˤundu:q/ | package | Italian: pacco |

| بانكة ḅanka | بنك /bank/ | bank | Italian: banca |

| بلاصة bḷaṣa | مكان /makaːn/ | place | Spanish:plaza |

| داكردو dakūrdū | حسنا /ħasanan/ | okay | Italian: d'accordo |

| فيشتة fišta | عيد /ʕiːd/ | holiday | Latin: festa |

| كرّوسة kaṛṛūsa | عربة /ʕaraba/ | carriage | Italian: carrozza |

| كيّاس kayyās | طريق معبد /tˤarīq maʕbad/ | roadway | Spanish: calles |

| كوجينة kūjīna | مطبخ /matˤbax/ | kitchen | Italian: cucina |

| كسكسي kusksī | كسكسي /kuskusi/ | couscous | Berber: seksu |

| كلسيطة kalsīta | جورب /jawrab/ | sock | Italian: calzetta |

| قطّوس qaṭṭūs | قط /qitˤː/ | cat | Latin: cattus |

| سبيطار sbīṭaṛ | مستشفىً /mustaʃfa:/ | hospital | Latin: hospitor |

| سفنارية sfinārya | جزر /jazar/ | carrot | Greek: σταφυλῖνος ἄγριος (stafylīnos ā́grios) |

These words are different from when Tunisians actually use French words or sentences in daily speech (called codeswitching). Codeswitching is common in everyday talk and business. However, many French words are used within Tunisian Arabic conversations without being changed to Tunisian sounds. The French 'r' [ʁ] is often replaced with [r], especially by men. For example, many Tunisians might ask "How are you?" using the French "ça va?" in addition to the Tunisian لاباس (lebes). It can be hard to tell if this is using French or borrowing a word.

Generally, borrowed words are adapted to Tunisian sounds over time until they are pronounced only with basic Tunisian Arabic sounds. For example, the French word apartement became برتمان buṛtmān, and the Italian word pacco became باكو bakū.

Changes in Word Meanings

The biggest differences between Tunisian and Standard Arabic are not from other languages. Instead, they come from a change in meaning of some Arabic word roots. For example, /x-d-m/ means "serve" in Standard Arabic but "work" in Tunisian Arabic. Meanwhile, /ʕ-m-l/ means "work" in Standard Arabic but has a broader meaning of "do" in Tunisian Arabic. And /m-ʃ-j/ in Tunisian Arabic means "go" rather than "walk" as in Standard Arabic.

Generally, meaning changes happen when the way a society lives affects its language. So, the social situation and thoughts of the speakers made them change the meaning of some words. This helped their language fit their situation, which is exactly what happened in Tunisia. The influence of French and other languages also helped these meaning changes in Tunisian.

New Words from Fusing Old Ones

In Tunisian, some new words and structures were created by combining two or more words. Almost all question words are formed this way. These question words often start or end with the sound š or āš. This should not be confused with the negation mark, š, which is added to verbs, as in mā mšītš ما مشيتش (I did not go).

The table below compares various question words in Tunisian, Standard Arabic, and English:

| Tunisian Arabic | Construction | Standard Arabic | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| škūn شكون | āš + kūn آش + كون | من /man/ | who |

| šnūwa شنو (masc.) šnīya (fem.) شني āš آش |

āš + n + (h)ūwa آش + هو āš + n + (h)īya آش + هي āš آش |

ماذا /maːða/ | what |

| waqtāš وقتاش | waqt + āš وقت + آش | متى /mata/ | when |

| lwāš لواش | l- + āš ل + آش | لماذا /limaːða/ | for what reason |

| ʿlāš علاش | ʿlā + āš على + آش | لماذا /limaːða/ | why |

| kīfāš كيفاش | kīf + āš كيف + آش | كيف /kajfa/ | how |

| qaddāš قدّاش | qadd + āš قدّ + آش | كم /kam/ | how much |

| mnāš مناش | min + āš من + آش | من أين /man ʔajna/ | from what |

| fāš فاش | fī + āš في + آش | في من /fi man/ | in what, what |

| wīn وين | w + ayn و + اين | أين /ʔajna/ | where |

Some question words can combine with other parts of speech, like prepositions and object pronouns. For example, "who are you" becomes شكونك إنت škūnik intī or simply شكونك škūnik. "How much is this" becomes بقدّاش b-qaddāš.

Another example of word fusion in Tunisian is how numbers from 11 to 19 are formed. They are said as one word. This word is made of the number minus 10, plus the suffix طاش ṭāš. This suffix comes from the Standard Arabic word عَشَرَ /ʕaʃara/. These numbers are: احداش aḥdāš (11), اثناش θṇāš (12), ثلطّاش θlaṭṭāš (13), أربعطاش aṛbaʿṭāš (14), خمسطاش xmasṭāš (15), سطّاش sitṭāš (16), سبعطاش sbaʿṭāš (17), ثمنطاش θmanṭāš (18), and تسعطاش tsaʿṭāš (19).

Creating New Words from Patterns

In Tunisian Arabic, like in other Semitic languages, new words are created using a root and pattern system. This is also known as the Semitic root. This means new words can be made by combining a root (usually three letters with a meaning) with a pattern (which shows the role of the object in the action). For example, K-T-B is a root meaning to write. The pattern مفعول maf‘ūl means that the object received the action. So, combining the root and pattern gives maKTūB, meaning "something that was written."

How Tunisian Arabic Sounds

There are several differences in pronunciation between Standard and Tunisian Arabic. Nunation (adding 'n' sounds to the end of words) does not exist in Tunisian Arabic. Short vowels are often left out, especially if they are at the end of an open syllable. This was probably encouraged by the Berber language influence.

However, Tunisian Arabic has some unique features, like metathesis.

Metathesis

Metathesis is when the first vowel of a word changes its position. This happens when a verb (not yet conjugated) or a noun (without a suffix) starts with CCVC (two consonants, a short vowel, then a consonant). When a suffix is added to the noun or the verb is conjugated, the first vowel moves. The word then starts with CVCC.

For example:

- (he) wrote in Tunisian Arabic is كتب ktib. (she) wrote becomes كتبت kitbit.

- some stuff in Tunisian Arabic is دبش dbaš. my stuff becomes دبشي dabšī.

| The English pronoun | Pronoun | Dbaš (stuff) | Wdhin (ear) | 3mor (age) |

| I | Ena | Dabši | Widhni | 3omri |

| You (singular) | Enty | Dabšk | Widhnk | 3omrk |

| He | Houa | Dabšu | Withnu | 3omru |

| She | Hia | Dbašha | Wthinha | 3morha |

| We | Aħna | Dbašna | Wthinna | 3morna |

| You (plural) | Entuma | Dbaškom | Wthinkom | 3morkom |

| They | Huma | Dbaš'hom' | Wthinhom | 3morhom |

Word Stress

Word stress in Tunisian Arabic is not used to tell words apart. It is decided by how the word's syllables are built.

- Stress falls on the last syllable if it has two consonants at the end: سروال sirwāl (trousers).

- Otherwise, it falls on the second-to-last syllable, if there is one: جريدة jarīda (newspaper).

- If a word has only one syllable, the stress is on that syllable: مرا mṛa (woman).

- Added parts (affixes) are treated as part of the word: نكتبولكم niktbūlkum (we write to you).

For example:

- جابت jābit (She brought).

- ما جابتش mā jābitš (She did not bring).

Sound Changes (Assimilation)

Assimilation is a process where sounds change to become more like nearby sounds in Tunisian Arabic. Here are some possible assimilations:

| /ttˤ/ > /tˤː/ | /tˤt/ > /tˤː/ | /χh/ > /χː/ | /χʁ/ > /χː/ |

| /tɡ/ > /dɡ/ | /fd/ > /vd/ | /ħh/ > /ħː/ | /nl/ > /lː/ |

| /sd/ > /zd/ | /td/ > /dː/ | /dt/ > /tː/ | /ln/ > /nː/ |

| /hʕ/ > /ħː/ | /tð/ > /dð/ | /hħ/ > /ħː/ | /nr/ > /rː/ |

| /nf/ > /mf/ | /qk/ > /qː/ | /kq/ > /qː/ | /lr/ > /rː/ |

| /ndn/ > /nː/ | /ħʕ/ > /ħː/ | /ʁh/ > /χː/ | /ʕh/ > /ħː/ |

| /ʃd/ > /ʒd/ | /fC/ > /vC/ | /bC/ > /pC/ | /nb/ > /mb/ |

| /ʕħ/ > /ħː/ | /tz/ > /d͡z/ | /tʒ/ > /d͡ʒ/ |

- Only if C is a voiced consonant.

- Only if C is a voiceless consonant.

Consonant Sounds

The Tunisian Arabic qāf can be pronounced as [q] in city dialects and [ɡ] in nomadic dialects. For example, he said is [qɑːl] or [ɡɑːl]). However, some words always have the [ɡ] sound, no matter the dialect. For example, cow is always [baɡra], and a type of date is always [digla]. Sometimes, changing [g] to [q] can change a word's meaning. For example, garn means "horn," and qarn means "century."

Interdental fricatives (like 'th' in 'think') are also kept in many situations, except in the Sahil dialect.

Furthermore, Tunisian Arabic combined the sounds /dˤ/ ⟨ض⟩ and /ðˤ/ ⟨ظ⟩.

| Lip Sounds | Between Teeth | Tooth/Ridge | Palate | Back Palate | Uvula | Throat | Voice Box | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | |||||||

| Nasal | m m | (mˤ) ṃ | n n | (nˤ) ṇ | ||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | (p) p | t t | tˤ ṭ | k k | q q | (ʔ) | |||||

| voiced | b b | (bˤ) ḅ | d d | ɡ g | ||||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | (t͡s) ts | (t͡ʃ) tš | |||||||||

| voiced | (d͡z) dz | |||||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f f | θ þ | s s | sˤ ṣ | ʃ š | χ x | ħ ḥ | h h | |||

| voiced | (v) v | ð ð | ðˤ ḍ | z z | (zˤ) ẓ | ʒ j | ʁ ġ | ʕ ʿ | ||||

| Trill | r r | rˤ ṛ | ||||||||||

| Approximant | l l | ɫ ḷ | j y | w w | ||||||||

Notes on Sounds:

- The strong consonants /mˤ, nˤ, bˤ, zˤ/ are rare. Most are found in words not from Arabic. It is not always easy to find word pairs that show the difference for these sounds. However, examples show that these rare forms are not just different ways of saying other sounds. For example:

* /baːb/ [bɛːb] "door" and /bˤaːbˤa/ [ˈbˤɑːbˤɑ] "Father" * /ɡaːz/ [ɡɛːz] "petrol" and /ɡaːzˤ/ [ɡɑːzˤ] "gas" These strong consonants appear before or after the vowels /a/ and /aː/. Another idea is that the suggested different ways of saying /a/ and /aː/ are actually different sounds. In this case, the rare strong consonants would be the different ways of saying other sounds.

- /p/ and /v/ are found in words not from Arabic. They are usually replaced by /b/, as in ḅāḅūr and ḅāla. However, they are kept in some words, like pīsīn and talvza.

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡z/ are rarely used. Examples include tšīša, dzīṛa, and dzāyir.

- The glottal stop /ʔ/ (a sound like the break in "uh-oh") is usually dropped. But it tends to appear in formal speech and in words borrowed from Standard Arabic. This often happens at the beginning of verbal nouns, but also in other words like /biːʔa/ "environment" and /jisʔal/ "he asks." However, many speakers (especially less educated ones) replace /ʔ/ with /h/ in the latter word.

- Like in Standard Arabic, shadda (doubling a consonant sound) is very likely to happen in Tunisian. For example, haddad هدد means "to threaten."

Vowel Sounds

There are two main ways to understand Tunisian vowels:

- Three vowel qualities: /a, i, u/. And many strong consonants: /tˤ, sˤ, ðˤ, rˤ, lˤ, zˤ, nˤ, mˤ, bˤ/. The vowel /a/ has different sounds near throat sounds (strong, uvular, and pharyngeal consonants) ([ɐ], [ä]). It has other sounds near non-throat consonants ([æ]).

- Four vowel qualities: /æ, ɐ, i, u/. And only three main strong consonants: /tˤ, sˤ, ðˤ/. The other strong consonants are just different ways of saying sounds found near /ɐ/.

The first way of understanding is suggested by comparing other Maghrebi Arabic dialects, like Algerian and Moroccan Arabic. In these dialects, the same thing happens with vowels /u/ and /i/.

No matter how they are analyzed, the Hilalian influence added the vowels /eː/ and /oː/ to the Sahil and southeastern dialects. These two long vowels come from the diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/.

| Front | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||

| short | long | long | short | long | ||

| Close | ɪ i | iː ī | (yː) ü | u u | uː ū | |

| Open-mid | oral | eː ā | (œː) ë | (ʊː) ʊ | (oː) o | |

| nasal | (ɛ̃) iñ | (ɔ̃) uñ | ||||

| Open | (ɑ̃) añ | |||||

| oral | æ a | ɐ a | ɐː ā | |||

- If we assume that throat sounds are a feature of consonants, most dialects have three vowel qualities: /a, i, u/. These are also distinguished by length, like in Standard Arabic.

- The length difference is not present at the end of a word. A final vowel is pronounced long in stressed one-syllable words (for example, جاء jā [ʒeː] he came). Otherwise, it is short.

- In places where there are no throat sounds, the open vowel /a/ is [e] in stressed syllables. It is [æ] or [ɛ] in unstressed syllables. In places with throat sounds, the open vowel is [ɑ].

- /ɔː/ and nasal vowels are rare in native words, especially in most Tunisian varieties and the Tunis dialect. Examples include منقوبة mañqūba and لنڨار lañgār. They mainly appear in words borrowed from French. /yː/ and /œː/ only exist in French loanwords.

- Unlike other Maghrebi dialects, short u and i are shortened to [o] and [e] when they are between two consonants, unless they are in stressed syllables.

Syllables and Pronunciation Simplification

Tunisian Arabic has a very different syllable structure from Standard Arabic, like all other Northwest African varieties. Standard Arabic can only have one consonant at the beginning of a syllable, followed by a vowel. But Tunisian Arabic often has two consonants at the start of a syllable. For example, Standard Arabic for book is كتاب /kitaːb/, while in Tunisian Arabic it is ktāb.

The main part of a syllable (the vowel sound) can have a short or long vowel. At the end of the syllable, it can have up to three consonants, like in ما دخلتش (/ma dχaltʃ/ I did not enter). Standard Arabic can have no more than two consonants in this position.

Syllables that are not at the end of a word and only have a consonant and a short vowel (light syllables) are very rare. They usually appear in words borrowed from Standard Arabic. Short vowels in this position have generally been lost, leading to many words starting with two consonants. For example, جواب /ʒawaːb/ reply is borrowed from Standard Arabic. But the same word naturally developed into /ʒwaːb/, which is the usual word for letter.

Besides these features, Tunisian Arabic is also known for pronouncing words differently based on their spelling and position in a text. This is called pronunciation simplification and has four rules:

- [iː] and [ɪ], at the end of a word, are pronounced [i] and [uː]. Also, [u] is pronounced [u], and [aː], [ɛː], [a], and [æ] are pronounced [æ]. For example, yībdā is practically pronounced as [jiːbdæ].

- If a word ends with a vowel and the next word starts with a short vowel, the short vowel and the space between the two words are not pronounced (this is called Elision). This can be clearly seen when Arabic texts are compared to their Latin sound-based writings in some works.

- If a word starts with two consonants in a row, an extra [ɪ] sound is added at the beginning.

- A sequence of three consonants, not followed by a vowel, is broken up by adding an extra [ɪ] before the third consonant. For example: يكتب yiktib, يكتبوا yiktbū.

How Words are Formed (Morphology)

Nouns and adjectives in Tunisian Arabic are divided into those that form a regular plural and those that form an irregular plural. Some nouns in Tunisian Arabic even have dual forms (for two of something). Irregular or broken plurals are generally similar to those in Standard Arabic. Gender change for singular nouns and adjectives is done by adding an -a suffix. However, this usually cannot happen for most plural nouns.

Tunisian Arabic has five types of pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, indirect object, and indefinite pronouns. Unlike in Standard Arabic, there is a unique pronoun for "you" (singular) and a unique pronoun for "you" (plural). Also, there are three types of articles: definite, demonstrative, and possessive articles. Most of them can be written before or after the noun.

As for verbs, they are conjugated in five tenses: perfective (completed action), imperfective (ongoing action), future, imperative (commands), conditional present, and conditional past. They also have four forms: affirmative, exclamative, interrogative (questions), and negative forms. They can be preceded by modal verbs (like "can," "must") to show a certain intention, situation, belief, or duty when they are in perfective or imperfective tenses. Questions in Tunisian Arabic can be āš (wh question, like "what" or "where") or īh/lā (yes–no question, like "yes" or "no").

The question words for āš questions can be either a pronoun or an adverb. For negation, it is usually done using the structure mā verb+š.

There are three types of nouns that can be made from verbs: present participle, past participle, and verbal noun. There are even nouns made from simple verbs that have the root fʿal or faʿlil. The same is true in Standard Arabic. Tunisian Arabic also uses several prepositions (like "in," "on") and conjunctions (like "and," "but"). These structures originally come from Standard Arabic, even if they are very different in modern Tunisian due to strong influence from Berber, Latin, and other European languages.

Meanings and How Language is Used

Conversations in Tunisian Arabic often use metaphors (saying one thing means another). Also, Tunisian Arabic styles and tenses have several hidden meanings. For example, using the past tense can mean that a situation cannot be controlled. Also, using third-person pronouns can figuratively mean saints or supernatural beings. Using demonstratives can have figurative meanings, like showing underestimation. Moreover, the names of some body parts can be used in phrases to get figurative meanings. This is called embodiment.

Some structures, like nouns and verbs, have figurative meanings. Whether these figurative meanings are used depends on the situation of the conversation, such as the country's political situation and the ages of the people talking.

International Influences

Some Tunisian words have been used in famous Arabic songs and poems, like ʿaslāma by Majda Al Roumi. Also, some famous Arabic singers are known for singing old Tunisian Arabic songs, like Hussain Al Jassmi and Dina Hayek. Tunisian Arabic influenced several Berber dialects by giving them Arabic or Tunisian structures and words. It was also the origin of Maltese. Some of its words, like بريك Brīk and فريكساي frīkasāy, were inspired by French as borrowed words. The Tunisian Arabic word Il-Ṭalyānī (الطلياني) meaning "the Italian" was used as the title of a novel in Standard Arabic. This novel won the Booker Prize for Arabic literature in 2015. Also, some famous TV series from other Arabic countries, like the Lebanese Cello Series, included a character speaking Tunisian Arabic.

See also

In Spanish: Árabe tunecino para niños

In Spanish: Árabe tunecino para niños

- Mediterranean Lingua Franca

- African Romance

- Varieties of Arabic

- Maghrebi Arabic

- Maltese language

- Libyan Arabic

- Algerian Arabic

- Moroccan Arabic

- Berber languages

- Punic language

- Phoenician language

|

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |