Uriel da Costa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Uriel da Costa

|

|

|---|---|

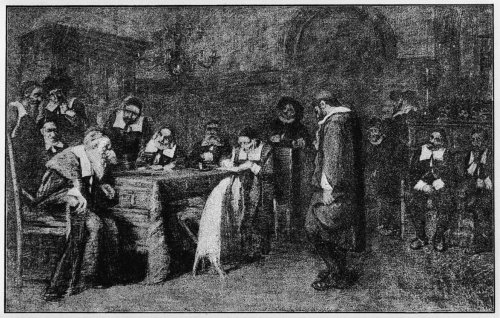

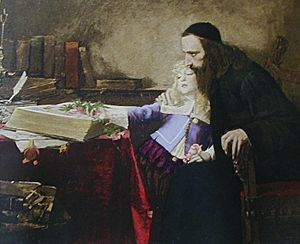

Uriel d'Acosta instructing the young Spinoza (1901) by Samuel Hirszenberg

|

|

| Born | Gabriel da Costa Fiuza 1585 C. |

| Died | 1640 C. |

| Education | Universidade de Coimbra, Faculty of Law (BA, June 1608) |

| Era | 17th century Philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| Institutions | University of Coimbra |

|

Main interests

|

Biblical Criticism, Criticism of Judaism, Philosophy of Religion, ethics, morality |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Uriel da Costa (also known as Acosta or d'Acosta; around 1585 – April 1640) was a Portuguese philosopher. He was born into a family that had converted from Judaism to Catholicism. Later, he chose to return to Judaism. However, he soon began to question the religious rules and leaders of both the Catholic Church and the Jewish faith of his time.

Contents

Uriel da Costa's Early Life

Many details about Uriel da Costa's life come from his short autobiography. Over time, new documents found in Portugal, Amsterdam, and Hamburg have added more to his story.

Costa was born in Porto, Portugal. His birth name was Gabriel da Costa Fiuza. His family were "New Christians." This meant they were Jews who had been forced to convert to Catholicism in 1497 by a government rule. His father was a wealthy international merchant. He also collected taxes for the government.

Gabriel studied church law at the University of Coimbra from 1600 to 1608. During this time, he started reading the Bible very carefully. He also held a position in the church. In his autobiography, Costa said his family were strong Catholics. But they were investigated several times by the Portuguese Inquisition. This suggests they might have been "Conversos" or "Marranos." These were people who secretly kept some Jewish customs. Gabriel openly supported following the rules found in the Torah, the first five books of the Bible.

In 1614, after his father died, his family faced money problems. They secretly left Portugal with a lot of money they had collected as tax-farmers. The family then went to major Sephardic Jewish communities. Gabriel went to Hamburg, Germany. There, he became known as Uriel to his Jewish neighbors. To others, he was Adam Romez, likely because he was wanted in Portugal. The family continued their international trade business.

Questioning Jewish Traditions

When Costa arrived in Hamburg, he quickly became unhappy with the way Judaism was practiced. He felt that the rabbinic leaders focused too much on rituals and strict legal rules.

His first known writing was called Propostas contra a Tradição (Propositions against the Tradition). In this short work, he questioned why some Jewish customs were different from a direct reading of the Law of Moses. He argued that the laws in the Bible were enough. In 1616, he sent this text to the Jewish leaders in Venice. The Venetians disagreed with him. They told the Hamburg community to punish Costa with a herem, which means excommunication. This meant he was officially removed from the Jewish community.

It is not clear how much this excommunication affected his daily life. Costa barely mentions it in his autobiography. He continued his international business. In 1623, he moved to Amsterdam. The Jewish leaders in Amsterdam were worried about a known heretic arriving. They held a hearing and confirmed the excommunication.

His Book and Further Problems

Around the same time, Costa was writing another book. Three chapters of his unfinished book were stolen. They were used by Semuel da Silva of Hamburg to write a quick response. So, Costa made his book longer. The printed version included his answers to Silva's points.

In 1623, Costa published his Portuguese book, Exame das tradições phariseas (Examination of Pharisaic Traditions). This book was over 200 pages long. In the first part, he expanded on his earlier "Propositions." He also considered the responses from Leon of Modena. In the second part, he added his new idea that the Hebrew Bible does not support the idea of the immortality of the soul. Costa believed this idea was not from the original biblical Judaism. He thought it was mainly developed by later Pharisaic rabbis.

The book also pointed out differences between biblical Judaism and Rabbinic Judaism. He said that Rabbinic Judaism had become a collection of mechanical ceremonies. He felt it lacked true spiritual meaning. Costa was one of the first to teach Jewish readers that the soul might not be immortal. He relied only on a direct reading of the Bible. He did not use the writings of rabbis or other philosophers.

This book caused a lot of debate among the local Jewish community. Their leaders told the city authorities that the book attacked both Christianity and Judaism. As a result, the book was publicly burned. Costa also had to pay a large fine.

In 1627, Costa lived in Utrecht. The Amsterdam community still had problems with him. They asked a Venetian rabbi if Costa's elderly mother could be buried in their city. The next year, his mother died, and Uriel returned to Amsterdam.

Eventually, Costa felt very lonely. Around 1633, he agreed to rejoin the community. He did not explain the terms in his autobiography.

Final Humiliation and Death

Soon after rejoining, Costa faced another trial. He met two Christians who wanted to convert to Judaism. Based on his beliefs, he told them not to. Because of this and earlier accusations about kashrut (Jewish dietary laws), he was excommunicated again.

He wrote that he lived in isolation for seven years. His family avoided him, and he had money disputes with them. To get legal help, he decided to pretend to follow traditions again, even if he did not truly believe in them. He wanted to find a way to be accepted.

As punishment for his views, Costa was publicly given 39 lashes at the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam. Then, he was forced to lie on the floor while the people walked over him. This made him feel very sad and angry. He wanted revenge against the relative who had caused his trial seven years earlier.

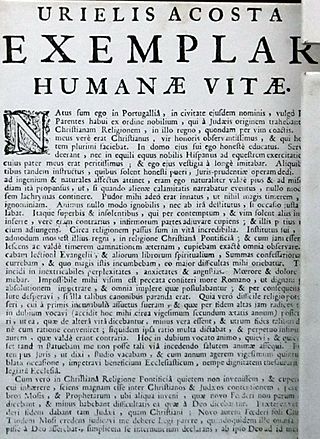

This humiliating event is the dramatic end of his autobiography. This short document was published in Latin after his death. It was titled Exemplar Humanae Vitae (Example of a Human Life). It tells his life story and how his ideas developed. It also shows his experience as a victim of intolerance.

The book also shares his rational and skeptical views. He questioned if biblical law truly came from God or if Moses just wrote it down. He suggested that all religion was created by humans. He specifically rejected formal, ritual-filled religion. He thought religion should be based only on natural law. He believed God did not need empty ceremonies, violence, or conflict.

One day, he saw his relative approaching. He grabbed a pistol and tried to shoot him, but it did not fire. Then, he took another pistol, turned it on himself, and fired. He died a terrible death.

Uriel da Costa's Impact

People have viewed Uriel da Costa in many ways. During his lifetime, his book Examinations led to responses from other thinkers. It was also listed in the Index of Prohibited Books, a list of books forbidden by the Catholic Church.

After his death, his name became linked with his autobiography, Exemplar Humanae Vitae. Later, thinkers like Pierre Bayle wrote about his ideas.

During the Age of Enlightenment, people viewed Costa's ideas about "Rational Religion" more openly. Herder praised him as someone who fought for true belief. Voltaire noted that he left Judaism for philosophy.

Within Judaism, some saw him as a troublesome heretic. Others saw him as a martyr who suffered because of the strictness of the Rabbinic leaders. He is also seen as someone who came before Baruch Spinoza and modern biblical criticism.

Costa's story also shows the challenges many "Marranos" faced when they joined an organized Jewish community. As a Crypto-Jew in Iberia, he read the Bible and was deeply impressed. But when he met an organized Rabbinic community, he was not as impressed by their established rituals and beliefs, like the Oral Law. As da Costa himself pointed out, traditional Pharisee and Rabbinic ideas had been questioned before by the Sadducees and by the Karaites.

Works Based on Costa's Life

- In 1846, the German writer Karl Gutzkow wrote Uriel Acosta. It was a play about Costa's life. This play became the first classic play translated into Yiddish. It was a popular play in Yiddish theater for a long time.

- Osip Mikhailovich Lerner translated the play into Yiddish. He staged it in Odessa, Ukraine, in 1881.

- Abraham Goldfaden quickly followed with his own version, an operetta, in Odessa.

- Israel Rosenberg also made his own translation for a play in Łódź, Poland. This play starred Jacob Adler as Uriel. It remained a key role for Adler throughout his acting career.

- Hermann Jellinek wrote a book called Uriel Acosta in 1848.

- Israel Zangwill used Uriel da Costa's life in his book Dreamers of the Ghetto.

- Agustina Bessa-Luís, a Portuguese writer, published the novel Um Bicho da Terra (An Animal of the Earth) in 1984. It was based on Uriel's life.

- Ariel Magnus, an Argentine writer, published the novel Uriel y Baruch: El alma de la inmortalidad (Uriel and Baruch: The soul of immortality) in 2022. It imagines Uriel da Costa's final moments with a young Spinoza present.

Uriel da Costa's Writings

- Propostas contra a Tradição (Propositions against the Tradition), around 1616. This was a letter to rabbis, arguing against their traditions that were not in the Bible.

- Exame das tradições phariseas (Examination of Pharisaic Traditions), 1623. In this book, Costa argued that the human soul is not immortal.

- Exemplar humanae vitae (Example of a human life), 1640. This is Costa's autobiography. It questions who wrote the Torah and trusts in natural laws.

See also

In Spanish: Uriel da Costa para niños

In Spanish: Uriel da Costa para niños

- Criticism of Judaism

- Criticism of the Talmud

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |