African Americans in Omaha, Nebraska facts for kids

African Americans have played a huge role in making Omaha, Nebraska, the city it is today. The first free Black person settled here in 1854, the same year Omaha became a city.

In 1894, Black residents in Omaha created the first fair in the United States just for African-American artists and visitors. By 2000, over 51,910 African Americans lived in Omaha. That was more than 13% of the city's population!

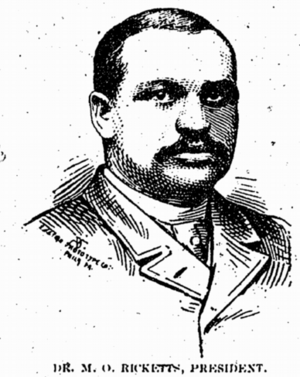

In the 1800s, Omaha was growing fast. It attracted many ambitious people, like Dr. Matthew Ricketts and Silas Robbins. Dr. Ricketts was the first African American to graduate from a Nebraska college. Silas Robbins was the first African American lawyer in Nebraska. In 1892, Dr. Ricketts also became the first African American elected to the Nebraska State Legislature. Later, Ernie Chambers, a barber from North Omaha, became the longest-serving state senator in Nebraska history. He served for over 35 years!

Omaha had many factory jobs, especially with railroads and meatpacking. This made it a popular place for African Americans moving from the South during the Great Migration in the early 1900s. By 1910, Omaha had the third-largest Black population among western cities. From 1910 to 1920, Omaha's African-American population doubled to over 10,000 people. Most of these new residents came from the South.

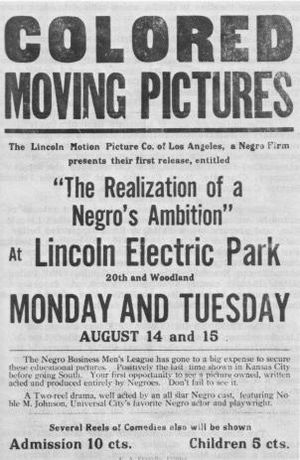

In 1915, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company was started in Omaha. It was the first film company owned by African Americans. Like other big cities, Omaha had a race riot in 1919. This event led to more separation between neighborhoods. But by the 1920s, a lively African-American music and entertainment scene grew in the city.

In the 1930s, rules like redlining made it hard for African Americans to move out of North Omaha. But Black workers joined with others to form the United Meatpacking Workers of America union. This union helped end segregated jobs in the meatpacking industry. It also supported the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s. During this time, activists worked hard to improve life for African Americans in Omaha.

Later, many jobs were lost in the railroad and meatpacking industries. This hit African Americans especially hard. Many moved away for work, and poverty increased in North Omaha. Today, Omaha has one of the highest poverty rates for African Americans among large U.S. cities. Nearly six out of ten Black children in Omaha live below the poverty line.

Contents

Omaha's Growing Black Community

The first Black person recorded in the Omaha area was "York" in 1804. He was a slave with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. More Black people, likely slaves, were seen near Fort Lisa in 1819. They lived at the fort and on nearby farms.

Early Days in the 1800s

After slavery ended in Nebraska, Sally Bayne became the first free Black person to live in Omaha in 1854. In the 1860s, the U.S. Census showed 81 "Negroes" in Nebraska. Most lived in Omaha and Nebraska City.

Some early African-American residents might have come through the Underground Railroad. This secret network helped slaves escape to freedom. One escapee, Henry Daniel Smith, arrived in Nebraska this way.

By 1867, enough Black people lived in Omaha to start St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church. It was the first church for African Americans in Nebraska. The first recorded birth of an African American in Omaha was William Leper in 1872.

At first, African Americans lived all over Omaha. By 1880, there were nearly 800 Black residents. Many were hired by the Union Pacific Railroad. By 1884, three Black churches had been founded. By 1900, there were 3,443 Black residents in Omaha.

Black men and women quickly formed social groups. The Women's Club started in 1895, focusing on education and community improvement. The community also started its own newspapers, like the Progress and The Enterprise.

Black leaders also made a mark in public life. In 1892, Dr. Matthew Ricketts was the first Black person elected to the Nebraska Legislature. In 1895, Silas Robbins became the first Black lawyer in Nebraska.

The 1900s and Growth

In the early 1900s, two Black doctors, Riddle and Madison, opened a hospital for African Americans. In 1912, Omaha started its chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This was the first NAACP chapter west of the Mississippi River.

Railroads and meatpacking companies brought many African-American workers from the South. From 1910 to 1920, Omaha's Black population grew from 4,426 to 10,315. This made up five percent of Omaha's total population. Omaha had the second-largest Black population among western cities by 1920.

This fast growth caused some tension. There were also labor problems and soldiers returning from World War I looking for jobs. In August 1919, a local newspaper reported that many Black workers were arriving in Omaha. This added to the city's tensions. The hiring of Black workers sometimes caused problems in the job market.

From 1910 to the 1950s, Omaha was a major destination for African Americans during the Great Migration. A lively African-American culture grew in the 1920s. By the 1940s, the Black community was strong. It had over a hundred Black-owned businesses, doctors, dentists, and lawyers. More than twenty social groups and clubs were active. Churches were also very important.

Community Areas

Early African-American neighborhoods included Casey's Row. This was a community of homes for Black families, many of whom worked for the Union Pacific Railroad. Omaha's first "Negro district" was at Twentieth and Harney Streets in the 1880s.

The Near North Side, just north of Downtown Omaha, has been home to most African Americans in Omaha for nearly 100 years. This area originally had many European immigrants. Over time, more African Americans moved there. Omaha's cemetery was always integrated, meaning people of all races were buried together.

After the Omaha race riot of 1919, neighborhoods became more separated. During the riot, a Black worker named Will Brown was attacked by a white mob. After the riot, the city started using rules to keep races separate in housing. This meant Black people couldn't easily buy or rent homes outside North Omaha. These rules were made illegal in 1940.

In the 1930s, the government built housing projects for working families. The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project in North Omaha was one of them. It was meant to improve housing for working-class people. Over time, it became home mostly to low-income African Americans. These projects have since been torn down and replaced with new housing that mixes different income levels.

African-American neighborhoods in Omaha have been studied a lot. The movie A Time for Burning showed the opinions of young Ernie Chambers. He later became a lawyer and was elected to the Nebraska Legislature. He served for over 35 years.

Jobs and Achievements

The Union Pacific Railroad first brought many African-American workers to Omaha in 1877. Black barbers in Omaha formed the city's first labor union in 1887. Dr. Stephenson was the first African-American doctor in Omaha, arriving in 1890. Dr. Matthew Ricketts was the first African-American medical student to graduate from the University of Nebraska College of Medicine. He started his practice in North Omaha. In 1892, Dr. Ricketts was the first African American elected to the Nebraska Legislature.

The first African-American fair in the United States happened in Omaha on July 3–4, 1894. Only horses owned by Black people raced, and all exhibits were made or owned by Black people.

African Americans also built and supported a "Colored Old Folks Home" in North Omaha in the 1910s. Clarence W. Wigington was a famous African-American architect from Omaha. He designed St. John's A.M.E. and the Broomfield Rowhouse.

Miss Lucy Gamble was the first African-American teacher in the Omaha Public Schools. She taught from 1899 to 1905. The first film company controlled by Black filmmakers was founded in Omaha in 1915. George and Noble Johnson started the Lincoln Motion Picture Company to make movies for African-American audiences. The company quickly moved to Los Angeles.

Today, African Americans own half of all minority-owned businesses in Omaha.

Politics and Leadership

African Americans in Omaha slowly gained more political power starting in the mid-1900s. More people went to college and became professionals.

In 1892, Dr. Matthew Ricketts became the first African American elected to the Nebraska Legislature. He was a key leader in Omaha's African-American community.

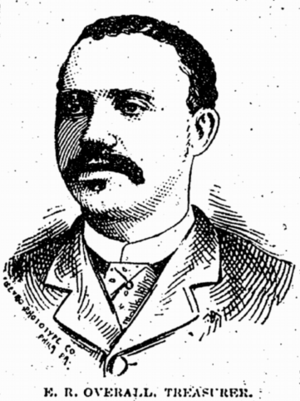

No African Americans served on the Omaha City Council until district elections began. In 1893, Edwin R. Overall, a mail carrier, ran for City Council. He didn't win because elections were city-wide, and white candidates usually won.

In 1981, after City Council elections changed to district representation, Fred Conley became the first African American elected. He served until 1989. In 1992, Carol Woods Harris was the first African American elected to the Douglas County Board.

African Americans have been on the Omaha School Board since 1950. Elizabeth Davis Pittman was the first elected. However, schools remained separated for a long time due to neighborhood boundaries.

Brenda Council, a former school board and city council member, almost became mayor in 1997. In 2003, Thomas Warren, Brenda Council's brother, became Omaha's first African-American Chief of Police.

In 2005, Marlon Polk became the first African American to be a District Court Judge in Nebraska. In 1970, Ernie Chambers became the second African American elected to the state legislature. He has won every election since then and is the longest-serving Nebraska Senator in history.

African-American Firefighters

Hose Company #12 hired the first African-American firefighters in Omaha. One of the first was James C. Greer, Sr., who served from 1906 to 1933. He became a captain.

In 1940, an African-American firefighter was assigned to the city's Fire Prevention office. By the 1950s, Omaha had two companies of African-American firefighters. Omaha's Fire Department became integrated in 1957.

African-American Culture

Churches and Faith

The first African-American churches in Omaha included St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church (1867) and Zion Baptist Church (1888). Future architect Clarence W. Wigington designed Zion's current building.

Salem Baptist Church was very important. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke there in 1957.

Social Clubs and Groups

North Omaha's African-American community had many important social clubs. In the 1930s, there were about 25 clubs with over two thousand members. These groups included the Pleasant Hour Club and the Aloha Club. The North Side YWCA was also very influential. The community also supported the Old Colored Folks' Home, started in 1913.

The Royal Circle was a top African-American social group. It held annual dances for young women. Other groups included the American Legion and the Centralized Commonwealth Civic Club, which helped local businesses. Two Boy Scout troops were founded for African-American youth.

Groups like the Odd Fellows, Masons, and Elks also had halls in North Omaha. The Knights and Daughters of Tabor was a secret group that worked to end slavery.

Entertainment and Music

From the 1920s to the early 1960s, North Omaha had a lively African-American entertainment area. It featured local and national musicians. The most important place was the Dreamland Ballroom, opened in 1923. Dreamland hosted famous jazz, blues, and swing artists like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Louis Armstrong.

The intersection of 24th and Lake Streets was the heart of the city's African-American culture. It had a thriving jazz and rhythm & blues scene. Musicians like Cab Calloway stayed in local homes due to racial segregation. Early North Omaha bands included the Dan Desdunes Band and the Lloyd Hunter Band. Lloyd Hunter's band was the first Omaha band to record music in 1931.

Omaha-born Wynonie Harris, a founder of rock and roll, started in North Omaha clubs. The decline of this scene is often linked to the riots of the 1960s. Today, groups like Love's Jazz & Art Center and the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame celebrate this history.

Famous Musicians

Preston Love, a jazz musician, once said that North Omaha was a "hub for black jazz musicians."

The history of Black music in Omaha is rich. Josiah Waddle formed Omaha's first African-American band in 1902. He also started the first women's band in Omaha in 1917. One of his students was Lloyd Hunter, who led a very popular orchestra. Anna Mae Winburn also studied with Waddle. She later led the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, the first integrated all-women's band in the U.S.

International jazz legend Preston Love was a key figure. After playing with Count Basie, Love returned to North Omaha and started his own band. He also worked for the Omaha Star newspaper.

North Omaha's music scene produced many influential Black musicians. Rhythm & Blues singer Wynonie Harris and drummer Buddy Miles (who played with Jimi Hendrix) grew up and played together in Omaha. Big Joe Williams and funk band leader Lester Abrams are also from North Omaha.

Historic Newspapers

Omaha has had many African-American newspapers. The first was the Progress, started in 1889 by Ferdinand L. Barnett. Cyrus D. Bell started the Afro-American Sentinel in 1892. The Enterprise, started by George F. Franklin, was the longest-running early Black newspaper in Omaha. The Omaha Monitor, started in 1915 by Reverend John Albert Williams, was also very popular.

Today, African-American culture in Omaha is strongly connected to The Omaha Star. It was founded by Mildred Brown and her husband in 1938. Mildred Brown is believed to be the first African-American woman to found a newspaper in the nation. She managed the paper for her whole life. Since 1945, it has been the only Black newspaper printed in Nebraska.

Other Cultural Places

The Fair Deal Cafe on North 24th Street was called the "Black City Hall" from 1954 to 2003. Today, Omaha's African-American community celebrates its heritage in many ways. The Native Omaha Days is a week-long celebration with picnics, family reunions, and a big parade. The Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame also honors Black musicians and cultural leaders.

The Great Plains Black History Museum opened in North Omaha in 1974. It holds Omaha's only African-American history collection. The annual Omaha Jazz and Blues Festival also promotes African-American culture.

Race Relations in Omaha

North Omaha has a difficult history of race relations. In 1891, an African American man named George Smith was attacked at the Douglas County Courthouse.

In July 1910, racial tension increased after Black boxer Jack Johnson won a big fight. White mobs rioted in Omaha, hurting several Black men and killing one.

In 1919, a local newspaper published stories that increased racial tensions. During the Omaha race riot of 1919 in September, a white mob attacked the Douglas County Courthouse. They attacked Willy Brown, a Black worker. Soldiers from Fort Omaha had to stop the riot.

Segregation and Its Impact

After this terrible summer, many of Omaha's neighborhoods became separated by race. In the 1930s, banks used redlining and housing rules to keep African Americans from buying or renting homes outside North Omaha.

The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project, built in the 1930s, was meant to improve housing for working-class people. But for decades, it was closed to African Americans. Even in the 1940s, Black families couldn't find housing elsewhere. In the 1960s, civil rights efforts changed these rules.

Over time, these projects became home mostly to unemployed people. In the 1990s, the city decided to tear down the Logan Fontenelle Housing Project. Today, public housing in Omaha is spread out and often mixed with other types of housing.

The Civil Rights Movement

The attack on Willy Brown helped push Omaha's African-American community to fight for change. In the 1920s, the Omaha chapter of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association was founded by Earl Little, the father of Malcolm X. Malcolm X was born in Omaha in 1925. His mother said their family was warned to leave Omaha by the Ku Klux Klan because her husband was "stirring up trouble." The family moved soon after.

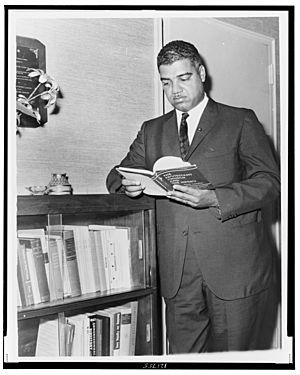

In 1920, the Colored Commercial Club was formed to help Black people in Omaha find jobs and start businesses. The National Federation of Colored Women had five chapters in Omaha. In 1927, the first Urban League chapter in the American West was founded in Omaha. Whitney Young led the chapter in 1950, greatly increasing its members. He later became the national leader of the Urban League.

In the 1930s, a group of Black and white workers successfully formed the United Packinghouse Workers of America union. They worked to end job segregation in meatpacking in the 1940s. Community leader Rowena Moore fought for more opportunities for Black women in industry. This union helped African Americans gain political power and end segregation in stores in the 1950s. However, many jobs were lost in the 1960s, which hurt working-class communities.

In 1952, Arthur B. McCaw became the first African American to hold a high-level position in the Nebraska governor's office. He was the state's budget director.

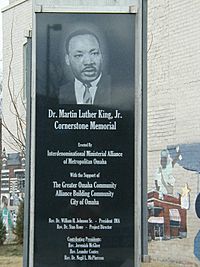

Omaha was visited by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1958 and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968. Their visits helped inspire the Civil Rights Movement in North Omaha. Local leaders continued to fight against racism.

Integration Efforts

Starting in the 1950s, many white middle-class families moved from North Omaha to the suburbs. This was called "white flight." This made it harder to solve problems in Omaha's African-American community. Schools were also affected.

After a 1971 court ruling about school integration, Omaha tried to integrate its schools. However, studies showed that school boundaries and new school locations still led to separation. White student enrollment in Omaha Public Schools dropped in the 1970s, while Black student enrollment increased. In the 1990s, the Omaha Housing Authority changed its housing plan, tearing down some large housing projects.

Race Riots and Their Aftermath

The Civil Rights Movement brought calls for Black power and an end to racism in Omaha. Young people were being sent to fight in the Vietnam War, but funding for education and youth programs was cut. Police actions also targeted African-American youth. This led to a series of protests and riots.

On July 4, 1966, a crowd of African Americans gathered at North 24th and Lake Streets. When police asked them to leave, violence broke out. The crowd damaged police cars and businesses along North 24th Street. After three days, there was millions of dollars in damage.

More riots happened on August 1, 1966, after a 19-year-old was shot by an off-duty policeman. Three buildings were firebombed, and many police were needed to stop the crowds.

On March 4, 1968, high school and college students protested a politician's campaign at the Omaha Civic Auditorium. Violence broke out, and an African-American youth was shot and killed by a police officer. The next day, local barber Ernie Chambers helped calm students and prevent another riot.

On June 24, 1969, African-American teenager Vivian Strong was shot and killed by police at the Logan Fontenelle Housing Project. Young African Americans in the area rioted in response. Businesses along North 24th Street were damaged. This was the last major riot noted in Omaha.

The effects of these riots can still be seen on North 24th Street, with many empty lots and economic problems.

Honoring History

Several groups have been formed to remember the history of African Americans in Omaha. In the 1960s, Bertha Calloway founded the Nebraska Negro Historical Society. In 1974, the Society opened the Great Plains Black History Museum.

In 1976, the community started Native Omaha Days, a celebration of Black history in the city. Rowena Moore helped recognize the Malcolm X House Site in the 1970s. A monument to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was placed on North 24th Street in the late 1990s. The Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame was founded in 2005 to celebrate the city's musical history.

Economic Challenges

In 2007, a poverty group director said, "In Omaha, you start talking about low-income issues, people assume you're talking about minority issues..." Omaha has one of the highest percentages of low-income African Americans in the country. Census data from 2000 showed that over 7,800 families in Douglas County lived below the poverty line. Nearly six out of ten Black children in Omaha live in poverty. Only one other major U.S. city, Minneapolis, has a bigger economic gap between Black and white residents.

Famous African Americans from Omaha

Malcolm X once said, "Being born in Omaha doesn't make me an American any more than being born in an oven makes a cat a biscuit."

| Notable African Americans from Omaha (alphabetical) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Image | Role | Era |

| Dinah Abrahamson | Author, politician | 2010s | |

| Lester Abrams | Funk musician | 1970s | |

| John Adams, Jr. | Lawyer, state legislator | 1930s–1940s | |

| John Adams, Sr. | Lawyer, minister, state legislator | 1920s–1960s | |

| Houston Alexander | Mixed martial artist, hip hop artist, radio DJ | 1980s-present | |

| Comfort Baker | First African American to graduate from Omaha High Schools | 1890s | |

| Alfred S. Barnett | Journalist | 1880s–1890s | |

| Ferdinand L. Barnett | Journalist, founder of The Progress, state legislator | 1880s–1931 | |

| John Beasley | Television and film actor | 1980s–present | |

| Cyrus D. Bell | Politician, journalist, founder of The Afro-American Sentinel | 1860s-1910s | |

| Bob Boozer | Former National Basketball Association player, Olympic gold medalist | 1950s–1960s | |

| Frank Brown | City of Omaha City councilmember | 1970s–present | |

| Mildred Brown | Founder of the Omaha Star newspaper | 1930s–1980s | |

| Willy Brown | Local worker attacked by white mob | 1919 | |

| James Bryant | Journalist | 1890s | |

| Herman Cain | Former CEO of Godfather's Pizza, Federal Reserve Bank chairman, political candidate | 1980s–1990s | |

| Bertha Calloway | Founder of the Great Plains Black History Museum | 1960s–1990s | |

| Ernie Chambers | Longest-serving Nebraska State Senator in history | 1960s–present | |

| Emanuel S. Clenlans | Postal clerk | 1870s–1910s | |

| Ophelia Clenlans | Journalist | 1890s–1900s | |

| Brenda Council | City of Omaha councilmember, school board member | 1970s–present | |

| Alfonza W. Davis | Captain in the Tuskegee Airmen, first Black military aviator from Omaha | 1940s | |

| Dan Desdunes | Musician, civil rights activist | 1890s–1920s | |

| Rodolphe Desdunes | Poet, historian, civil rights activist | 1870s–1920s | |

| Lucille Skaggs Edwards | Journalist, politician | 1900s–1930s | |

| George F. Franklin | Journalist, founder of The Enterprise | 1890s | |

| Lucy Gamble | First African American schoolteacher in Omaha | 1890s-1950s | |

| William R. Gamble | Barber | 1870s–1890s | |

| Bob Gibson | Baseball Hall of Fame pitcher | 1950s–1980s | |

| Ahman Green | Professional football player | 1990s – 2000s | |

| Wynonie Harris | Rhythm and blues singer | 1960s–present | |

| Harry Haywood | High-profile international Communist Party leader | 1940s-1970s | |

| Cathy Hughes | Founder and president of Radio One | 1970s-present | |

| Lloyd Hunter | Big band leader | 1920s-1950s | |

| Kenton Keith | Professional football player | 1990s-present | |

| Mondo we Langa (aka David Rice) | Poet, playwright, journalist | 1960s-2010s | |

| John Lewis | Hotel keeper, musician | 1870s-1880s | |

| Preston Love | Jazz player | 1950s-1990s | |

| Ella Mahammitt | Journalist, club founder | 1890s | |

| Sarah Helen Mahammitt | Caterer, writer | 1900s-1950s | |

| Thomas P. Mahammitt | Caterer, journalist, newspaper owner | 1890s-1940s | |

| Arthur B. McCaw | Civil Servant, NAACP state chairman, first Black person in a Nebraska governor's cabinet | 1940s-1950s | |

| Aaron Manasses McMillan | Doctor, missionary, state legislator | 1920s-1960s | |

| Lois "Lady Mac" McMorris | Guitarist | 1970s-present | |

| Buddy Miles | Musician | 1960s-1990s | |

| Rowena Moore | Labor activist; founder of the Malcolm X House Site | 1940s-1980s | |

| Sandra Organ | Longtime Houston Ballet soloist | 1980s-present | |

| Edwin R. Overall | Abolitionist, mail carrier, politician | 1850s-1890s | |

| Johnny Owen | State legislator, nicknamed "Negro Mayor of Omaha" | 1930s-1950s | |

| George Wells Parker | Co-founder of the Hamitic League of the World | 1910s-1930s | |

| John Grant Pegg | Inspector of Weights and Measures | 1900s-1910s | |

| Harrison J. Pinkett | Journalist, lawyer, soldier | 1900s-1950s | |

| Ed Poindexter | Community activist, writer | 1960s-present | |

| Dr. Catherine Grace Pope, Ed.D. | First African-American to win a title in the Miss America Pageant | 1969 | |

| Ron Prince | Head football coach at Kansas State University | 1980s-2000s | |

| Billy Rich | Musician, bassist for Taj Mahal | 1960s-present | |

| Dr. Matthew Ricketts | First African American elected to the Nebraska Legislature | 1880s-1900 | |

| Silas Robbins | Lawyer, politician | 1880s-1910s | |

| Johnny Rodgers | 1972 Heisman Trophy winner, College Football Hall of Fame Inductee | 1960s-1980 | |

| Joe Rogers | Colorado Lieutenant Governor | 1990s | |

| Amber Ruffin | Comedian, writer and actress | 1990s- | |

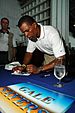

| Gale Sayers | Professional football player, Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee | 1960s | |

| John Andrew Singleton | Dentist, state legislator, civil rights activist | 1920s-1940s | |

| Millard F. Singleton | Civil servant | 1880s-1910s | |

| Walter J. Singleton | Journalist, clerk | 1890s-1930s | |

| W. H. C. Stephenson | Doctor, preacher, first African American doctor in Nevada | 1860s-1890s | |

| Gabrielle Union | Television and film actress | 1990s – 2000s | |

| Luigi Waites | Musician | 1960s–2010 | |

| Victor B. Walker | Soldier, political activist, lawyer, police officer, journalist | 1890s-1920s | |

| Clarence W. Wigington | Architect | 1910s-1950 | |

| Big Joe Williams | Musician | 1930s-1970s | |

| John Albert Williams | Preacher, journalist, published The Monitor | 1890s-1930s | |

| Alphonso Wilson | Politician | 1890s-1910s | |

| Anna Mae Winburn | Big band leader | 1930s–1960 | |

| Helen Jones Woods | Big band trombonist | 1930s–1960 | |

| Malcolm X | Civil rights leader | 1930s–1960s | |

| Whitney Young | Former head of Omaha Urban League | 1930s–1960s | |

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |