Agriculture on the prehistoric Great Plains facts for kids

Long ago, Native American people living on the Great Plains in what is now the United States and southern Canada were skilled farmers. This was before many European explorers arrived, mostly before 1750. Their main crops were maize (corn), beans, and squash, including pumpkins. They also grew sunflowers, goosefoot, tobacco, gourds, and plums.

Archaeologists have found proof of farming in many places across the Central Plains. Sites in Nebraska show crops like little barley, sunflowers, goosefoot, marsh elder, and corn. Tribes sometimes switched between farming and hunting throughout their history, especially during the Plains Village period (AD 950–1850).

Contents

The Great Plains Environment

Growing crops on the Great Plains was often challenging because there wasn't always enough rain for corn, which was their most important crop. Also, in the northern parts of the Great Plains, the growing season was quite short. Farming on the Plains seemed to change over time. During wet periods, farming spread westward into drier areas. But when it got drier, people farmed less.

The number of bison (buffalo) also played a big role in where people settled. Bison were a vital food source for Plains people. They also provided skins for clothes and shelters.

Some experts used to think that the Plains cultures were not as advanced as those in the eastern woodlands or the American Southwest. However, in the late prehistoric and early historic times (around 1400 to 1750 AD), many people moved to the Plains from both the east and the west.

Early Farming History

Native Americans have been gathering wild plants for food on the Great Plains for over 13,000 years. They collected plants like the prairie turnip and chokecherry. Over time, they learned to grow or help grow useful native plants. Many plants grown by Indians in the Eastern Agricultural Complex were also grown on the Great Plains.

Squash and beans were grown in what is now the United States, separate from how they were grown in Mexico. Corn, however, came from Mexico. It traveled northward to the United States over thousands of years. Corn farming began on the Great Plains around 900 AD. This started the Southern Plains villagers period in western Oklahoma and Texas. It likely spread from the Caddoan cultures in eastern Texas.

The Plains Village culture included small settlements and villages along major rivers like the Red, Washita, and Canadian. People got food by both farming and hunting. A drier climate starting around 1000 or 1100 AD might have made them rely more on hunting and less on farming. The Antelope Creek phase (1200 to 1450 AD) in the Texas panhandle was influenced by the Pueblo people from the Rio Grande valley in New Mexico.

The Apishapa culture in southeastern Colorado at the same time mostly relied on hunting. The Wichita and Pawnee Indians are likely descendants of these Southern Plains villagers.

The earliest known dates for corn farming on the northern Great Plains are from 1000 to 1200 AD. The Missouri River Valley in North Dakota was probably the northernmost place where corn was grown before Europeans arrived. Before farming, Native Americans had to develop types of corn that could grow in short seasons. There is no proof of corn farming north of the US-Canada border on the Great Plains before Europeans. But by the 1790s, Native Americans were growing corn as far north as the mouth of the Red River near Winnipeg, Manitoba.

When European explorers first arrived, the main Native American groups who farmed a lot on the Great Plains were:

- Caddoan people along the Red River.

- Wichita people along the Arkansas River.

- Pawnee in the Kansas River and Platte River areas.

- Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa along the Missouri River in the Dakotas.

Other groups moved to the Great Plains later. Some, like the Sioux and Cheyenne, stopped farming to become nomadic hunters. Others, like the Dhegiha (the Osage, Kaw, Omaha, and Ponca) and the Chiwere (the Otoe, Iowa, and Missouria), continued to farm while also hunting buffalo.

Archaeologists have found proof that Apache people (the Dismal River culture) farmed in western Kansas and Nebraska in the 1600s. These semi-nomadic Apache were later pushed south by the fully nomadic Comanche in the 1700s.

Farming Methods and Harvests

Native American farmers on the Great Plains did not have iron tools or animals to pull plows. So, they mainly cleared and farmed wooded land along rivers. They especially liked the lighter soils on raised river terraces, which were naturally fertilized by floods. They avoided the heavy soils of the open prairie, which had thick, tangled roots.

Corn was very productive compared to European grains like wheat. This meant Native American farmers could grow large crops with less effort, using simple tools and small plots of land. However, farming on the Great Plains was always risky due to droughts. While wheat in medieval Europe might yield 2 to 10 seeds for every one planted, corn could yield as many as 100 seeds for every one planted!

An average family farm plot might have been about 0.6 acres. This could produce 10-20 bushels (627 - 1,254 kg) of shelled corn per acre. This was enough to provide about 20% of the food needed for a family of five, even after losing some to pests or spoilage. Some families might have farmed up to 3.4 acres, which would produce enough corn for their family plus extra to trade. New land could yield even more, up to 40 bushels (2,508 kg) per acre. But the soil would become less fertile in later years.

Among the Hidatsa, a typical Plains farming group, fields were cleared by burning, which also helped fertilize the soil. Native American farmers used three main tools: the digging stick, hoe, and rake.

- The digging stick was a sharpened, fire-hardened stick, about three feet long. It was used to loosen soil, pull out weeds, and make holes for planting.

- The hoe was made from a buffalo or elk shoulder blade bone, tied to a wooden handle.

- The rake was made from wood or an antler.

Some Native American women preferred the bone hoe even after iron hoes were brought by European traders.

Sunflowers were the first crop planted in spring. They were planted in groups around the edges of fields. Corn was planted next. Native American planting methods are sometimes called Three Sisters agriculture. About five corn seeds were planted in a small mound of soil. These mounds were spaced about five feet apart. When the corn plants were a few inches tall, climbing beans and squash seeds were planted between the mounds. The large squash leaves shaded the soil, keeping it moist and stopping weeds from growing. The beans added nitrogen to the soil and climbed up the corn stalks for support.

The Wichita, and possibly other southern groups, planted or cared for thickets of low-growing Chickasaw Plum trees. These trees separated and bordered their corn fields. Tobacco was planted in separate fields and cared for by older men. Women did most of the other farming, though men helped clear the land.

Native American farmers did not use animal manure to fertilize their fields. As the soil became less fertile, they would leave fields empty for two years to let the soil recover before planting again.

The Farming Year

The Pawnee in Nebraska were among the best Plains Indian farmers. They had special ceremonies for planting and harvesting corn. In spring, they planted 10 types of corn, seven types of pumpkins and squashes, and eight types of beans. Their corn included flour corn, flint corn, and sweet corn. They also had one very old type of corn grown only for use in their "sacred bundles." The Pawnee knew that different types of corn could mix if grown too close. So, they planted different types in fields far apart.

One Pawnee ceremony during spring planting was the Morning Star ceremony. This ritual was meant to ensure the soil was fertile. The last time this ceremony included a human sacrifice was in 1838.

Like many other Plains farmers, the Pawnee left their villages in late June when their corn was about knee-high. They would live in tipis and go on a summer buffalo hunt. They returned around September 1st to harvest their crops. Corn, beans, and pumpkins were dried, put into rawhide bags, and stored in bell-shaped pits dug underground. After the harvest, the Pawnee had a month of celebrations. In early December, they left their villages again for a winter hunt, with their stored food hidden underground. This yearly cycle was common among Plains farmers, especially after they got horses in the late 1600s and 1700s. Horses allowed them to travel far from their villages for long hunts.

Trade Among Tribes

Trade between farming tribes and nomadic hunting tribes was very important on the Great Plains. The Mandan and Hidatsa villages on the Missouri River in the Dakotas traded a lot with non-farming hunting tribes. In fall 1737, the French explorer La Vérendrye met a group of Assiniboine people. They were planning their yearly two-month, thousand-mile trip south to the Mandan villages. They wanted to trade bison meat for farm goods. This trading trip was done on foot with dogs carrying goods, as neither the Assiniboine nor the Mandans had horses yet. There is much evidence of similar long-distance trading between farmers and hunters among other Plains tribes.

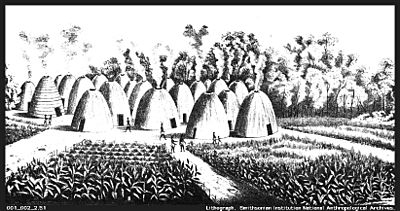

Gallery

See also

In Spanish: Agricultura prehistórica en las Grandes Llanuras para niños

In Spanish: Agricultura prehistórica en las Grandes Llanuras para niños