Beilby Porteus facts for kids

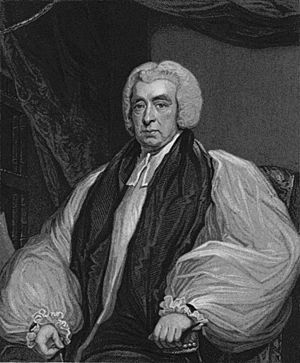

Quick facts for kids The Right Reverend and Right Honourable Beilby Porteus |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of London | |

|

|

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Diocese of London |

| Elected | 1787 |

| Reign ended | 1809 (death) |

| Predecessor | Robert Lowth |

| Successor | John Randolph |

| Other posts | Bishop of Chester 1776–1787 |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1757 (priest) |

| Consecration | 1777 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 8 May 1731 York, Great Britain |

| Died | 13 May 1809 (aged 78) Fulham Palace, London |

| Buried | St Mary's Church, Sundridge |

| Nationality | British |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Residence | Fulham Palace, London |

| Alma mater | Christ's College, Cambridge |

Beilby Porteus (born May 8, 1731 – died May 13, 1809) was an important leader in the Church of England. He served as a bishop and later as the Bishop of London. He was a key figure in reforming the church and was a strong supporter of the movement to end slavery in England. He was one of the first high-ranking church officials to speak out against the Church's involvement in slavery.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Beilby Porteus was born in York, England, on May 8, 1731. He was the youngest of 19 children! His parents, Elizabeth Jennings and Robert Porteus, were planters from Virginia who had moved back to England.

He went to school in York and at Ripon Grammar School. Later, he studied classics at Christ's College at the University of Cambridge. He became a fellow there in 1752. In 1759, he won a special award called the Seatonian Prize for his poem, Death: A Poetical Essay. People still remember him for this poem today.

He became a priest in 1757. In 1762, he started working as a personal assistant to Thomas Secker, who was the Archbishop of Canterbury. During this time, he learned more about the terrible conditions of enslaved Africans in the American colonies and the West Indies. He talked with other clergy and missionaries, getting reports about the suffering of enslaved people from people like Revd James Ramsay and Granville Sharp.

In 1769, Beilby Porteus became a chaplain to King George III. He also served as the Rector of Lambeth from 1767 to 1777.

Porteus was worried that some people in the Church of England were changing the true meaning of the Bible. He believed in keeping Christian teachings pure. However, he was also happy to work with Methodists and other Christian groups. He recognized their important work in spreading Christianity and helping with education.

He was married to Margaret Hodgson. They did not have any children.

Bishop of Chester

In 1776, Porteus was chosen to be the Bishop of Chester. He started this new role in 1777. He quickly began to address the challenges in his new area. This region had a fast-growing population due to the Industrial Revolution, but not enough churches.

He saw the extreme poverty and hardship faced by workers in the new factories. This put a huge strain on church resources. He also continued to care deeply about the enslaved people in the West Indies. He preached and actively campaigned against the slave trade. He took part in many debates in the House of Lords, becoming known as a strong supporter of ending slavery.

He was especially interested in the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. This society owned plantations in Barbados called the Codrington Plantations, where about 300 enslaved people lived.

Porteus was known as a smart scholar and a popular preacher. In 1783, he became nationally famous for giving his most important sermon.

Speaking Out Against Slavery

In 1783, Porteus was invited to give a special sermon for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. He used this chance to criticize the Church of England. He pointed out that the Church was ignoring the suffering of 350 enslaved people on its own Codrington Plantations in Barbados. He suggested ways to improve their lives.

His sermon was a powerful and well-reasoned plea for The Civilisation, Improvement and Conversion of the Negroe Slaves in the British West-India Islands Recommended. He gave this sermon at St Mary-le-Bow church to 40 members of the society, including eleven other bishops. When his words didn't lead to much change, Porteus created a Plan for the Effectual Conversion of the Slaves of the Codrington Estate. He presented this plan to the society's committee in 1784 and again in 1789. He was very disappointed when his plan was rejected by the other bishops.

These were the first steps in his 26-year fight to end slavery in the British West Indian colonies. Porteus made a huge difference. He also wrote, encouraged political actions, and supported sending missionaries to Barbados and Jamaica. He became a very dedicated and passionate abolitionist, the most senior church leader of his time to actively fight against slavery.

He joined a group of abolitionists in Kent, led by Sir Charles Middleton. Soon, he met other important activists like William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Henry Thornton, and Zachary Macaulay. Many of these people were part of the Clapham Sect, a group of Christian social reformers. Porteus gladly supported them and their campaigns.

As William Wilberforce repeatedly tried to pass a law to end the slave trade in the British parliament over 18 years, Porteus strongly supported the campaign. He worked hard within the Church of England and among the bishops in the House of Lords.

Bishop of London

In 1787, Porteus became the Bishop of London. He held this important position until his death in 1809. As Bishop of London, he also became a member of the Privy Council and the Dean of the Chapel Royal. In 1788, he supported Sir William Dolben's Slave Trade Bill. For the next 25 years, he was the main supporter within the Church of England for ending slavery. He helped people like Wilberforce, Granville Sharp, and Zachary Macaulay to ensure the Slave Trade Act was passed in 1807.

Because of his strong involvement in the anti-slavery movement, it made sense that as Bishop of London, he was now officially responsible for the spiritual well-being of the British colonies overseas. He was in charge of missions to the West Indies and India. Towards the end of his life, he personally paid to send Bibles in different languages to places as far away as Greenland and India.

Porteus was a man of strong moral beliefs. He was also very concerned about what he saw as a decline in morals in the country during the 18th century. He campaigned against things like pleasure gardens and theatres, and against people not observing Sunday as a day of rest. He strongly opposed the ideas of the French Revolution and the teachings of Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason. In 1793, Porteus suggested that Hannah More write Village Politics, a short pamphlet to counter Paine's ideas. This was the first of many popular writings designed to fight against what they saw as the bad morals of the time.

Other Important Work

For much of the next 20 years, a time of big changes in the country and the world, Porteus was able to influence important people. These included those at the Court, in the government, in the City of London, and in high society.

Porteus did this by encouraging discussions on many topics. These included the slave trade, the rights of Catholics, and the pay for low-paid clergy. He also spoke out against too much entertainment on Sundays. He became a vocal supporter of William Wilberforce, Hannah More, and the Clapham Sect of Christian social reformers. He also helped set up Sunday Schools in every church area. He was an early supporter of the Church Missionary Society and one of the founders of the British and Foreign Bible Society.

He was a well-known supporter of people reading the Bible for themselves. He even had a system of daily Bible readings named after him, called the Porteusian Bible, which was published after he died. He also helped introduce the use of short writings called tracts by church groups. Even though he was a strong Church of England man, Porteus was happy to work with Methodists and other Christian groups, recognizing their important contributions.

In 1788, George III became ill again. The next year, a special service was held at St Paul's Cathedral to give thanks for his recovery, and Porteus himself preached there.

The war against Napoleon began in 1794 and lasted for 20 years. During Porteus's time as Bishop of London, there were services to celebrate British victories in battles like Cape St. Vincent, the Nile, and Copenhagen. There was also great sadness when Nelson died in 1805, followed by his large state funeral in St Paul's Cathedral in 1806.

After his health slowly declined for three years, Bishop Porteus died at Fulham Palace in 1809. As he wished, he was buried at St Mary's church in Sundridge, Kent. This was close to his country home, where he loved to go every autumn.

Legacy

Beilby Porteus was one of the most important, though often overlooked, church figures of the 18th century. His sermons continued to be read by many people. His work as a leading abolitionist was so well known in the early 1800s that his name was almost as famous as William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson. However, 100 years later, he became one of the "forgotten abolitionists." Today, his role is often ignored, and his name is mostly found in historical footnotes. His main fame in the 21st century is for his poem Death. Some people also unfairly think he was the inspiration for the proud Mr. Collins in Jane Austen's novel Pride and Prejudice.

It's interesting that Porteus's most lasting contribution is one he's not well known for: the Sunday Observance Act of 1781. He created this law because he was concerned about the moral decline in England. This law controlled how people could spend their free time on weekends for the next 200 years, until the Sunday Trading Act of 1994 was passed.

His legacy continues today because the campaign he helped start eventually changed the Church of England. It became an international movement focused on mission and social justice. Now, it appoints bishops and archbishops from many different ethnic groups, including African, Indian, and Afro-Caribbean leaders.

Works

- Death: A Poetical Essay (1759)

- A Review of the Life and Character of Archbishop Secker (1770)

- On a Life of Dissipation (1770)

- Sermons on Several Subjects (1784)

- An Essay on the Transfiguration of Christ (1788)

- The Beneficial Effects of Christianity on the Temporal Concerns of Mankind, Proved from History and from Facts (1806)

- A Letter to the Governors, Legislatures, and Proprietors of Plantations in the British West-India Islands (1808)

- Heureux effets du Christianisme sur la félicité temporelle du genre humain (1808)

- (editor), The Works of Thomas Secker, LL.D. Late Lord Archbishop of Canterbury (1811 edition)

- volume one

- volume two

- volume three

- Lectures on the Gospel of St. Matthew Delivered in the Parish Church of St. James, Westminster, in the Years 1798, 1799, 1800, and 1801 (1823 edition)

- A Summary of the Principal Evidences for the Truth and Divine Origin of the Christian Revelation (1850 edition by James Boyd)

See also

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |