Montesquieu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Montesquieu

|

|

|---|---|

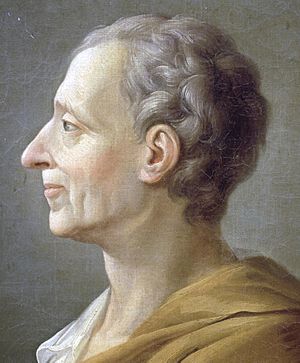

Portrait by an anonymous artist, 1753–1794

|

|

| Born | 18 January 1689 |

| Died | 10 February 1755 (aged 66) Paris, France

|

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Enlightenment Classical liberalism |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Separation of state powers: executive, legislative, judicial; classification of systems of government based on their principles |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (born January 18, 1689 – died February 10, 1755), known simply as Montesquieu, was an important French thinker, writer, and judge. He is famous for his ideas about how governments should be set up.

He is best known for developing the idea of the separation of powers. This means dividing government into different parts so no single part becomes too strong. This idea is now used in many countries' rulebooks, called constitutions. His book, The Spirit of Law (published in 1748), was very popular in Great Britain and the American colonies. It greatly influenced the people who wrote the U.S. Constitution.

Contents

Montesquieu's Life Story

Montesquieu was born at the Château de la Brède in southwest France. This was about 25 kilometers (15 miles) south of the city of Bordeaux. His father, Jacques de Secondat, came from a long line of nobles. His mother, Marie Françoise de Pesnel, died when Charles was only seven years old. She left him the title of Baron of La Brède.

After his mother's death, he went to the Catholic College of Juilly. This was a well-known school for children of noble families in France. He studied there from 1700 to 1711. In 1713, his father passed away. Charles then became the responsibility of his uncle, the Baron de Montesquieu.

In 1714, he became a counselor in the Bordeaux Parlement (which was like a high court). He married Jeanne de Lartigue in 1715, and they had three children. When his uncle died in 1716, Charles inherited his fortune, his title, and his important job as a judge in the Bordeaux Parlement. He held this job for twelve years.

Montesquieu grew up during a time of big changes in government. England had become a constitutional monarchy after its Glorious Revolution in 1688–1689. This meant the king's power was limited by laws. In France, King Louis XIV died in 1715, and a young boy, Louis XV, became king. These changes in England and France greatly influenced Montesquieu's thinking and his writings.

Montesquieu eventually left his law career to focus on studying and writing. He became famous in 1721 with his book Persian Letters. This book was a satire, which means it used humor and exaggeration to criticize French society. It told the story of two visitors from Persia who observed and commented on the strange customs of Paris. The book was an instant hit.

In 1728, Montesquieu traveled across Europe, keeping a detailed journal. He visited Austria, Hungary, and Italy for a year. He spent a year and a half in England, from late 1729 to spring 1731. His travels helped him learn about different laws and customs. These observations became key ideas in his later books about how governments work.

His next important book was Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline (1734). But his most famous work was The Spirit of Law, published in 1748. This book quickly became very important in Europe and America. However, the Catholic Church banned it in 1751, putting it on their list of forbidden books. Despite this, it was highly praised in other parts of Europe, especially in Britain.

Montesquieu was seen as a champion of freedom in the British colonies in North America. Many American leaders, like James Madison, who helped write the U.S. Constitution, were greatly influenced by Montesquieu. His idea that "government should be set up so that no man need be afraid of another" helped shape the U.S. Constitution's system of checks and balances. This system ensures that no single part of the government has too much power.

Towards the end of his life, Montesquieu had trouble with his eyesight. He died in Paris on February 10, 1755, after a high fever.

Montesquieu's Ideas on History

Montesquieu believed that big historical events were not just caused by a few powerful people. He thought that deeper reasons and general human nature played a bigger role.

For example, when the Roman Republic changed into the Roman Empire, he suggested that it wasn't just because of leaders like Caesar or Pompey. He believed that if those specific people hadn't been there, others would have risen to make similar changes. He felt that the desire for power, common to many people, was the real cause.

Montesquieu's Political Ideas

Montesquieu was one of the first thinkers to compare different human societies and their political systems. He looked at how different parts of society work together. This made him a pioneer in the study of human cultures and societies, known as anthropology.

His most famous idea is the separation of powers. He believed that a government should have three main parts, or "powers":

- The executive power: This part carries out the laws (like a president or prime minister).

- The legislative power: This part makes the laws (like a parliament or congress).

- The judicial power: This part interprets the laws and makes sure they are fair (like courts and judges).

Montesquieu argued that these three powers should be separate and independent. This way, no single part could become too powerful and control the others. This idea was very new because it challenged the old system in France, where the king had almost all the power.

He also described three main types of government, each based on a different feeling or "principle":

- Monarchies: These are free governments led by a king or queen. They rely on the principle of honor.

- Republics: These are free governments led by elected officials. They rely on the principle of virtue (meaning people doing what is good for society).

- Despotisms: These are governments where one person has total, unlimited power, like a dictator. They rely on fear.

Montesquieu believed that free governments, like republics and monarchies, were delicate. They needed careful rules to keep liberty safe. He admired England's government because it had a good balance of power. He worried that in France, the power of the king was growing too much, weakening the groups that could limit his power.

Montesquieu also wrote about slavery in The Spirit of Law. He argued that slavery was wrong because all people are born equal. He even used a clever, sarcastic list of arguments that people used to support slavery, to show how ridiculous they were. For example, he mentioned that some people argued sugar would be too expensive without slave labor, highlighting the unfairness of such a view.

The famous economist John Maynard Keynes once called Montesquieu "the greatest of your economists." He praised Montesquieu for his clear thinking and good sense.

Climate and Society

Montesquieu also had a theory about how climate might affect people and their societies. In The Spirit of Law, he suggested that the weather and environment could influence human nature.

He believed that people in very hot countries might be "too hot-tempered." Those in northern, cold countries might be "icy" or "stiff." He thought the moderate climate of France was ideal. This idea was common in his time. It shows how Montesquieu looked at many different factors, including the environment, to understand how societies develop.

Montesquieu's Main Books

- Lettres persanes (Persian Letters, 1721)

- Le Temple de Gnide (The Temple of Gnidos, a poem; 1725)

- Histoire véritable (True History, a tale; around 1723–1738)

- Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence (Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, 1734)

- Arsace et Isménie (Arsace and Isménie, a story; 1742)

- De l'esprit des lois ((On) The Spirit of Law, 1748)

- Défense de "L'Esprit des lois" (Defense of "The Spirit of Law", 1750)

- Essai sur le goût (Essay on Taste, published after he died in 1757)

- Mes Pensées (My Thoughts, his personal notes from 1720–1755)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Montesquieu para niños

In Spanish: Montesquieu para niños

- Environmental determinism

- Liberalism

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- List of political systems in France

- List of liberal theorists

- Napoleon

- Politics of France

- Jean-Baptiste de Secondat (1716–1796), his son

- U.S. Constitution, influences